You create work about your father, Rodney Barnette, from the founding of the Compton chapter of the Black Panther Party, to the creation of the first Black-owned gay bar in San Francisco, The New Eagle Creek Saloon. Can you talk about when and how you first realized you wanted to make work about your family’s history?

As I often say, my dad is the youngest of 11 children and I was the last born of his generation, so I’ve always been the young one in the room observing and fascinated by my family’s history. I am also the one behind a camera or trying to jot things down to remember later. I think that’s always been my role in the family or my way of participating in the world.

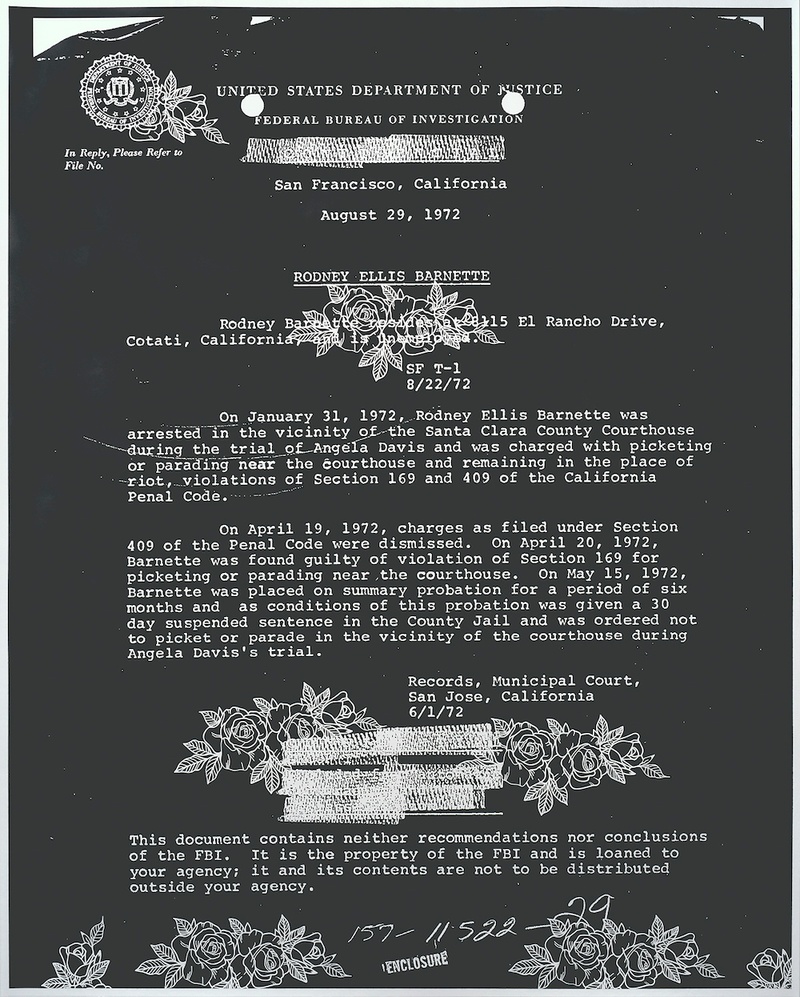

But what really formalized what felt like my responsibility or inheritance was when I received the FBI dossier on my father. [Rodney Barnette’s 500-page surveillance file amassed during his time organizing with the Black Panther Party and helping Angela Davis in her fight for exoneration serve as source material for some of Sadie Barnette’s work.] As a family, we filed a Freedom of Information Act request in 2011. It took almost five years of going back and forth with the FBI to receive this 500-page surveillance file. It was very chilling and infuriating, and at the same time, it forced my father and I to have the kind of conversations that are easy to put off otherwise. That’s when my dad really became a central character in my work.

