Billions of dollars in public money are beginning to flow to seven “hydrogen hubs” around the country — regional nerve centers for a potentially clean fuel that could someday rival solar and wind and cut carbon from the atmosphere. Last week, California’s hub, a public-private partnership called ARCHES, became the first to negotiate an agreement with the Department of Energy to build out hydrogen power plants, pipelines, and other projects.

But researchers and community advocates warn that unless the federal government’s so-called hydrogen earthshot has adequate safeguards, it could worsen air pollution in vulnerable communities and aggravate a warming climate. They’re also concerned that specifics of the emerging efforts remain stubbornly secret from people who live near shovel-ready projects.

That’s true even in California, a state that has declared a commitment not only to ambitious climate goals but also to environmental justice.

“The people got left behind in this conversation,” said Fatima Abdul-Khabir, the Energy Equity Program manager at Oakland-based Greenlining Institute, an advocacy group. “It’s a massive step backwards.”

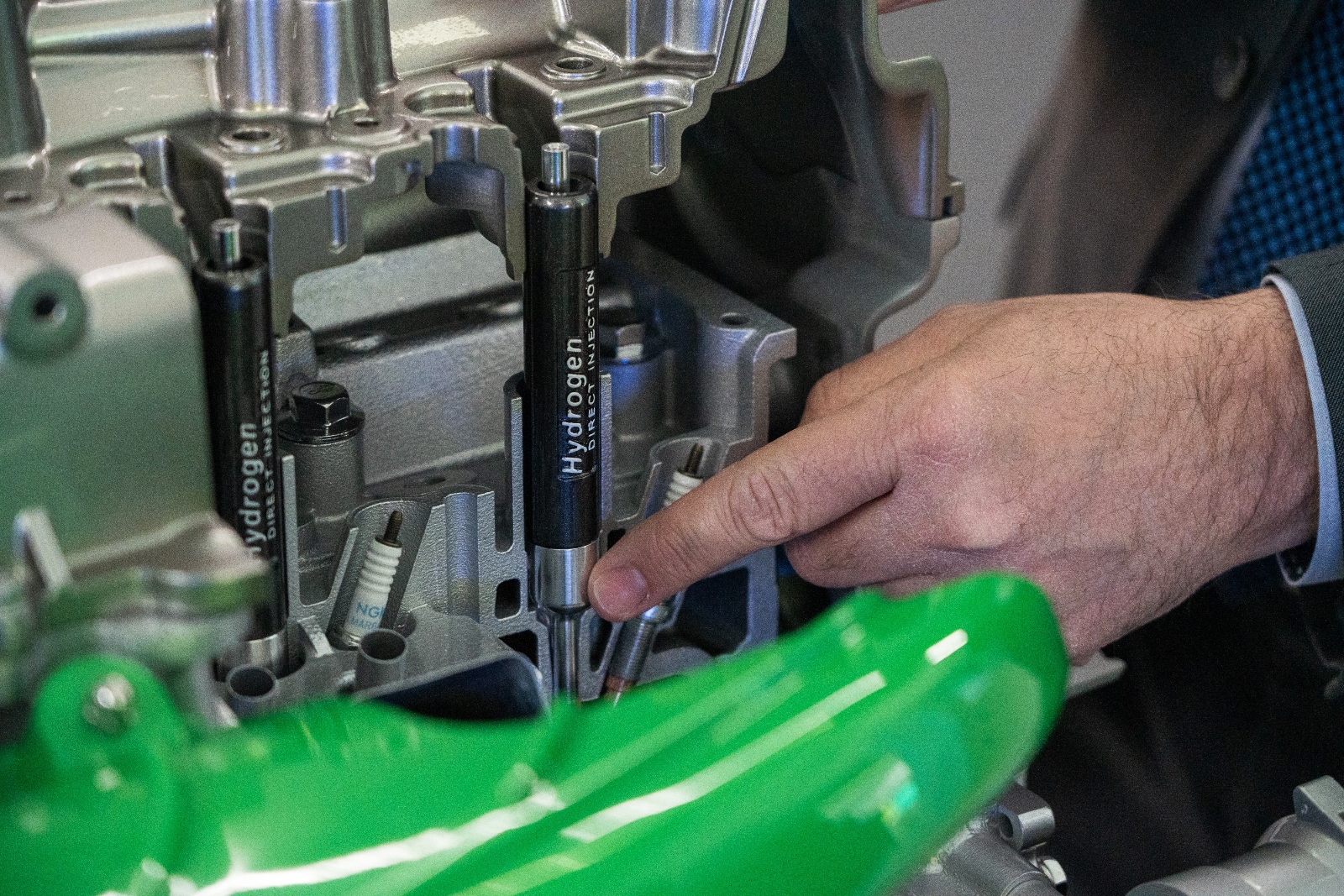

Hydrogen, a colorless, odorless gas, is the world’s most abundant chemical element. When it’s used in fuel cells or burned for energy, it generates no atmosphere-warming carbon emissions. That means it could power trucks and airplanes without spewing soot from a tailpipe or exhaust from an engine. Hydrogen could help steel plants and other heavy industries lower their carbon footprints.

But stripping hydrogen molecules from water or methane to use as fuel can be expensive and complicated, and if that process relies on fossil fuels, it could actually prolong climate pollution. That’s not the only health risk: When even cleanly-produced hydrogen is blended with methane and burned, it can still dirty the air with toxic byproducts that contribute to lung-irritating smog.

The nation’s hydrogen earthshot is a risky and ambitious bet. Congress created an $8 billion pot of money for the hub system. It also tucked nearly $18 billion in grants and incentives into the Inflation Reduction Act and the infrastructure bill. An uncapped federal tax credit for companies that produce hydrogen energy could cost the public at least another $100 billion.

“There’s so much hype right now for hydrogen because everybody wants a piece of the pie,” said Dan Esposito, an electricity policy analyst at the nonprofit firm Energy Innovation.

