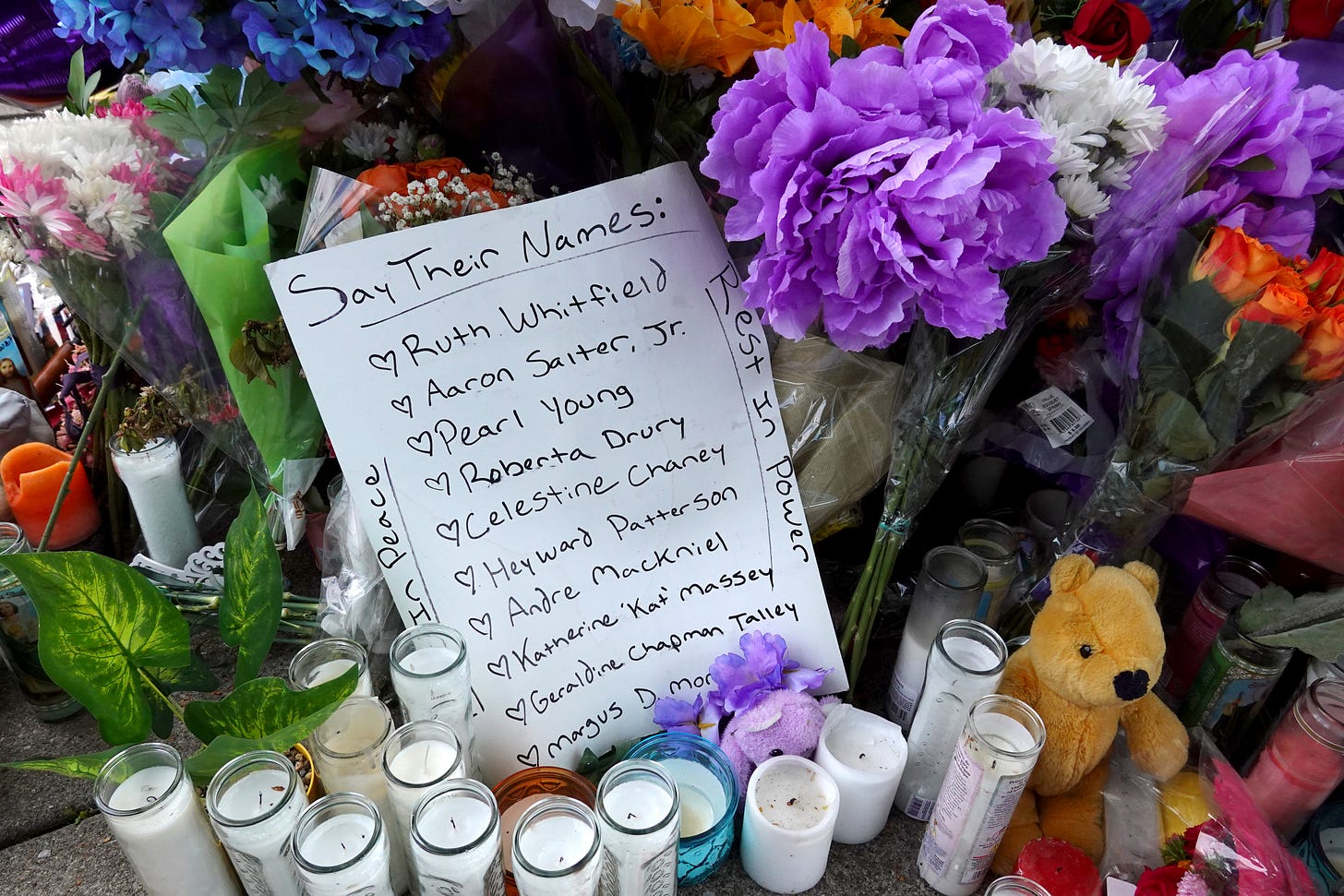

This is not who we are. It is always tempting to frame episodes like the racist massacre in Buffalo as the exception to the rule. It is harder to acknowledge what the overwhelming record makes plain. This is precisely who we are.

America has a greater-than-average propensity toward violence, especially racist violence. And while the idea of violence as an American tradition isn’t a truth one often hears from political leaders, who have to, you know, win votes, it is a truth that Senator Chris Murphy, Democrat of Connecticut, has articulated with great force.

