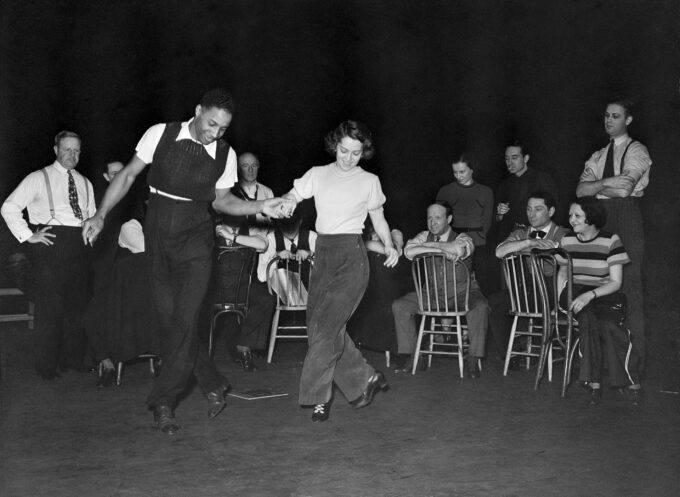

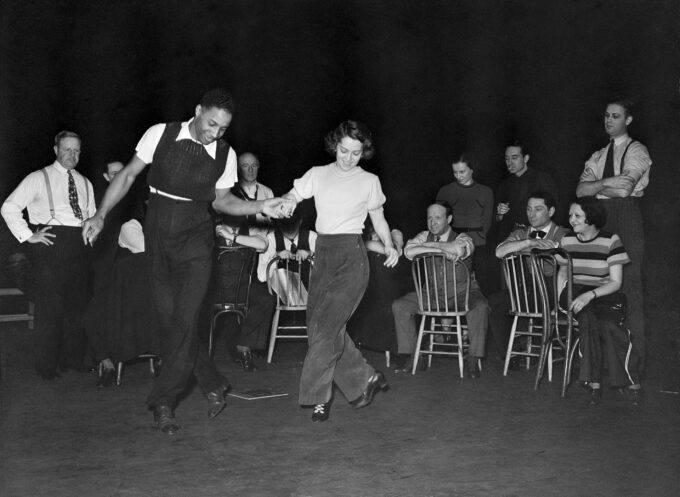

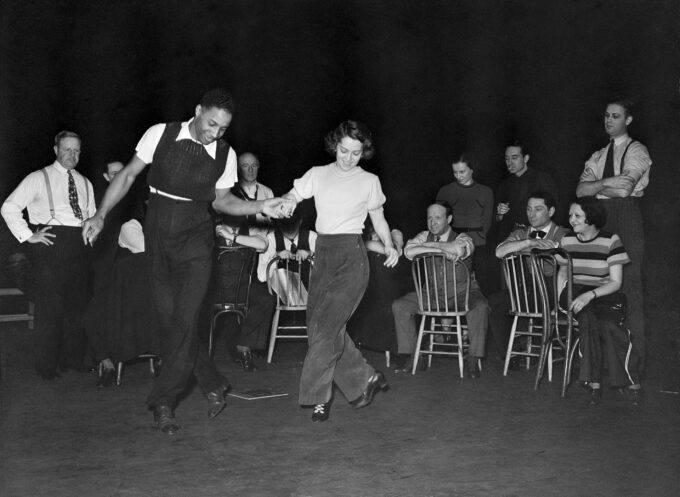

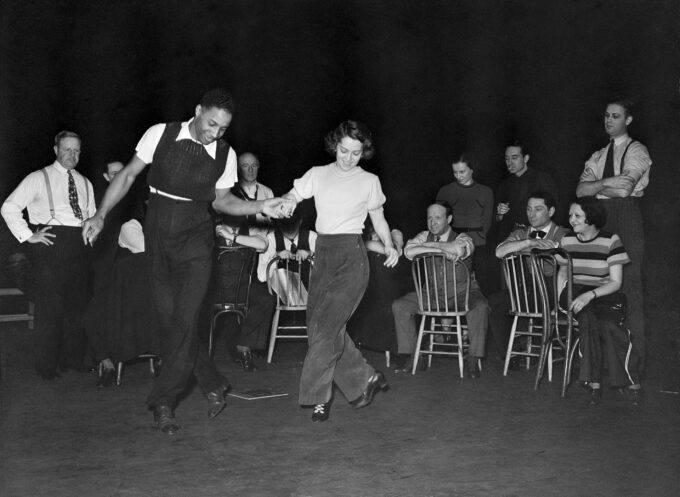

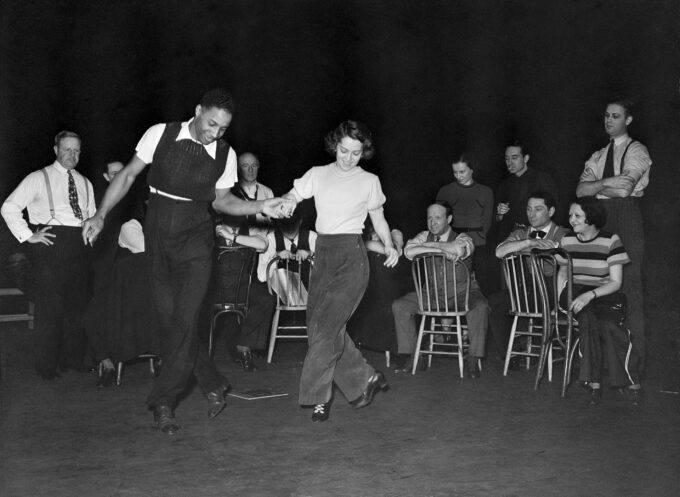

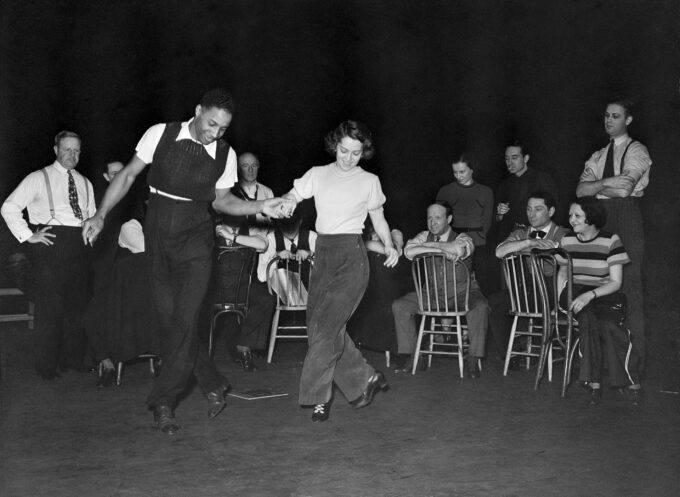

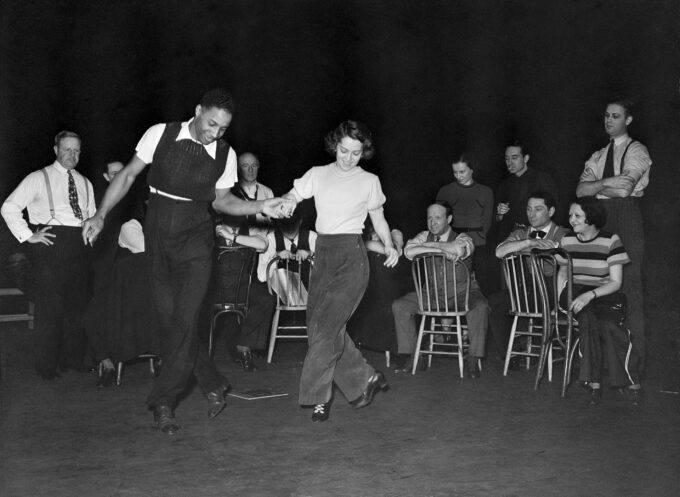

