In the last days of December, as the president played golf while ignoring both the coronavirus pandemic and the bombing of a U.S. city on Christmas morning, federal prosecutors were working overtime to grant him a parting gift in the name of law and order. After 10 executions in five months, the Department of Justice was planning one last round of killings in the federal death chamber. The executions would bring Donald Trump’s tally to 13, more than any president since Franklin Roosevelt.

Never mind that the last two men slated to die, Corey Johnson and Dustin Higgs, had recently been diagnosed with Covid-19. Both had symptoms of the virus for days before they tested positive at the U.S. penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana. Higgs has a long history of asthma, heart problems, and hypertension. Johnson has exhibited evidence of lung damage, according to his attorneys. But this has not deterred the Justice Department from pushing forward. On December 27, federal prosecutors informed a U.S. district judge that, although neither man had been retested and both still had symptoms, they had been “medically cleared from isolation status.” In other words, they had recovered for the purpose of execution.

Higgs and Johnson were not the only ones to get sick. The virus aggressively spread on federal death row after the back-to-back executions of Brandon Bernard and Alfred Bourgeois on December 10 and 11. At least 14 men had tested positive as of December 21, according to the New York Times, though the figure has grown much higher. One source with close ties to death row told The Intercept last week that the real number is “at least 30” — 60 percent of the total condemned population in Terre Haute.

There’s good reason to believe that Trump’s execution spree is responsible for the outbreak. Although cases were climbing at the penitentiary before the first killings in July, many warned that the federal executions could become superspreader events. The local newspaper called for a delay in light of the pandemic. Victims’ families protested that traveling to Terre Haute could put them at risk. On the eve of the first execution, news broke that a Bureau of Prisons staffer involved in preparations had tested positive. Nevertheless, the killings moved forward.

As autumn brought a surge in Covid-19 cases across the country, more people connected to the executions began to test positive. In November, lawyers for Lisa Montgomery, the only woman under a federal death sentence, became sick after visiting their client at FMC Carswell, a Texas medical facility for women in BOP custody. A few weeks later, Yusuf Ahmed Nur, the spiritual adviser to Orlando Hall, the eighth man to be executed, tested positive after accompanying him in the death chamber. Shortly afterward, in response to a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union, the Bureau of Prisons revealed that eight of approximately 40 members of the execution team had tested positive too. More recently the BOP admitted that it has failed to conduct contact tracing for fear of revealing the identities of those carrying out executions.

Although the return of federal executions after a 17-year hiatus refocused attention onto Terre Haute, the Covid-19 outbreak there mirrors death rows all over the country. Cases were documented from Arizona to Tennessee to California, where the virus proved especially deadly. As the year came to a close, the number of known Covid-19 deaths on state death rows stood at 17 — equal to the total number of executions carried out all year in the United States. The most recent came on December 28, when Romell Broom, who famously survived a botched execution attempt in 2009, died on Ohio’s death row at the age of 64; his name was placed on the corrections department’s “Covid probable list,” meaning he likely died from coronavirus complications.

People on death row represent a small fraction of the Covid-19 crisis in the country’s prisons and jails; an estimated 275,000 incarcerated people have contracted the virus in the United States and at least 1,700 people have died in custody. Some experts and advocates argue that, with capital punishment on the decline, the real “death penalty” is the lethal medical neglect that comes with mass incarceration. Yet the impact of the virus also speaks volumes about a policy that, by its own metrics, has been a failure since the start of the so-called modern death penalty era.

Along with its arbitrariness, racial bias, and track record of condemning the innocent, the American death penalty is increasingly defined not by executions but by the number of people who spend decades languishing in extreme isolation on death row, only to die of disease or old age. Broom’s death in Ohio was preceded by that of 79-year-old James Frazier, the oldest man on the state’s death row. In California, which has carried out a total of 13 executions since the death penalty’s return in 1978, 13 condemned people died of the virus in 2020. One man had been on death row since 1986.

