ANALYSIS: By Tony Fala

PART 1: Divide and rule with Māori and Pacific communities

White Supremacy (WS) has proliferated during covid-19 lockdowns in Aotearoa from 17 August 2021. Supremacist activism, aspirations, attitudes, behaviours, beliefs, concepts, ideas, languages, media output, organising praxes, political slogans, political thought, and political party policies have all flourished as people protested against government covid restrictions and lockdowns.

In this writing, I distinguish between anti-vaccination and freedom protesters who are not advocating for WS and those who are part of anti-lockdown protests and anti-vaccination organising who do support white supremacy.

Similarly, the focus of this commentary is not to examine conspiracy theories. Moreover, I am not seeking to examine the work of Māori or Pacific people engaged in anti-vaccination and freedom from lockdown protests.

- READ MORE: Covid disinformation and extremism are on the rise in New Zealand. What are the risks of it turning violent?

- Ardern loses the gloss as New Zealanders protest about covid restrictions

- Other reports on covid disinformation

WS works best when it can divide and rule Māori and Pacific communities. My focus in this article is on Pakeha involvement in WS as it evolves in contemporary Aotearoa.

This article seeks to offer ways to understand the contemporary emergence of the supremacy phenomenon. This article will offer a thumbnail sketch outline of some of the features of supremacy in an Aotearoa context.

I assume colonial and historical forms of WS already existent in Aotearoa are coalescing and are being energised by contemporary, hybrid variations of supremacy emerging from the US, Europe, Australia, and other countries.

Supremacists in Aotearoa are clearly drawing upon WS activism, aesthetics, hostility, media output, messaging, modes of organising, and political thought from overseas.

White supremacy in Aotearoa

I attempt to group these variegated expressions of white supremacy in this article. I seek to outline this phenomenon as a composite of ideas, concepts, languages, beliefs, ideologies, attitudes, activisms, praxes, aspirations, narratives, and political positions — all situated in a time, space, and condition in Aotearoa.

I feel that WS must also be understood as embodying modes of being, living, and knowing operational in community, family, political, and social life. WS is occurring at multiple levels of our communities.

Further, I believe people must be able to analyse WS; group supremacist phenomena, and assess it vis-à-vis a framework such as a spectrum. Further, we must invite African, Asian, Māori, and Pacific, and Pakeha communities to consider WS from within values specific to each cultural group.

Most importantly, we must invite community groups to question WS from their many different community standing places. I hope this modest work offers communities a framework for assessing WS from within their own flax roots community perspectives.

We need more work considering these issues from the perspectives of women, LGBTG, working class, and disabled sectors of the wider community also.

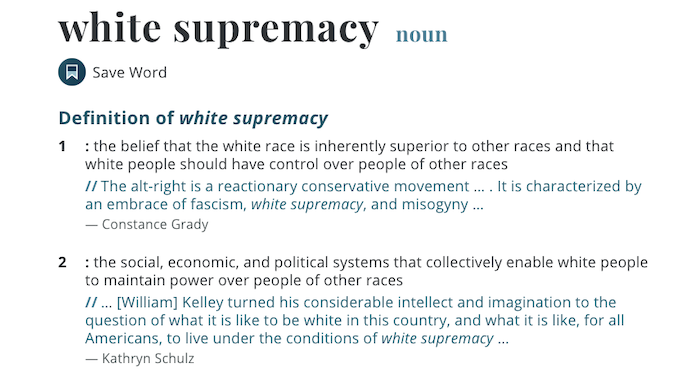

The online Merriam Webster Dictionary defines WS in two ways. Firstly, WS is defined at its most basic as “the belief that the white race is inherently superior to other races and that white people should have control over people of other races”.

In this definition, WS is defined as a component of an attitudinal sphere.

Secondly, the Merriam Webster Dictionary defines WS as “the social, economic, and political systems that collectively enable white people to maintain power over people of other races”.

Structural and societal level

This shifts discussion of WS from an individual attitudinal sphere to a structural and societal level. I deploy both these definitions of white supremacy in this article — and expand upon the definition in regards to specific concerns such as activism, language, and the media.

I argue white supremacy is one component of a wider colonial settler project in Aotearoa. Alicia Cox at Oxford Bibliographies defines Settler Colonialism as “an ongoing system of power that perpetuates genocide and repression of indigenous peoples… normalises continuous settler occupation… exploiting lands and resources to which indigenous people have genealogical relationships…includes interlocking forms of oppression such as racism, white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, and capitalism”.

In sum, I will argue that all forms of WS outlined in this article contribute to Settler Colonialism in Aotearoa.

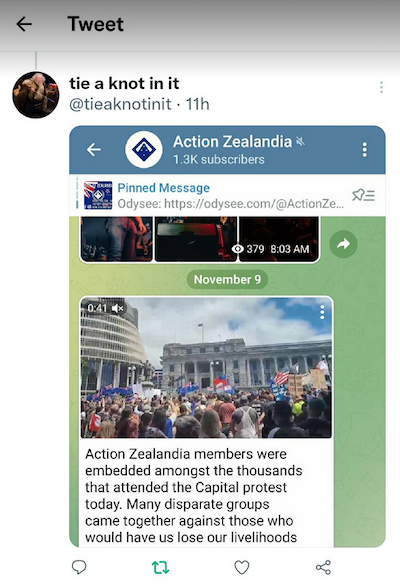

I have examined commentary, comments, interviews, and video footage of well-known Pakeha WS activists and media pundits in Aotearoa. I have examined Facebook, Twitter, Tiktok, and internet commentary from flax roots people. I considered fringe parliamentary political parties’ policies of those positioning themselves for entry into mainstream politics.

