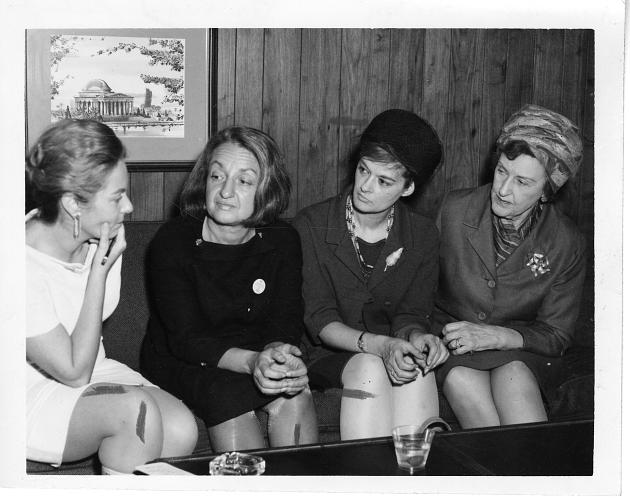

NOW founder and president Betty Friedan (1921–2006) with lobbyist Barbara Ireton (1932–1998) and feminist attorney Marguerite Rawalt (1895–1989)

The National Organization for Women was seen as a radical organization in the 1970s because of its valiant fight to protect reproductive rights for women. But even in those early days, NOW was not radical enough to include black women and LGBTQ as part of their mission. As the times changed and some people of color and LGBTQ members increased in the organization, including in leadership positions, the issues NOW addressed were mainstream, with the focus being on white middle-class women’s rights and some attention to working-class labor issues. In New York State, for example, NOW mostly addressed certification of reproductive rights, shielding sex workers while increasing the offenses for solicitation of sex workers, and protections for pregnant women in the workplace.

In the last few years NOW included intersectionality in its mission, because feminists who were elected to the highest offices of the organization believed that an intersectional lens helped one to look at the intersections of power and privilege, as our identities are marked by race, ethnicity, gender, ability, age, sexuality, wealth, and so on. Reproductive issues, for example, were not just a binary issue of choice versus removal of choice to have an abortion; they incorporated so much more depending on the situation of a woman: her ability to nurture her babies, support for mothers, IVF treatments not just for wealthy people, access to birth control, healthcare for women, trans women getting care, STD testing and treatment, and more. NOW has been slow to catch up on feminist ideas flowering in academia and in women and gender studies conferences. Leading my chapter in Suffolk, Long Island, I was hopeful that we were on the right track to building a nuanced intersectional lens to the issue we addressed.

But after Hamas’ attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, the holes in NOW’s intersectional mission became obvious. Within a week of the attack, NOW put forth a statement denouncing Hamas. It read: “NOW members are sticking fast to our core principles of human rights and freedom from fear, violence, and division. The rise in antisemitism and violent attacks on Jewish communities here and around the world underscore our alarm. The people of Israel live in constant fear of days like today. This is what happens when hate has no boundaries. NOW supports the right of the Jewish people to live without fear or violence, and we condemn antisemitism in all its forms.”

True, we were all horrified at the attack, and especially at the news about vicious sexual assaults on women, which, again, were not verified. (In fact, CDDAW was attacked by US feminists for saying that they can condemn the sexual assaults only after the UN completes the investigation). When Israel’s initial bombardment of Gaza took place, I was shaken when I heard 4000 children were killed in the first few days. When the killing did not stop, I and many others knew we were witnessing genocide, even though there was barely anyone using that term. Then Code Pink came out with their banner and marched to stop the genocide. We were not alone. The world shuddered at the ongoing killing of Palestinian civilians in Gaza. Many members of NOW responded, “No, this is not genocide. Israel is protecting its people. Hamas is using Gazans as human shields. This is Hamas’ war. Blame Hamas, not Israel. Israel has the right to defend itself.”