If there is any silver lining to Trump’s execution spree, it is that it has reinvigorated momentum against the death penalty. In December, Massachusetts Rep. Ayanna Pressley, who introduced legislation to end the federal death penalty last year, sent a letter to President-elect Joe Biden asking him to act on his newfound opposition to capital punishment. “With a stroke of your pen, you can stop all federal executions, prohibit United States attorneys from seeking the death penalty, dismantle death row at FCC Terre Haute, and call for the resentencing of people who are currently sentenced to death,” she wrote. “Each of these elements are critical to help prevent greater harm and further loss of life.”

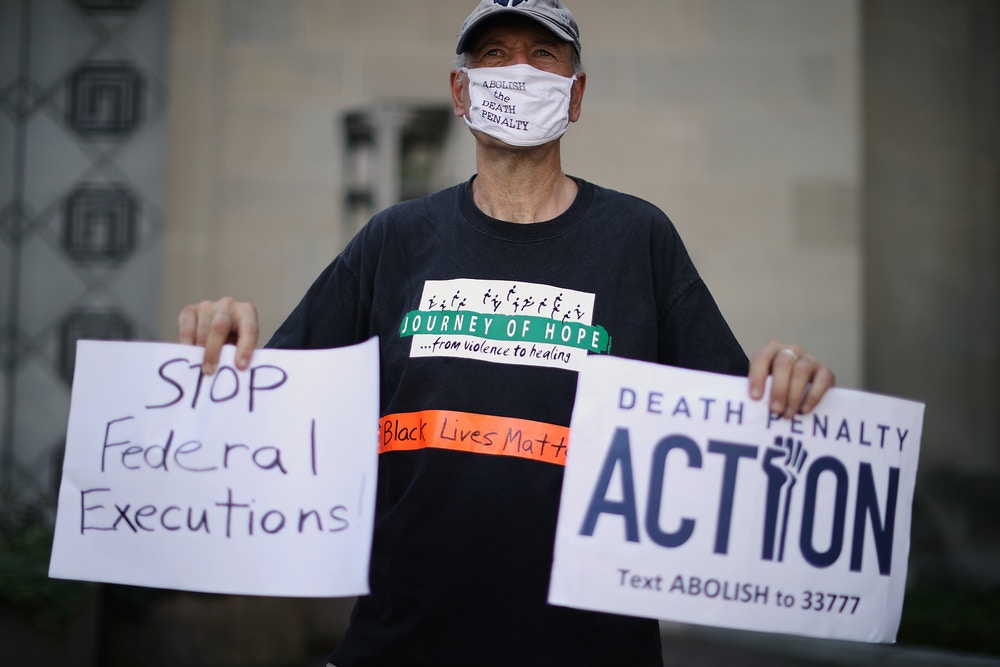

Photo: Jeremy Hogan/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty Images

Stunning Indifference

Preventing loss of life is supposed to be one of the reasons the death penalty still exists in the United States. Although evidence has historically shown that states with the death penalty on the books do not have lower murder rates than those in other jurisdictions, supporters of capital punishment continue to insist that it is a deterrent. Yet Trump’s executions have exposed the fallacy of executions as a policy carried out in the interest of public safety. In the rest of the country, where the pandemic largely stopped the death penalty in its tracks, some prosecutors nevertheless ignored public health warnings, pushing to move forward with executions and death penalty trials while fighting against exonerations of people on death row.

Trump’s executions have exposed the fallacy of executions as a policy carried out in the interest of public safety.

Scott Coffee, a 24-year veteran of the Clark County public defender office in Las Vegas, who is generally considered Nevada’s leading expert on the death penalty, said that his county is down to just one functioning courtroom — out of more than two dozen in normal times — and that at present, it can only handle short, straightforward proceedings, the polar opposite of a capital trial.

Capital cases are notoriously expensive and time-consuming. They require hours of research, investigation, and preparation by teams of lawyers and investigators; large pools of potential jurors; and expert witnesses who often have to travel from out of state — all things nearly impossible to accomplish amid a pandemic.

“The long and short is that these trials are being delayed for the foreseeable future,” Coffee wrote in an email to The Intercept, “irrespective” of prosecutors’ “desire to go forward.”

Nationally, there were just 18 new death sentences handed down across the U.S. in 2020 (none of them in Nevada), down from a high of 315 imposed in 1996, according to the Death Penalty Information Center’s year-end report. And there were just 17 executions, down from a peak of 98 in 1999; 10 of those executions have been carried out by the federal government. Three more were in Texas.