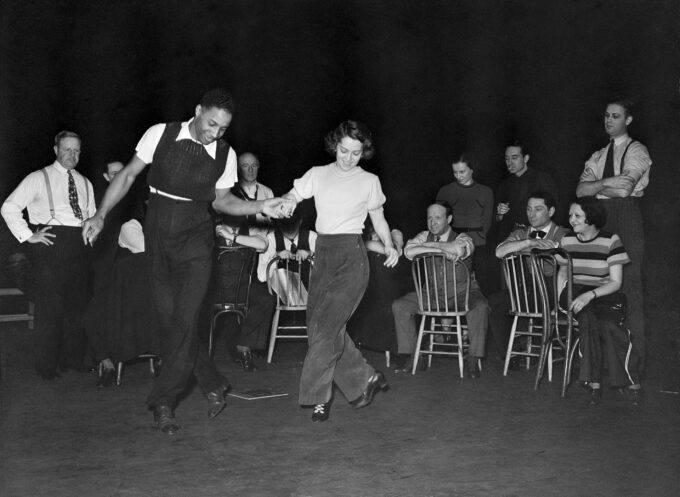

Photograph of choreographer Clarence Yates rehearsing a musical sequence with Olive Stanton for the Federal Theatre Project production of The Cradle Will Rock, as other cast members look on. Photo: Library of Congress.

