Terry Allen, Ancient, 2000–2001, multi-media, 97 x 96 x 78 1/4 in. (246.4 x 243.8 x 198.7 cm), Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA.

What allows you to stay active and engaged in your work?

The simplest way I could answer that would be that I’ve never thought of making art as a career. It’s certainly a job in a sense, but it’s just not a career. It’s a choice you make somewhere down the line about how you’re going to live your life. It doesn’t mean that you don’t have to deal with the same bullshit everybody else has to deal with as far as making a living and all of that, but it’s a shift in your mind where everything you do becomes a part of the same thing. That’s the way I’ve felt about it. Once that decision got made, and I don’t really know when it was, it was probably sometime when I was in school, that’s how I wanted to live my life. That’s pretty much been the throughline from the beginning.

Can you identify other throughlines?

It’s a necessity to confront your curiosity, confront the idea of mystery. When you throw yourself into making something that has never existed before and certainly in your own mind. It takes so long, especially the older you get, to breach your habits because after a certain period of time you have a lot of habits. You try to breach them to get to that mystery spot where things actually happen and you come out on the other side or that piece comes out on the other side and you might have as many questions about it as anybody else does, but it has become what it is. To me as an artist, that’s your job. Whether it’s a song, a sculpture, drawing, whatever it is.

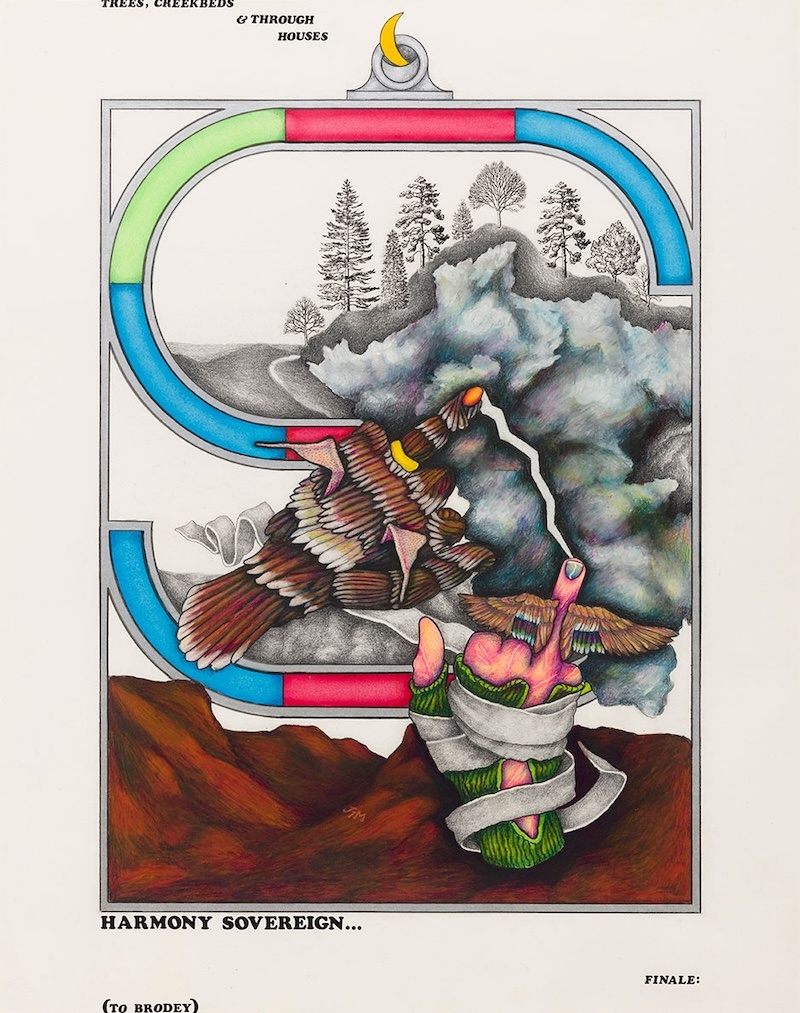

Terry Allen, Harmony Sovereign, 1969, mixed media on paper, 38 1/4 x 31 1/4 in. (97.2 x 79.4 cm), From Cowboy and the Stranger copyright Terry Allen, Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA.

You’ve done a lot of looking back recently, both for the book and reissues of your albums. What’s that been like?

