As Covid-19 tore through the United States in the spring, a senior official in the Trump administration quietly reinforced a set of guidelines that prevented journalists from getting inside all but a handful of hospitals at the front line of the pandemic. The guidelines, citing the medical privacy law known as HIPAA, suggested a nearly impossible standard: Before letting journalists inside Covid-19 wards, hospitals needed prior permission from not only the specific patients the journalists would interview, but also other patients whose names or identities would be accessible.

The onerous guidelines were issued on May 5 by Roger Severino, who worked at the conservative Heritage Foundation before Donald Trump appointed him to direct the Office for Civil Rights at the Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS. The guidelines made it extremely difficult for hospitals to give photographers the opportunity to collect visual evidence of the pandemic’s severity. By tightening the circulation of disturbing images, the guidelines fulfilled, intentionally or not, a key Trump administration goal: keeping public attention away from the death toll, which has surpassed 300,000 souls.

“The last thing hospital patients need to worry about during the Covid-19 crisis is a film crew walking around their bed shooting B-roll,” Severino said dismissively in a short press release accompanying the guidelines.

Severino speaks at a news conference in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 18, 2018.

Photo: Aaron P. Bernstein/Getty Images

In the pandemic’s early days, when hospitals were first inundated with media requests, the prevailing HIPAA guidelines were quite restrictive, even on matters that had nothing to do with media access. Those guidelines predated the Trump administration and were not written for a pandemic. But the scale of the Covid-19 crisis quickly forced the Trump administration to loosen a wide range of privacy restrictions on medical providers — except, as it turned out, the ones that kept Americans from viscerally seeing the ailing and the dying.

For instance, HHS allowed hospitals to share Covid-19 information with first responders and with organizations involved in Covid-19 testing. Hospitals were told that they would not face sanctions for sharing information with the families or friends of Covid-19 patients. Doctors were freed to discuss or transfer patient information with technologies that were not secure, such as email, FaceTime, and Skype. As it relaxed these restrictions, the agency said that medical providers would not be punished for breaches of patient confidentiality if they acted in good faith during the pandemic.

The government’s permissiveness did not extend to journalists. The media guidelines announced by Severino in May reinforced HIPAA’s restrictions and warned hospitals that violations could bring fines in the millions of dollars. The announcement was not reported by general-interest publications, but news outlets for the health care industry noticed what had happened. The headline of one of those industry stories was blunt: “Patient Privacy Prevails Over Covid-19 Media Coverage.”