In award-winning historian James Shapiro’s excellent book, The Playbook: A Story of Theater, Democracy, and the Making of a Culture War, he makes the case for how the twenty-first century’s culture wars follow a playbook established during the culture wars of the twentieth century. To illustrate his argument, Shapiro directs a spotlight on the Federal Theatre Project (FTP), one of five arts-related Federal One Projects formed within the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

Set up to help the nation recover from the Great Depression by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Executive Order 7034 on May 6, 1935, the Federal One projects that supported the arts are generally viewed as a golden period in our nation’s cultural history. Under the WPA, arts were made accessible through presentations of dance, theater, and music performances, visual artworks, literary publications, and classes in all forms of performing, visual, and literary arts. These New Deal arts programs made it possible for many of the most iconic American artists of the 20th century to fulfill their promise, besides starting others on their careers.

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP) was instituted to create a national theater, by employing theater workers on public relief, and having them create live performing arts events throughout the nation. The high unemployment rate among theater workers had occurred because the film industry shifted from silent to sound technology. Theaters suffered, causing many to close or significantly reduce the number of presentations in a season.

At one point, during the Federal Theatre Project’s existence, from 1935 to 1939, it employed 12,700 people. FTP job titles encompassed actors, writers, directors, designers, theater musicians, dancers, technicians, box office staff, ushers, maintenance workers, and the accounting and secretarial force necessary to support around sixty thousand performances.

The majority of these performances were free and seen by thirty million people (close to one out of four Americans). They took place in streets, parks, schools, baseball fields, and theaters, produced by various units within the project, including African American, Italian, Spanish, Yiddish, French, and German units. New York City, Boston, and California were the most active centers: New York City had a payroll of 5,000 people early in its history and thirty-one producing units; Boston had thirty-three producing units; California’s thirty-two units employed 1650 people. 900 plays by Shakespeare, Chekhov, George Bernard Shaw, T.S. Eliot, Eugene O’Neill, and other classical and modern  playwrights of American and international renown were presented, besides puppet theater, group improvisations, dance, vaudeville, and circus events. (A young Burt Lancaster was documented in photographs performing as an aerialist and on parallel bars in the FTP’s Circus Unit.) New works were encouraged, including one 1937 Detroit performance at a Jewish Community Center of They Too Rise by Arthur Miller, then an unknown playwright. A rewrite of his first play, it was described as “an unbearably dull play” in one play reader’s report. Nevertheless, Miller remained with the FTP until it ended, writing radio plays and scripts. The Living Newspaper Unit, in an alliance with journalists in the Newspaper Guild, provided another source for new plays. Since Living Newspaper plays dramatized current events, addressing such issues as public health, slum housing, sweatshops, and the rising threat of fascism, this particular FTP unit was to become a popular scapegoat of Congressional conservatives.

playwrights of American and international renown were presented, besides puppet theater, group improvisations, dance, vaudeville, and circus events. (A young Burt Lancaster was documented in photographs performing as an aerialist and on parallel bars in the FTP’s Circus Unit.) New works were encouraged, including one 1937 Detroit performance at a Jewish Community Center of They Too Rise by Arthur Miller, then an unknown playwright. A rewrite of his first play, it was described as “an unbearably dull play” in one play reader’s report. Nevertheless, Miller remained with the FTP until it ended, writing radio plays and scripts. The Living Newspaper Unit, in an alliance with journalists in the Newspaper Guild, provided another source for new plays. Since Living Newspaper plays dramatized current events, addressing such issues as public health, slum housing, sweatshops, and the rising threat of fascism, this particular FTP unit was to become a popular scapegoat of Congressional conservatives.

A young theater professor, Hallie Flanagan, appointed the National Director of the FTP, wrote from Nebraska in 1936: “Our actors…found that 90 percent of their audience had never seen a play and could not believe that the actors were not moving pictures. After each performance they would wait in the doorway to see ‘whether the people are real.’” Studs Terkel, one of the great artists whose career was nurtured by the WPA, reminisced about the FTP: “It proved that there is a hunger for good, alive, pregnant theater in this country, no matter where it is performed.”

