Ultrabulk, trans-oceanic cargo ship, Astoria, Oregon. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

Okay, maybe you do read these in the newspaper, but not as much as you should.

1) The dollar’s status as the leading reserve currency does not mean we have to run a trade deficit,

2) There is no direct relationship between the budget deficit and the trade deficit,

3) The explosion in the size of the trade deficit at the start of the century cost millions of manufacturing jobs,

4) The trade deficit is considerably smaller today than it was two decades ago,

5) Manufacturing jobs are not necessarily good jobs. Unions made them good jobs, not the factories.

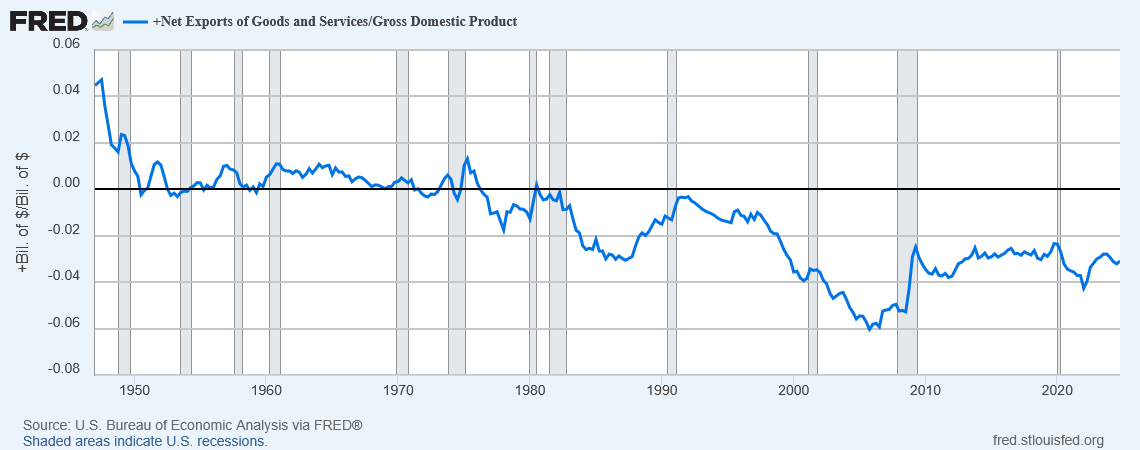

The graph below shows the trade deficit back to 1947. It helps to make several of these points.

The Dollar as a Reserve Currency and the Trade Deficit

Many people claim that the United States has to run a trade deficit in order to supply the rest of the world with dollars, since it is the leading reserve currency in the world. This story is badly confused for two reasons.

First, while the dollar is the leading reserve currency, it is not the only reserve currency. Euros, British pounds, Japanese yen, and even Swiss francs are held as reserves by central banks. Most reserves are in the form of dollars, but these other currencies can be and are used as alternatives. The same is true for international trade. While most trade is carried through in dollars, companies and countries use whatever currency they find convenient, and often this is not dollars.

The other point of confusion is that the United States can provide other countries with dollars without running a trade deficit. This can be clearly seen in the years from 1947 to 1973, when the US ran modest trade surpluses in most years. During this period, the United States literally was the world’s reserve currency, with other currencies being legally pegged to the dollar.

They were able to acquire dollars though US foreign investment. If the US is investing more abroad than foreigners are investing here, then we will be supplying the rest of the world with dollars without running a trade deficit.

The Relationship Between the Budget Deficit and the Trade Deficit

Back in the 1980s and early 1990s it was common to refer to the budget deficit and trade deficit as “twin deficits.” The argument was that the budget deficit meant that we had insufficient national savings and therefore had to borrow from abroad, which implied a trade deficit. (I’m skipping some steps, but that was the underlying logic of the argument.)

This argument never fit the data very closely even in those years. The trade deficit was brought down from 3.0 percent of GDP in 1987 to less than 0.4 percent of GDP by the fourth quarter of 1991, even as the budget deficit was increasing as a share of GDP. The story fell apart completely in the late 1990s as the trade deficit expanded to almost 4.0 percent of GDP even as the government was running a budget surplus.

The story here was the value of the dollar against other currencies. In 1987, the Reagan administration negotiated with our major trading partners to bring down the value of the dollar against the German Mark, the French franc (this was pre-euro), the British pound, and the Japanese yen. This process proved successful, as the dollar fell in value against these currencies and the trade deficit fell with it.