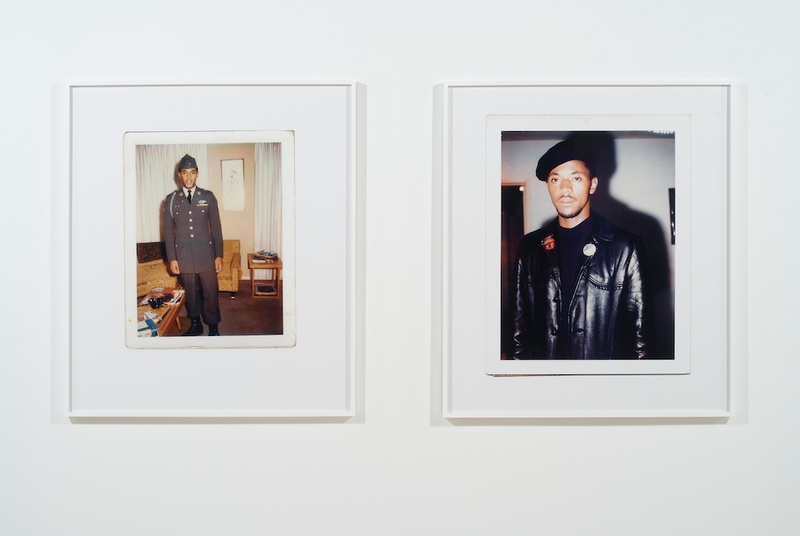

Caption: Untitled (Dad, 1966 and 1968), 2016, Diptych, digital c-print. Photo: John Wilson White. Image Description: Two photographs of Rodney Barnette. In the first image Barnette, a young person, is wearing an army uniform, in the second Barnette is wearing a Black Panther outfit.

Building on that, your work oscillates between intimate and personal, or public and collective. What do you hope your father’s story might bring to our collective understanding of history or how history is constructed?

I’ve always felt like the more specific I could keep my work and story, the more wide open and inviting, and in some ways universal, it is. The more personal it is, the easier it is for other people to locate history personally for themselves. It seems counterintuitive; the more it’s about us, the more it’s for everyone.

It’s also important for me to tell the stories that I know best. I try to stay focused on what feels like it’s mine to tell. And then hope that it will relate to other people, to wider histories, and on an emotional human level, beyond even the history of the Black Power Movement or any of the social structures that we’re living under.

There are always parts of the work that just connect us to what it means to be alive, and what it means to be a spirit in a human body, and what it means to be on this planet hurtling through space. By talking about these really specific things, it’s also leaving room for really abstract, existential quandaries or those big questions.

Caption: FBI Drawings: Picketing or Parading, 2021, powdered graphite on paper. Image Description: A black and white drawing of an FBI document charging Rodney Barnette with picketing or parading outside of a courthouse during Angela Davis’s 1972 trail. Sadie Barnette has redacted some of the information and drawn flowers on the document.

It’s so interesting to think about how many different stories and timelines we touch on in our lifetime.

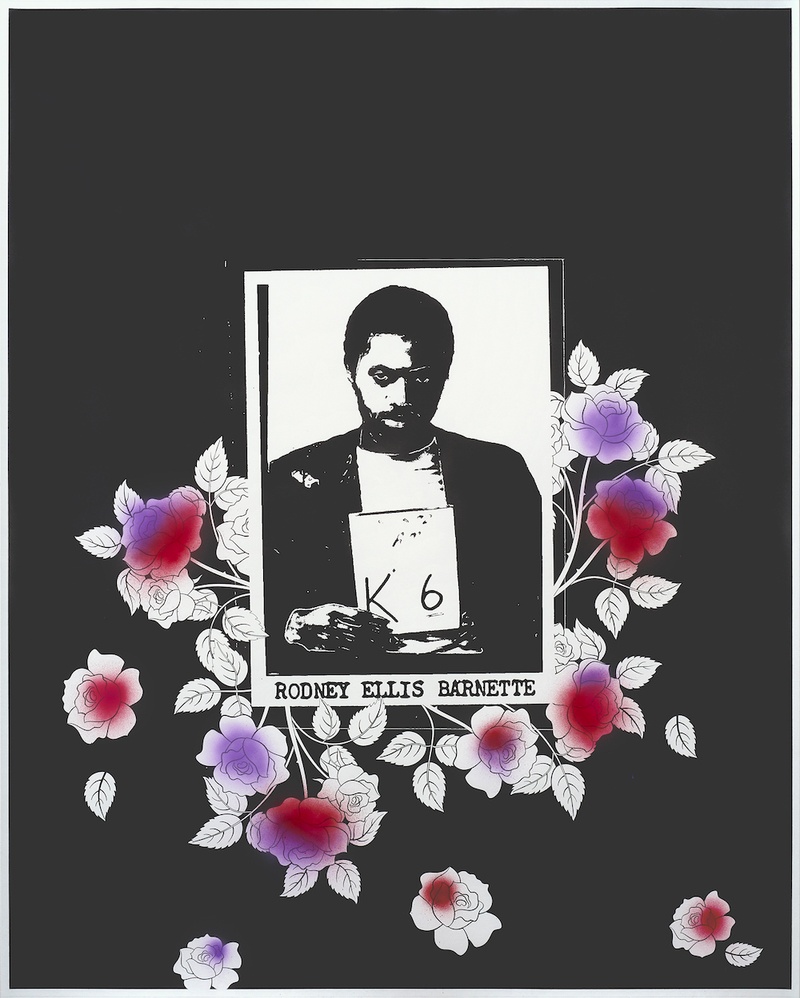

Definitely, and how many stories are forgotten or how many stories someone has and you have no idea. One of the main reasons I wanted to tell my dad’s stories was because he wasn’t a famous or well-known person, even though it sounds like he would be based on how extraordinary his life is. So many people have these extraordinary lives that there’s no documentaries about, and no one knows about.