I viewed video footage of freedom and anti-vax protests around the country. I looked at internet sites of groups organising anti-lockdown protests around Aotearoa. I researched QAnon, the ALT-Right, and white supremacist organisations overseas. Similarly, I read work on concepts, language, and political thought underpins some of these movements.

I see WS as a formation existing along a spectrum for the transformation of specific sectional interests; for those seeking to use direct action to challenge the government; for those seeking representation in Parliament, and finally for people seeking a potential white ethno-state.

We should be sensitive to the aspirations, attitudes, beliefs, concepts, ideas, use of language, and ideals concerning economic, social, and political thought underpinning WS in the list introduced below.

Expressions of WS

When examining sources I found expressions of WS regarding:

(1) contempt for Te Tiriti,

(2) rejection of power sharing between Pakeha and Māori as articulated in Te Tiriti,

(3) appropriation of He Whakaputanga alongside a rejection of Te Tiriti,

(4) antagonism towards the historical experience of Māori,

(5) privileging of a mythology of “peaceful” or “just” race relations in Aotearoa — thereby erasing histories of racism suffered by Africans, Asians, Māori, or Pacific communities in Aotearoa,

(6) political policies of different fringe parties antagonistic to “race”-based privileges for Māori in health, in law, or at the United Nations,

(7) vilification of the NZ Labour as “socialistic”,

(8) attacks on Māori activist, community, political, or scholarly leaders,

(9) assumptions WS is on same side as “ordinary” Māori, Pacific, Asian, African, or Pakeha communities,

(10) attacks on independent university based critical scholarship,

(11) abuse of Māori language users,

(12) championing of bellicose forms of Pentecostal Christianity as the only legitimate faith for Aotearoa,

(13) attacks on the United Nations and governments as cabals of evil,

(14) contempt for migrants rights,

(15) deployment of language hijacked from liberation struggles,

(16) deployment of narratives of WS,

(17) refusal to debate honestly,

(18) antagonism and personal attacks against those considered enemies of WS using different media,

(19) articulation of action programmes,

(20) modes of praxis,

(21) introduction of Alt Right and QAnon concepts, language use, and values, and

(22) lauding of former US President Donald Trump, Republicans, and Q.

I deploy one example of the techniques Pakeha WS proponents use to articulate their programme re language hijacked from liberation struggles. Pakeha WS adherents have sought to appropriate, disrupt, interrupt, colonise, and then occupy the languages of Māori and African-American liberation — and, implicitly, the epistemologies underpinning these languages.

For example, Pakeha WS figures have called acclaimed Māori community leader Hone Harawira a “sell out”, a “house negro”, and a “traitor” for his community work for Māori families during covid-19 lockdowns in Northland in 2021.

Here, WS folk have attempted to colonise the Black Liberation language of Malcolm X. This “house negro” language was deployed by Malcolm X in a specific time, place, and condition- as Manning Marable articulates in his controversial history, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. Māori activists deployed this language in debates with their more conservative elders in years gone by.

But Pakeha WS advocates deploying this language are no friends of Malcolm or the Black Liberation struggle — these Pakeha are bitter opponents of the BLM movement. Similarly, these Pakeha are no friends of Māori liberation struggles such as the one at Ihumatao.

The whakapapa of struggle

WS adherents are trying to colonise, disrupt, and occupy this language so as to appropriate it to better undermine the links connecting Hone to his own people. But Hone is conjoined to his people by whakapapa and the whakapapa of struggle.

Moreover, who would Malcolm X stand with? WS representatives attacking indigenous people — or an indigenous Māori brother, like Hone Harawira?

I invite Asian, African, Māori, Pacific, and Pakeha communities standing in their own cultures, community values, experiences, and histories to consider these questions.

Does WS in its various forms as outlined in brief above:

(1) Resonate with your community values?

(2) Articulate your vision of the country?

(3) Uphold the mana of the diverse sections of each of your communities?

(4) Sympathise with your communal experiences or histories?

(5) Align with your notions of community service?

(6) Voice your community needs?

(7) Articulate your community aspirations for your young people, women, or your elders?

(8) Support your concerns in the parliamentary party sphere?

(9) Offer a valid means to find a way out of covid-19 in a time of great uncertainty?

(10) Make Aotearoa/New Zealand a safer place for your community?

(11) Make Aotearoa/New Zealand a more tolerant society?

(12) Uphold the mana of the first people of this land, the Māori people?

(13) Offer a means to advance the concerns of all communities in Aotearoa?

(14) Does settler colonialism offer a positive vision for a united and prosperous Aotearoa/ New Zealand in the future?

Only communities in Aotearoa have the answers to these questions. I hope the definitions, analysis, articulation of a spectrum, and the final questions provide an accessible and safe framework for communities to assess, critically engage, and strategise concerning this contemporary phenomena known as WS.

Tony Fala is an activist, researcher, and volunteer for a small charitable trust engaged in food rescue and distribution to communities in South Auckland. He acknowledges his own racism in years gone by — something he had to overcome. Fala wishes to acknowledge the anti-racist contributions of Joe Carolan, Tina Ngata, Rawiri Taonui, and Joe Trinder — and all other activists, journalists, and scholars engaged in responding to WS. He also wishes to acknowledge the important work of The Disinformation Project in Aotearoa.

- Tomorrow: Part 2: WS storytelling in more detail

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.