Well the problem with that is that you always want to go forward. The things that you finished are finished and you want to move on, but the nature of the circumstances of your life is that, at least mine, is that, like these reissues with Paradise of Bachelors, had opened up a whole other audience to me and I found myself having to do retrospectives and dealing with the past just like you’re talking about. But at the same time, I’m chomping at the bit to do new work and I’m in the process now of making new work, that’s always the case. I think your curiosity, once something is done, you want to move on. So I don’t feel like I’m dragging stuff with a ball and chain or something behind me, but I’ve just been dealing with the past so much that I’m really glad to be back in my studio and see new things.

Did you have an initial vision of what type of artist you’d like to become as a young person?

No. I never thought that way. I think for one thing, there was nothing visual where I grew up. It was flat and empty and our house was pretty much empty of anything visual. There was an etching of a sailing ship that we had on the wall. My mother had a bunch of bird plates and Gibson Girl prints. That was pretty much it for the visual aspect. I was around a lot of music, but I don’t think I ever thought in terms of, “I’m going to do that,” at that point. It was in high school, when rock and roll hit like a bomb, when I first really wanted to do something, play something, draw something and write something. But it grew that way. It wasn’t any grand, sudden flash of, “This is what I want to do.” Although I did write in notebooks early on that I wanted to be a writer. I wanted to be an artist. I wanted to be a musician. Then I would switch those things around, but I never had any concept of what those even meant. I just had some vague notion, but not as far as any visual stimulation. If you didn’t have an imagination you were dead.

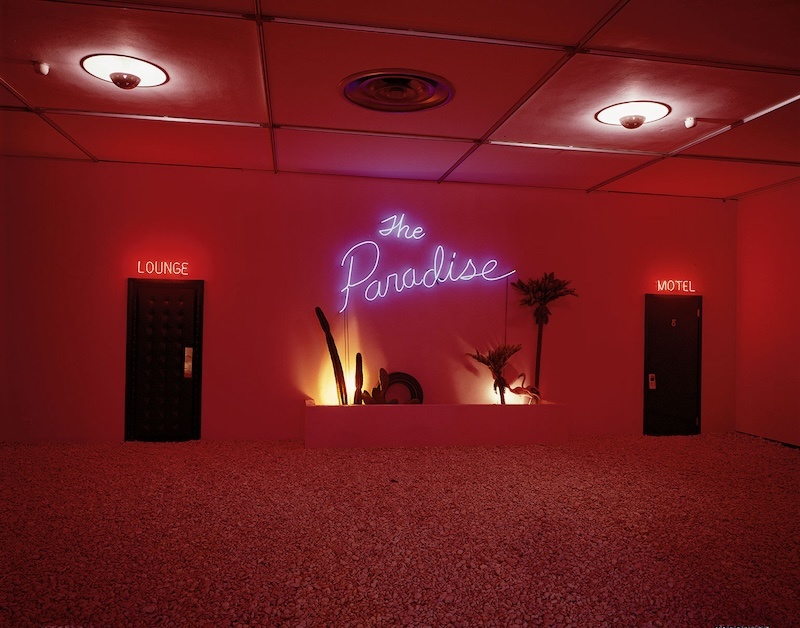

Terry Allen, The Paradise, 1976 as shown in The Great American Rodeo Show, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas, 1976, Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA.

Radio was the sole input that you got from the outside world. Listening to the radio, you’d have to be a moron, a cretin, to listen to those stories and not fabricate some kind of idea of what was going on in your imagination. That was all vivid and alive when I was a little kid. Yeah. A lot of people will trump up whatever they can against their hometowns just to propel themselves out of there. And I certainly did that myself. But there is a great beauty to that flat, endless nothing that you’re looking at, the horizon. Looking at that horizon line, it’s a natural magnet to go past what’s right in front of you into what you can imagine over that line.

You first developed a studio practice in art school. How important was that moment?

It was a huge epiphany, an experience of revelation, whatever you want to call it. Coming from Lubbock to LA, it was like going to Mars. It was the first time you encountered people that were deadly serious about making a picture, about making a song. Whatever they did, it was for real. It wasn’t some Sunday painting club. It was a premeditated act of necessity. That revelation I took to. That atmosphere I took to because it was suddenly finding yourself with a group of like-minded people that were all trying to get the same kind of freedom for themselves, but also in a town that was itself busting wide open. It was such a great time to be in Los Angeles because there were so many things that were happening at once, musically, visually, theater wise. In retrospect it was a major event in my life, going to that school. At the time you were just immersed in it. It wasn’t until it was over that you realized how important it was to you. The people you met, the facility you had, the incredible artists you were privy to and circumstances. It really set a stage for probably everything I ever did afterwards.