When I tell people my father founded the Compton chapter of the Black Panthers, they would ask, “What’s his name?.” They would expect to have heard of him in their history books. He was just a regular person. But that is true of so many people who are our uncles, teachers, whoever, who have intersected with all of these amazing moments in history. It is regular people who make history and then a few names get remembered and written about. I guess my work is also a way of de-centering this idea of the famous leader, these are families and regular people.

Caption: FBI Drawings: Mug Shot, 2021, powdered graphite and spray paint on paper. Image Description: A black and white drawing of Rodney Barnette’s mugshot. Sadie Barnette has drawn red and purple flowers around the image.

What are some key ideas to keep in mind when creating a work that is personal and about someone else’s life, even if it’s somebody who you know intimately?

If anybody is considering stories within their family, do not hesitate or put off recording the interviews or asking your family members questions. I think sometimes it feels invasive or awkward, but people usually want to share their stories and are happy to be seen in that way. Just go for it, just take out your phone and record.

How does being an artist and personally related to these stories allow you to engage differently than a historian or archivist? And, in your opinion, what is the role of artists in questioning public memory?

The way I move through the world and know how to make sense or find meaning in things is through making artwork. Because of the slipperiness that it allows, the contradictions that it’s able to hold, and because of the emotional registrar that is available .

I don’t think of artists as having more or less responsibility than anybody else. It seems like you can do that job in many different ways, whether it’s to critique or entertain or make money. For me, I’m thinking humbly about honoring and paying dues towards an inheritance of a history that has brought me to where I am. There’s just so many people, ancestors, and artists, and I move through the world in a way that would be unimaginable without them.

Caption: Installation view of Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon, The Kitchen, New York, January 18, 2022–March 5, 2022 Photo: Adam Reich. Image Description: A fluorescent pink and glittery u-shaped bar with bar stools and a neon sign that reads EAGLE CREEK.

Thinking about creatively re-examining the past, your work seems to bend space and time so that the public can experience the essence of a past moment in the present. For example, for The New Eagle Creek Saloon [Barnette’s reimagining of the first Black-owned gay bar in San Francisco, owned by her father, which offered a safe space for the multiracial queer community], you reimagine your father’s bar, but it’s a recreation through your eyes and not a historically accurate representation. Can you talk about this approach or translation?

Early on it was a practical matter, in that I didn’t have a lot of documentation of what his bar looked like. I also realized that it was more important to make it feel how it felt, rather than look how it looked. For example, I didn’t want it to be reverent or quiet. I didn’t want my project to exist on walls, but instead to be in the center of any space and feel more like a beacon that’s drawing you into a central light within a space.

I wanted it to feel alive. To me that felt like the best way of honoring something that was so dynamic, by making something that would facilitate new connections, joking and dancing, and all of the texture of what the original bar was like.

I also noticed that it was important for my voice to be there. I think the spirit of the Eagle Creek would want me to put my artistic aesthetic at the forefront, because it wants everybody to dress the way they want and show up in the way they want.

I dialed up my perspective and authorship in the piece as well. In order for people to feel really cute and flirtatious and be excited to be in a space, I felt like it needed to be pink, holographic, and very aesthetically pleasing. And also look a bit contemporary so that it felt like it was rebranded for today because that would make it feel as hip as it felt then.

Caption: Tygapaw DJing at Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon, The Kitchen, New York, March 5, 2022. Image Description: An image of the same bar with a DJ, DJ equipment, and smoke coming from a smoke machine.

With both The New Eagle Creek Saloon and The FBI Project in mind, can you talk about why it’s important to look back from the present moment?

It’s about looking back as a way of trying to understand where we could go and as a way of honoring those who have tried to change the world in big and small ways. I am paying tribute to the ways in which my father showed up with so much belief and hope and really tried to change things. It’s a meditation on people who dared to believe and then hopefully making space for future dreaming and daring. It seems like a beautiful way to move through life, thinking about how to make it better for more people.

