(Photo by Matthew Henry / Burst)

Arlo Washington just needed a haircut. Little did he know, when he first picked up that broom to sweep the barbershop floors in exchange for a haircut he couldn’t otherwise afford, it would launch him on a journey that led him to charter the first new credit union in Arkansas since 1996 — People Trust Community Federal Credit Union, charter #24940, approval date Sept. 16, 2022.

“The owner of the shop Royale, he was so comical, and he always had a connection with everybody who walks through the door, and everybody loved him,” Washington recalls. “I watched this colorful character make piles of money and have such an influence on the community. It was from that point on that I said, ‘Man, you know what? This barbering ain’t so bad, you know, if all else fails, I’m going to barber school.’”

After Washington’s single mother died of cancer in 1995, he tried out all else first. He moved to New York and briefly worked as a fashion model and a barber. But times were rough. He spent some nights sleeping in the barber shop or just walking around all night till the sun came up, thinking about how to support his two younger sisters back home. He eventually went back to Little Rock and enrolled in college. He managed to use some of the proceeds from his student loans to open his first barbershop.

“I was thinking, well, if I’m using it, then I’m gonna stay in school and I need to generate some income,” Washington says. “I figured I’d use the student loan to set up my first barbershop. That was 20 years ago. It was usually a lot easier to do. Back then you could set up a barber shop for about five grand.”

Washington’s reputation as a barber grew quickly. One barbershop became two, then three, and eventually seven barbershops and his own barber college.

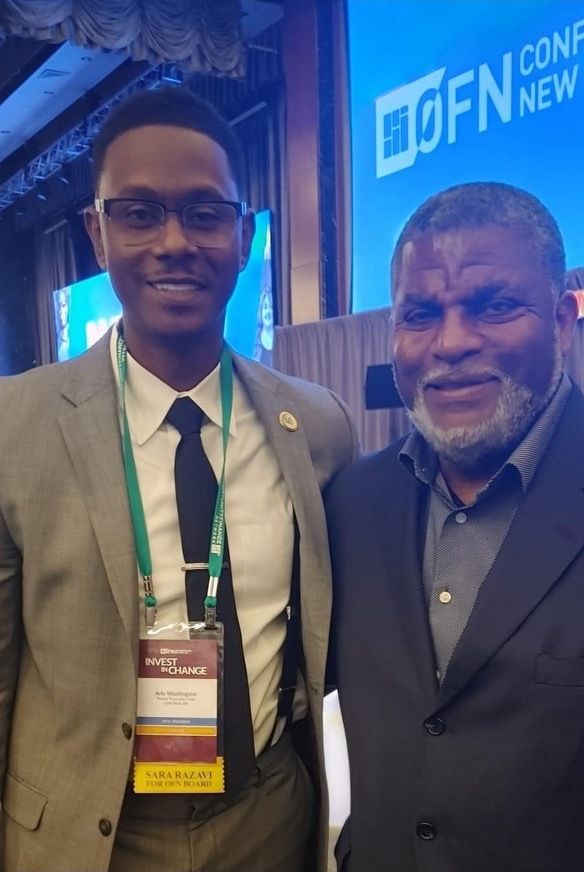

Barber-turned-banker Arlo Washington, left, with HOPE Credit Union CEO Bill Bynum. (Courtesy photo)

Meanwhile, in 2009, the last payday lending storefront in Arkansas closed for business after a statewide ban went into effect. Washington remembers a lot of folks started coming to one of the few places where they knew someone could get a loan that wasn’t predatory — in some cases their barber, in some cases the local barber college.

“We had a sign on the side of the college that said financial aid is available to those who qualify,” Washington says. “So people started coming to the barber school asking for loans.” He understandably had questions: “Who’s your banker? What’s your bank doing? Why your barber school? Why are you coming to us for loans? And they said, ‘There’s nowhere else for us to get loans, my bank won’t make me this loan.’”

Washington started having the barber college set aside $1,000 in profits every month to make low-interest, small dollar loans to the community. That eventually grew into People Trust Community Loan Fund, a not-for-profit, federally-certified community development financial institution, or CDFI. But eventually that proved not to be enough.