While support for the death penalty continues its steady decline, Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said that the number of new death sentences in 2020 was artificially low because of the pandemic. “We were going to be near record lows in death sentences and in executions anyway, because that’s just a continuation of the historical pattern,” he said. “But the depth of the decline this year is unquestionably attributable to Covid.” As such, he expects there will be some increase in new sentences in 2021, and particularly an uptick in executions, as officials who faced court-imposed stays and generally sought fewer new dates will undoubtedly try to make up for lost time.

The year saw other milestones too, those that have again highlighted the problems with capital punishment and those that point toward its demise.

Photo: David Zalubowski/AP

In May, Colorado became the 22nd state to abolish the death penalty, clearing its three-man death row. Colorado’s experience offers a stark example of the policy’s arbitrary and racist nature: In a state as white as Colorado, all three of the men on death row were Black, and all three were prosecuted by the same district attorney’s office.

Still, even as the pandemic worsened — and as abolition was all but inevitable — one Colorado prosecutor, Adams County District Attorney Dave Young, a vocal opponent of repeal, pressed impossibly forward, trying to quickly convene a death penalty trial against yet another young Black man. Hundreds of potential jurors were called to the courthouse, even though there was no clear plan to keep them safe from the virus. It wasn’t until the end of March, after Colorado Gov. Jared Polis signed the abolition bill into law and then ordered a statewide lockdown, that Young backed down and abandoned his efforts.

And despite the burdens the pandemic has posed across the system for lawyers and investigators, there were six death row exonerations in 2020, bringing the total number up to 173. Notably, Walter Ogrod, who’d been sentenced to die in Pennsylvania in 1996, was finally exonerated, after the Philadelphia district attorney’s office concluded that staggering levels of official misconduct had plagued his case, ultimately condemning the wrong man for the murder of 4-year-old Barbara Jean Horn.

Walter Ogrod, center, poses for a portrait with his brother, Greg Ogrod, and Greg’s fiancée, Mary G. Kelly, in 2019.

Photo: Courtesy of the Ogrod Family

It was a dramatic hearing, held via Zoom, during which an assistant district attorney with the Philadelphia DA’s office delivered an emotional apology to Ogrod, Horn’s mother, and the residents of Philadelphia — a rare occurrence for any actor in the criminal legal system, let alone a prosecutor. “The errors made in this case made the streets less safe and I fear that the true perpetrator … may have brought harm to others,” she said. “That is the impact of … wrongful convictions on our community.”

“This is what happens when the powers that be care more about appearances than due process.”

Indeed, the Covid-19 pandemic has revealed many of the ugly truths about the death penalty system that reformers and abolitionists have long recognized. Ogrod’s case is one example: A corrections department and judge demonstrating stunning indifference toward a man wrongfully condemned in a case where prosecutors and defense attorneys already agreed there had been a gross miscarriage of justice.

Nowhere was this kind of institutional callousness on greater display than in the Trump administration’s rush to execute federal prisoners even as the administration failed to control the pandemic. “I think the recent actions by the federal government of simply lining up as many people as possible for execution should frighten all of us,” Coffee said. “This is what happens when the powers that be care more about appearances than due process and serves as a stark reminder of why we need to repeal Nevada’s death penalty. Like many other states, we are but one leadership change away [from] committing the same atrocities.”

Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

An Inflection Point

For those on federal death row who survive both the virus and Trump’s killing spree, the future will largely depend on whether Biden lives up to his promises. Biden, who was instrumental in expanding the federal death penalty — and who was the last Democratic presidential candidate to come out against capital punishment — has remained silent about the killings in Terre Haute. After the last round of execution dates was announced in November, a spokesperson told the Associated Press simply that Biden “opposes the death penalty now and in the future.”

Even if Johnson and Higgs recover from Covid-19 in time for their executions, their lawyers warn that any lasting lung damage from their illness has already compounded the risk of an excruciating death. Medical experts, autopsies, and witness accounts have long raised red flags about the government’s lethal injection protocol, which shows evidence of causing flash pulmonary edema, a harrowing sensation akin to waterboarding.

