At this hour, America is experiencing a crucial step in a peaceful transition of power.

In a joint session of Congress, the president of the Senate is presiding over the certification of the incoming president’s victory. It so happens that this president of the Senate is one Kamala Harris, the vice president, and the victory she is certifying is that of Donald Trump, who defeated her.

Does that mean that all is well with democracy in America? Far from it.

The reason today will be smooth is because the political party that has allowed anti-democratic tendencies to swallow it whole happens to have won more or less fair and square. When Republicans win elections, they somehow become committed to them.

As President Biden wrote in The Washington Post this weekend, the only reason we’re getting an orderly transition is because the outgoing Democrats are committed to it, despite the ongoing attempts by Republicans to rewrite history in their attempt to erase the reality of what happened in 2021.

The attacks on accountability are only going to continue. The speaker of the House, Mike Johnson, has reaffirmed his intention to continue the erasure of January 6, 2021, by opening investigative hearings into the House committee that probed the attacks, while Trump has so far stuck to his promise to pardon the rioters who took part in the 2021 attacks as soon as he takes office.

We hope The Ink will be essential to the thinking and reimagining and reckoning and doing that all lie ahead. We want to thank you for being a part of what we are and what we do, and we promise you that this community is going to find every way possible to be there for you in the times that lie ahead and be there for this country and for what it can be still.

What’s on display today, then, is the vast gulf between two very different notions of understanding the past and of accountability itself. What looks like the regular operation of democratic institutions is, in fact, exhibit A in an argument against the possibility of reckoning in America.

The courts refused to reckon with Trump’s transgressions in a series of decisions last year, and whatever the sentiment drove American voters, the electoral results demonstrated that the majority didn’t feel strongly enough about accountability to provide it at the polls.

Congress was unable — and unwilling — to exercise its responsibilities to preserve democracy. Attempts at the state level met with failure on court review, or have been abandoned as the clock’s run out. The once-and-future president returns to office having evaded substantive responsibility for everything that happened during his first term in office — and he’ll be doing this in a nation that’s shown — with major donations by captains of industry and the tacit endorsement of major news organizations — that it’s ready to be far more compliant this time around.

Harris presiding over the smooth transition to an emboldened, oligarch-powered MAGA movement calls to mind Al Gore gaveling out objection after objection from Democratic members of the House, whose objections — as the evidence has borne out — were more legitimate than any of the Republican grievances expressed in 2020. The country may have put those roiling tensions aside during the Obama era, and again through the supposed return to normalcy of the Biden years, but despite the smooth functioning of the machinery of government this time around, the revolt against the future — and against accountability — is back again with a vengeance.

Four years ago, The Ink asked the civil rights lawyer Sherrilyn Ifill, “Are we a culture that doesn’t do accountability anymore? That doesn’t do reckoning?” And institutionally, at least, we’ve gotten an answer to that question. But if elected representatives, the courts, and ultimately the voters refuse to hold Trump accountable, is there still a way forward, at least in the long-term struggle for justice?

Ifill answered this way, in part:

I think it’s a great question. And the answer is in the “we.” We are also capable of convening our own accountability structures. And if we are unsuccessful in compelling the government to do it or in compelling institutions to do it, then I think there are other platforms. There can be state truth and reconciliation commissions. There can be city truth and reconciliation commissions. There can be commissions that are created by distinguished citizens who choose to investigate and conduct hearings and present information publicly and use the Freedom of Information Act to present the data that they can get. Nothing stops us from truth-telling.

When we talked to legal scholar David Kaye at the end of last year, he made a similar point. Just because the United States hasn’t managed to build an official human rights infrastructure at national scale doesn’t mean it’s impossible, even now. It may be more critical than ever.

I am an optimist, but I’m really worried about the next four years. And the thing that I’m most worried about the next four years, is the impact on humans, on individuals. But I’m also really worried about the future resilience of civil society. We need to build resilience because whether it’s deportations, decimation of the media, the advance of state propaganda, or defamation cases against the opposition, we need to protect against that.

We need to maintain civil society space. This could be a place to continue to advocate and to identify and maybe eventually to generate power for those who care about human rights, left and right. That’s the objective.

As Ifill pointed out, ultimately it’s up to the public to recognize and tell the truth, and while that may be more difficult in the coming years given the torrent of untruths that the incoming administration is likely to unleash after January 20, it’s incumbent that Americans build the kind of civil society that enables truth-tellers to keep accounts for the future.

Your support makes The Ink possible, so if you haven’t joined already, we’d be honored if you’d become a paid subscriber. When you do, you’ll get access each week to our regular posts and our interviews with the most thoughtful people out there — and you’ll be able to join the conversation in our comments section.

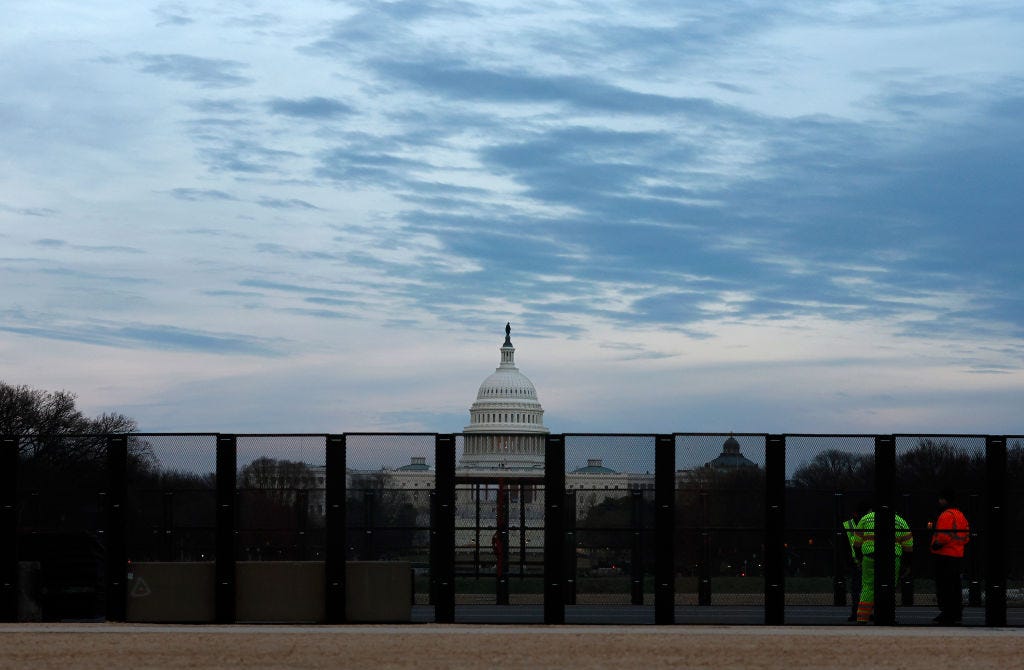

Photo by Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

This post was originally published on The.Ink.