Your work involves sculpture, scent, performance, fabrics, design. When you have an idea, how do you decide which form the idea will take?

When I’m thinking about something new to create, the material, the medium, the shape, the light, the density, the message, the story, all that takes place at the same time. At the end of the day, if something has to be made with the feathers, it would be feathers because that’s where the process took me. Has to be lacquered, well, it’s going to be lacquered. If it has to be a performance, it will be a performance. I don’t really have the kind of thinking process where I separate the idea from the medium or the message—everything really comes together in my mind.

Have you ever started a piece and while it’s just starting to come together, lost interest in it or, if you start something, do you tend to complete the project?

It’s fairly rare I’ve changed direction while doing something. A slight diversion maybe. But change direction suddenly and stop, that doesn’t really happen. It takes me so long before I decide to get involved in something that it’s usually nearly finished. I have a clear mental image, or a sound image, or a visual image. When it takes shape in 3D dimension, I tend to finish what I start.

When you started out, you were doing car design. How did you decide you would work on that? Was art something you always did on the side? Or was it something you did in tandem with designing?

I did art school, then design school, then I joined an automotive maker in France to design cars. Then I was sent to Japan. While I was in Japan, I felt like doing a side project. And the side project was about trying to tell a story about where I come from and also where I lived in Tokyo. I couldn’t do that at work, so I took some more time outside my office work time to explore that new territory, that new vocabulary, that new field, that new aesthetic that I came to create.

When you started doing this as a side project, did you think of yourself as an artist? Or did you think, “I’m a car designer and I’m doing this as a side project?” Because I know for a lot of people I talk to, they always, there’s a moment where they’re like, “Oh, wait a second, I’m an artist.” Did you always think of yourself as an artist?

To be honest with you? I don’t see myself as anything else but just someone who likes creating things. Artists, non-artist, designer, non-designer. For me, the frontiers are very blurry. It’s a question of life or death. Either you really need to do it and you have to do it and you do anything it takes to do it, or you don’t really need to do it. I’ve done it because it was a question of putting together a story that would help me answer some questions I had at that time, at that moment.

It wasn’t really a question of knowing if I was either a designer or an artist. It was knowing that something had to be done. And I put all my energy into that side project, regardless of the time constraints, of the fatigue, of the difficulty to build something in Japan when you’re not Japanese, and to put it together, and have an impact on Japanese people. I don’t know if I’m an artist, I’m just someone who likes doing stuff.

I feel that way, too. I was talking to a class earlier today; my friend teaches at a school in Philadelphia and asked me to speak to his class about becoming a musician, making music. I said to them you can make things and not share it with the world and that’s still art. You can make something just because you need to make it. You don’t need to share it with anyone and that’s still very valid. If you made this work and nobody responded to it, would you still keep making it?

Absolutely. I don’t have an Instagram account, I don’t have Facebook, I don’t have Twitter. I just like to do what I do. If it has an impact, great, if it doesn’t have any impact, I would still do it because it responds to some fundamental question I have about being a human, about the question of identity. Since I believe that identity now seems to be a fantasy, really. Most of what we believe is our identity is probably 70% fantasy. That’s the conclusion I draw from my work. Artists or not artist, if you’re a cook and you need to try it, who’s going to stop you, if you really believe you have to try those ingredients and cook them under the sun, put them under the earth for four or five hours, let the sun hit them through the sand, pick them up, smoke them, slide honey on it, spray with some kind of, I don’t know what ingredient. If you feel like you have to try that, you just do. You don’t look and see if people are looking or staring at you and congratulating you.

You were saying, you think 70% of identity is often a fantasy. Can you explain that a little bit more, this idea of identity?

