(ar-chi / iStockPhoto)

In October, Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer signed legislation that will, eventually, automatically expunge a misdemeanor from a Michigander’s criminal record after seven years, as well as some felonies after 10 years without another conviction. The legislation makes Michigan one of a few states, including New Jersey and California, to include some felonies in automatic expungements.

Experts estimate the legislation will have wide-reaching impact on people with felony records, who face barriers to getting a job. In Michigan, people with convictions are even required to self-report criminal records to the state’s Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs when applying for most types of professional licenses, including barber’s and beautician licenses.

The law was supported by a bipartisan coalition that included conservative groups like American Conservative Union and Americans for Prosperity, a sign that the criminal justice system has impacted people across the political spectrum, according to Joshua Hoe, policy analyst for the non-profit Safe & Just Michigan, which supported the legislation.

“So many people have been directly impacted,” Hoe says. “Once they’ve seen up close they’re much more interested in trying to change these laws.”

Now advocates hope the law will allow people to fully participate in society without the shame or stigma of a criminal record. Eileen Hayes is executive director of Michigan Faith In Action, a faith-based non-profit that advocated for the legislation. She was troubled by the system’s failure to provide redemption to people who’ve completed their sentences.

She recalls one man who testified in favor of the law that he hadn’t been incarcerated for ten years, but still had trouble finding work due to prior convictions. “As people of faith we’re all about second chances. How long do you have to pay for something you did over 10 years ago?” she asks.

Support for automatic expungements was bolstered by research by JJ Prescott, a law professor at the University of Michigan Law School, and Sonja Starr, a professor of law and criminology at the University of Chicago Law School. The duo looked at data provided by the Michigan State Police – with personal information removed — for people who received expungements since 2014, along, with a larger cohort who had not. Their research showed the rate at which people with convictions eligible for expungement were getting their records cleared was just 6.5 percent within the first five years of being eligible for one.

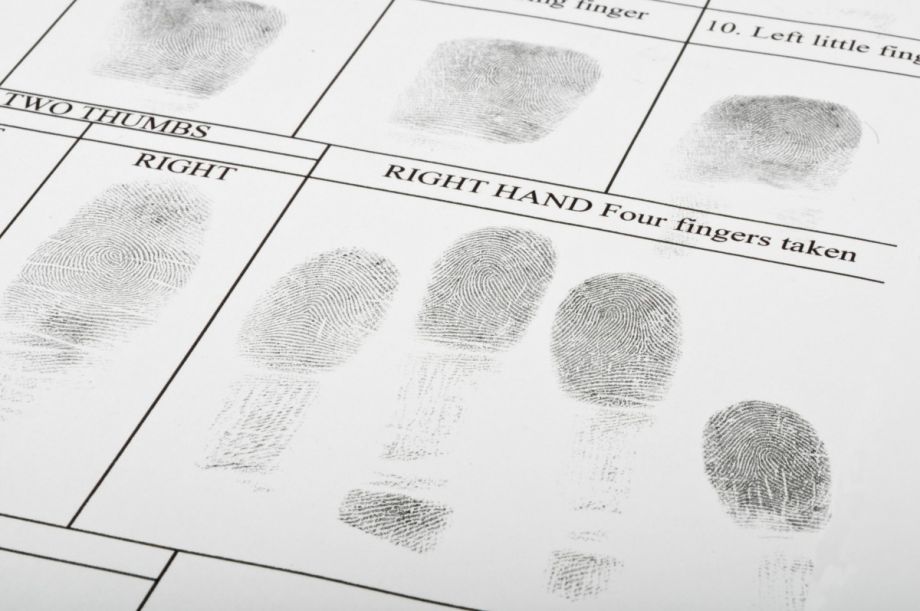

Prescott says the reason for the low uptake of expungements is that the process is too complicated and long. Eligibility was narrow prior to recent legislation; people with felony offenses were eligible to petition the court if they had no more than two misdemeanors and five years had passed from their sentencing. Those who met those requirements could begin a long application process that involves getting finger-printed at a police department, mailing multiple copies to the attorney general’s office and paying a $50 application fee.

