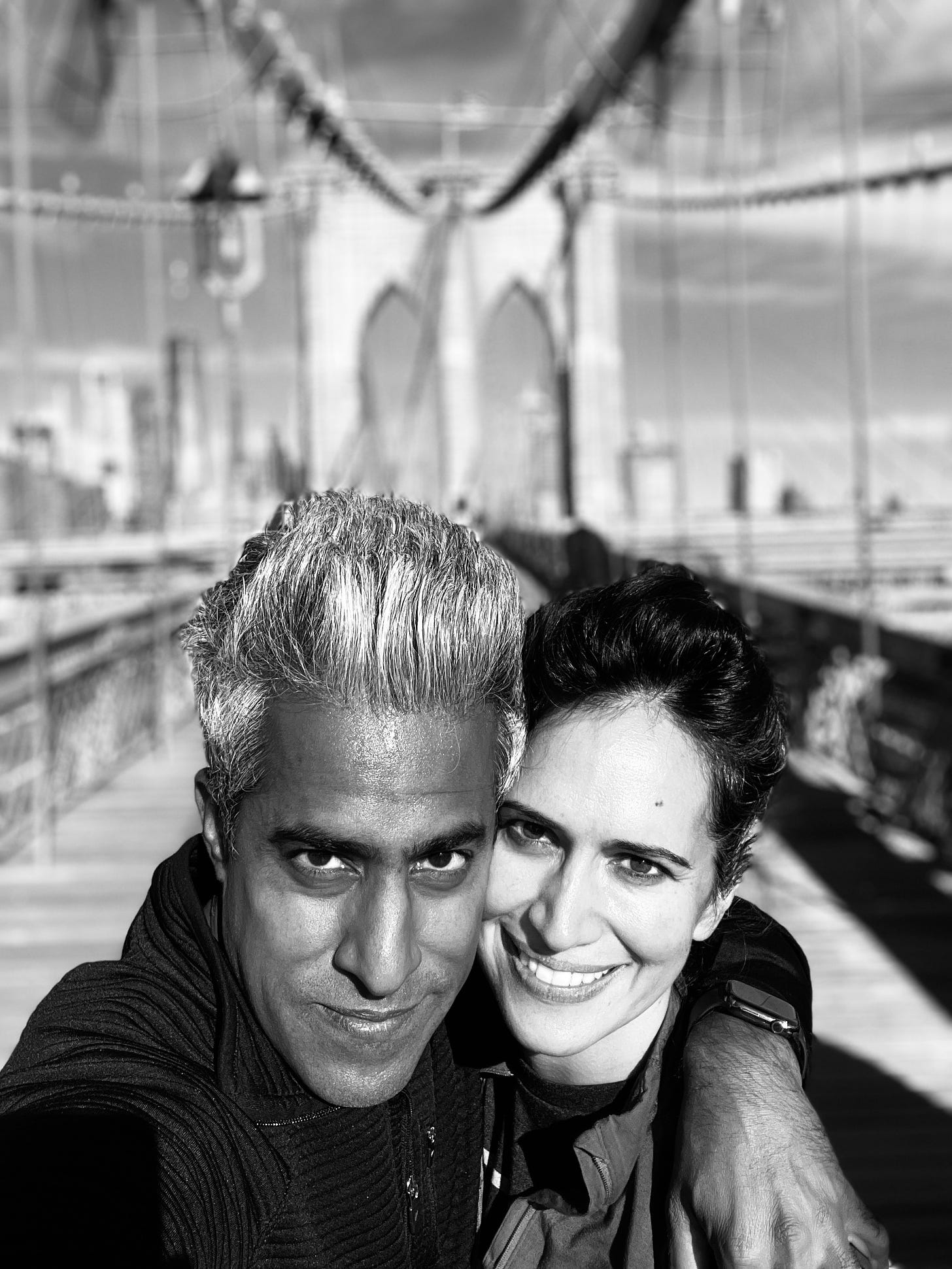

So today is my birthday. I’m 41, a confirmed geriatric millennial. I marked the morning by going for a long (for me) run with my wife, Priya, that started in Brooklyn and took us over the Brooklyn Bridge and down into Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we annulled the run with a greasy brunch.

One of the many blessings I count this year is this Ink community we are building. Having you as readers and fellow explorers in this strange time is a great gift.

By the way, if you have a piece of life advice for the sunset years ahead, drop it in the comments section below.