“One of the common things that we hear from our loan fund customers is they can’t get a checking account,” Washington says. “They can’t open an account anywhere else. Now when we start you off as a customer with the loan fund…we don’t force you, but we encourage you to open up an account at the credit union.”

It’s never been very easy to start a credit union, but it used to be easier and much more frequent than it has been in recent years. Prior to 1970, it was common to see 500 or 600 new credit unions chartered every year across the entire country. People Trust was one of four new credit unions chartered in 2022; just 25 new credit unions have been chartered over the past 10 years.

There are almost always more interested groups looking to establish new credit unions, says Monica Copeland, MDI network director at Inclusiv, a trade group for credit unions focused on low-to-moderate income communities, “but it’s hard to track until they actually get through the process. It takes organizing groups years.”

Next City previously covered one such effort in Minneapolis back in 2019. It emerged as part of a direct community response to the 2016 police killing of Philando Castile. But even with the additional urgency and momentum from the later Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd, that credit union effort stalled after a leadership transition and frustration with federal credit union regulators. The organizers have yet to receive final approval to open their doors as Arise Community Credit Union.

Or take Everest Federal Credit Union, which is based in Queens, New York and serving Nepali immigrants across the country. Its organizers started their work in 2015 and only recently opened for business. Part of their challenge was the startup capital they had to raise, from donations they ultimately gathered over the past seven years from hundreds of donors across the country.

Each of these efforts has had to go through the National Credit Union Administration – the federal agency that charters, regulates and insures deposits held at U.S. credit unions. The agency didn’t exist until 1970, when Congress created it to oversee the growing credit union industry. It’s technically an “independent” federal agency, meaning like the FDIC or Federal Trade Commission or National Labor Relations Board, the agency’s powers are vested in board members appointed by the President and confirmed by the U.S. Senate. The NCUA’s three-member board must vote to approve key policies like the 18% interest rate cap on all credit union lending or the amount in premiums credit unions pay for federal deposit insurance. Appointed for staggered six-year terms, all three current board members are Trump Administration appointees, although no more than two NCUA board members may be of the same political party.

There are multiple reasons for the dramatic falloff in new credit unions since 1970. Now a credit union consultant, Brian Gately worked as a credit union examiner at the NCUA in the ‘70s and ‘80s. According to Gately, the agency gradually lost touch with its purpose over the course of his tenure. He started out winning awards for helping new credit unions get chartered to serve vulnerable communities in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, but eventually left after refusing orders from higher-ups to shut down a new credit union serving a largely Puerto Rican migrant community on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

“NCUA is getting better now, that’s the good news,” Gately says via email. (The NCUA declined to be interviewed in time for this article.)

Federal credit union regulators do have a history of intentionally encouraging development of new credit unions, particularly in low-to-moderate income communities. The Bureau of Federal Credit Unions, which regulated credit unions from 1934-1970, launched Project Moneywise in 1966 as part of the Johnson Administration’s War on Poverty. Project Moneywise lasted until 1972.

Thanks in part to such efforts, the NCUA still counts 507 minority-designated credit unions today, of which 244 have a majority-Black membership. Compare that to just 145 minority banks, of which 20 are designated as Black minority-depository institutions by the FDIC. While banks and credit unions are similar in many ways, both offering checking accounts and access to basic forms of credit like home loans, auto loans or small business loans, banks are primarily investor-owned for-profit enterprises while credit unions are member-owned not-for-profit cooperatives.

It wasn’t until 2017 that the NCUA created the Office of Credit Union Resources and Expansion, or CURE Office, combining some earlier functions with new resources and a new commitment to streamlining the credit union chartering process. In some ways it mimics how the Federal Aviation Administration provides resources to recruit and train new pilots or how the U.S. Department of Agriculture has extension programs and university partnerships to promote and support the agriculture sector.

Washington has a lot of praise for the CURE Office. He says the staff were tremendously helpful and responsive as he and his team went through the charter application process, which took about a year from when he first sent the agency a letter expressing an interest in chartering a credit union to receiving the final charter approval last September.