I attended a meeting of all the NOW chapters, where I stated the urgent need for NOW to come out with a statement calling for a ceasefire in Gaza, especially since the US was supporting Israel by sending arms. The moment I said this, members from different chapters began screaming at me. One said I was offensive by calling Israel’s action genocide. Some said: “How can you use that term on Jews who have gone through the Holocaust?” The word “offensive” in subsequent meetings was used multiple times at the very mention of ceasefire or genocide. Needless to say, upon writing to the President and Vice President of NOW, the Suffolk and Nassau chapters were able to call for a Board meeting to discuss putting together a resolution for a ceasefire. An ad hoc committee of the Board worked on the resolution which was brought to a vote. The resolution failed. One member abstained and a couple of members left the meeting since the vote was called toward the end of a 3-hour meeting where other items on the agenda such as by-laws took precedence. Clearly, the ceasefire resolution was not a priority for NOW, and most of the members of NOW did not really care for the Gaza issue. The question that came up again and again was why were we focusing on an international issue when there are so many national issues that call for our attention? Moreover, NOW is a national, not an international organization. Valid points. But, Suffolk and Nassau chapters asked, why did NOW respond with a statement about Hamas’ attack on Israel, particularly to the sexual assaults? Why was Israel an urgent issue but not Palestine? For that matter, why weren’t we addressing Somalia, Sudan and the Congo? Members who opposed a ceasefire resolution countered with, “Is this a tit for tat?”

I was not surprised that NOW did not really believe in intersectionality, for that would mean applying the rule of equity to different groups. Our chapter demanded equity in how we talked about women’s issues. Why was NOW selective about the populations it supported? Support for Gaza was seen by many members as anti-Semitic. While antisemitism resolutions were introduced in NOW, there was not a single one about countering Islamophobia. Is it any surprise that NOW barely has any Muslim members? Another member asked at one of our national Board meetings, “We are being dragged into someone else’s drama,” without realizing that feminist activism is about being dragged into other people’s dramas! Audre Lorde’s statement was lost on her: “I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.”

Most of the younger feminists in the US support and apply intersectionality to women and gender issues. NOW cannot attract younger feminists, because of the severe lacunae in NOW’s vision that dismisses people who are marginalized. NOW leadership does not see that there is a contradiction in demanding ERA yet opposing Palestinian rights to life, their country, and self-rule. NOW does not see the connection between Black liberation and Palestinian liberation. While speaking strongly against sexual assaults on women, many NOW members don’t see a problem with advocating for victims of sexual assaults but not for women and children blown to bits or undergoing amputations and cesarean sections without anesthesia.

As some newer members observed, NOW is becoming defunct. It is old, stodgy, unwieldy, mismanaged, and disintegrating. While some chapters on the ground are doing some good work, as a national organization it has a brand name but without the substance behind it. It is unable to grow and move beyond the feminism of the 1970s and 80s. Therefore, adding intersectionality is “an empty gesture that reaffirms white supremacy,” say Ashlee Christofferson and Akwugo Emejulu. These authors further assert, “Intersectionality is fundamentally about recognition of the interrelation of structures of inequality (particularly race, class, and gender). Yet recognition of, and engagement with, the interrelationship of inequality structures, requires a prior step of recognizing the ontology of the structures themselves. This refusal to do so is reflected not only among white feminist academics who appropriate the language of intersectionality but fail to name or recognize white supremacy, instead bending and stretching intersectionality in the interests of white women—but also among practitioners.” NOW leaders need to recognize where they are operating out of priorities already established within systemic structures, deconstruct them, and look at issues that people are contending with. This means looking at sexual assault and genocide and ask the difficult questions such as why women are targeted, how as feminists we might advocate for all women, and how we should not allow our language and thinking be coopted by the military lingo used to euphemize horrible truths on the ground. Such an intersectional look at violence against women needs to be paramount in the feminist struggle to bring about change and truly embrace Audre Lorde’s belief in embracing freedom from oppression for all women, irrespective of their nationality, statehood, or other identity markers.

The post The National Organization for Women, Intersectionality and Gaza appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.