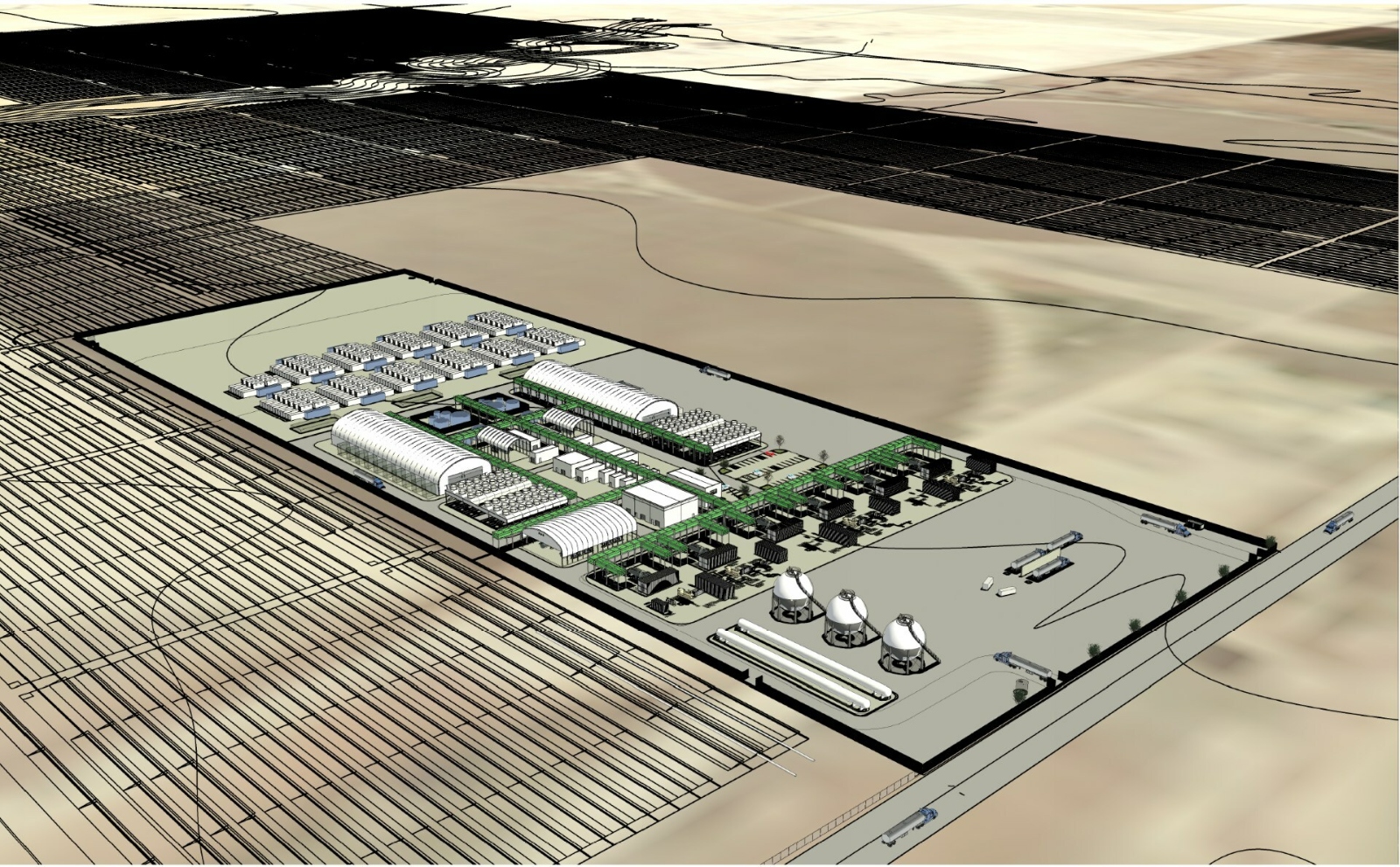

To bring clean hydrogen to market as quickly as possible, the U.S. Department of Energy selected regional hubs based in part on their ability to quickly produce and find uses for clean hydrogen. The chosen hubs also must promise jobs and other community benefits that advance federal environmental justice goals.

But California’s hub, a public-private partnership called ARCHES, is rejecting rules the federal government has proposed to help guard against the risk of rising pollution from incautious hydrogen projects. Along with the six other hubs, ARCHES signed a letter that warns of “far reaching negative consequences” if the rules are made permanent.

The position held by ARCHES is directly contrary to that of experts who say such rules are the only guarantee that this huge investment will lead to a sustainable hydrogen economy.

“What our research has shown is that if we do this wrong from the start, either the hydrogen industry will fall apart or it’s going to lose a bunch of public support or it will really significantly delay our ability to clean up the power grid,” Esposito said.

Multiple analyses based on public data and modeling, including Esposito’s own, have concluded that hydrogen produced under the wrong circumstances could worsen air pollution instead of improving it.

So far, the message from ARCHES is: Trust us. Trust California to do what is right with the $1.2 billion it has been awarded for its hub. Trust the hub’s projects to cut carbon and lung-searing emissions from the air.

“There’s reason to trust California,” said Dan Kammen, an energy professor at the University of California, Berkeley. “But only if California continues to follow the rules that California created.”

California’s hub began as an agreement among the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development, or GO-BIZ, the University of California, the state building and trades unions and a nonprofit called Renewables 100, founded by ARCHES CEO Angelina Galiteva. It has around 400 network partners, including Amazon, Cemex, Chevron and investor-owned utilities, including SoCal Gas and Edison International.

Building on the state’s development of the world’s first standard to cut the carbon intensity of fuel, ARCHES promises to develop zero-carbon hydrogen using solar, wind, biomass and other renewable sources.

“We came together to go after the federal funding, but that federal funding is just a start,” said Tyson Eckerle, a senior advisor for GO BIZ, at an environmental think tank’s conference in the spring. “It’s the pebble that launches the avalanche.”

