COMMENTARY: By David Robie

Vietnam’s famous Củ Chi tunnel network was on our bucket list for years.

For me, it was for more than half a century, ever since I had been editor of the Melbourne Sunday Observer, which campaigned against Australian (and New Zealand) involvement in the unjust Vietnam War — redubbed the “American War” by the Vietnamese.

For Del, it was a dream to see how the resistance of a small and poor country could defeat the might of colonisers.

- READ MORE: Flashback to the 1968 My Lai massacre: ‘Something dark and bloody’

- Ho Chi Minh City’s War Remnants Museum

“I wanted to see for myself how the tunnels and the sacrifices of the Vietnamese had contributed to winning the war,” she recalls.

“Love for country, a longing for peace and a resistance to foreign domination were strong factors in victory.”

We finally got our wish last month — a half day trip to the tunnel network, which stretched some 250 kilometres at the peak of their use. The museum park is just 45 km northeast of Ho Chi Minh city, known as Saigon during the war years (many locals still call it that).

Building of the tunnels started after the Second World War after the Japanese had withdrawn from Indochina and liberation struggles had begun against the French. But they reached their most dramatic use in the war against the Americans, especially during the spate of surprise attacks during the Tet Offensive in 1968.

The Viet Minh kicked off the network, when it was a sort of southern gateway to the Ho Chi Minh trail in the 1940s as the communist forces edged closer to Saigon. Eventually the liberation successes of the Viet Minh led to humiliating defeat of the French colonial forces at Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

Cutting off supply lines

The French had rebuilt an ex-Japanese airbase in a remote valley near the Laotian border in a so-called “hedgehog” operation — in a belief that the Viet Minh forces did not have anti-aircraft artillery. They hoped to cut off the Viet Minh’s guerrilla forces’ supply lines and draw them into a decisive conventional battle where superior French firepower would prevail.

However, they were the ones who were cut off.

The Củ Chi tunnels explored. Video: History channel

The French military command badly miscalculated as General Nguyen Giap’s forces secretly and patiently hauled artillery through the jungle-clad hills over months and established strategic batteries with tunnels for the guns to be hauled back under cover after firing several salvos.

Giap compared Dien Bien Phu to a “rice bowl” with the Viet Minh on the edges and the French at the bottom.

After a 54-day siege between 13 March and 7 May 1954, as the French forces became increasingly surrounded and with casualties mounting (up to 2300 killed), the fortifications were over-run and the surviving soldiers surrendered.

The defeat led to global shock that an anti-colonial guerrilla army had defeated a major European power.

The French government of Prime Minister Joseph Laniel resigned and the 1954 Geneva Accords were signed with France pulling out all its forces in the whole of Indochina, although Vietnam was temporarily divided in half at the 17th Parallel — the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh, and the republican State of Vietnam nominally under Emperor Bao Dai (but in reality led by a series of dictators with US support).

Debacle of Dien Bien Phu

The debacle of Dien Bien Phu is told very well in an exhibition that takes up an entire wing of the Vietnam War Remnants Museum (it was originally named the “Museum of American War Crimes”).

But that isn’t all at the impressive museum, the history of the horrendous US misadventure is told in gruesome detail – with some 58,000 American troops killed and the death of an estimated up to 3 million Vietnamese soldiers and civilians. (Not to mention the 521 Australian and 37 New Zealand soldiers, and the many other allied casualties.)

The section of the museum devoted to the Agent Orange defoliant war waged on the Vietnamese and the country’s environment is particularly chilling – casualties and people suffering from the aftermath of the poisoning are now into the fourth generation.

The global anti-Vietnam War peace protests are also honoured at the museum and one section of the compound has a recreation of the prisons holding Viet Cong independence fighters, including the torture “tiger cells”.

A guillotine is on display. The execution method was used by both France and the US-backed South Vietnam regimes against pro-independence fighters.

A placard says: “During the US war against Vietnam, the guillotine was transported to all of the provinces in South Vietnam to decapitate the Vietnam patriots. [On 12 March 1960], the last man who was executed by guillotine was Hoang Le Kha.”

A member of the ant-French liberation “scout movement”, Hoang was sentenced to death by a military court set up by the US-backed President Ngo Dinh Diem’s regime.

In 1981, France outlawed capital punishment and abandoned the use of the guillotine, but the last execution was as recent as 1977.