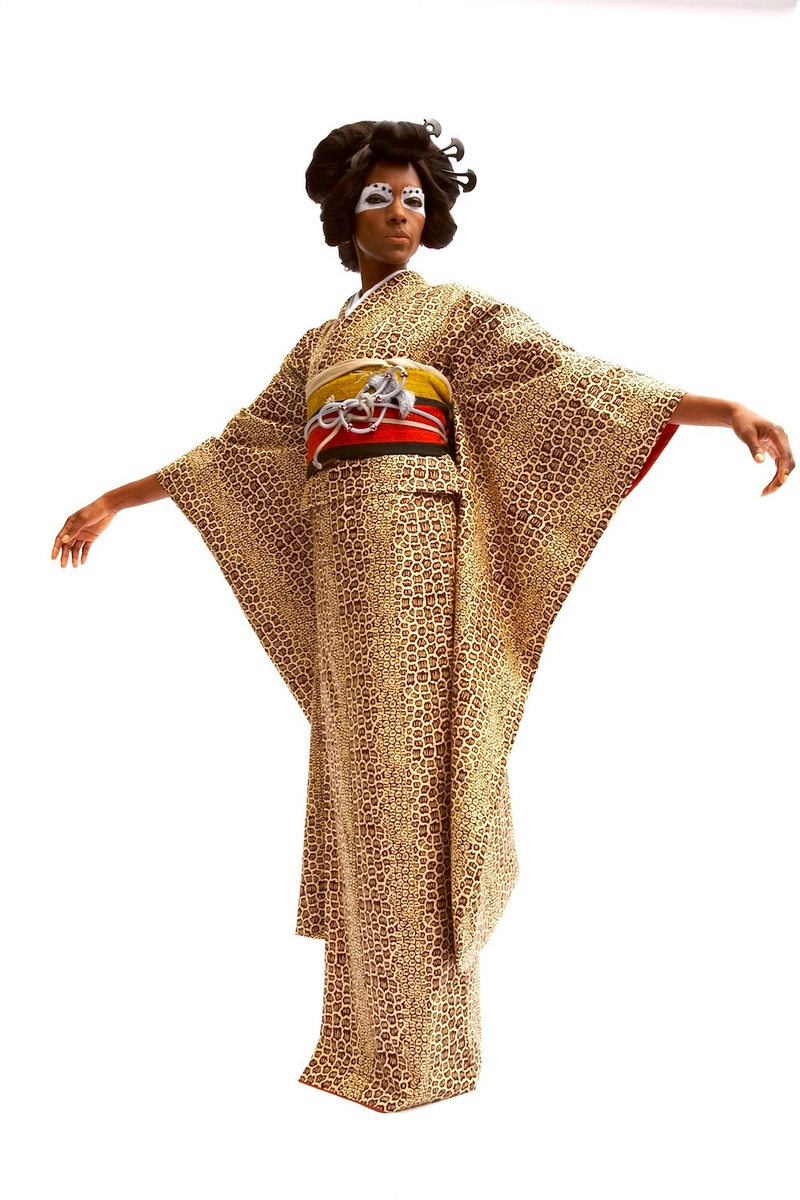

Some people came to me and said, “Oh, you design kimonos with, you said African fabrics, but those African fabrics are wax and wax is made in Holland and in Holland, they don’t know too much about Africans taste and things like that.” I said, yes, it’s true. They’re made in Holland, they’re made in Switzerland and they’re made in Africa as well. The fact is, African people wear them and when you see the fabric, you connect them with African people.

Coffee doesn’t come from Italy. Of course, they don’t have any coffee fields, it came from, I think, Ethiopia. The original name of coffee is Ethiopian. The same as kimonos. Kimonos didn’t come from Japan, they came from China originally more or less, as far as we know. And the wax techniques are from the Danish; the wax fabrics come from Indonesia.

It’s okay to defend identity, as long as you know that most of it is fantasy. You can defend your identity, but make sure it doesn’t take a scale of emotion that will not make sense if you look deep inside the facts of what happened to build that identity.

So much of your art involves identity and community and gathering…Now that we’re all separate, how do you stay focused on what you’re doing? How do you stay optimistic? How do you stay engaged with the work and feel good about it?

I’m a positive person in general. I’m not the kind of person who gets de-motivated quickly. Unfortunately for some of my family members, when I start something, it’s hard to stop, it’s very difficult to stop. I can’t stop, I don’t know how to stop. I would have to have, even… No, I don’t… I can’t stop, there’s no retirement for me. It doesn’t exist and I’m bringing people together. I have noticed also that when I work with people, it seems they understand fairly quickly where I’m trying to go and they easily get it, bond with the idea and work overtime to succeed, so that we can succeed all together. They like the message, they believe in that there’s something more to tell. There’s a deep story about who we are as a human species.

Have you ever had burnout? Have you ever reached a point where you just had to stop because you work too much or were juggling too many projects?

Never. I sleep a lot during the weekends. I like to stay in bed and do nothing at all, I love it. And just stare at the ceiling and just sit there. I think that’s when I’m the most productive. When I lie down in bed and I stare at the ceiling, there’s so much happening in my head. And when I stand up, it’s all done, things are set up and I just have to execute. I’m a big observer. I’m very contemplative as well, I contemplate things, sound; I love sound. So, no, I don’t burn out. I don’t know what may happen to me but for the moment I feel like I’m in a cloud and I’m not really here. I’m not really where I am.

Do you work from a separate studio or do you work from home? You were saying you like to lay it out and observe, do your ideas come from your everyday surroundings or do you like to remove yourself and work from a separate spot?

