Who needs the arrow of time, anyway? Roman Krznaric, an author and philosopher, is in search of unconventional ways of thinking about time, ones that aren’t tied directly to the clocks ticking all around us. In one exercise, he imagines his young daughter as a 90-year-old, cradling her first great-granddaughter in her arms.

“I look at her face, her old face, and I walk over to the window and look at the world outside, and see what kind of world that is,” he said. “I think of my daughter, or her great-grandchild, living well into the 22nd century — a time which is not science fiction, but an intimate family fact.”

It’s a sobering experiment for Krznaric, who, like a lot of us, has a “pretty dark” vision of the future. But most people don’t lose sleep over the fate of people who aren’t alive yet. More pressing concerns — the global pandemic, for example — have lodged themselves into our anxious brainspaces. The people of the future are merely hazy abstractions. But billions of real people will likely be born in the coming centuries, and depending on what we do next, they might be very disappointed with us. “Empathising with future generations may be one of the greatest of all moral challenges,” Krznaric writes in his recent book, The Good Ancestor: A Radical Prescription for Long-Term Thinking.

A broad, loose movement offering a new way of thinking about time has emerged in the last decade or so. Its goal is to preserve the Earth for its future inhabitants. Krznaric calls this a “time rebellion” in The Good Ancestor. These “time rebels” include the plaintiffs of youth climate lawsuits, who demand legal rights to a stable climate; the global climate strike movement founded by Swedish activist Greta Thunberg, which inspired millions of young people to skip class to call for climate action in the streets; and various artists, economists, and entrepreneurs who embrace “deep time” — the concept of expanding our temporal imagination to encompass geologic and cosmic timescales, from the fossil fuel record to the unfathomable expanse of the distant future.

Deep time is an antidote to the shortsightedness that has made governments so reluctant to act boldly to address the climate crisis. After all, the worst effects of our overheating planet will occur in the future, not the present. In his book, Krznaric looks to indigenous traditions, artistic projects, and new philosophies that seek to overcome this empathy barrier and fold the future into present concerns. One way to do this is by prompting people to think about the legacies they will leave, as Krznaric did when he imagined his daughter as a nonagenarian.

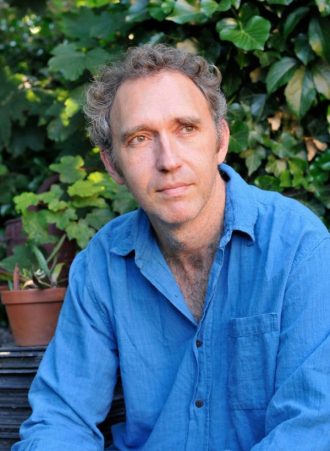

Roman Krznaric. Credit: Kate Raworth

Roman Krznaric. Credit: Kate Raworth

“What I’ve found is that the language of legacy seems to motivate people across different social realms with different backgrounds,” he said. (A small study from 2015 found that prompting people to think about how they’ll be remembered made them more likely to support personal and political action to cut carbon emissions.)

Krznaric has been interested in these questions for more than a decade. In a 2008 report, he argued that empathy is the most powerful tool we have to motivate people to take action on the climate crisis, an idea echoed in his 2014 book Empathy: Why It Matters, and How to Get It.

As Jamil Zaki, a professor of psychology at Stanford, writes in The War on Kindness, empathy is not a fixed trait: It’s a muscle that can be stretched and strengthened. With the new year just days away, it’s a good time to reflect on your legacy and how to be kinder to Earth’s inhabitants-to-be. If you want to try to be a better ancestor in 2021, here are a few ideas from Krznaric’s new book. “The path of the good ancestor lies before us,” he writes. “It is our choice whether or not to take it.”

Think about the seventh generation

Imagine if every time a politician made a decision, they considered what it would mean for the well-being of people who will live 200 years from now, rather than worrying about what it’ll take to win the next election. It’s contrary to a lot of decision-making in the United States, but this kind of long-term thinking is a tradition in many indigenous cultures around the world, Krznaric writes. The Māori — the indigenous Polynesian people of New Zealand — have a concept called whakapapa (akin to “genealogy”), an expression describing a long, unbroken chain of humanity that connects the deceased, the living, and the yet-to-be-born.

Native cultures are full of cautionary tales about the long-term consequences of taking too much, writes Robin Wall Kimmerer, a biologist and a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, in the book Braiding Sweetgrass. These principles — called the Honorable Harvest — “govern our taking, shape our relationships with the natural world, and rein in our tendency to consume — that the world might be as rich for the seventh generation as it is for our own,” Kimmerer writes.

In the last couple of decades, “seventh-generation thinking” has been adopted in sustainability circles. One of the goals of the global youth organization Earth Guardians is to “protect our planet and its people for the next seven generations.” In a 2008 speech, the Nobel Prize-winning economist Elinor Ostrom raised the question of how to preserve resources for the future, saying, “I think we should all reinstate in our mind the seven-generation rule.” You might have even seen a nod to this idea in the dish soap aisle: The Vermont-based cleaning product company Seventh Generation was founded on this same principle.

Pretend you’re living in 2060

The idea of the seventh generation also inspired a Japanese political movement called “Future Design.” From small towns like Yahaba to major cities like Kyoto, Japanese cities have instituted an unusual type of city-planning meeting. One group of citizens at the meeting advocates for current residents, while another group dons special ceremonial robes and conceives itself as “future residents” from 2060. Studies have shown that these future residents advocate for more transformative changes in urban planning, especially around health and environmental action.

Ultimately, Krznaric writes, the movement wants to establish a “Ministry of the Future” for the central government in addition to local ones. It’s a growing trend: Over the past 30 years, Finland, Hungary, Malta, Tunisia, Sweden, Wales, and the United Arab Emirates have all created positions, committees, councils, or commissions that advocate for future generations’ interests.

Give a gift to future generations

Six years ago, Scottish artist Katie Paterson created the Future Library, a century-long art project. Each year, a famous writer (the first two were Margaret Atwood and David Mitchell) donates a new work to the project — one that no one else has ever read. At the end of the project, in 2114, the 100 books will be printed on paper from a forest outside Oslo that’s been planted for this express purpose, to be enjoyed by the readers of the 22nd century.

Another project, the website DearTomorrow, allows you to write a letter to someone of your choosing — your child, perhaps, or your future self — to be delivered in the year 2050. The project was started by Kubit and Trisha Shrum, two alums of the Grist 50. The founders say that DearTomorrow is meant to close the gap between the far-off years referenced in climate reports (2050 is a common one) and make a personal connection to the future.

Krznaric says that an “intergenerational Golden Rule” drives these kinds of projects: a “basic empathic principle” that we should treat others as we’d want to be treated, including people who might be distant from us in space and time.

“When you think about the legacies we’ve inherited from the past, some of those are very positive legacies,” Krznaric said. “We are the beneficiaries of the people who planted the first seeds in Mesopotamia 10,000 years ago, who built the cities we live in, and who made the medical discoveries we benefit from. But we also are the inheritors of colonialism, slavery, and racism…. So do we want to pass on that stuff as well? No! Let’s pass on a different legacy to the next generation.”

This post was originally published on Radio Free.