Today I have something funny and strange and whimsical for you, below the jump. It’s a slice of a new horror novel that takes on marriage, in-laws, depression, and ghosts.

But before that, I wanted to tell you about a new book-discovery platform that I’m really excited about. It’s called Tertulia, and it’s attempting to be a place where people can find book recommendations from real human beings, not just algorithms.

I asked the good folks at Tertulia if they would offer a special enticement for Ink readers to hop over and check out the app. And they did. From now through October 18, subscribers to The Ink can get my new book that I’ve told you about, The Persuaders, for only $10 in the app! That is $20 off.

If you want to get yourself this birthday present on my behalf, first download Tertulia for iPhone in the app store. After you set up your account, you can add The Persuaders to your cart in the app and use promo code INK at check-out to apply your discount. (For any questions, contact hello@tertulia.com.)

Onward!

Oh, I should mention that if you’re interested in an essay by me in a less serious vein than the usual, check out my debut humor essay in The New Yorker this weekend.

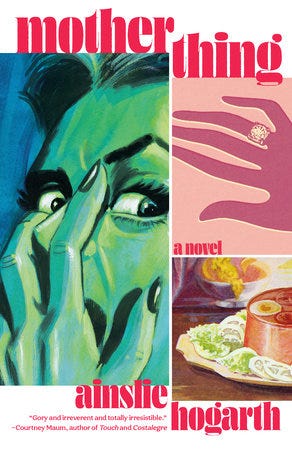

Now, to the main attraction. Ainslie Hogarth’s new book, Motherthing, came out today. And it’s a work of fiction that is a darkly funny take on family and death…and food.

Enjoy!

A hilarious dinner

By Ainslie Hogarth

I feel good after being at work, more like myself. For the first time since Ralph’s mother died. I stop at the grocery store and fill two reusable shopping bags with everything I need for a very hilarious dinner. I believe we should all use reusable shopping bags. So does Ralph. His mother has a collection of plastic bags that date back to when plastic was invented. They’re pressed into a drawer in the pantry, a nearly solid brick of them. Sometimes when you pull one out, the rest of them crackle together for longer than you’d expect, like a ritual: when one is pulled, they must all sing the crackling songs of their ancestors.

I stick my key in the door, look up at the house, see a second-floor curtain shudder, surprised that Ralph is home already. Up there, in his mother’s room, pinching the curtains shut, even though it’s dark outside.

I want to sell the house right now, use the money to escape the city, move into a cottage way up north and fill it with squealing, jabbering babies. Babies everywhere: hiding in cupboards and cookie jars and under my skirt, sleeping, limbs limp and dangling over the crooked arms of a tree; floating faceup in the lake, shooting grand archways of water from their mouths for the other babies to paddle through.

I look down into my shopping bags. I know that I have to start cooking this hilarious dinner now, right now, otherwise we’ll be eating later than either of us likes to. I say either of us, but I also know that Ralph won’t care if we eat dinner at all.

Hilarious dinner: jellied salmon with crackers.

What you do is you soak gelatin in cold water, then you heat it up till the gelatin is all dissolved, then you add canned salmon and salad dressing. I’m going to use ranch because I think it has the right flavor for fish, the closest to tartar sauce. You mix it all together and you pour it into a mold. I have a mold that’s shaped like a fish, which I think is funny and I hope that Ralph thinks it’s funny too.

I toss my keys onto the table. They slide into Ralph’s wallet and phone. I shake off my bag and coat and boots, lean against the banister, holler up to the second floor, “Ralph?”

He doesn’t answer me, so I go up, tap on his mother’s bedroom door. “Ralph?” I crack it open, just a bit, lean across the threshold. “Ralph?”

It’s empty. Totally undisturbed from this morning. Magazines and tissues and water glasses all in the same place they’d been before. Ralph’s impression in the sheets, somehow bathed in winter moonlight through wide-open curtains, which is impossible because they’d been closed just a minute ago, I watched him myself from the front porch, squeezing them shut the way his mother did. Exactly the way his mother did.

No, no, no.

I march over and shut the curtains tight, pinch them down the middle the way that Ralph and Laura do, and I’m surprised to find it offers a kind of unwholesome relief that I have to shake out of my arms like pins and needles.