Most of my ideas come from a situation where I’m alone. Walking, listening to music, and having a movie take place in my head, in my ears. That’s how ideas get captured, then they go somewhere in the corner of my head, they come back hours, weeks after. They grow and they grow and they grow again and they get simplified and they have a trajectory in my head, until the moment where they can’t really go anywhere else. They have to be built, they have to take shape.

I’ve got my studio here in the basement of my house, it’s a good space. I have the garden right outside here, there’s a big window. We have a nice piece of land and that’s where the ideas come from. Or I have to go outside in Paris and walk; or again in Tokyo, walk; or when I’m in Africa and I see people, I hear stories and connect things.

As long as you have imagination, things can start coming together in your mind. Those are the most important tools to your practice, really. Just having that initial idea then giving it the space to grow, essentially.

Yes. And trusting where these ideas are going in your head. Just let the idea travel in your head. Trust in the idea until the idea itself says, “I need to get home. I need to get outside.” That’s when you have to execute it.

Have you always had such confidence in your ideas or did it take time to develop that sort of confidence and letting things grow on their own and giving them the space to grow?

Honestly speaking, I’m not bad at creating what doesn’t exist yet. That’s something that I know how to do. So I tend to trust my ideas, often. It may sound a bit arrogant but at my age, that’s one of the conclusions that I have. Not that the ideas are always good, but I trust them enough to give shape to them to the end and then see if it’s worth it or not.

I feel like it takes a while to reach that. When someone’s first starting out, maybe they’re a teenager, you don’t trust the ideas necessarily, but yeah, as I’ve gotten older, I’m like, “Oh yeah, I’m going to go with this thing, I trust it.” It saves so much more time; it makes you more efficient when you have trust in your work. You just kind of let it go.

Exactly. You’ve said it, it makes you more efficient because there’s a system; you throw away what’s not interesting and keep what’s the most constructive and worth doing. At the end, the path has taken place by itself and you just have to accomplish what you had in your head. The environment and improvisation is important as well. For me, in West Africa, to improvise is key. I often had that problem where at work in the corporate design space, you have to prepare [rather than improvise]. We rehearse so much before we present something. Whereas naturally, I just know what I have to say or what I have to show or what I have to do.

Something I read in the description of your work was how you realized that in African culture there’s spontaneity and improvisation and perhaps in Japanese culture, more scheduling and things like that. You have the idea and you trust the idea, sure, but once it comes out and faces reality, you have to allow for improvisation and shifting in the idea. You can’t just be like, “This is the only idea,” because maybe it changes once it’s outside of your head.

In Japan, one of the things I struggled with was the fact that everything is planned. That there’s no room for improvisation means you’re taking a risk of losing face or of not being organized and missing the point because everything is based on harmony with execution. In Japanese culture, you are very much attached to execution. It’s not about conceptual ideas, how crazy your ideas are. It’s how you execute things. That’s what’s important. It’s better to repeat something perfectly than to take the risk of trying something new that is not finished. Whereas, where I originally come from, you have to adapt to new things all the time because you simply may die.

The environment is dangerous. It’s different. You have to be extremely flexible with how you behave every day. Whereas in Japan, things are safer, let’s say, and you want to keep them safe. There’s no room for someone who’s either too messy, too creative, too challenging, too individual…Those concepts are not the safe concept. The group, the consensus. You have to be team spirited. It’s a different kind of position to how you socialize in Japan and in Africa, there’s a lot of difference on that aspect, while there’s lots of connections as well.

Do you ever wonder, if you had not gone to Japan for work, what kind of art you’d be making?

I think I would be more of a conceptual artist. Too conceptual, I think. It really made me reconnect with West Africa and also with the culture that I didn’t really know, the culture where you have to show things, you have to again, as I said, execute things. You have to do them. You don’t talk so much in Japan because it’s dangerous, it’s weak, it’s not well seen, someone who talks too much. So although those things were new for someone who was born in Africa and raised in Europe; in France, in Japan, it’s a very different perspective. You don’t speak so much. I would have become much more of a Western conceptual artist so to speak.

Serge Mouangue Recommends:

Draw. Make your autoportrait. Especially if you think you don’t know how. You will produce the most unpredictable inner photographs.

Walk.

Find your delightful soundscape location on the planet.

A country like Japan with low natural resources, regular earthquakes and typhoon, unfriendly neighbors, constant nuclear hurdles through history and very limited living space with high density. This culture made determination a survival and competitive mantra. From my African eyes it is literally stunning.

This post was originally published on The Creative Independent.