Drawing by Nathaniel St. Clair

From his locked room, Chester Burnett could hear the trains rattling up the tracks, one every half hour. They reminded him of home, back on Dockery Plantation, when he played on the porches of old shacks with Charley Patton, blowing his harmonica to the rhythm of those big wheels rolling along the rails. Those northbound trains were the sound of freedom then.

Now he was in the madhouse, where grown men, their minds broken by the carnage of war, wailed and screamed all night long. Most of them were white. Some were strapped to their beds. Others ambled with vacant eyes, lost in the big room. Chester just stood in the corner and watched. He didn’t say much. He didn’t know what to say. Sometimes he looked out the barred window across the misty fields toward the river and the big mountains far beyond, white pyramids rising above the green forests.

The doctors came every day, men in white jackets with clipboards. They showed him drawings. They asked about his family and his dreams. They asked if he’d ever killed anyone—he had but he didn’t want to talk about that. They asked him to read a big block of words to them. But Chester couldn’t read. He’d never been allowed to go to school.

The doctors asked all the white men the same questions. Poked and prodded them the same way. Let them sleep and eat together. Left them to comfort each other in the long nights in the Oregon fog.

Chester would play checkers with the orderlies and sing blues songs, keeping the beat by slapping his huge feet on the cold and gleaming white floor. Men would gather around him, even the boys who seemed really far gone would calm down for a few minutes, listening to the Wolf growl out “How Long, How Long Blues” or “High Water Everywhere.” It was odd, but here in the madhouse Chester felt like an equal for the first time.

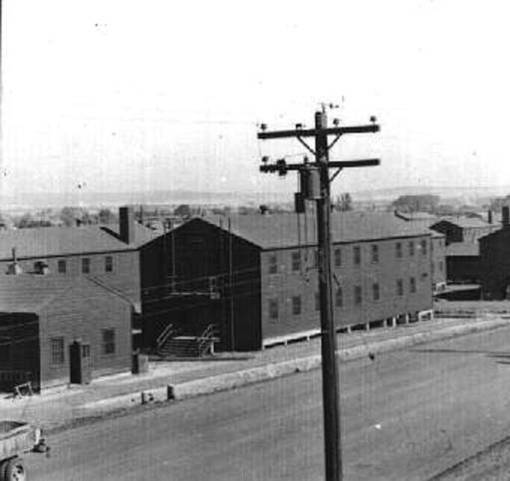

The mental hospital at Camp Adair was located just off of the Pacific Highway on a small rise above the Willamette River in western Oregon, only a few miles south of the infamous Oregon State Hospital, whose brutal methods of mental therapy were exposed by Ken Kesey in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Camp Adair had been built in 1942 as a training ground for the US Infantry and as a base for the 9th Signal Corps. The big hospital was built in 1943. Its rooms were soon overflowing with wounded soldiers from the Pacific theater.

Chester Burnett, by then known throughout the Mississippi Delta as Howlin’ Wolf, had been inducted into the Army in April 1941. Wolf didn’t go willingly. He was tracked down by the agents of the Army and forced into service. Years later, Wolf said that the plantation owners in the Delta had turned him in to the military authorities because he refused to work in the fields. Wolf was sent to Pine Bluff, Arkansas for training. He was thirty years old and the transition to the intensely regulated life of the army was jarring.

Soon Wolf was transferred to Camp Blanding in Jacksonville, Florida, where he was assigned to the kitchen patrol. He spent the day peeling potatoes, and slopping food onto plates as the enlisted men walked down the lunch line. At night, Wolf would play the blues in the assembly room as the men waited for mail call. Later Wolf was sent to Fort Gordon, a sprawling military base in Georgia named after a Confederate general. Wolf would play his guitar on the steps of the mess hall, where the young James Brown, who came to the Fort nearly every day to earn money shining shoes and performing buck dances for the troops, first heard Wolf play. Still, it was a boring and tedious existence.

For some reason, the Army detailed the illiterate Howlin’ Wolf to the Signal Corps, responsible for sending and decoding combat communications. When his superiors discovered that Wolf couldn’t read he was sent for tutoring at a facility in Camp Murray near Tacoma, Washington. It was Wolf’s first experience inside a school and it proved a brutal one. A vicious drill instructor would beat Wolf with a riding crop when he misread or misspelled a word. The humiliating experience was repeated each day, week after week. The harsher the officer treated Wolf, the more stubborn Wolf became. Finally, the stress became too much for the great man and he collapsed one day on base before heading to class. Wolf suffered episodes of uncontrollable shaking. He was frequently dizzy and disoriented. He fainted several times while on duty, once while walking down the hallway.

Barracks at Camp Adair, 1942. Photo: Ben Maxwell (Salem Public Library).

“The Army is hell!” Wolf said in an interview in the 1970s. “I stayed in the Army for three years. I done all my training, you know? I liked the Army all right, but they put so much on a man, you know what I mean? My nerves couldn’t take it, you know? They drilled me so hard it just naturally give me a nervous breakdown.”

Finally, in August 1943, Howlin’ Wolf was transferred to Camp Adair and committed to the Army mental hospital for evaluation. The first notes the shrink scribbled in Wolf’s file expressed awe at the size-16 feet. The other assessments were less impressive, revealing the rank racism that pervaded both the US Army and the psychiatric profession in the 1940s. One doctor speculated that Wolf suffered from schizophrenia induced by syphilis, even though there was no evidence Wolf had ever contracted a venereal disease. Another notation suggested that Wolf was a “hysteric,” a nebulous Freudian term that was usually reserved for women. The diagnosis was commonly applied to blacks by military doctors who viewed them as mentally incapable of handling the regimens of Army life. Another doctor simply wrote Wolf down with casual cruelty as a “mental defective.”

None of the shrinks seemed to take the slightest interest in Chester Burnett’s life, the incredible journey that had taken him from living beneath a rickety house in the Mississippi Delta to the wild juke joints of West Memphis and an Army base in the Pacific Northwest. None of them seemed to be aware that by 1943, Howlin’ Wolf had already proved himself to be one of the authentic geniuses of American music, a gifted and sensitive songwriter and a performer of unparalleled power, who was the propulsive force behind the creation of the electric blues.

Howlin’ Wolf was locked up for two months in the Army psych ward. He was lashed to his bed, his body parts examined and measured: his head, his hands, his feet, his teeth, his penis. The shrinks wanted to know if he liked to have sex with men, if he tortured animals, and if he hated his father. He was beaten, shocked and drugged when he resisted the barbarous treatment by the military doctors. Finally, he was cut loose from the Army, and discharged as being unfit for duty. He was probably lucky he wasn’t lobotomized or sterilized, as was the cruel fate of so many other encounters with the dehumanizing machinations of governmental psychiatry.

“The Army ain’t no place for a black man,” Wolf recalled years later. “Jus’ couldn’t take all that bossin’ around, I guess. The Wolf’s his own boss.”

Sources.

Moanin’ at Midnight: The Life and Times of Howlin’ Wolf by James Segrest and Mark Hoffman

It Came From Memphis by Robert Gordon

Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940–1965 by Morris J. MacGregor

Camp Adair: The Story of a World War II Cantonment: Oregon’s Largest Ghost Town by John H. Baker.

This is excerpted from Sound Grammar: Blues and the Radical Truth (forthcoming from Sitting Sun Press).

The post Conscience of the Blues: How Howlin’ Wolf Got Caged in Oregon appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.