But California argues that its progress will be slowed if hydrogen developers have to meet rules the U.S. Department of the Treasury has proposed for projects seeking the lucrative 45V tax credit.

Those rules are based on what energy experts refer to as the “three pillars” of clean hydrogen production. To make hydrogen clean and sustainable, it should be produced from a new source using carbon-neutral electricity. That electricity should be geographically close to where it’s needed, so delivering it isn’t costly. It should also be available when it’s needed, not traded or obtained through accounting from another time and place.

California’s hydrogen leaders counter that the state already has a successful strategy — and numerous requirements — for getting clean energy on the grid. Complying with the federal rules would undermine that progress, ARCHES has said in a public response, making it “impossible” to integrate hydrogen “in a timely and cost-effect manner without disrupting our carefully calibrated energy system.”

“We’re at almost 60 percent, 24/7 renewables across the board, which is a huge, huge step forward. We’re ahead of our goals in terms of meeting those obligations,” Galiteva told Public Health Watch.

If these federal conditions “had been required for the nascent solar or battery or any other industry, those industries would never have taken off,” she said.

Julie McNamara, a senior energy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists, called California’s position contradictory. Even if the state’s renewables-rich grid deserves freedom from constraining rules, why would California support a free-for-all that gives states that continue to depend on fossil fuels a pass?

“ARCHES is trying to have it both ways,” she said.

Fossil fuel-focused energy companies, including BP and Shell, have also argued for more leeway in qualifying for the federal money.

Clean hydrogen could be the angel of decarbonizing the energy sector, but Earthjustice senior research and policy analyst Sasan Saadat said that poorly defined hydrogen could be the devil, because it might prolong the use of fossil fuels.

“You’ve taken this thing that is really dangerous and muddled it up with the world of climate solutions and clean energy and that’s why it’s so risky,” Saadat said. “The fossil fuel industry knows this and they can blur the lines.”

ARCHES has prioritized 37 projects to spend its federal money, according to CEO Galiteva. This “tier one” investment reflects the hub’s vision for bringing clean hydrogen to California.

“We have another 33-plus projects … that can actually slide into a tier one project if a tier one project hits a bump on the road for any reason,” she said at a recent hydrogen trade conference in Sacramento. “So the economy and the scale is going to be pretty big once we start moving.”

There’s an incentive to move quickly: To qualify for the federal tax credit, shovels have to be in the ground by 2032.

But the criteria for what qualifies as tier one status aren’t public. Nor are the locations of most of ARCHES’ projects, or their potential health and environmental impacts.

To fully participate in the hub, partners had to sign a nondisclosure agreement. Environmental advocates call the NDA an “iron wall” that makes ARCHES a black box.

“This huge hydrogen thing is happening, and all anybody knows is that there’s a ton of money coming for it,” said Shana Lazerow, a lawyer with the nonprofit Communities for a Better Environment.

Even where hydrogen is produced without fossil fuels, enormous questions remain about where to prioritize its production and use, so it doesn’t pollute or cost more.

“No one has found the killer app for green hydrogen yet,” UC Berkeley’s Dan Kammen said.

Projects that might scoop up the federal money are beginning to emerge from the shadows. In eastern Contra Costa County, where land along the Suisun Bay once served as a stopover for boats supplying gold miners, a company called H Cycle is proposing to heat municipal organic waste to transform it into hydrogen. Diverting waste from a landfill is a particularly attractive idea, since overstuffed landfills release methane into the atmosphere.

But the draft environmental impact report for the project in the small city of Pittsburg is light on details. It’s not clear exactly what will be heated or what technology will be used to unlock the hydrogen. Under California’s regulations, organic waste can include some percentage of plastic and metal, which would emit toxins when burned. The report also references slag, a waste product that comes from burning material, not just heating it.

All of that is troubling to a neighborhood whose residents are in the 93rd percentile statewide for asthma risk. Charles Davidson, a Contra Costa resident and member of the Sunflower Alliance, points out that 25,000 people live near H Cycle. “It’s burning plastics and construction materials and other things with no limit, no specifications on what’s being incinerated next to people’s homes,” he said.

