The December 2019 election presented a clear choice to the British people. A Labour party mobilised on a scale not seen since the 1950s faced a Conservative party with limitless funds and unrivalled expertise in modern techniques of mass persuasion. Corbyn inspired young people with a programme that was an equal to the challenges facing the country. But his project failed nevertheless.

Millions were still caught up in the dreamworld of resentments and fantasies constructed by the billionaire press. Not only that, after the close election in 2017 the right and their media spent two years telling carefully identified audiences whatever they thought would best alienate them from Labour. Millions who stood to gain from a Labour victory came to believe that Corbyn was just another triangulating politician, a closet racist, or an out of touch metropolitan do-gooder. As a result the most authoritarian and incompetent administration in living memory secured a handsome majority after a campaign of idiotic lies and poisonous libels.

All the while elements in the Labour Party itself and supposedly moderate and liberal elites outside were working together to undermine Corbyn and his political project. In the words of Peter Mandelson their goal was nothing less than “to bring forward the end of his tenure in office”. A few months later those who had worked hardest behind the scenes to destroy Corbyn’s brand of social democracy were celebrating when their favoured candidate was installed as leader of the party.

There is only one lesson we should take from all this. We lack the democratic power we need to change Britain for the better. It is up to us to build that democratic power – in both the institutions of civil society and in the places where we live. And let’s be clear about what that means. It is about more than ‘electing the right people’ in an unreformed system, as the Corbyn project sought to do. Democratic power means ordinary people controlling material resources, creating consequences for disloyal elites, and building a shared understanding of politics. It means huge numbers of us learning how to govern ourselves.

From popular assemblies in our towns and cities to egalitarian control of funds in formally democratic membership organisations, we have a range of institutional mechanisms and collective forms with which to build this democratic power. We believe that only democratisation in this deep sense can unite those of us who want another, better world in sufficient numbers.

Democratic Places

Just as decisions at Westminster are dominated by economic elites, at a local level councils are often dominated by political cliques with close ties to the wealthy and without roots in the wider community. Councillors’ engagement with locals is more bins than big vision, which usually serves the profits of enormous commercial landlords, property developers and favoured contractors. Residents are treated more like customers than partners in running the area. There is a widespread, and often justified sense, that councils won’t put ordinary people’s interests first. A few local authorities have followed the lead of Preston City Council and pushed back against austerity by creating new partnerships with their communities and building new kinds of economic power. But too many are too content to make ‘hard choices’ and keep the community at bay.

The foundations of this order are weaker than they look. By both winning elections at a community level, and demanding power through building our own participatory processes, we can change local power dynamics. In Frome in Somerset, a group of determined locals won control of the town council. They opened up decision-making in significant and subtle ways. From allowing the public to sit around the same table as councillors at official meetings, to doing so much community engagement that decisions at ‘full council’ effectively rubber stamp a decision already made by a much wider group of people, they have transformed the idea of what a town council does, and have started many projects outsiders might describe as socialist.

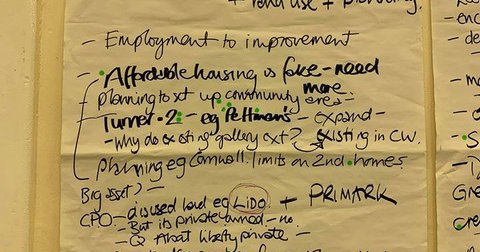

In Manchester, local campaigners have established citizen commissions to investigate issues they feel have been neglected by the Council – from poverty to the region’s top-down devolution deal. In Margate, an ad hoc community group organised a public meeting to discuss how £25m of central government regeneration money should be spent locally. This meeting, which took place in one of the most deprived wards in the UK, revealed almost unanimous support for the creation of public assets, as against subsidies for local economic elites.

What these ‘a-legal’ democratic processes show is that, when elected politicians no longer monopolise decision-making, ‘ordinary people’ quickly dispense with what is considered political common sense, and instead propose radical and progressive ideas. We don’t so much have to persuade people, as show how fiercely their favoured politicians oppose the changes they want. Wherever councils continue to act as though they know better than residents, radical democrats can run public events demonstrating how wrong they are, and publicise the results to an ever-widening circle of

citizens. In many places this could be the first step in building local movements powerful enough to force the hand of local politicians.

