Union power is ebbing in the private sector, with organized labor at the lowest point it has been in over 80 years. Vast, powerful employers like Walmart, Amazon, Home Depot, and FedEx are entirely nonunion. But in 1933, at the bottom of the Great Depression, a much more difficult task faced the labor movement, as prominent trade unionists were routinely beaten and killed, and no legal framework for unions even existed. What would it take to spark a revival, and what is the history new labor organizers, activists, and members could learn from to be a part of it?

One of the most curious publishing successes of the second half of the 20th century is now in a new reprinting, a resuscitation of the 1955 book “Labor’s Untold Story: The Adventure Story of the Battles, Betrayals and Victories of American Working Men and Women,” originally written by Richard O. Boyer, a freelance contributor to the New Yorker, and Herbert M. Morais, a lapsed academic and, later, a union staffer.

It’s a cinematic tale, but one that mainstream book publishers have largely avoided, leaving the vacuum to be filled by labor itself — and specifically by the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America, known as UE, one of the more eclectic and creative unions in the labor ecosystem.

An antidote to labor denial, the book details the story of violence, heart-wrenching defeat, and eventual mass victory of American labor, paying particular attention to the formation and rise of the Congress of Industrial Organizations from 1936 to 1945 (now the CIO in AFL-CIO) in an accessible way.

Book cover: United Electrical Workers

For unions in America, a fundamental problem is apathy. Members do not want to get involved, and a component of this is that there is not a sense of what the union stands for and what being in a union means. It may not be a coincidence that the book is published by the UE, a union known for its ideologically motivated membership. Were other unions besides the UE to encourage mass readership of “Labor’s Untold Story,” perhaps they could begin to address this problem of apathy and begin to build out their internal organization. Indeed, the UE, whose motto is “The Members Run This Union,” has been at the forefront of some of the most innovative struggles in modern American labor, despite its small size of 35,000 members. (Conservative unions nearly drove the UE out of existence during the post-World War II Red Scare for the unions’ refusal to expel communists.)

The UE led the Republic Windows and Doors factory occupation in 2008 and 2009 and has had a steady stream of big union wins in recent years as the power of labor recedes. Indeed, during the pandemic, the UE organized 380 new workers, pitifully making it the eighth-largest organizer of workers of America’s unions, despite the vastly larger size of other unions. Recently, the UE has partnered with the Democratic Socialists of America on an ambitious pandemic organizing project, the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee. The UE has also attracted notoriety for the low salaries of its national officers: Tied to the salaries of production workers at General Electric, they are capped at about $63,000 annually. By contrast, the president of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers made $477,000 last year.

“Labor’s Untold Story” begins with the Civil War, when many of the people involved in the country’s nascent labor movement enlisted in the Union Army after slaveholders attacked Fort Sumter. Entire trade union locals dissolved, seeing the massive threat that slavery presented to the interests of free labor. In 1857, the Supreme Court had ruled in Dred Scott v. Sandford that slavery was effectively legal in every state. Boyer and Morais recall that noted abolitionist Wendell Phillips was deeply pessimistic about what the future held, writing around 1856, “The government has fallen into the hands of the Slave Power completely. So far as national politics are concerned we are beaten — there’s no hope. We shall have Cuba in a year or two, Mexico in five. … The future seems to unfold a vast slave empire united with Brazil. I hope I may be a false prophet but the sky never was so dark.”