It’s too dark in here now, my eyes too wide, achieving nothing. I pull the curtains open again, illuminate Laura’s row of lucky charms, troll dolls watching me from the dresser, faces creased with the same ancient wisdom that’s trapped inside newborn babies, destroyed by language, and in the slip of one second to the next my flesh seizes with goose bumps—they know I hate her.

I leave right away, make sure the door is shut behind me.

“He must be up here somewhere,” I mutter out loud, casually, as though a strange thing hasn’t happened, and it works because the things you say out loud like that are powerful. The semi-constant mutterings a wife makes about a husband become the truth: Nothing strange about those curtains being open and Perfectly healthy to sleep all day long!

I check our bedroom and the spare room and the bathroom. They’re all empty too.

I head back down the stairs and along the front hall, lit halfway through by the foyer light but dark at the end where the basement door is. “Ralph?”

I hear whispering. Ralph whispering. From the basement. It’s the sort of scratchy, desperate whispering you’d do if you ever got kidnapped and were trying to secretly get help from a stranger. I can’t make out the words. I try. It’s silent for a minute like he’s letting someone else speak but I can’t hear them.

I place my hand on the table where I tossed my keys, confirm that his phone is here. His phone is here but he’s whispering down there. Whispering now hot and secret again. I want to turn on the lights and say his name, I don’t want to sneak up on him and try to hear more because that’s not what a healthy marriage is all about, but the way he’s whispering, the way that he stopped and then started again, it’s not right.

I follow the sound of his voice, toward the basement door, step around all the creaky spots in the floor. Ralph taught me where they were when we moved in— here’s the bathroom, here’s our bedroom, here’s the kitchen, and here are all the spots in the floor that will make her cry if you step on them. I imagined him as a baby, taking his first steps, wobbling as best he could around the groans and creaks that would alter her mood.

I mimic his tender step, groping along the wall, hear my name jumbled up in his hot whispering. Abigail though, not Abby. I pause, close to the basement door now, hold my breath, waiting for whatever is going to happen next. “Stop,” I hear him hiss, followed by heavy silence, about to burst with something. Awareness. He knows I’m home.

“Abby?” he says. Loud. Abby this time. Abby to me, but not to whoever he was whispering to.

“Oh, yeah! Yep! Hi! I just got in!” I hop back toward the door, planting my feet too hard in all the creakiest spots on the floor, which, after years of fearing their sound, alter Ralph’s mood too. I groan—stupid, careless—and turn on the light, pick up my grocery bags in a hasty attempt to make it seem as though I’d just gotten home. Ralph’s making his way up the steps. He’s been crying. “Oh, Ralphie.” I step toward him.

He flinches. Not because I’m close, but to let me know not to come any closer. “I’m okay.” He smiles but his eyes are glazed cherries and his face is a yanked rag hanging spent from a hook. He heaves what remains of his tears back in through a single nostril, rubs his face from top to bottom with one hand. He’s got the other hand behind his back. Which maybe isn’t a big deal, but I can’t think of him ever looking this way before. Legs spread, not quite blocking the basement door, but sort of. His hand quite conspicuously hidden.

He notices the grocery bags in my hands. “What’s for dinner?” He steps out, closes the basement door behind him with one of his feet. Stands there. Guarding it. I move back a little bit. I’m not scared exactly. Not scared of Ralph, for God’s sake.

“Were you upstairs just now?”

He glances up. “Nope.” He nods toward the basement door. “That there is the basement door.”

“Ha, ha. I thought I saw you up there a few minutes ago. From the porch. You were closing the curtains.”

He gives me a confused look and changes the subject. “You got dinner?”

“Oh yes!” I raise the bags. “I got, well, actually what I got is a lot of work now that I think about it.”

“Well, fuck it then. Do you want to go out?”

“Oh yes, let’s do that. I just have to put these away.” I lift the bags and start toward the kitchen. With his hand behind his back he presses himself against the wall to let me by, careful, I can tell, not to touch me.

It’s weird. And the whispering is weird. And how he’s hiding his hand. But I’m going to ignore it right now, which is easier than it should be, and the musty sleep-smell I catch as I pass him, the off-gas of pajamas becoming skin after too many days and nights unchanged, the truth it reveals, that he didn’t go into work today, I’m going to ignore that too. Because our baby, Cal, is rooting, aren’t you, Cal? Cal is becoming real and she won’t become real in a place where Ralph is dark.

He’s still pressed against the wall when I return. “Where should we go?”