One of the most famous FTP productions, to which Shapiro gives considerable focus, is New York’s Negro Theatre Unit’s 1936 production of Shakespeare’s Macbeth at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem. Reset in a Haitian jungle and known as the “Voodoo Macbeth,” it was produced by John Houseman, employed an all-Black cast of 150 actors, dancers and musicians, was directed by a twenty-year-old wunderkind, Orson Welles, with choreography and drumming by Sierra Leone born Asadata Dafora, a highly regarded dancer and musician of that time. After Macbeth had a sold-out ten-week run in Harlem, it moved to Broadway for a brief run and then toured the country in WPA-sponsored performances. Although Richard Wright, active in the Chicago unit of the Federal Writers’ Project, advocated for Black plays that “create a Negro theatre literature and at the same time create and organize an audience for itself,” he saw some progress in the New York production of Macbeth, commenting that: “‘The long evolution of the Negro actor from the clowning minstrel type to Edna Thomas’ lofty portrayal of Lady Macbeth represents a span of years crowded with abortive efforts.’ As such, Macbeth, in which ‘talent long stifled rose to the surface and compelled public attention. . . presented a compromise,’ providing ‘Negro actors a wide scope for their talent’ while dealing ‘with a theme which was acceptable to a white theatre-going audience.’ (76)” In a 1982 BBC interview, Welles said, “By all odds my great success in my life was that play.”

Another famous FTP performance project Shapiro features is the staging of Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 best-selling novel, It Can’t Happen Here, about the rise of a fascist dictatorship in America. Adapted by Lewis with John C. Moffitt, twenty-one productions were viewed by over half a million people from its opening “in eighteen cities on the evening of October 27, 1936. (102)” “In the Yiddish production in New York, seen by over 25,000 playgoers in all, the future film director Sidney Lumet played young David [Greenhill, a character seduced by the propaganda of the Minuet Men, a private militia similar to the SS and SA in Hitler’s Germany], and several playgoers, perhaps refugees from Nazi persecution, fainted during the concentration camp scene (103).” By the end of its run, nearly 500,000 people had seen a production of It Can’t Happen Here. Hallie Flanagan described the play’s mixed critical reception: “There were stories and editorials for and against from one end of the country to another. Some people thought the play was designed to re-elect Mr. Roosevelt; others thought it was planned in order to defeat him. Some thought it proved Federal Theatre was communistic; others that it was New Deal; others that it was subconsciously fascist. (96) Sinclair Lewis stated “It is propaganda for an American system of Democracy. Very definitely propaganda for that. (96)”

In 1938, Congress appointed Representative Martin Dies, a Republican from East Texas, as Chairman of the Committee to Investigate Un-American Activities, later renamed the Committee on Un-American Activities. Popularly known as the Dies Committee, their task was to investigate if Communist Party members or sympathizers had infiltrated New Deal programs. Although basically created by Dies to provide a forum to heighten his own profile and power, he pioneered the right-wing political playbook now called “culture wars.” Even then, a surprising three-quarters of the American public supported the Dies Committee’s investigation of the WPA and their debate about “the place of theater in American democracy (242).” When the committee found that un-American Communist activities existed within WPA meetings and activities, Representative John Martin of Colorado denounced their report, saying, “This committee is having the effect of identifying in the public mind New Dealism, liberalism, and labor, with radicalism and Communism…If it keeps on, it will dig more graves for Democrats than for Communists.” (248).

Shapiro writes that what “…conservative commentator Jeane J. Kirkpatrick later said about Senator Joseph McCarthy’s war on Communism was even more true of Dies’s battle with Flanagan: McCarthyism was not so much about Communism as it was a struggle for ‘jurisdiction over the symbolic environment….What was at issue was who would serve as the arbiter of culture and whose narrative would prevail. (238)”

In the 1930s, the anti-arts focus centered around cutting funding for the WPA’s Federal Theatre Program. By June 1939, it was the first and only WPA project whose funding was eliminated. All appropriations for other WPA activities were cut by 1943, mainly due to US engagement in World War II, besides the efforts of Dies’ Committee on Un-American Activities. Our nation has never been able to replicate the WPA programs’ expansive vision in support of the arts.

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), established in 1965 during the Johnson administration along with the National Endowment for the Humanities, became the nation’s successor to the WPA’s arts programs. Learning from the WPA’s administrative history, NEA administrators recognized that offering Federal Theatre projects in just twenty-seven states was a weakness to avoid, as the more states their programs touched, the more likely it would be that their Congressional representatives would defend funding these programs. Although, over the years, conservative Congressional attacks slashed the NEA’s budget to a fraction of its original size, starting in 1981 with the Ronald Reagan administration (266), this strategy has helped the NEA continue to exist as a line item in every federal budget.