“You look at this population which has less money to begin with, it’s maybe not

so surprising that you have such a low uptake rate,” Prescott says. This led Prescott to ask, “if we actually think people who have satisfied requirements are due a clean slate, why not grant it automatically?”

Prescott says he had to counter fears that expungement would not be safe and that employers should be warned about criminal records. His research showed the recidivism rate for people with expungements was 7.1 percent, on par with the average for Michiganders. One theory as to why this is, he says, is that,“by giving people the clean slate they’re better able to obtain housing and employment and improve their lives.” In other words, people are less likely to commit certain types of crimes when their basic needs are being met.

Moreso, Prescott’s research found that employment and wages went up dramatically for the cohort with expungements, by 20 to 25 percent on average a year after their record was cleared. “Poverty and unemployment are huge risk factors for crime,” Prescott says, and he believes the increase in wages and decrease in recidivism proves that expungement improves lives without hurting public safety.

Prescott says there’s another rationale for providing expungements automatically rather than through a prolonged bureaucratic process — the longer it takes, the worse the long-term career impacts. “A lot of the damage with someone’s career prospects happens in the first few years,” he says.

Even before the current state-wide clean-slate legislation passed, the City of Detroit became more proactive about helping people clear their records. Mayor Mike Duggan set up a dedicated office in 2016 to handle expungements called Project Clean Slate, with three full-time attorneys on staff. The attorneys handle all the paperwork for people petitioning the court to have their records expunged: ordering court records, helping people get fingerprints done, and arranging for transportation to appointments, according to Carrie Jones, who works at Project Clean Slate.

“It was a way to move the needle for people’s lives as it relates to finding better jobs and employment,” explains Jones. Their clientele was growing even before the recent change in the law. She says in 2017, the office handled 8 expungements, and in 2018 they handled 129. As of October, the most recent month data was available, the office was on track to handle 280 expungements by the end of 2020. A report found that expungements handled through Project Clean Slate had nearly four times the impact on job prospects as traditional job training.

Michigan’s new clean-slate legislation contains more provisions than just automatic misdemeanor expungement, which will begin to take effect in 2023. People can still petition to have criminal records expunged, and the legislation expands the number of misdemeanor convictions that are eligible for expungement and reduces the waiting period for petition-based expungement from five to three years. Automatic expungements under the law will not take effect until 2023, but the expansion of eligibility for petition-based expungement will begin in April.

Jones says Project Clean Slate’s clients were avidly paying attention when the state-wide legislation was passed, and she immediately started getting calls and e-mails from people wanting clarity.

The amount of Detroiters who will be eligible for expungement will more than double when the law takes effect, from an estimated 82,000 to 168,000, Jones says. Project Clean Slate plans to increase staff and draw on a network of volunteer attorneys to help with the additional load.

Jones has seen the impact on people’s lives through her work at Project Clean Slate. She said one of her clients went from a job making $10 an hour to being able to apply to jobs making $26 an hour. For another client, it cleared the way for her to go to nursing school.

The recent expansion of the expungement law has its critics among reformers who feel it leaves some out needlessly by omitting assaultive crimes, DUI’s and certain types of sex offenses. Prescott argues it makes little sense to leave some people convicted of more violent crimes out of automatic expungement.

“If the theory is, we’re trying to identify people who are no longer of significant risk and also give people an incentive to work hard to improve their lives,” Prescott says, “there’s not a lot of good evidence that we ought to draw a line between people who committed a crime of violence or an assaultive crime, versus somebody who committed a property crime or something. The differences are fairly small between these categories. The recidivism rates for all of them are low” after expungement, he says.

And there are benefits to expungement that extend beyond job prospects. “Ninety percent of our clients say they’re seeking expungement because they are looking for better career and employment opportunities,” Jones says. But she says when surveyed after their expungement is processed, 86 percent of people say the strongest benefit is removing the stigma of a criminal record. “There are a lot of economic and employment benefits,” says Jones, “but there’s also a great benefit of having that weight lifted.”

This article is part of The Clean Slate, a series about how cities can use technology and policy to eliminate unjust fines, fees, and other barriers to economic mobility. The Clean Slate is generously supported by the Solutions Journalism Network.

This post was originally published on Next City.