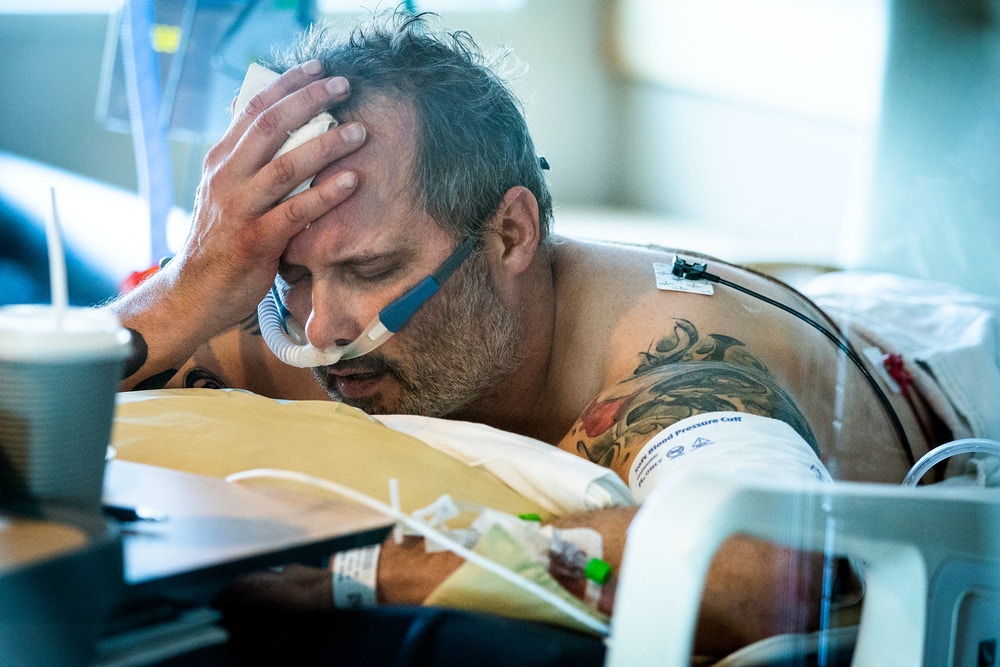

Severino’s guidance, little known outside the health care industry, may help solve one of the mysteries of the pandemic: Why have Americans seen relatively little imagery of people suffering from Covid-19? While there is a long-running debate over the influence of disturbing images of death and dying — whether they actually move public opinion — the relative paucity of videos and photographs of the pandemic’s victims might help explain why Covid-19 skepticism has thrived as the death toll in America reaches the level of a 9/11 every day.

“For society to respond in ways commensurate with the importance of this pandemic, we have to see it,” wrote art historian Sarah Elizabeth Lewis. “For us to be transformed by it, it has to penetrate our hearts as well as our minds. Images force us to contend with the unspeakable. They help humanize clinical statistics, to make them comprehensible.”

Photo: John Moore/Getty Images

From the moment Covid-19 took hold, journalists in the United States experienced immense difficulty getting access to what amounts to ground zero of the emergency. This was not because they were not trying — they deluged hospitals with requests to document what was happening. Nor was it because doctors and nurses resisted — they clamored for more attention to the agonies endured by their patients. With infrequent exceptions, hospitals said no to the requests from journalists, often without explanation.

Lucas Jackson, a senior photographer for Reuters, recalls that at the start of the pandemic in March, he worked with a team at Reuters that called nearly every hospital and trauma ward in New York City. They created a spreadsheet of the hospitals and whether they had been contacted and what their response was. Only a few responded, and none granted access, even though Reuters offered Guantánamo levels of control to hospital staff, agreeing to get releases from patients and allowing hospital staff to look at all photographs to make sure no names or identities were disclosed. “If that’s what it takes, we were willing to do it,” Jackson told The Intercept.

“Photography has played such a key role in the civil rights movement, in ending the Vietnam War, and any number of key moments in American history — and it just seems missing in action on this crisis.”

Michael Kamber, a former war photographer who directs the Bronx Documentary Center in New York City, recalls security guards shooing him off the sidewalks in front of Lincoln Medical Center. “This is the greatest loss of life on the American continent in such a concentrated time, and we’re seeing almost no images that really convey the devastation and the death,” Kamber said. “Photography has played such a key role in the civil rights movement, in ending the Vietnam War, and any number of key moments in American history — and it just seems missing in action on this crisis.”

Kamber, like other photographers, accepts that safety and privacy concerns need to be upheld, but he believes that those concerns are used as excuses for the repression of journalism that is manifestly in the public interest. In the cases in which hospitals have allowed journalists inside during the pandemic, there have been no privacy breaches — which proves that reporters can work at the medical front line without violating patient privacy. “The government and nearly all health care facilities have banded together in the name of protecting the privacy of the sick and have done an excellent job of keeping photographers as far away from the grief and devastation as possible,” Kamber said.

There have been exceptions, of course. John Moore, an award-winning photographer for Getty Images, got inside a Connecticut hospital in the early days of the pandemic. A contact with connections to the hospital vouched for Moore, removing the obstacles that were keeping others out. Even so, Moore had just one visit to the intensive care unit, working in a hurry with a communications official carrying a stack of releases that everyone he came into contact with had to sign. Moore did not take pictures of patients’ faces. “We established ground rules ahead of time, and I stuck to those,” he said.

Getty Images is a major photo agency that has worked hard to get its photographers into hospitals, with only rare success. “For every thousand calls or emails, you maybe get three yeses,” said Sandy Ciric, the agency’s director of photography. “Sometimes we even had the CEO say, ‘This is great, yes, we want coverage,’ and then someone tells them no and they change their mind.”

The exceptions demonstrate that not all the blame can be placed on the government. There is enough wiggle room in the regulations for determined hospitals to let journalists inside and trust them to follow the rules. Journalists who spoke with The Intercept noted a similarity to embeds with the U.S. military: Just as embedded war reporters were privy to sensitive information that they were trusted to keep to themselves, journalists in hospitals can be counted on to not publish patient information that they are not supposed to publish.