“Aunt Tony’s?” I suggest. It’s actually called Anthony’s, but this one time I called it Aunt Tony’s and Ralph laughed. I thought maybe it would make him laugh again, but it did not.

He just says, “Oh yeah, I could eat there.” He slides along the wall, away from me, toward the front door. He digs one foot into a boot, then the other, struggling a bit without his hand, which is in front of him now, because he’s still hiding it from me.

I don’t want to pry. I won’t pry. A healthy marriage is a trusting marriage. A man’s hand is his own business after all, and I trust him with his own hand business. It’s good to have secrets. Maybe his hand has secretly become a tentacle and that’s fine, I don’t need to know everything for God’s sake, I’m not that kind of wife.

But I should point out that he’s still in his pajamas.

“Ralph.”

He stops and turns around, moves his hand behind his back again.

“Do you want to change?”

He looks at me and kinks an eyebrow, puzzled, then looks down, contemplating his clothes for a long time. Too long. Like he’s trying to understand why I see pajamas and he sees a three-piece suit.

“Yeaaaaaah,” he says slowly. “I should, shouldn’t I.”

I want to smile but can’t quite make it happen because even though I’m trying to be positive, I really, really am, the combination of his pajamas and his hidden hand and his secret whispering is giving me that mounting, dreadful feeling that builds when you’re alone in the dark.

“I didn’t go to work today.” He’s still looking down.

“Oh. Well, that’s okay. You called in sick?”

“No.”

“You just didn’t go in.” He nods.

“Are you feeling okay?”

“Not really.” He looks up and his eyes are all watery again and his hand is at his side now, hung open for me to see that it’s bleeding. A slice across his palm so blood follows the seams, becomes quivering rubies that hang from his fingertips.

“Oh, fuck, what happened to your hand?” I step forward, but he steps back again, looks down.

“I hurt it.”

“I’ll say. How?”

“Let me go change.” He presses his hand against his pajama pants. It’s a lot of blood. It’s going to leave a huge stain where he’s pressed it against his pants. Not that I care about the stain, more so I care that he doesn’t care about the stain. It’s a stain of the tormented, those who really don’t give a fuck anymore, Rorschachs of grease and shit and blood. I see these stains at the old age home, materializing despite every effort, pox-like, on a resident soon to die.

“Are you sure you want to go out? I can make that, that—” I gesture at the kitchen. Jellied salmon, Jesus Christ. It’s morbid and bizarre, something left to rot at a dinner party where everyone has dropped dead at the exact same time. I don’t even know who I was when I thought it might actually cheer him up.

“I’m sure. Let’s get out of the house.”

And then I hear a sound. The tiniest thud. Soft but weighted. Like something boiled. Or jellied. A hunk of my dank salmon, dropping from the height of a table to the floor. It came from the basement. I can’t tell if it’s just a regular sound that basements make, the house’s groaning, harmless guts, or if it’s something else, something down there. I look up at Ralph and he’s staring at the basement door with those round lemur eyes, his hands at his sides now, both of them fists, and a little bit of blood squeezes out, splats silently onto the floor. He rubs his sock over it and moves past me, up the stairs to get changed.

I turn and stare at the closed basement door again. I want to go down there. I want to see what he was doing, why he was whispering. It’s most likely nothing. It’s definitely nothing. This house is always making thuds and creaks and yawns; all those layers of paint and wallpaper, the sticky grime of human fingers and human heat, have made it unstable.

I step toward the basement.

“Don’t go down there.”

I spin around. Ralph’s watching me from the top of the stairs, injured hand held cuplike to hold the blood pooling in his palm.

“Okay,” I say, because I don’t know what else to say. He stares at me until he’s sure I won’t move toward the basement again, and I won’t, because it’s nothing anyway. There’s nothing down there. And I’ve gotta be on tonight, I’ve got to be as much like myself as I can be. Pretend everything is fine and save your family. Normal Abby, normal, normal, like a lighthouse of normalness so that normal Ralph can see it and steer back toward it. Come closer to me, Ralphie, because right now you’re not all the way well. You’re halfway in the dark, seeing the light but not able to reach it, and it’s my job to bring you back.

Ainslie Hogarth is the author of the YA novels “The Lonely” and “The Boy Meets Girl Massacre (Annotated).” This essay was adapted from “Motherthing,” which was published today by Vintage Books. Copyright © 2022 Ainslie Hogarth.

This post was originally published on The.Ink.