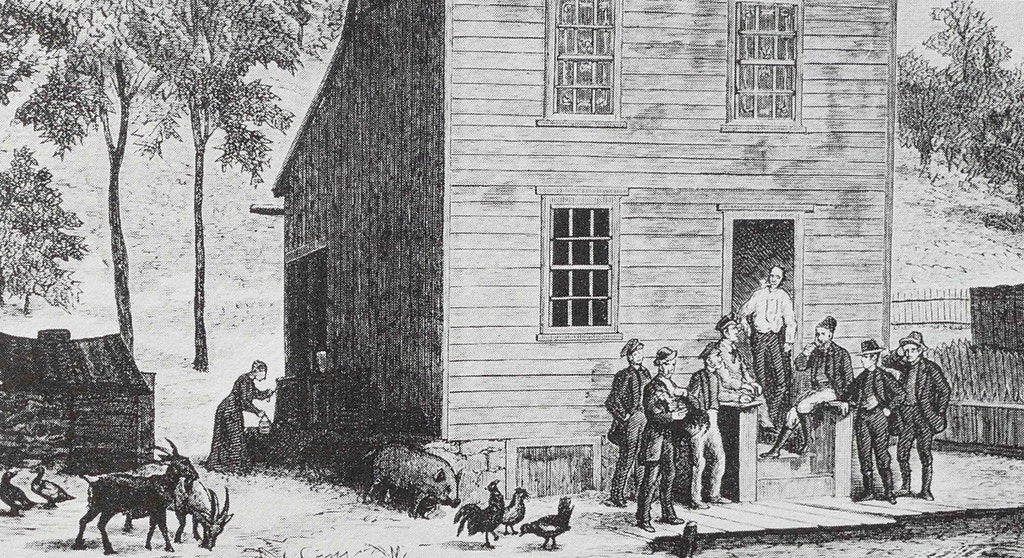

Photo: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Less than a decade later, slavery and the slave power were smashed, and people born enslaved were elected to office throughout the South on ambitious land reform platforms — and the first national labor organization, the National Labor Union, was founded with a leader, William Sylvis, committed to uniting Black and white, male and female, to fight for basic economic rights. While the NLU, despite at some points commanding hundreds of thousands of members, collapsed in 1873 in the face of economic depression, Sylvis and the NLU created the framework that exists today: organizations of workers on the basis of common interest, without regard to their background.

One of those early organizations was the Workingmen’s Benevolent Association of Schuylkill County, or the Molly Maguires, a fictitious name developed by anthracite coal barons in Pennsylvania’s Schuylkill Valley to tar the Irish leaders of the incipient miners union. The Benevolent Association was founded in 1868, with a core membership in the Ancient Order of Hibernians, an old Irish fraternity. The next year, on September 6, 1869, “The whistle stop atop the colliery at the Avondale Mine in Pennsylvania’s Luzerne County sent out the sharp, repeated blasts that told of an accident. … Great columns of smoke and fire were billowing out of the only shaft, the only entrance or exit, and the women and children knew that their husbands and fathers were dead men unless they could blast their way to life by forcing a second exit,” which they were unable to do. All 179 were eventually brought out of the mine dead two days later, all because the mine owners decided not to take the safety precaution of having an emergency exit. John Siney, the head of the Benevolent Association, said to the other miners gathered in a crowd: “If you must die with your boots on, die for your families, your home, your country, but do not longer consent to die like rats in a trap for those who have no more interest in you than the pick you dig with.” Thousands of miners joined that day. Of the 22,000 working in the Schuylkill mines, 5,500 were children, working some of the most dangerous jobs.

As the union grew, a progressive caucus of young miners affiliated with the AOH began to push for “straight-shooting” trade unionism. Those miners would be the ones who their adversary, the boss Franklin Benjamin Gowen, would tar with the Molly Maguire label and eventually have hanged. As the Panic of 1873 set in, Gowen faced extreme pressure to significantly lower miners’ wages, which led to a six-month strike beginning on January 1, 1875. It failed, but the progressive caucus in the union had not given up and was still fighting back inside the mines. Gowen resolved to crush the union once and for all. Alternating between charging them with communism or terrorism, Gowen waged an all-out public relations campaign against the Molly Maguires and framed them for murder using the Pinkerton Detective Agency, with a spy alleging that the leaders had committed various murders. Gowen ensured that he himself was appointed special prosecutor, and the 10 leaders were hanged on June 21, 1877.