“The Buffalo shooter’s manifesto is a tribute to this tradition,” Murphy said on the Senate floor this week. “We can look into the flames of American violence, this fire that’s been burning since our inception, and we can choose to douse the fire or we can choose to continue to pour fuel on top of it.”

The barbarism in Buffalo called to mind a conversation I had with Murphy some time ago about his book, The Violence Inside Us, and I am excerpting it for you below.

This post is free and open to all. Putting out this newsletter takes labor and care, and it really helps if you are able to become a supporting subscriber and patron.

You write in the book that humans are the most violent of mammals, and Americans are the most violent of humans among comparable rich countries.

You offer a provocative and, I think, correct assessment of one of the main reasons why: anti-Black racism. Can you explain why that has given America a special propensity toward violence?

I think it’s interesting that, as violent as America is around the revolution, we don’t start to become a global outlier of violence until the slave population explodes. There’s a ton of violence in America in the 1600s and 1700s, but from the data we can glean, it looks like America’s homicide rate doesn’t start to go into the stratosphere until we have so many enslaved Americans that violence is the defining feature of the American economy.

To me, violence explains a lot about how America has ordered itself from the very beginning. But, for many of our formative years after the Constitution’s signing until the eradication of slavery, it took just massive, mind-numbing amounts of violence to keep America’s economy running. It stands to reason that we became anesthetized to that violence during that period. I don’t think that we’ve ever got our sense of feeling back.

In that sense, violence was not a bug in the operating system. It was a feature if that was the kind of economy you wanted.

We decided to take a shortcut to economic prominence. We decided to use epidemic levels of violence to enslave an entire race of people to create cheap goods that we could send worldwide. It was a choice we made, but the choice required us to brutally subjugate millions of people in this country. It ended up making violence an acceptable mechanism to maintain economic and social order.

It’s no coincidence that, during the 1800s, white-on-white violence was dramatically elevated, especially in the South, because it just became a much more normal course of behavior once you were using it so regularly against slaves.

As more and more Americans are taught a more honest version of American history, it in a way becomes harder for people like you who run for office to tell a true story, and to tell a story that inspires people and lifts people up. I wonder how you think about this twin obligation — to tell a true and dark and blood-at-the-root story of America, and yet not be a Debbie Downer whom no one wants to vote for.

This reckoning we’re having with our past is necessary, but it also comes with real consequences for one of the few threads of fabric that unites the country. As we all retreat to our corners, as we all get our information from different sources with different spins, our founding ideals and founding mythology are among the few things that we have left in common. Now, we’re not even sure what that mythology is.

Here’s how I think about it. Notwithstanding the fact that there was an enormous amount of violence necessary to stand up the American economy in the late 1700s, and notwithstanding the fact that most of our founding fathers were part of that slave economy, their ideas were nonetheless revolutionary. The developing idea of America, as we brought in people from all sorts of different places in the world, is no less revolutionary.

I think we can acknowledge the unconscionable flaws at America’s founding while still recognizing that these two ideas — a government based upon the self-determination of a people, and a multicultural society in which everybody gets to be an American but also retain part of their heritage — those are off-the-wall ideas. We should accept that we are always in the process of getting better and getting closer to actually realizing them.

In the book, you link the special propensity for violence in America to our heterogeneity and how it intersects with in-built human tribalism. As America becomes a majority-minority country in the ensuing decades, if we don’t do some of the big course-changing things that you advocate for in the book, would you expect us to become more rather than less violent?

The data show that violence tends to increase when you have large numbers of new entrants to America competing for scarce economic space. That makes sense, given that overall violence does tend to track poverty. As this one man told me on the streets of Baltimore, “Hunger, it hardens your heart.”

To the extent that white Americans are still the dominant power class in this country, as there become more non-whites and more threats to the white hierarchy, it stands to reason that there will likely be more chances for violent outbreaks. That means it’s incumbent upon us to reduce the number of firearms and reduce the chances of police brutality so that there are fewer mechanisms by which to allow in-groups to perpetuate violence against out-groups.

It also means that we’ve got to be serious about creating less economic scarcity. If our history tells us that economic scarcity can lead to violence, then let’s create a system in which more people can access economic success.

Chris Murphy is a Democratic senator from Connecticut. He is the author of “The Violence Inside Us: A Brief History of an Ongoing American Tragedy.”

You can read my full conversation with Senator Murphy here:

This post was originally published on The.Ink.