Each parish, town, district and city council presents us with an opportunity to build a parallel economic infrastructure with the power to fend off the worst of the Conservatives’ coming attacks on living standards. But only radical democracy will enable the majority of voters to understand what is happening – who is to blame, and who deserves gratitude. Without widespread participation the left’s efforts in local government, however heroic, will be depoliticised at best and appropriated at worst. The aim here is not a series of attempts by the relatively well-off to influence local decision-making. The aim is to model forms of collective decision-making that can then be integrated with the existing institutions of local government. Scarce resources that are currently spent talking at citizens would then be redirected to create opportunities for citizens and elected representatives to talk with one another as civic equals.

One of the best kept secrets of public life in the UK is the potential for democratic transformation that lies in the institutions of local government. Perhaps we don’t know enough to set out a complete blueprint for what we want. But we never will until we start. Besides, there are methods and institutional forms from here and around the world that can inform our approach. What’s certain is that we cannot wait for a national government to give us permission.

Democratic Bodies

Millions of us pay direct debits each month to clubs, unions and other, nominally democratic bodies. Millions more of us belong to organisations like Nationwide and the Coop that claim to be member-led. But we have little say in how these institutions are run. What if, instead of being presented with a ballot paper of people we haven’t heard of every year, we organised to take control of them with an explicit mandate to push decision-making and material control downwards? What if ordinary members then had the power and resources they needed to keep elected officials and bureaucrats under close supervision? What if taking turns to rule became normal in one institutional context after another?

Over more than a century the British working class created its own institutions to look after its collective interests. It set up trade unions, cooperatives, social clubs, its own political party. These all helped to bind together a thick social movement that weaved proletarian consciousness into everyday life. But thanks to economic restructuring, and ‘professionalisation’ of Labour and the unions, we have lost our connection with these organisations, which either withered away or fell to the control of a self-serving management elite. But these are our institutions, we can take them back if we work together.

Our trade unions have around £1 billion in annual turnover. The largest of them run surpluses in the tens of millions and have reserves in the hundreds of millions. Redirecting a tiny portion of this money to strategic projects such as popular, democratic media would make an enormous dent in the billionaire press, without putting any of members’ interests at risk. Communications budgets that are currently used to seek favourable coverage in media that are structurally opposed to working class interests could be put under direct, egalitarian control by members. Every member would choose which media operations to support, and be given opportunities to discuss their choice with other members. Over time more and more of us would gain first-hand experience of ‘that little smidgeon of power’ that Rupert Murdoch once described: the power to effect material change through control of communicative resources.

With six million members encouraged to tune in, and using networked organising to further build an audience, media supported by trade unionists could rapidly chip away at neoliberal common sense. Genuinely independent media could finally start to dismantle the credibility of the Daily Mail and the Telegraph in the minds of the people we need to win over. The BBC would start to come under pressure to stop repeating right-wing talking points. Millions of people could hold their own in debates in the pub (or local Facebook page) about the future of the furlough scheme, and why it certainly is affordable for as long as it’s needed.

Britain’s largest membership bodies have even more resources at their disposal. Radical democrats, united by a programme of radical democratisation, could organise to put their vast pools of idle money to use in ways that disrupt elite rule. Organisations like the National Trust, for example, could bring ordinary members into their governance structures in numbers sufficient to ensure that its policies reflected their preferences, rather than those of the establishment. Who knows, once reformed these bodies might mobilise in favour of action to address the climate crisis with a ferocity that is currently lacking. At the moment the leaders of these bodies often value ‘access’ to government far too highly, and overlook, or deliberately obscure, the enormous power a mass membership can wield.

Political parties sometimes exhibit the same problems that beset the rest of civil society. On the one hand we find an inert and poorly informed membership, on the other a small minority who hoard knowledge and power. This will not change until the few have developed a healthy fear of, and respect for, the many. And we should not fool ourselves into thinking that the necessary reforms are simple or self-evident. At the moment it is all too easy for members to be alienated from their interests. They have little time to dedicate to the minutiae of party administration and few means to do so. They are likely to be well-meaning amateurs in a world of clear-eyed and unflinching experts. And their opponents, who understand the stakes extremely well, have every reason to ensure that attempts to challenge them end in obscure failure.

