Rising prices directly impact virtually the entire population, so it’s not surprising that there has been a constant drumbeat of reports in the corporate media laying out the factors contributing to inflation as well as its economic and political consequences. But while the media cite many legitimate factors, including pandemic-induced effects on supply and demand, their choices of which causes to emphasize can have political and economic consequences of their own.

An NBC Nightly News segment (11/12/21) on the “Inflation Crisis” stressed the role of labor shortages.

A FAIR study looking at six months of coverage across six primetime television news shows and NPR‘s All Things Considered found that segments on inflation put far more emphasis on the contributions of labor shortages and social spending—through driving up the cost of labor—than to the role of corporate profit-taking.

This portrays the economy as a zero sum game between workers and consumers, who appear to be intractably at odds if corporate profits are left out of the equation.

During the same period, the shows proved capable of hearing workers’ demands for higher wages when their coverage framed the issue as a “Great Resignation,” or during the shows’ scant coverage of “Striketober,” when a wave of labor militancy swept through much of the country.

This points to an inconsistency in coverage of the same labor market trends: When the shows were covering inflation, the “tight” labor market was mostly treated with the cool and icy calculation of market logic. But on the comparatively rare occasions when the shows covered the grievances of workers and their demands for dignified work—which are widely popular demands, given that most consumers are in fact workers too—the reports showed a more human side to what would otherwise be numbers on a scorecard, and mentioned the record profits of corporations.

Causal arguments

FAIR analyzed the transcripts from ABC World News Tonight, CBS Evening News, CNN’s Situation Room, Fox Special Report, MSNBC’s The Beat, NBC Nightly News and NPR’s All Things Considered between September 2021 and February 2022, using the Nexis news database. We searched for stories mentioning “inflation” and identified 310 segments.

We also searched for segments mentioning “labor,” “union” or “worker.” The labor search terms were meant to identify coverage of worker activism and how it compared to labor market coverage in the context of inflation. The search turned up 73 such segments.

We recorded the main causal arguments identified in inflation segments, grouped into six main categories:

- Supply (“The supply of new cars was limited by that shortage of semiconductors.”—All Things Considered, 1/12/22)

- Demand (“People just said they had more money from not going out and doing stuff last year.”—All Things Considered, 11/26/21)

- Labor shortage (“There aren’t enough truck drivers. So, more containers get stacked up. They don’t get delivered.”—Situation Room, 11/10/21)

- Social spending (“The spending plan could create more inflation to the extent that it’s pumping more dollars into an economy that has a lot of money flowing around in it.”—Fox Special Report, 11/24/21)

- Covid-19 (“The emergence of the Omicron variant poses increased uncertainty for inflation.”—Fox Special Report, 12/22/21)

- Profiteering (“There’s increasing evidence and suspicions that this market power has gone too far and is beginning to hurt consumers.”—All Things Considered, 9/13/21)

These categories were non-exclusive; a suggestion that Covid had caused supply problems, for example, would be counted in both categories. Many segments included more than one causal argument, while 116 attributed inflation to no cause in particular.

We don’t talk about profit-taking

Of the 310 segments that covered inflation, eight identified profiteering as a causal factor, while 50 put the focus on workers, either in the form of labor shortage or supply-side social spending arguments (the latter being a proxy for the former). While labor market trends have had an inflationary impact, the disproportionate focus on them, without mention of the underlying conditions that lead to labor shortages in the first place, erases the culpability of corporations. And as economist Dean Baker (Beat the Press, 11/10/21) explained, it would be a “perverse” solution to inflation to put “downward pressure on wages” by increasing unemployment, when companies are already incentivized to “innovate to get around bottlenecks…in ways that could lead to lasting productivity gains.”

A report by Jacob Ward (NBC Nightly News, 1/22/22) was one of the only segments that looked at how corporate consolidation contributed to rising prices.

