After close to two decades of fighting, the U.S. war in Afghanistan might be close to an end. Against long odds, the Afghan Taliban seems not only to have survived its conflict with the United States but is today negotiating terms in Qatar-based talks about its future role in Afghan politics. One of the remaining issues in the peace talks is the matter of prisoners of war held by all sides. Thousands of Taliban prisoners have been released by the U.S.-backed Afghan government in recent months, part of a process intended to build goodwill and settle accounts from the conflict.

The U.S. itself also has an ongoing, direct role in prisoner releases — a delicate political situation that could create a hang-up in the talks. Thousands of Afghans have been held in U.S. prison facilities over the two long decades of the war, either in Afghanistan itself or at covert “black sites” abroad. Two of the U.S.’s Afghan prisoners, though, remain imprisoned at the U.S. detention facility at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba: Muhammad Rahim and Asadullah Haroon. Their fate has now become a point of contention in the peace talks, with the Taliban reportedly asking the U.S. to release them as part of any final agreement.

“They’re very much part of the negotiations, and the Taliban has both of their names down as people who they want released as part of a final agreement,” said Moazzam Begg, an activist with CAGE, a U.K.-based group that advocates for war on terror prisoners. Begg, a former prisoner at Guantánamo himself who has been briefed on the Taliban’s positions, said, “There have been talks about prisoners in other places held by the Afghan government, and those discussions have proven fairly fruitful. The two significant outstanding prisoners are Rahim and Haroon, held by the United States, and their status is one of the main points still unfinished.”

Rahim and Haroon are among the 40 prisoners still held at the Guantánamo Bay detention center, where the first prisoners began arriving 19 years ago on Monday. Their ordeals are exemplars of the prison’s excesses: Despite being held there for over a decade, neither has been charged with any crime. An Al Jazeera investigation into Haroon’s background published in 2016 casts doubts on the U.S. government’s allegations that he had been a commander for an Islamist militant group — a group that has since signed a peace deal with the Afghan government — and former courier for Al Qaeda. Instead, Al Jazeera found that little concrete information about Haroon exists in official documents, and its reporting suggested that his detention and rendition to Guantánamo arose from a case of mistaken identity.

Muhammad Rahim, a detainee at the Guantánamo Bay detention facility, photographed in December 2020.

Photo: Courtesy CAGE

Along with Haroon and a handful of others, Rahim has been cast into the legal black hole of being a so-called forever prisoner at Guantánamo Bay — someone whom the government is unable to charge with a crime yet also unwilling to release.

Separate from national security issues, the government has good political reasons to want to keep an aging Rahim imprisoned whether he poses a threat or not: the extensive torture he suffered in CIA custody. Details of Rahim’s torture at the hands of U.S. interrogators were included in a Senate report on the CIA-run interrogation program, describing a range of approved techniques used against him as well as their evident failure to generate any intelligence. The release of Rahim, as well as Haroon, whose lawyer said he was also tortured, could prove embarrassing for the U.S.

Medical Neglect

After nearly a decade and a half in prison, Rahim’s family said that along with the chronic injuries suffered as a result of torture, he has developed other serious illnesses in prison. Family members said that recent medical examinations at Guantánamo have discovered nodules in Rahim’s lungs and kidneys that early testing has suggested could be cancer, but he has so far been unable to obtain further confirmation due to a lack of sufficient medical facilities at the prison.

“Some tests have been done that indicate the beginnings of what is probably cancer,” said Rahim’s brother Abdul Basit, himself a former prisoner at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan, in an interview. “His wrist is also broken in two places, and that causes him constant pain that they don’t provide any proper treatment to help. Some of these injuries he has had for 14 years, from the time that they captured and tortured him.”

“After 14 years of torture, they have shown no charges and no evidence. People are playing political games, but he is a human being, and this is his life.”

Like many others who have cycled in and out of Guantánamo Bay over the years, the reasons for Rahim’s arrest and continued detention are murky. Although the prison was initially advertised as a place to hold the most dangerous accused terrorists — a depiction that has stuck in the public consciousness — former Bush administration officials have said that the government knew very early on that many people brought there posed little or no danger to the United States. Officials, though, felt compelled to continue holding the prisoners for political reasons: for instance, torture or chains of custody and reasons for detention that would prove embarrassing. Many men who were detained by foreign governments like Pakistan and renditioned to the United States fell victim to unscrupulous bounty hunters seeking to collect cash payments for finding terrorists or to conflicts between tribal groups seeking to use the U.S. military to settle scores with one another.

It was the latter situation that Abdul Basit claimed befell his brother.

Muhammad Rahim, center, teaches at a school in Afghanistan in the early 1990s. Rahim has been held at Guantánamo Bay without charge for 14 years.

Photo: Courtesy CAGE

“In Afghanistan, there are people in some tribes that are rivals of other tribes, some people from a tribe that was against ours named him falsely to Pakistani intelligence of being tied to Al Qaeda, and then they sold him on to the U.S.,” he said. “After 14 years of torture, they have shown no charges and no evidence. People are playing political games, but he is a human being, and this is his life. Muhammad Rahim’s children are growing up without him, and it is very painful for all of us to watch.”