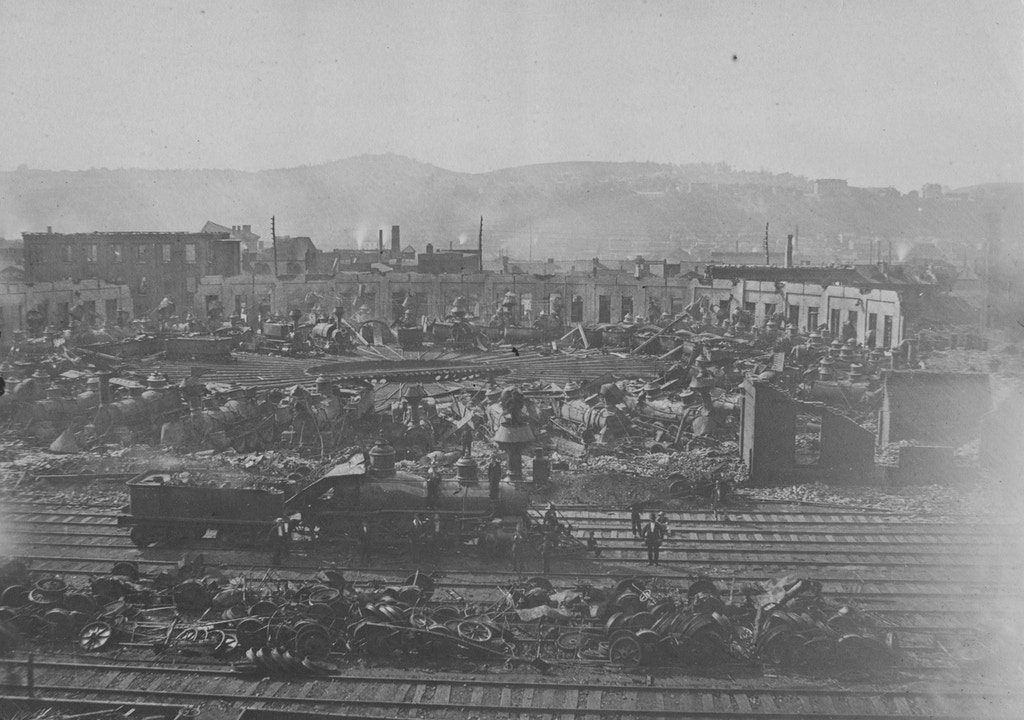

But as soon as the miners were hanged, labor roared back with the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Following another wage cut, over 100,000 struck nationwide. That strike too was crushed. So too was the Knights of Labor, so too was the Industrial Workers of the World — fleeting national worker organizations accompanied by vicious state terror.

Photo: Kean Collection/Archive Photos/Getty Images

It was not until the harrowing poverty of the Great Depression that “the triumph that the Molly Maguires had never found … was about to arrive, and it was sweet when it came at last.” Global production had decreased by 42 percent and world trade by 65 percent. The Depression got worse year after year from 1929 to 1933. While President Franklin D. Roosevelt initially got labor union rights passed in 1933, the right-wing Supreme Court struck it down. In response, employers began spending $80 million annually on spies to prevent unionization. The defunct Ku Klux Klan was relaunched, with its primary target union organizers, as well as the Black Legion, a Northern version with a fascist tinge.

Nearly 100 years of struggle culminated in the rise of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, which split from the conservative American Federation of Labor in 1936: “The CIO was the leaping flame suddenly blazing bright in the long night of the open shop.”

Boyer and Morais write, “By 1934 labor solidarity, ‘an injury to one is an injury to all,’ had soared to a general acceptance by local unions the country over. When one union’s picket lines were attacked by police all unions in a given locality threatened general strike,” which occurred in Minneapolis and in San Francisco that year. Roosevelt, though appalled by general strikes, used them to his advantage. After the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, a Roosevelt aide said, “The concept may dawn even on the [Supreme] Court, that a government labor board is in some measure a necessary alternative to a general labor war.” The NLRA was upheld, and the following year the CIO was founded, organizing millions of workers in the automotive (prompted by the Flint sit-down strike), steel, electronics, and rubber industries, and nearly every other industry, as well — unions that still exist today.

Union density in the private sector is now as low as it has been since 1937. Unions have lost much of the militancy and will that characterized the early days, leading its members to become disconnected from the broader project of economic rights for all. Only by knowing our country’s true history — the history of the people that built it — can stronger unions be built by informed, engaged, and active members.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.