A photographer who got access to several hospitals in the early months of the pandemic expressed quiet fury that most medical facilities in the country chose to keep their doors closed. “I was not happy that I had a scoop,” said the photographer, who asked that their name not be used in order to protect their ability and their employer’s ability to continue to work inside hospitals. “I was not happy that I had exclusive access. I felt that all my colleagues should have had the same access I had. … The dearth of images of death and dying directly contributed to the disinformation [about Covid-19] and the ongoing disbelief in our country, full stop. And the hospitals have to answer for that. The hospitals bear some responsibility.”

Photo: Shannon Stapleton/Reuters

The war metaphor sheds light on why 300,000 coronavirus deaths have elicited a shallower national response than the loss of life in previous catastrophes. Domestic opposition to the war in Vietnam was shaped by imagery of U.S. soldiers as well as Vietnamese civilians in agonizing moments of injury or death. Americans were horrified to see the true face of war. Having learned its lesson, the U.S. government suppressed imagery of American casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan: The embed program aimed at preventing journalists from roaming around battlefields on their own, taking pictures of whatever they wanted.

Eerily, the embed guidelines used by the Pentagon included a prior-consent clause similar to what HIPAA, or the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, demands. The guidelines prohibited war journalists from publishing pictures or videos of wounded soldiers unless they had prior written permission from the soldiers (a practical impossibility on the battlefield): “Names, video, identifiable written/oral descriptions or identifiable photographs of wounded service members will not be released without service member’s prior written consent.” The guidelines also enforced a ban on photography of the dead: “Images clearly identifying individuals ‘killed in action’ will not be released.”

The unifying principle between repressing photography of a war and photography of a pandemic is that a population that cannot see human carnage will not object as strongly to its perpetuation and will not care as much about the incompetence that brought it on. Hospitals and nursing homes may not have the mendacious intent of the U.S. military, but their actions have a similar effect of making it nearly impossible for ordinary Americans to be confronted with visual evidence of the true cost of the calamity that’s unfolding.

The Intercept reached out to a number of hospitals to ask about their media polices, including Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles, Mount Sinai in New York City, and Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. The only one that responded was Massachusetts General in Boston, which provided the following statement:

MGH has been restricting outside photographers from working in areas of the hospital where staff care for COVID patients. This is for both for the privacy of our patients and also their safety and that of our staff. Throughout the pandemic, the hospital has taken careful steps to minimize the amount of people coming to campus to ensure that only those essential for patient care and hospital operations are working in the building. While we recognize the importance of telling the story of how this pandemic has affected our patients and staff, our top priorities must always be privacy and safety. Our team has taken additional steps to make our experts, caregivers and consenting patients available to journalists remotely, as well as images and videos captured by our staff photographers.

As the daily death toll reaches shocking new highs, there continues to be relatively little photography of patients in hospitals. The Intercept reviewed the front pages of the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times for the past month and found no photos of hospital patients on all but a few days. When there is photography from inside hospitals, it is almost always of doctors and nurses. The pandemic certainly gets its share of visual coverage, but the pictures tend to be surrogates of suffering, such as people wearing masks as they wait for Covid-19 tests or go about their daily routines. Because it doesn’t happen often, when a powerful photo from inside a hospital happens to emerge — such as Go Nakamura’s photo of a doctor embracing a Covid-19 patient last month — it gets an enormous amount of attention.

Photo: Go Nakamura/Getty Images

“Events on this scale are understood through abstractions, which is necessary and likely helpful in terms of psychological defenses, but also results in a disconnect between people who experience it firsthand, and those who do not,” noted Dr. Elizabeth May, a psychiatry resident at a hospital in New York City. “As a physician, I wish that those close to me could really picture and see what I have seen, that I could know that they have seen this, and not feel like I need to protect their abstractions when what I really need is their support and empathy.”

Willingly or not, some hospitals have turned themselves into apparatuses of silence — and staff inside them are upset.