Museum visit essential

Visiting Ho Ch Min City’s War Remnants Museum is essential for background and contextual understanding of the role and importance of the Củ Chi tunnels.

Back in my protest days as chief subeditor and then editor of Melbourne’s Sunday Observer, I had published Ronald Haberle’s My Lai massacre photos the same week as Life Magazine in December 1969 (an estimated 500 women, children and elderly men were killed at the hamlet on 16 March 1968 near Quang Nai city and the atrocity was covered up for almost two years).

Ironically, we were prosecuted for “obscenity’ for publishing photographs of a real life US obscenity and war crime in the Australian state of Victoria. (The case was later dropped).

So our trip to the Củ Chi tunnels was laced with expectation. What would we see? What would we feel?

The tunnels played a critical role in the “American” War, eventually leading to the collapse of South Vietnamese resistance in Saigon. And the guides talk about the experience and the sacrifice of Viet Cong fighters in reverential tones.

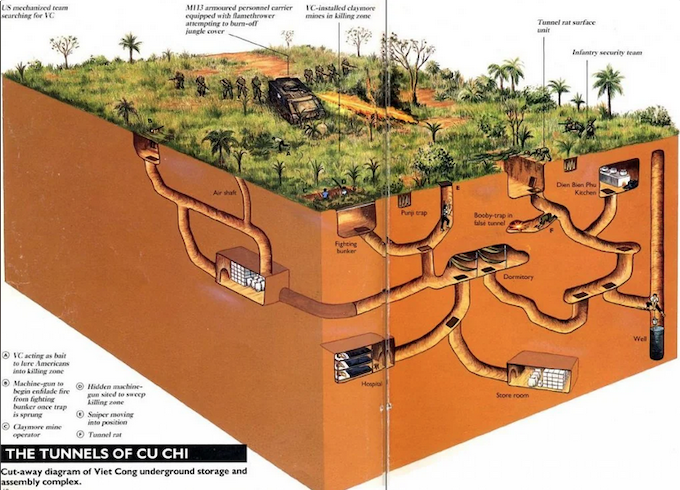

The tunnel network at Ben Dinh is in a vast park-like setting with restored sections, including underground kitchen (with smoke outlets directed through simulated ant hills), medical centre, and armaments workshop.

ingenious bamboo and metal spike booby traps, snakes and scorpions were among the obstacles to US forces pursuing resistance fighters. Special units — called “tunnel rats” using smaller soldiers were eventually trained to combat the Củ Chi system but were not very effective.

We were treated to cooked cassava, a staple for the fighters underground.

A disabled US tank demonstrates how typical hit-and-run attacks by the Viet Cong fighters would cripple their treads and then they would be attacked through their manholes.

‘Walk’ through showdown

When it came to the section where we could walk through the tunnels ourselves, our guide said: “It only takes a couple of minutes.”

It was actually closer to 10 minutes, it seemed, and I actually got stuck momentarily when my knees turned to jelly with the crouch posture that I needed to use for my height. I had to crawl on hands and knees the rest of the way.

A warning sign said don’t go if you’re aged over 70 (I am 79), have heart issues (I do, with arteries), or are claustrophobic (I’m not). I went anyway.

People who have done this are mostly very positive about the experience and praise the tourist tunnels set-up. Many travel agencies run guided trips to the tunnels.

“Exploring the Củ Chi tunnels near Saigon was a fascinating and historically significant experience,” wrote one recent visitor on a social media link.

“The intricate network of tunnels, used during the Vietnam War, provided valuable insights into the resilience and ingenuity of the Vietnamese people. Crawling through the tunnels, visiting hidden bunkers, and learning about guerrilla warfare tactics were eye-opening . . .

“It’s a place where history comes to life, and it’s a must-visit for anyone interested in Vietnam’s wartime history and the remarkable engineering of the Củ Chi tunnels.”

“The visit gives a very real sense of what the war was like from the Vietnamese side — their tunnels and how they lived and efforts to fight the Americans,” wrote another visitor. “Very realistic experience, especially if you venture into the tunnels.”

Overall, it was a powerful experience and a reminder that no matter how immensely strong a country might be politically and militarily, if grassroots people are determined enough for freedom and justice they will triumph in the end.

There is hope yet for Palestine.

- The Melbourne-based Asia Vacations Group has recently expanded its Vietnam offering in New Zealand.

This post was originally published on Asia Pacific Report.