Those who are still sick on death row are also at higher risk for bad outcomes. “This is another case of everything that goes bad with the criminal legal system goes worse for the death penalty,” said Dunham, DPIC’s executive director. People on death row are “uniquely vulnerable in multiple ways,” especially since they live in solitary confinement and under a high level of stress, which makes them especially susceptible to illness. “There is no comparable stress to being on death row,” Dunham said.

“These are people’s lives and we cannot trust the government to handle this policy responsibly.”

This has been especially true for the men in Terre Haute. In emails to The Intercept, death row residents have described the horror of watching friends and neighbors taken to die, coupled with a constant, pervasive fear of new execution dates. One man described it as a combination of “life-draining sadness” and impending danger. “This place is really affecting me,” he wrote in November. “When the guards do rounds, their keys clang and that noise is all of a sudden jarring, piercing my ears, hurting my ear drums, causing me major turbulence. And this never used to bother me.”

Dunham thinks 2020 may end up being an “inflection point” for the death penalty. “There are events that change the trajectory of debate on an issue. And there are points that death penalty opponents have been making for years — that this isn’t something you can trust with the government, because there’s always going to be somebody who’s coming in who is completely unreasonable,” he said. “This is not a toy. These are people’s lives and we cannot trust the government to handle this policy responsibly.”

Dunham is relatively optimistic that the failings of the system highlighted amid the pandemic may push additional states toward abolition. He thinks that it may be imminent in Wyoming, which has been on the cusp of repealing its death penalty statute for the past few years. Marguerite Herman, who is a member of the leadership team of the League of Women Voters of Cheyenne and among a diverse coalition of folks pushing for abolition in the state, isn’t sure that 2021 will be the year; a number of moderate Republicans who were on board, or nearly so, were voted out of office in November, making repeal less likely. Still, she remains confident that it will happen — after all, Wyoming’s death penalty isn’t exactly functional.

Four people have been sent to death row in Wyoming, according to a dataset compiled by The Intercept of more than 7,000 individuals sentenced to death in active death penalty states and the federal system since 1976. Of those four, only one has been executed. The other three have had their sentences overturned. Two were resentenced to life with the possibility of parole. The fourth is awaiting resentencing. Meanwhile, the policy has cost the state roughly $1 million per year.

As The Intercept’s dataset demonstrates, Wyoming’s experience with capital punishment is on par with the nation as a whole. Just 20 percent of the more than 7,000 people sentenced to die have been executed. A staggering 44 percent are no longer on death row for some other reason; the vast majority have had their sentences reduced, and hundreds have been released from prison altogether. Black people account for 40 percent of those sentenced to die. At least 51 percent of the total are people of color.

Even as politicians acknowledge the death penalty’s obvious failures, several seem content to put off abolition indefinitely. Pennsylvania has not used its death chamber since 1999; in 2015, Gov. Tom Wolf declared a moratorium on executions, calling the death penalty “ineffective, unjust, and expensive.” Yet more than 150 people remain on death row in the state. In California, where the execution chamber at San Quentin State Prison was dramatically dismantled almost two years ago, more than 700 people remain in limbo. Like Biden, Gov. Gavin Newsom could finish what he started and commute their sentences to life — a logical move for someone who has described the death penalty as “fundamentally immoral.” But such political courage is hard to come by.

As for Coffee, he feels that abolition in Nevada is on the horizon. It’s become a regular topic of discussion at the state Capitol, and he thinks the broader awakening around the failings of the criminal justice system combined with the fallout from the pandemic — the court disruptions, the loss of life, the economic destruction — may help more people realize what a fallible, barbaric, and ultimately failed policy the death penalty is.

“I am hopeful that the repeal efforts will succeed in this session. The move toward progressive criminal justice reforms has opened the eyes of many to the various problems inherent in the criminal justice system, but I have to say I can’t think of an area where this is more obvious than in the death penalty,” he wrote. “People are coming to realize that even if you believe in the death penalty, there is no fair, just, and accurate way to determine who deserves it. There are so many other places that the money wasted on this cruel endeavor could be spent that I hope, maybe, the end is in sight.”

This post was originally published on Radio Free.