People Trust Community Federal Credit Union (Courtesy photo)

Even with more help from the NCUA, parts of the process remain tedious and time consuming. Selecting board members took longer than Washington expected. He needed to find board members who had strong ties to the community – people whom he and the community could trust with setting policies like interest rates or fee structures, but who would also pass NCUA muster on background checks and credit checks. And, unlike bank board directors who typically earn a stipend, credit union board memberships are unpaid, volunteer positions.

“Some of the people that we had in mind to be a board member, because of their credit, after the NCUA did their check, they didn’t qualify,” Washington says. “So we had to go back to the drawing board and get somebody else that we were comfortable with, that we were familiar with, and understands and is passionate about serving on a board that they’re not gonna get paid on.”

By contrast, the marketing plan on the charter application was relatively easy to draft for somebody with decades of experience as a small business owner in the Little Rock community, first as a barber and later as a barber college operator.

“The marketing plan was to really do some guerrilla marketing,” Washington says. “And the way we say we do that is through billboards, local radio stations that our target market listens to, being on the Broadway Joe Show in the morning drive time when they’re on the way to work. The radio has been very effective.”

Word of mouth has also already been surprisingly strong, even more than Washington expected after a few years of operating as a loan fund.

“A lot of the senior citizens came and said, ‘Hey, we’ve been waiting so long or something like this,’” Washington says. “‘We’ve been waiting so long on a minority depository institution that’s homegrown in Arkansas.’”

Operating People Trust Community Loan Fund for several years prior to the application was essential to the chartering process.

As part of the chartering process, credit union organizers need to survey a large enough sample size of their intended community about credit needs that other institutions aren’t meeting — what kinds of accounts, what kinds of loans do members of the target community need and want that they can’t get anywhere else. It was easy enough to send out the survey link to the thousands of people on the loan fund’s existing email contact list until there were enough replies.

The loan fund and its prior track record strengthened People Trust’s credit union charter application. The plan is for the credit union to take over the small dollar consumer loans, including payday loan alternatives and used car loans, that the loan fund has been doing all these years. The loan fund staff have experience making those loans successfully under the nonprofit, and they can point to that track record as evidence they can do that safely and soundly under the credit union side of the house. Meanwhile the loan fund can move up into making larger loans for small business growth and economic development projects perceived as too risky for the credit union.

People Trust’s loan fund/credit union structure today bears a lot of similarities to Community First Fund and its credit union, which Next City covered last year when it opened its doors, as well as Hope Credit Union and its affiliated CDFI loan fund.

It was the loan fund that brought in the financial resources to start up the credit union. In 2019, the loan fund used grant funds to set up an online lending operation to compete with online predatory lenders. That system came online just as the pandemic hit, and eventually allowed People Trust Community Loan Fund to make Paycheck Protection Program loans to anyone around the country who couldn’t get them elsewhere. As a CDFI loan fund, People Trust made around $50 million in PPP loans to more than 2,600 small businesses nationwide, according to Washington.

People Trust earned just over $4 million in fees from making PPP loans, around $3 million of which Washington says it has already put out back on the street in loans. With the remaining $1 million or so, People Trust bought two buildings, one for a second loan fund office and one former bank building to use for its new credit union — and it set aside $450,000 as start-up capital for the credit union.

It’s far from easy chartering a credit union, and Washington is the first to say it’s not for everybody. Part of the reason for People Trust to go through with it was financial sustainability. As interest rates rise, borrowing costs for loan funds, who borrow mostly from big banks, are rising with them. Washington is convinced the credit union can raise and keep its deposits for relatively lower costs, because its customers understand the mission or they value keeping their deposits at an institution headquartered nearby, or they don’t trust other institutions — or because they can’t open an account somewhere else.

“There can be some fear and some apprehension,” Washington says. Many CDFI leaders he speaks with say they don’t want to deal with the regulations of becoming a credit union. But for him, doing so was necessary to develop long-term sustainability.

“We’re not gonna really be able to really impact the community and help out the community like we need to unless we’re able to offer checking accounts and a place where they can store their money that’s in their neighborhood, that understands the cultural difference and the credit needs on a granular level.”

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

This post was originally published on Next City.