However, motivated by both extreme right grassroots and political agendas, the arts have continued to be the first culture wars’ scapegoat. The 1990s was an especially virulent time, when the bugaboo was the NEA’s funding to individual visual artists. Citing their themes of sexuality, gender, subjugation, and personal trauma, Congress ruled that some artists’ works were criminally obscene. The Congressional campaign to cut certain individuals’ grants also extended to cutting funding of museums that exhibited their works. Four solo performance artists–Karen Finley, John Fleck, Holly Hughes, and Tim Miller–sued the NEA and its chair, John Frohnmayer, for violating their constitutional right to freedom of expression. Although the four artists won a partial out-of-court settlement, Congress stopped the NEA’s funding of individual artist programs. The four performance artists continued their legal challenges when Congress amended the federal funding statute for the arts with a “decency clause.” In 1998, the Supreme Court ruled that the language of the “decency clause” was “advisory” rather than “obligatory.”

In the 2020s, writers, teachers, and librarians are being targeted through book bans, focusing on removing from the curriculum or library shelves any books considered “sexually explicit,” containing “offensive language,” or material “unsuited to any age group,” such as books with LBGTQ+ characters and people of color, and those presenting the factual history of slavery, Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era, or the WW II Holocaust. The 2021 Virginia gubernatorial candidate, Glenn Youngkin, featured banning Nobel prize winning author Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved from school curriculums as a central talking point of his successful campaign. Although students and teachers have waged protests and publishers and librarians have filed lawsuits to defend their First Amendment rights, by 2023, 4,240 unique titles were prohibited nationwide. Libraries that shelved these titles have received bomb threats, and librarians, parents, teachers, and school board members have been doxed, threatened, and even sued or fired for challenging these bans.

Shapiro closes his book with cautionary examples of how, in recent years, theater has again become a hot-button issue. School districts across the country have canceled high school productions of plays, such as The Crucible by Arthur Miller in Fulton, Missouri, after community complaints about theater encouraging “immoral behavior”; August Wilson’s Fences, in Iowa, for not including white characters; The Laramie Project, in Texas, for its subject of the 1998 murder of a gay student in Wyoming. Florida’s 2023 Parental Rights in Education Act demands the removal of any material concerned with gender identity and sexual orientation from classrooms. Even readings of some Shakespeare plays, long a standard subject of College Board exams, have been censored: A Midsummer Night’s Dream is completely banned in Florida’s middle school classrooms and only excerpted scenes from Romeo and Juliet are allowed to be taught. The plays are not even permitted to be shelved in Florida’s school libraries (268).PEN America reported that during the 2023 to 2024 school year, more than 10,000 books were banned in U.S. public schools. This tally is nearly triple the amount from the previous year, although the actual number of books banned is higher than those reported. []

Conservatives’ treatment of the arts is a harbinger of their attitudes toward other aspects of American life. The Dies Committee’s 124-page official report to Congress caused the termination of the Federal Theatre Project funding in 1939, although the FTP was barely mentioned in their report (248). Flash forward to the conservative think-tank, the Heritage Foundation, funded by Gulf Oil, which has tried to eliminate the NEA for many years, issuing “Ten Good Reasons to Eliminate Funding for the National Endowment for the Arts” in 1997. This review mentions right-wing tactics to ban books and plays during the Biden administration years. Were the arts culture wars waged in some part to prepare the nation for instigation of the policies proposed during the 2024 Trump/Vance campaign and those goals discussed in the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, an agenda prepared in partnership with 140 former Trump administration staffers? It includes: raids and mass deportations in immigrant communities; targeting of protestors and journalists who question Federal law enforcement practices; criminalization of standard voting processes; censorship of school curriculums with warnings that infringements will result in cuts in federal funding if discussions of race, gender, and our nation’s historical practices of systemic oppression are presented; and mass firings and even incarceration of bureaucratic, political and judicial adversaries. By reminding people that these tactics have a long history, The Playbook is right on time, confirming the maxim, frequently invoked by both Republicans and Democrats, that liberty must constantly be fought for and defended by each generation. Shapiro’s 69-page bibliographical essay documenting his research offers readers sources to go deeper into the culture war stories he explores in his book–of idealistic dreams to make the arts accessible to all Americans juxtaposed with the often-successful strategies to stop these efforts.

The right wing comes for the arts first, the most vulnerable of American institutions. Then they go on the prowl for other targets.

The post Culture Wars Redo appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.