A news release says H Cycle “is positioned” for a piece of ARCHES’ billion-dollar pie. But whether it’s a tier-one project for the hub isn’t clear. H Cycle, as a partner in ARCHES, has signed the hub’s non-disclosure agreement, and the company did not respond to requests for comment.

A letter local air regulators sent to Pittsburg’s planners warns of health risks from the project.

“This thermal conversion process represents a novel renewable hydrogen production strategy,” wrote the Bay Area Air Quality Management District in March. “However, it will introduce additional air pollution into a community that is already overburdened.” The district recommended more consideration of residents – and more transparency.

H Cycle’s engagement with vulnerable communities is limited at best, said Amelia Keyes, a lawyer with Communities for a Better Environment.

“It’s no coincidence that a polluting facility like this is being built here,” she said.

At launch, ARCHES highlighted 10 unnamed hydrogen production projects, “with most in the Central Valley.”

Projects are popping up in marginalized or already-polluted communities around the state. Some involve producing the fuel; others will transport or use it. Amelia Keyes said advocates usually hear about these projects by word of mouth.

“I think it really illustrates the kind of Whac-a-mole that environmental justice groups have to play with these kinds of facilities,” Keyes said.

At the port of Stockton, there’s talk of a facility that would produce hydrogen by steaming it out of methane but could claim to be carbon neutral by using credits for reductions of pollution elsewhere. In a farmworker community in western Fresno County, a pilot project will blend hydrogen into gas lines that go directly into homes for 10,000 people. Southern California Gas is floating the idea of AngelesLink. It’s billed as the nation’s largest clean hydrogen pipeline and could pipe the stuff into the Los Angeles basin. But little information is available yet about where clean fuel will come from in the first place.

Major environmental groups, including Communities for a Better Environment, complain they don’t know much about these projects because they didn’t sign the ARCHES NDA, fearing that the secrecy required would compromise their advocacy in public processes. They worry that health risks and the influence of fossil fuel companies are being waved away.

In a letter to federal energy officials, the California Environmental Justice Association called the NDA a “delay tactic that allowed ARCHES to move forward without needing to account for and include impacted communities in decision-making.”

“Why should we as the public be living in this poverty of information about a massive taxpayer funded climate program?” said Earthjustice energy analyst Sasan Saadat. “It’s really galling.”

People in environmental justice communities are exactly who the California hub claims will benefit from the hydrogen boom. ARCHES says its overall proposal could help the state save nearly $3 billion by increasing “the economic value of health-related benefits” and creating 220,000 new jobs.

In a brief on its website, ARCHES attributes the potential health savings to cleaner air, based on a research paper commissioned by the California Public Utilities Commission. That paper projects reductions in air pollution through the electrification of cars and trucks, ending the use of natural gas in buildings, and removing all emissions from natural gas power generation. It then models the anticipated public health benefits from each. But hydrogen is only glancingly mentioned.

As for the jobs estimate, the independent think tank Rhodium Group offers a stark counter-estimate. It suggests that California’s hub will create just 6,000 to 8,000 jobs during the construction phase and only several hundred long term.

Neighborhoods that might be affected by hydrogen development tend to be wary of promises of jobs or cleaner air. That’s particularly true in the Los Angeles basin, where people have long breathed fossil-fuel driven pollution from refineries and natural gas plants. Now the L.A. Department of Water and Power plans to retrofit one of those plants, the Scattergood Generating Station, so it can run on methane mixed with hydrogen. The plant would produce power to serve the region when demand peaks, as it does on hot days. The estimated cost to retrofit two of the plant’s three turbines is at least $800 million.

But hydrogen burned at high temperatures where oxygen is present, as in a gas plant, can create nitrogen oxides; those, in turn, contribute to ground-level ozone, or smog. Emerging science suggests that blending hydrogen into fossil gas could even increase those emissions, unless pollution controls are added.