An NBC Nightly News investigation by Jacob Ward (1/22/22) was one of the only segments that focused on the inflationary impact of market consolidation. Tyson, Cargill, JBS and National Beef, Ward reported, “control roughly 85% of all beef production in America, and saw their profits tripled during the pandemic.” Other references to the meat trusts were limited to Joe Biden’s plan to apply pressure to meatpackers and Tyson’s decision to raise prices due to “escalating costs” (NBC Nightly News, 12/10/21, 11/15/21). This angle was absent when it came to other powerful industries, however.

David Dayen and Rakeen Mabud of the American Prospect (1/31/22; CounterSpin, 2/11/22) raked through company earnings calls and CEO statements, and found ample evidence for profit-taking in the direct accounts of numerous retail executives:

Corporate profit margins are at their highest level in 70 years, and CEOs cannot help but tout in earnings calls how they have taken advantage of the media commotion around inflation to boost profits. “A little bit of inflation is always good in our business,” the CEO of Kroger said last June. “What we are very good at is pricing,” the CEO of Colgate-Palmolive added in October. Inflation is being enhanced by exploitation, with companies seeing a “once-in-a-generation opportunity” to raise prices.

Corporations with no choice

CBS News (11/10/21) made a small business owner the face of corporate America: “If they’re charging me, I have to turn around and charge my customers.”

Despite this, the decision to raise prices was often reported from the perspective of small business owners. Five such segments appeared across CBS Evening News, including a Houston boutique owner (11/10/21) lamenting that she hates having to raise prices, but that “if they’re charging me, I have to turn around and charge my customers.”

One of the segments that directly addressed the decision from the perspective of multinationals appeared on ABC World News Tonight (10/22/21), where Gio Benitez reported:

Major companies facing rising costs now expecting to charge more, like Nestle, the world’s largest food and beverage company; Unilever, maker of Dove soap and Ben & Jerry’s; Procter & Gamble, from grooming products to diapers; and Danone, maker of yogurts and plant-based milks, even Evian water. Inflation shooting up by 5.4% in just a year. That supply chain crisis is taking center stage.

The profitability and market dominance of these firms, especially Nestle and Procter & Gamble, made no appearance—with price hikes instead attributed to corporations “facing rising costs.”

Despite this framework, recent polling from Data for Progress suggests that Americans aren’t buying it, with only 29% of respondents believing that corporations had no choice but to price-gouge. And with $19 billion being paid out to Procter & Gamble shareholders in the wake of a 14% rise in the cost of diapers, that skepticism is hardly surprising.

Ari Melber of MSNBC’s The Beat (1/11/22) covered inflation’s disproportionate impact on workers, even citing the “Great Resignation” as a factor in labor shortages, but did not mention monopolistic corporations’ price-gouging. Melber pointed out that it is average workers who “bear the risk in our version of capitalism,” as opposed to “pandemic billionaires.” He described this disproportionate impact as “classism.” The omission of the evidence for price-gouging was all the more stark in the context of reporting that ostensibly focused on the interest of workers.

Slamming social spending

Despite the mounting evidence that corporate greed plays a significant role in rising prices, the shows tended to focus on social spending as a possible factor, with 67 segments framing debates around both whether the already-passed stimulus bills were responsible for current inflation, and whether Build Back Better would worsen it.

These debates centered around both supply-side and demand-side factors. On the supply-side, the debate was whether social spending was keeping Americans from seeking work, given that the stimulus provided an alternative form of income. This in turn fueled the labor shortage and strengthened workers’ hands, the argument went, contributing to the rising cost of labor and the shortage of goods. It follows that businesses had no choice but to pass these rising costs onto consumers.

Washington Post opinion writer Charles Lane went on Fox‘s Special Report (10/8/21) to share his view that redistribution will slow job growth and increase inflation: “Two bills of spending that are more than $4 trillion. And we’re going to pretend that this is going to have no effect on jobs? No effect on inflation?”

While other networks proved more willing to provide an alternative view when discussing social spending as a possible inflationary cause, they rarely outright refuted the claim, let alone touched on corporate profits.

NBC News (11/12/21) cited Rep. Jim Jordan (via Fox News): “Their plan is basically, lock down the economy, spend like crazy, pay people not to work.”