The trade deficit remained relatively low until the mid-nineties, when Robert Rubin replaced Lloyd Bentsen as Clinton’s Treasury Secretary and adopted an explicit high dollar policy. They put meat on the bones of this policy in the East Asian financial crisis where the I.M.F. insisted that the fast-growing East Asian countries pay off their debts rather than get a partial write-down. This meant lowering the value of their currencies against the dollar, so that they could run large trade surpluses.

The harsh I.M.F. policy also prompted other developing countries, including China, to accumulate as many dollars as they could as insurance, so that they would not face the same fate as the East Asian countries. This meant keeping down the value of their currencies against the dollar. China was the most important country accumulating large quantities of dollars, but many other developing countries were following the same path. In the first years of the new century, the trade deficit expanded further, eventually peaking at over 6.0 percent of GDP in the fourth quarter of 2005.

The Tale of Two Graphs: The Trade Deficit in the 00s Cost Millions of Manufacturing Jobs

Many economists claim that we lost manufacturing jobs due to productivity growth and that the trade deficit had little or nothing to do with it. They show this point with a graph that shows manufacturing jobs declining as a share of total employment in more or less a straight line from 1970 to 2010.

I counter this with another graph showing the absolute number of jobs in manufacturing. While this fluctuates with the business cycle, there is only a modest downward trend from 1970 to 2000. From 2000 to 2007, before the Great Recession, we lost 4 million manufacturing jobs, or one quarter of the total. We lost another two million in the recession, although we later got roughly half of these jobs back.

It is dishonest to claim that the loss of manufacturing jobs in the 00s was just due to productivity. It’s pretty odd that productivity just happened to cost so many jobs when the trade deficit was exploding but not in the prior 30 years or subsequent 15 years. States in the Midwest, like Ohio, Wisconsin, and Michigan, lost 30 to 40 percent of their manufacturing jobs. This was a huge deal to the affected workers and their communities. We need to recognize this fact. Also, it could have been avoided; there was nothing natural about the pattern of globalization we followed.

One last point, the productivity folks are right in the sense that even if we got the trade deficit to zero, we would only see a modest increase in the number of manufacturing jobs. By my calculation, it would go from 8.0 percent of the labor force to 9.0 percent of the labor force. That is not exactly transformational.

The Trade Deficit Has Fallen Sharply in the Last Fifteen Years

I realized that there is enormous confusion about the size of the trade deficit when I saw a New York Times article earlier this week that told readers the trade deficit was $1.2 trillion and that this was record high. Both parts of this story are wrong. The trade deficit was actually $900 billion last year. The $1.2 trillion figure is only for trade in goods. The US runs a large surplus on trade in services — items like insurance, shipping, and payments for intellectual products. There is no obvious reason to exclude services from the story.

Also, the fact that the deficit is not anywhere near a record when measured as a share of GDP (the only reasonable measure), is also important. Calling it a record implies that the deficit is large and growing, which could seem scary. In fact, it is roughly half the size of its peak in 2005. Insofar as we see the trade deficit as a problem, it is half as large a problem as it was twenty years ago.

Unions Made Manufacturing Jobs Good Jobs, Not the Factories

In 1980, manufacturing jobs offered better pay and benefits, especially for non-college educated workers, than other jobs. This is no longer true. Most or all of the manufacturing wage premium has been eliminated.

The obvious explanation for this fact is the decline of unionization in manufacturing. In 1980, almost one-third of manufacturing workers belonged to a union compared to just 15 percent in the rest of the private sector. Last year, these numbers were 8.0 percent for manufacturing compared to 6.0 percent for the rest of the private sector. That 2.0 percentage point gap does not make much difference in terms of pay and benefits for workers in manufacturing.

This means that there is little reason to prefer manufacturing jobs to jobs in health care, transportation or other sectors. If we want workers to have good-paying jobs, we should want to see more union jobs, whether in manufacturing or any other sector.

Facts Beat Confusion

There is much nonsense in debates on trade — and not all of it is coming from the Trump administration. There is plenty of room for disagreement on policy going forward, but the disagreements will not change these five facts.

This first appeared on Dean Baker’s Beat the Press blog.

The post Five Facts About Trade You Don’t Read in the Newspaper appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.