In April, when the first surge of the pandemic decimated New York City, a nurse at Lincoln Hospital shared video footage of herself and other staff describing the difficulty of treating Covid-19 patients without adequate protective gear or lifesaving supplies. The video was published by The Intercept, and shortly afterward, the nurse, Lillian Udel, was informed by the hospital that she was being investigated for HIPAA violations. That prompted another nurse at the hospital, Kelley Cabrera, to speak out. “HIPAA is kind of being used to gag people,” she told The Intercept’s Akela Lacy. “We’re all experiencing the most difficult working conditions we’ve ever faced. And everybody who is speaking out is doing so to advocate for patients, ultimately. It looks like hospital administrations tend to run to HIPAA for their protection, not so much patient protection.”

May, the psychiatry resident, noted how some hospitals, even in a pandemic, are reluctant to show what happens behind their doors.

“Hospitals, as businesses, as profit-driven entities, do not want to be associated with death and suffering — it is very off-brand for them, I think,” said May. “So emerges an unfortunate dovetailing of HIPAA as a safeguard for civil rights and HIPAA as a vehicle for hiding off-brand aspects of medicine. … As a psychiatrist, I find myself thinking about shame and what role institutional shame has to play in the hiding of death and suffering.”

Dr. Elisabeth Poorman, a physician in Seattle, was particularly blunt on social media. “Americans do not respond to statistics,” she wrote on Twitter in June. “They respond to stories. Every hospital needs to let cameras in and show what dying of Covid looks like. Instead, PR depts silence us.” Responding to a commenter who said HIPAA was silencing the hospitals, Poorman shot back, “No, HIPAA is the excuse.” Earlier this month she told The Intercept, “I don’t really see things changing, because people don’t want to think creatively about this.”

Photo: Leila Navidi/Star Tribune/Getty Images

When HIPAA was passed in 1996, the law did not include media guidelines. That changed after hospitals, seeking to increase their profiles and their revenues, opened their doors to reality TV shows. In 2012, one of those shows, “NY Med,” which starred Dr. Mehmet Oz, broadcasted an episode that featured a blurred-out patient in the emergency room who had been hit by a sanitation truck. The patient died, and when the episode aired, his widow happened to be watching and recognized her late husband’s voice. She was shocked. Neither she nor anyone in her family had given permission for her husband’s last moments to be filmed.

Four years later, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital agreed to pay a $2.2 million fine. HHS also announced strict new guidelines that required, before journalists could enter any patient area, “prior written authorization from each individual who is or will be in the area or whose PHI [protected health information] otherwise will be accessible to the media.” These guidelines in 2016 spelled the end of reality TV shows about hospitals and unfortunately turned them into no-go zones for reporters who, unlike reality TV crews, could be trusted to behave responsibly.

Severino, choosing to reinforce rather than relax the 2016 guidelines, was unequivocal in May. “The Covid-19 public health emergency does not alter the HIPAA Privacy Rule’s existing restrictions on disclosures of protected health information (PHI) to the media,” his guidelines stated. “As explained in prior guidance, HIPAA does not permit covered health care providers to give the media, including film crews, access to any areas of their facilities where patients’ PHI will be accessible in any form (e.g. written, electronic, oral, or other visual or audio form) without first obtaining a written HIPAA authorization form from each patient whose PHI would be accessible to the media.” (The italics are in Severino’s guidance.)

Severino declined an interview request from The Intercept, but his office released a short statement in his name that said his decision to relax some HIPAA guidelines “can help save lives during the pandemic.” His statement justified the reinforced media restrictions by saying that “hospitals allowing camera crews to film Covid-19 patients in distress without their permission is a breach of trust that violates patients’ privacy rights.” But this ignores the fact that the lessons of 2012 have been learned; nobody is proposing to broadcast videos or photos of non-consenting patients. In essence, Severino is all but barring journalists from hospitals because he says they will do something that they pledge they will not do and that hospitals would not permit them to do.

Adam Greene, an expert on HIPAA and a partner at the law firm Davis Wright Tremaine, said it comes down to the amount of legal risk a hospital is willing to assume and the amount of time it is willing to devote to figuring that out. A hospital has to wade through a lot of regulatory questions before deciding to let a journalist inside, and that means tapping into legal resources that might be scarce or expensive. And if a decision is made to grant access, there’s always a chance that something could go wrong and a privacy breach could happen. “When you look at the incentives for hospitals, it is much easier to decline the request and avoid any risk of penalty,” Greene said. “There is not much in it for them to spend the time and resources to navigate HIPAA to find a way to do this.”

This post was originally published on Radio Free.