Kristen Welker (NBC Nightly News, 11/12/21) reported that although Biden was

insisting that while more spending generally drives prices up, his trillion dollars bipartisan infrastructure bill will bring prices down long term…. Moderate Democrat Joe Manchin suggest[ed] the president’s spending bills could raise prices even more.

And Republicans were “blasting the president’s policies.” The report cut to Rep. Jim Jordan (R.–Ohio), who claim ed, “Their plan is basically, lock down the economy, spend like crazy, pay people not to work.”

To center debates over inflationary causes around redistributive measures, while failing to bring up the stacks of cash lining the pockets of the very corporations raising prices, leaves an impression of scarcity and implies a necessary struggle between workers and consumers. It also ignores the reality that countries like France and Japan, which had larger stimulus packages, actually saw less inflation.

Not only do supply-side social spending arguments blame labor for rising costs, they do so by claiming that workers have it too good. Redistributive measures can’t work, they presume, because if labor is not desperate enough to seek alienated, low-wage jobs, the economy will grind to a halt. Something has to give, and it won’t be the billionaires who happen to own the media outlets.

On the demand side, opponents of social spending argued that the stimulus put far too much disposable income in the hands of ordinary people, whose spending therefore outpaced supply. To argue that there is too much money in the hands of regular people, in light of more than a decade of quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve—transferring wealth to the very wealthy to prop up stock markets—brings to mind Martin Luther King’s statement that this country has “socialism for the rich, and rugged individualism for the poor.”

Inconsistent labor reporting

The six-month timeframe coincided with both “Striketober” and the “Great Resignation,” moments that together saw workers utilizing their temporarily enhanced bargaining power. While union membership is at a historic low, support for unions is at the highest it’s been since 1965. According to Cornell University’s Labor Action Tracker, there were 442 strikes and labor protests between September and February–likely an undercount, given the rise in strike activity not sanctioned by unions.

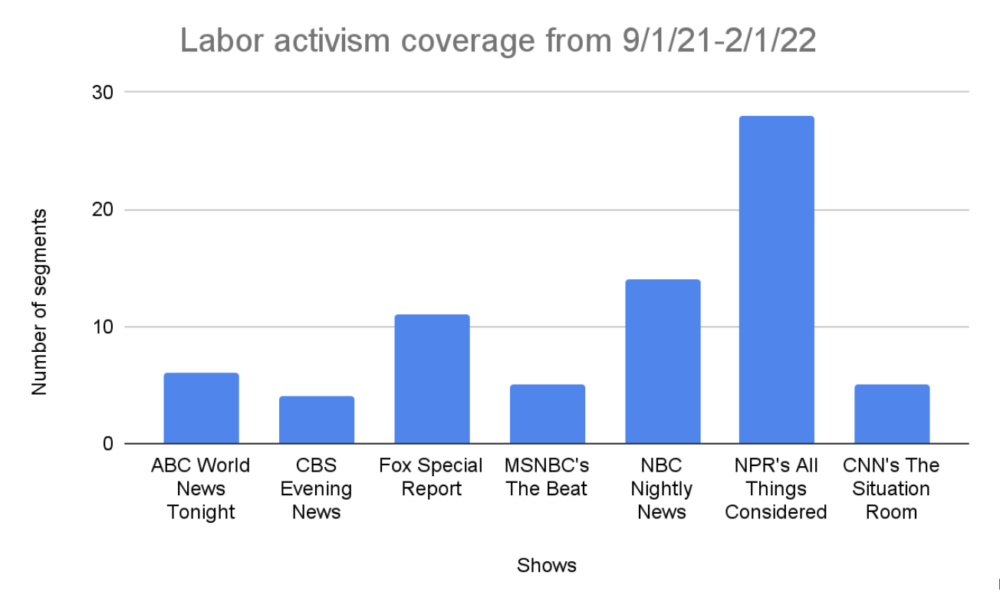

FAIR found that NPR’s All Things Considered included 28 segments on labor activism, but the remaining shows had at most half that amount. NBC Nightly News came in second place, with 14 activism segments, while Fox Special Report had 11, ABC’s World News Tonight had six, MSNBC’s The Beat and CNN’s Situation Room had five, and CBS Evening News had four.

