New research has plunged Universal Credit into further chaos. It involves the debate around the £20 a week uplift. A charity has claimed that without this, Universal Credit will be worth less than in 2013.

But The Canary has done its own research. And we’ve found that the problems with the Department for Work and Pensions’ (DWP) flagship benefit and the uplift are actually worse than even this new research thought. Because some people could be nearly £440 a month worse off than before.

DWP and the Treasury: at war

In April 2020, the DWP increased the rate of Universal Credit by around £20 a week. But ever since then, uncertainty has existed over what will happen this April. Now we know the Tories are ending this increase in April, and people will see a £20 per week cut to their payments.

Chaos has ensued in government. At first, chancellor Rishi Sunak talked about giving Universal Credit claimants a one-off £500 payment. Then, he was allegedly thinking about making this £1,000. But the DWP boss Thérèse Coffey ‘slapped down‘ Sunak’s idea. She said it was not her department’s “preferred approach”, but did not say what the DWP’s answer would be.

On 9 February, the Work and Pensions Select Committee warned of a rise in poverty not seen since the 1980s if the government did not keep the uplift. And now, research has further strengthened the argument for keeping the extra £20 a week.

Universal Credit: worth less than in 2013

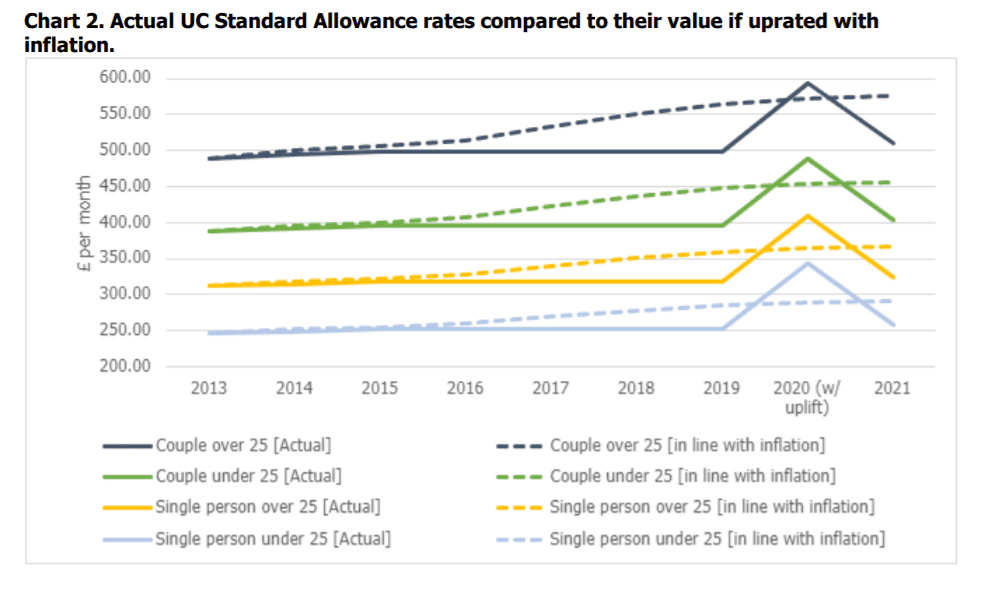

Citizens Advice Scotland (CAS) has done some calculations. It has looked at the standard allowance rates. These are fixed amounts the DWP pays people depending on their circumstances. It was this part that the government increased by £20 a week. CAS has worked out how much the allowance is worth in real terms; that is, what the actual amount of money the DWP pays is worth when you factor in inflation. It said that, if the government removes the £20 a week uplift, then across all circumstances the standard allowance will be worth less in real terms than it was in 2013:

CAS is calling for the government to keep the uplift. It noted some case studies of how a reduction in Universal Credit would affect people:

A West of Scotland CAB reports of a client with a young baby facing financial difficulties as a result of unexplained deductions to her benefits. Client’s deductions are around £50 a month, meaning removal of the uplift will push her into more severe hardship.

An East of Scotland CAB reports of a client moved over to UC as she would be £12 a week better off than on legacy benefits. Cutting the £20 a week UC uplift will make her materially worse off than she was pre-pandemic.

But CAS has missed another point about the uplift. Because it hasn’t calculated the effects of inflation on overall payments; not just on the standard allowance.

Canary number crunching

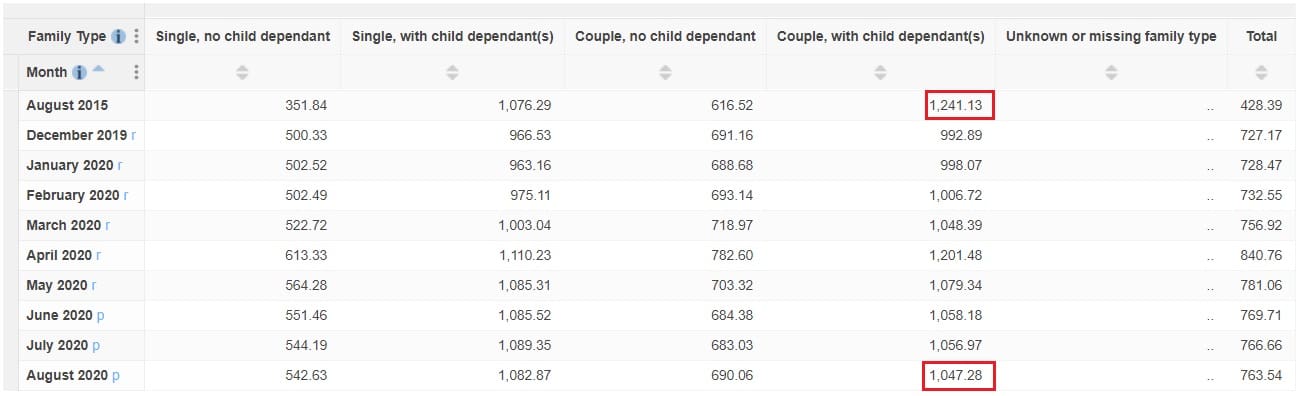

The Canary has crunched the numbers. DWP figures for mean (average) overall Universal Credit payments only go back to 2015. But as its figures show, couples with children already on average got less money in August 2020 than they did in August 2015. This is with the uplift:

Then, factor inflation into these figures. The results are shocking.

Systemically broken

This would mean that:

- Lone parents are £137 a month worse off. Without the uplift, this would go up to around a £217 a month loss (based on four calendar weeks, without inflation).

- Couples with children are £359 a month worse off. Without the uplift, the figure is around £439.

- Couples with no children are £8.31 a month worse off. Without the uplift, this is around £88.

The only group which is better off now than in 2015 is single people with no children; to the tune of £144 a month. But even this is reduced to just £64 if you take off the uplift.

All this is without even touching on the around 1.5 million claimants of things like Employment and Support Allowance (ESA). The government hasn’t given any extra support to these people at all during the pandemic.

Universal Credit has been a disaster from the start. And while an extra £20 a week is crucial, it’s just a tweak in a system that’s already broken. Entrenched poverty and inequality are now a systemic fault in our social security system. No amount of tinkering around the edges with £20 here and there is going to solve that.

Featured image via geralt – pixabay, Wikimedia and Wikimedia

By Steve Topple

This post was originally published on The Canary.