Closing Guantánamo

The present effort to wind down the war in Afghanistan may prove to be a relatively bright spot in the Trump administration’s otherwise dismal foreign policy legacy. Senior U.S. officials, including Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, have held meetings with Taliban officials aimed at ending the conflict — a development that itself would have been unthinkable in years past. Some of those who are negotiating from the Taliban side during the current peace talks in Qatar are themselves former Guantánamo Bay prisoners.

The fates of Rahim and Haroon may now hold the key to ending the U.S.’s unhappy involvement in the Afghanistan war. President-elect Joe Biden has already signaled that he plans to continue the Obama-era approach of trying to wind down Guantánamo Bay. If, as is likely, peace talks with the Taliban continue with his administration, releasing Haroon and Rahim might offer a quick opportunity to kill two birds with one stone: reducing the size of a prison that has become a symbol of post-9/11 abuse while helping to conclude one of America’s most grueling forever wars.

“For Afghans in general, the detention of Afghan citizens in Guantánamo has been a problem and has remained a longstanding source of frustration for our partners there,” said Jarrett Blanc, a former Obama administration State Department official who helped negotiate a successful 2014 prisoner exchange with the Taliban that freed former U.S. captive Bowe Bergdahl. “In my experience working on Guantánamo issues, there are not many people in the prison who qualify as serious security threats. Even for people who were considered dangerous or were alleged to commit criminal acts, the Afghan government has wanted to deal with them themselves. Their detention by us at Guantánamo has been viewed as an affront to their sovereignty.”

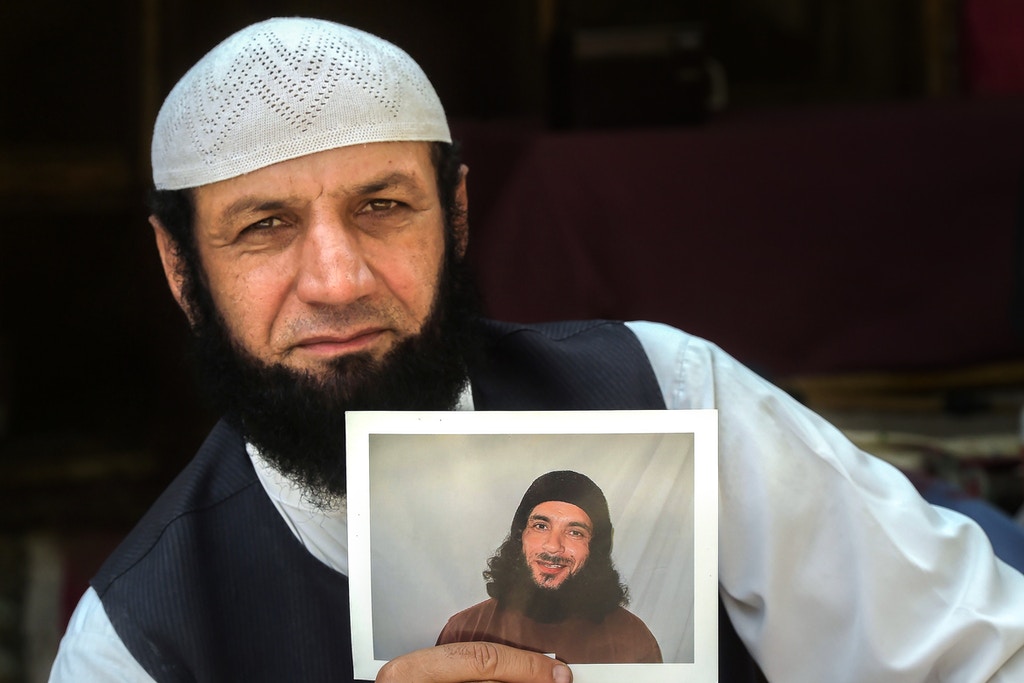

Roman Khan holds a photograph of his brother, Guantánamo prisoner Asadullah Haroon, in Shamshatu refugee camp near Peshawar, Pakistan, on Sept. 25, 2020.

Photo: Abdul Majeed/AFP via Getty Images

In a world of trade-offs, releasing detainees now also happens to be a concession that other former U.S. officials say risks relatively little to national security. Afghanistan has been wracked by a civil conflict that predated the U.S. invasion and is likely to continue even as the American troops begin to withdraw. Many detainees at Guantánamo over the years were themselves participants in this intra-Afghan conflict that the U.S. was sucked into. Keeping Guantánamo — a symbol of U.S. disregard for human rights and the rule of law — open, even while the people inside have often proven innocent or insignificant to the global war on terror, seems likely to do more harm than good.

“If anything,” wrote Ben Farley, a former State Department official focused on Guantánamo closure during the Obama administration, “continuing to detain these men as years stretch into decades increases the risk of compounding the reputational harm incurred when the United States opened GTMO, hampering counterterrorism cooperation, suffering disadvantageous decisions from reengaged federal courts, mythologizing foot soldiers and ordinary criminals into Rambos or Bond villains, and inspiring nonparticipants to take up the fight against the United States.”

This post was originally published on Radio Free.