Taking over and democratising a large organisation might sound too ambitious. But there’s no reason we can’t start smaller. If there’s a working mens, reform or liberal club in your town or neighbourhood, you and a few friends could take over the management committee and reform the structures so that passive members are brought into its decision-making structures. In this way co-operatively constituted clubs could support co-operative micro-breweries and other social enterprises in a small scale version of community wealth-building. Institutions that have become insular can once again become core to the human fabric of a place. Something as simple as a rule allowing any member to stop an elected councillor or MP from talking might start to establish a more healthy relationship between the public and the people who are meant to serve them.

The Prize

The immediate value of radical democratisation would be immense. Once we begin to work with others to shape our communities and shared institutions we no longer have to hand resources upwards to be controlled by a few privileged people. We can act in ways that privileged people find uncomfortable. Indeed, elected leaders can stop worrying about how to keep ‘their’ membership passive and uninformed. Instead they can concentrate on doing what they are told by people who know what they want, and have the knowledge, skills and confidence to help.

If anything the message radical democratisation sends to the British people would be even more important. Research by Common Cause has found that a large majority of the UK population are driven by ‘extrinsic’ values, that is, values like universalism, benevolence and compassion – all things that promote ‘prosocial behavior’. The problem is, everyone thinks that everyone else is motivated by money, power and status. Decades of right-wing propaganda have persuaded an ordinarily kind and thoughtful group of human beings that most of us are greedy hooligans. With the rise of mutual aid across every corner of the UK, there’s perhaps the glimmer of an awareness that we’ve been lied to. If we organise to act, and communicate the difference ordinary people can make when they take power, radical democratisation will finally begin to show the British people what they are made of.

4. Who Wants It?

So what should we take from the above? Basic accountability would be fine, but radical democracy would be better, and it’s more than possible. Instead of voting for the person who makes decisions about our communities, they can help us make those decisions together. Instead of paying officials to decide what’s best for us, members of a coop or a union can decide for themselves.

Citizens for a Democratic Society (CDS) aims to be a coordinating body and information resource for people who want to create a deeper democracy in Britain before it is too late. Now that we’ve tried everything else, we’ve accepted, more or less reluctantly, that our only chance is each other.

We want to start taking back control of places and spaces that are currently run by unaccountable elites and their bureaucratic allies. If you live in a place where power seems distant and hostile, we’d like to talk with you. If you are a member of an organisation that is meant to be democratic but tells you nothing and obeys you even less, we’d like to talk with you. If you are already working to make democracy a fact of life somewhere, we’d like to talk with you. If you’ve already built an institutional space where members exercise real control, we’d like to talk with you.

If you have practical skills and experiences to share, we’d like to talk with you.

You get the point. We’d like to talk. More than that, we’d like to start putting together a networked group in a rolling campaign to democratise Britain from the ground up. We don’t have foundation funding or rich backers. If what we propose strikes a chord then we will build a membership organisation that is a worked example of the radical democracy we are seeking to create, in which the burdens – and satisfactions – of power are shared equally.

But that’s for the future. Right now we’re about making ourselves useful. Sometimes we will be able to put activists in touch with people who have tried something similar, or suggest tactics that have been successful elsewhere. Sometimes we will be able to provide a point of contact for people with a shared analysis of their situation, and a compatible agenda for change. In many contexts we will be learning from others. For example, although some of us are Labour members, we are well aware that others know far more about that Party’s internal structures, and how they might be wrestled away from the hands of the few.

The key institution in a fully realised democracy is the assembly – a space where citizens meet as equals and develop a plan of action that commands general consent. If we want a democracy then, one by one and in our own time, we are going to have to assemble. CDS is somewhere some of us can start working together, and some of us can continue work already begun.

Citizens for a Democratic Society aims to transform society through mass participation and public control. We help each other to reclaim our member organisations and places where we live from unaccountable elites and their bureaucratic allies. In the piece below we set out what we think the current moment tells us, and why we think radical democratisation is the unifying project to finally put the people back in control. Get in touch if you’d like to join in or find out more, and we’ll be in touch.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.