“We should not be shooting for extending the life of combustion technology,” Earthjustice analyst Saadat said. “We know that we need to stop burning fuel at the tailpipe and the smokestack.”

ARCHES and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power plan to transition Scattergood to 100 percent hydrogen — “as soon as it is technically and practically feasible to do so.” In the meantime, state officials have acknowledged that the continuing transformation of California’s energy economy comes with tradeoffs.

“Not everything is going to be zero all of the time in terms of emissions,” Rajinder Sahota, deputy executive officer for climate change at the California Air Resources Board, said at the hydrogen summit in Sacramento. “But making sure that, cumulatively, the exposure to harmful pollution is reduced is going to be important.”

The L.A. Department of Water and Power, or LADWP, is also “actively exploring” what happens next at its Valley Generating Station in Sun Valley. Valley notoriously leaked methane, which contributes to smog, for at least three years before officials notified anyone living nearby. The leak prompted a campaign by residents of the largely Latino neighborhood to shut Valley down, and water and power officials say demolition will soon begin. But the 12-acre property remains connected to gas infrastructure, and LADWP emphasizes that having dependable energy generated near where it’s needed in the L.A. basin is essential to a cleaner energy future.

An LADWP spokeswoman said the utility “is actively evaluating hydrogen as well as other emerging technologies [at Valley] that will maximize environmental and equity benefits. We have consistently engaged the community and will continue to do so.”

But residents aren’t reassured.

“So far it’s been hard to understand, Why this? Why this technology?” said Miguel Miguel, a policy advisor for the community advocacy group Pacoima Beautiful.

Miguel says the opaqueness about Valley’s future helped push California environmental justice advocates to circulate principles for an equitable energy transition to hydrogen last year. By their definition, green hydrogen relies on surplus water and renewable energy and doesn’t keep fossil fuels online. It also means communities are consulted respectfully from the start.

“There’s a possibility of green hydrogen as long as it doesn’t exacerbate problems,” Miguel said. “But for us, at Valley … in our opinion it’s the natural gas industry’s last-ditch effort to say, ‘You still need us.’ And that’s the hardest pill to swallow.”

Advocates like Miguel acknowledge that balancing Southern California’s energy sources responsibly, to avoid brownouts or skyrocketing costs, isn’t easy. That’s why they oppose dirty hydrogen — not all hydrogen.

But Martha Dina Arguello, the executive director of Physicians for Social Responsibility-Los Angeles, says talk of green hydrogen has left her frustrated.

“You realize that nobody wants to make green hydrogen, right? There’s no profit in making green hydrogen,” she said. “The political reality is that nobody’s building that right now.”

In the coming months, federal agencies will set policies that clarify the direction ARCHES and the other hydrogen hubs will take.

When Energy Department ARCHES funding, it also finalized the hub’s operating rules. The Treasury Department, too, must finalize guidelines for companies wishing to access hydrogen tax credits. The two agencies don’t always agree; Politico has reported that some in the DOE were advocating internally for weaker rules, as many industry leaders have sought.

Meanwhile, California lawmakers are considering legislation that would streamline the state’s environmental review process for hydrogen projects. And some Democratic members of California’s congressional delegation are lobbying Treasury for weaker rules.

California’s hydrogen boosters seem confident about their strategy.

“Frankly, if you want green hydrogen to succeed, you need California,” ARCHES CEO Galiteva said at the Sacramento summit. She told a story about how Gov. Gavin Newsom sold federal officials on the state’s capacity to advance clean fuel.

Galiteva said the governor emphasized California’s strong climate goals and its robust marketplace for clean energy. And his pitch didn’t stop there.

“You need us more than we need you,” Newsom, by her account, told the DOE. “So you’d better give us a hub.”

Laughter erupted in a ballroom of industry representatives and public officials, as Galiteva smiled. “I guess they listened,” she said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline As US bets big on hydrogen for clean energy, local communities worry about secrecy and public health on Jul 29, 2024.

This post was originally published on Grist.