Have you come any closer to understanding why ideas come and go?

No. One of the amazing things about being able to make art is every time you begin something, it’s for the first time. You think you have all of this experience of using color or doing this or doing that or whatever, but when you sit down and confront another empty sheet of paper, it’s like you did it the first time. It’s the same with writing a song, that’s the way it is for me anyway. It’s always exciting and spooky at the same time. You can teach tricks, but I don’t think you can teach the heart of the matter.

Your first experience working with a record label wasn’t the greatest. What impact did this have on you?

It was like hitting yourself in the head with a hammer and learning that that hurts and deciding, “Well if I don’t want to hurt, I better not do that again.” It was a situation where I realized my circumstances. If I was ever going to get out into the world in any way, I was going to have to do it myself. And I was tough. I don’t know why, but circumstances just fell right for me, meeting Jack Lemmon in Chicago and Landfall Press and him liking the music and not knowing anymore about making a record than I did, figuring out how to do it. That’s what we did. I’ve always felt that way. If you really want to do something, you just figure out how to do it. You don’t worry about not being able to do it.

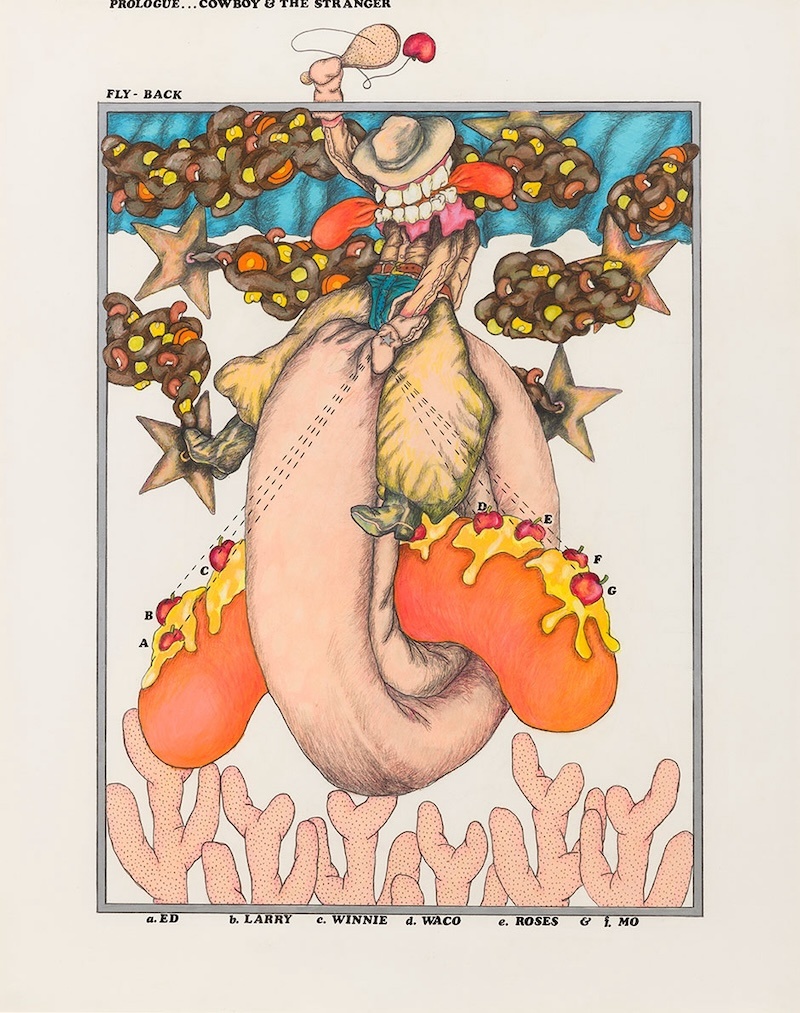

Terry Allen, Prologue … Cowboy and the Stranger, 1969, mixed media on paper, 38 1/4 inches × 31 1/4 inches (framed), From Cowboy and the Stranger copyright Terry Allen, Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA.