This work is always relevant, even when you wish it wasn’t. Thinking about the The FBI Project, which at so many points coincided with developments around the surveillance of Black Lives Matter activists and the expansion of digital surveillance capabilities. All these things are still maddeningly relevant.

Caption: Installation view of Sadie Barnette: Inheritance, Jessica Silverman, San Francisco, November 20, 2021–January 8, 2022. Photo: John Wilson White. Image Description: A large, shiny, silver holographic couch with pink and purple glittery speakers on either side. A large black and white photograph of a woman reclining on a coach is hung above the couch on a wall with black and white wallpaper.

Totally and with that in mind, what do you see as the goal of your work?

I guess there’s the personal part of it, which is that it often keeps me from just spiraling off the face of the earth, to have something to focus on and to show up for. To know that I can’t do everything but I can make this one drawing. This one drawing isn’t going to undo state surveillance, but something is going to happen through making it that’s worth sitting down and showing up for.

To define what’s successful: I would say, when the work creates enough of a parameter that people are having an experience that isn’t all over the place, but at the same time the parameters are loose enough that people are having experiences that I didn’t necessarily think about or intend. So it’s directed but not didactic.

Also when other people see themselves in the work. When people are like, oh, this feels like my family or I recognize this living room or this kitchen, to me that feels like a successful reflection.

The Eagle Creek project feels successful when everyone forgets that they’re at an art installation and it just feels like a party. And you get that high that you get from dancing when you just get out of your own head, and get out of your own way and are just in this collective groove. I want there to be some generosity, or even seductiveness, where you want to be there and then you’re figuring out why or what it means.

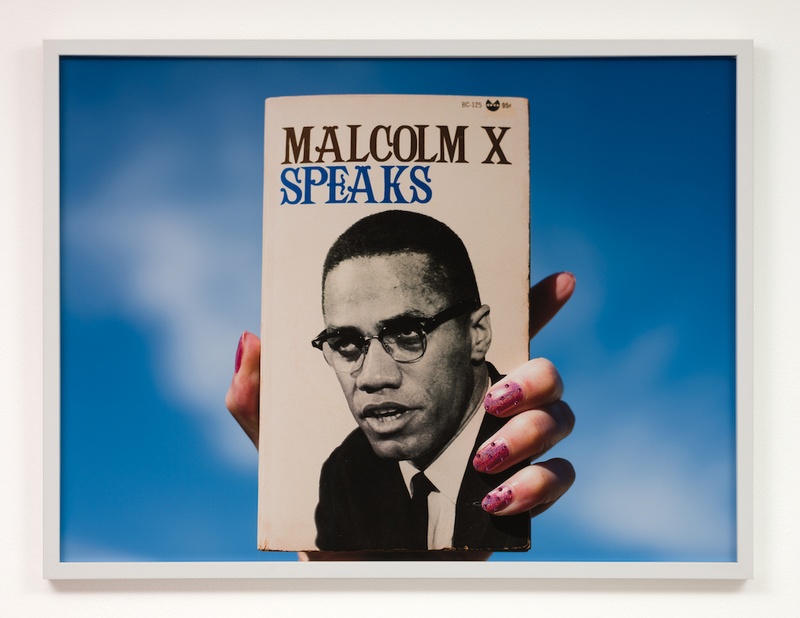

Caption: Malcolm X Speaks, 2018, archival pigment print and rhinestones. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio. Image Description: A photograph of a hand with pink glittery, studded nails holding a book with a black and white image of Malcom X with a title that reads MALCOM X SPEAKS.

Building on that, your work deals with heavy subject matter from surveillance to homophobia, and racism, but you’re always centering joy, through color, glitter and by creating welcoming spaces. Can you talk about why joy is so important?

For me it goes back to my family and seeing that even as all of these really repressive structures are imposing themselves in people’s daily lives, it doesn’t mean that people were waiting for the perfect world in order to be their full selves…in order to wear their best outfit or to sing their best song, or cook their best meal. There’s something about both looking critically at the world, but also enjoying your life, and how we take care and show up for each other. And just how beautiful and cool people can manage to be, even in the face of adversity and dire circumstances or racism or the prison-industrial complex. It never took away from the magic and poetry of my family and Black creativity in this country.

Sadie Barnette Recommends:

Amy Goodman’s Democracy Now

Ruth Ozeki’s The Book of Form and Emptiness

Sister friends

This post was originally published on The Creative Independent.