While the coverage of strikes proved some shows were capable of hearing the concerns of workers bargaining collectively, the focus on labor shortages in inflation reporting highlighted a disregard for the perspective of labor.

When reporting on the John Deere strike that saw more than 10,000 workers walk off the job, Charlie De Mar (CBS Evening News, 10/14/21) noted that it came “as the company is forecasting its best earnings ever”; he listed workers’ demands, including “livable hours and benefits.”

CBS Evening News (12/10/21) noted that “a shortage of truck drivers to deliver the goods.” contributed to inflation—but didn’t mention the conditions causes truckers to leave the business.

However, in the show’s segments that attributed inflation to labor market trends, workers’ grievances were mostly left out of the picture. Carter Evans (CBS Evening News, 12/10/21) reported that the rising costs of “just about everything,” from beef prices up by 50% to fuel prices up by 53%, were the result of soaring demand, while the supply chain was hampered by “a shortage of truck drivers to deliver the goods.” Never mind the evidence of price-fixing in a meatpacking industry fraught with consolidation, or the poor labor conditions driving people to resign from trucking.

CBS‘s Scott McFarlane (1/12/22) reported that “a survey by an association of the nation’s grocery stores finds 80% of them are having trouble recruiting or retaining workers right now,” citing this as evidence that labor shortages were a factor in empty grocery shelves and higher prices. McFarlane neglected to mention the low wages and safety concerns that prompted more than 8,000 Kroger grocery workers in Denver to go on strike that very morning (Wall Street Journal, 1/12/22).

Claims of a trucker shortage received the most emphasis, appearing in 13 unique segments across all shows. ABC‘s Whit Johnson (10/13/21) included “not enough truck drivers” among a list of inflationary pressure points. Fox News chief correspondent Jonathan Hunt (10/8/21) claimed that “supply and demand is not the problem…. There simply aren’t enough truck drivers to get goods to American store shelves.” News flash: If there aren’t enough drivers, that’s a supply problem.

While primetime audiences were made well aware of how few truck drivers are on the highways, they were left in the dark about how trucking deregulation has led to stagnant wages and lack of driver protections (American Prospect, 2/7/22). Segments reporting on ports remaining open 24/7 to alleviate backlogs (NBC Nightly News, 10/13/21) made no mention of the stolen wages and general precariousness of the labor making that happen.

Fickle supply chain

While there were multiple mentions of “supply chain bottlenecks” across the seven shows, the decades-long transformation of the global supply chain to maximize profits at the expense of its resiliency (CounterSpin, 2/11/22) was generally not a part of the story.

Just three ocean shipping alliances control 80% of the market, giving them substantial power to set prices and squeeze wages. In order to keep down the costs of production and distribution, shipping companies promoted a “just-in-time” delivery schedule, reducing warehouse costs but also raising the chances of disruptive shortages. Coupled with the outsourcing of manufacturing, just-in-time delivery supply chain “shocks” are less shocking than they might appear.

But according to Fox News correspondent Jacqui Heinrich (11/24/21), the White House’s accusations of price-gouging by the ocean shipping cartel as a driver of inflation were “ominous,” as they indicated that supply chain crises may take years to resolve. Not once did she mention the cartel in question made nearly $80 billion in the first three quarters of 2021, giving the companies ample and unaccountable price-setting capabilities (American Prospect, 1/31/22).

News media that feature constant coverage of inflation may appear to be serving the public interest, but with an issue that directly affects so many peoples’ wallets, it’s important that the corporate media give an accurate portrayal of the contributing factors. And while sympathetic coverage of labor activism may seem pro-worker, that’s undercut when the debate about what’s making it harder for people to put food on the table is centered around low-wage essential workers saying enough is enough.

The post Blaming Workers, Hiding Profits in Primetime Inflation Coverage appeared first on FAIR.

This post was originally published on FAIR.