That DIY spirit is a common thread between many artists I’ve spoken with.

The last thing in the world I ever thought I would be interested in doing is making bronze sculpture. And I got an opportunity to do a piece in LA called Poets Walk and I happened to meet a guy here who had a foundry who had asked me if I ever wanted to come in and work with him. I had no idea that I would ever take him up on it, but I did and literally went to school at that foundry on my own trying to learn how to do that, working with clay, making the mold and casting, really getting interested in it. That’s another thing about making art, you just never know where it’s going to take you and what you’ll find yourself learning, what you find yourself running into, what you find yourself abandoning. There’s an aspect of making art and being an artist that you crave insecurity to a certain degree. You’re constantly throwing yourself into areas that you don’t know. You don’t know what’s happening. How do you know how it’s going to turn out until you throw yourself into it and find out? That’s just one of the inherent natures of making things.

You’ve had a longstanding journaling practice. Do you always use the same type of notebook, pen or pencil?

I don’t. I grab whatever’s handy. I’ve always been a sucker for collecting empty books and I’ve got all different kinds. When one thing gets filled up, I grab whatever strikes my eye and write in it, but I don’t have a uniform. I did go through a period where I found these really nice books in Italy and used them a lot, but I don’t have any preference. If it’s nice paper and it feels good when you’re putting a pen on it, then that’s good for me.

Terry Allen, Corporate Head, 1990, bronze, with poem by Philip Levine 30 inches × 22 inches, Citicorp Plaza ‘Poets’ Walk,’ Los Angeles, California copyright Terry Allen Photo by, and courtesy of, William Nettles.

How do you have your studio organized?

I’ve got my keyboard and all my recording stuff in one room, then a big space that I have all of the other stuff in. It’s all one space. I periodically move my keyboard into the other space and will play music looking at certain pictures or certain ideas for video. It’s mobile in that sense. That’s another throughline, things being mobile, everything always being in motion. A good portion of my songs, especially early songs, came out of driving.

I love hearing about folks writing while in motion.

My first car had this white Naugahyde in between the seats. I would start thinking of songs and have a ballpoint or pencil, trying to write stuff down while I was driving. I had it written all over the Naugahyde. It comes from boredom, the motion of tires, the rhythm of it. It’s always been conducive to lyrics starting to happen and rhythms, melodies.

Is there anything else you want to talk about?

I just wanted to say that I’m really honored that Brendan did this book. It came out of a long association over a long period of time. All of the liner notes, everything he’s written, was the genesis of the book. I’m very proud of what he did and I probably haven’t told him that enough, but it’s true. He’s been a remarkable ally.

Everyone needs someone in their corner. It changes things.

It does, on a lot of levels. I couldn’t be more appreciative. It’s a very odd experience to have a book written about yourself because you have so many different selves that you’re dialing through every day that you wonder which one they’re going to pick.

Did it start to play tricks on your memory?

I have a pretty relaxed attitude about memory because I’ve never thought of it as anything other than fiction. Brendan delved into a lot of things that I haven’t thought about and found out a lot of things I didn’t know. That was, I can’t say shocking, but it was certainly unnerving at certain times and we talked a lot about that. How many different vantage points are there at looking at a person and looking at a life, whether it’s your own or whether it’s somebody else’s? You can stand on one side and see one thing, but when you get on the other, you see something else. The way he shuffled his way through that was remarkable. It’s a great thing to have for my kids. There’s a lot of history that he found out I didn’t know and now they have privy to.

I’d imagine it helped that you two already had a close working relationship.

That’s one thing that propelled the whole thing into motion. People were starting to ask me if they could do a biography. I talked to Brendan about it and I said, “Well, would you do it?” He said that he had been thinking about doing it. That’s where it started and then he took five years of his life to deal with it. Five years of mine too. It’s been a ride.

Terry Allen recommends:

Flights by Olga Tokarczuk

The Wild Bunch (End of the Line Edition) Jerry Goldsmith, Motion Picture Soundtrack

Perfect Days by Wim Wenders and Pina by Wim Wenders (3D)

American Utopia, a Musical Theater by David Byrne, Film by Spike Lee

Win Win, an album by Sam Baker

This content originally appeared on The Creative Independent and was authored by Jeffrey.

This post was originally published on Radio Free.