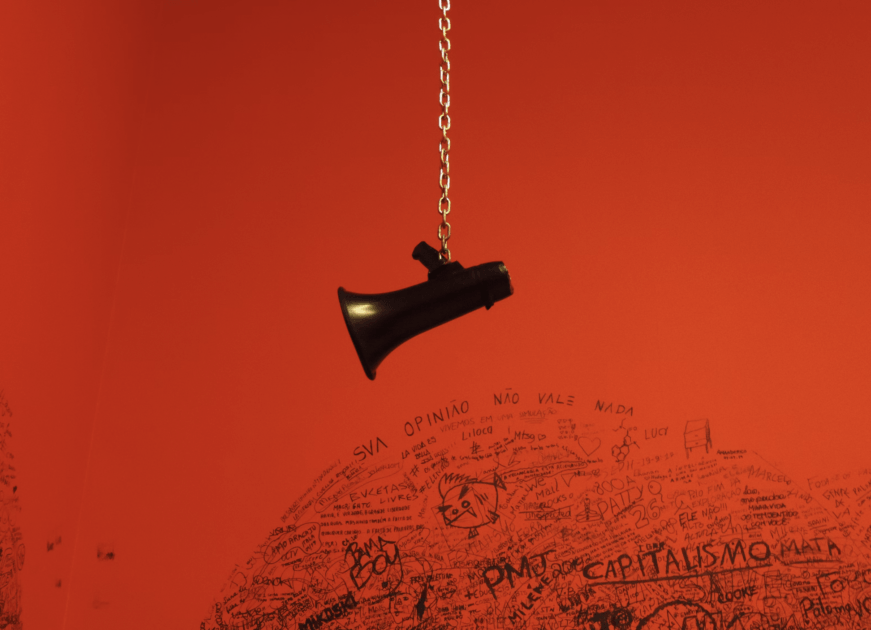

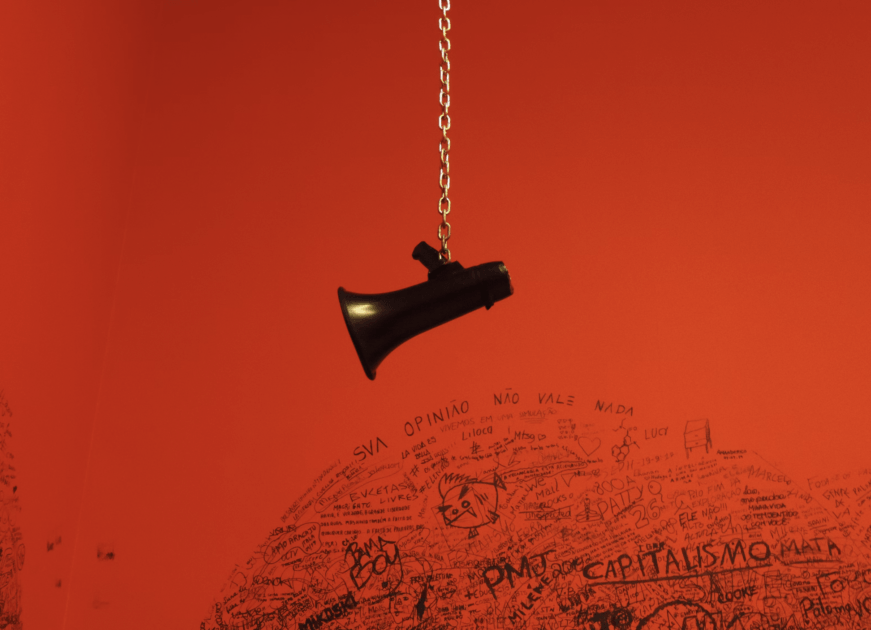

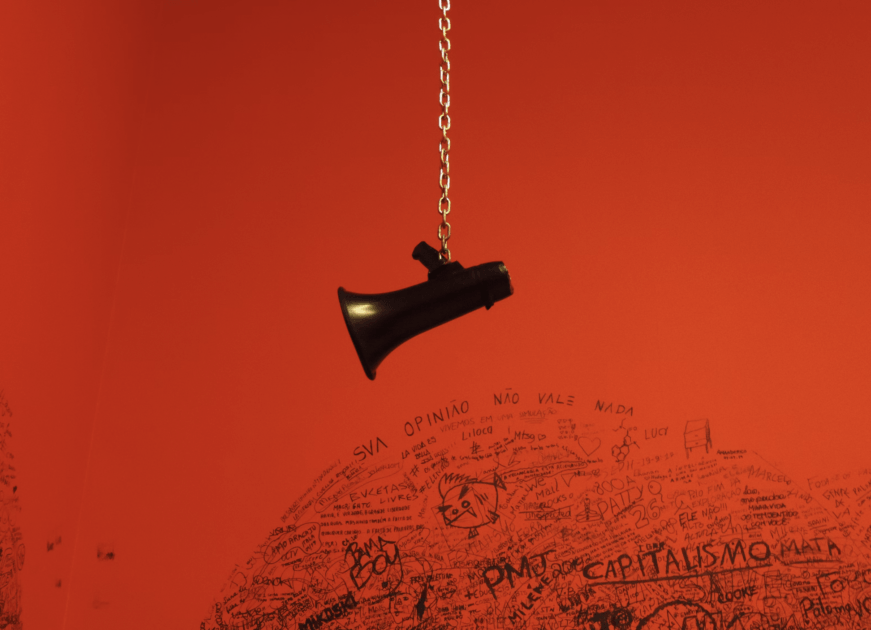

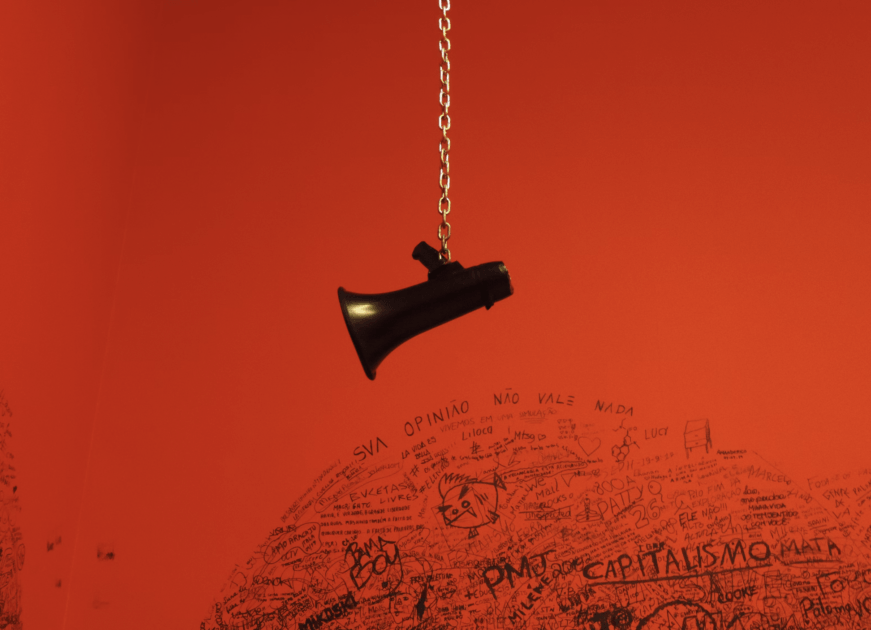

Photo by Ana Flávia

How important are voices? President Trump officially fired the head Archivist of the United States, the director of an agency considered the nation’s recordkeeper. Historical records are the voice of a country. Trump’s potential altering of history could change the national voice. The death of Pope Francis is another example of the importance of voice. “Francis’ death silences voice for the voiceless,” headlined an article by Jason Horowitz in the New York Times. “The least among us have lost their voice,” a soup kitchen manager in Rome was quoted in the same article.

Besides changing or losing voice, there is also fear to use one’s voice to describe what is taking place in the United States. Senator Lisa Murkowski, one of the few Republican dissenting voices in Washington, recently told a gathering of non-profit leaders in her home state of Alaska; “We are all afraid,” Murkowski said. “It’s quite a statement. But we are in a time and a place where I certainly have not been here before. And I’ll tell ya, I’m oftentimes very anxious myself about using my voice, because retaliation is real.” Wesleyan University President Michael Roth made a similar comment about why more university leaders are not signing a statement opposing Trump’s assault on academic freedom; “I asked a lot of people to sign, and many people said: ‘I can’t sign. I’m afraid.’”

Faced with changing history, lack of voice and fear, one looks for a different perspective on sound and voice. An unusual exhibit at the International Committee of the Red Cross’ (ICRC) Museum in Geneva highlights the diverse roles of disparate sounds and voices. “Sounds…maybe something passed into the background compared to the visual,” the curator Elisa Rusca explained to me, “But that doesn’t mean they have as much strength, on the contrary, sometimes it’s because of the sound that an image takes on its full power.”

The exhibit “Tuning In – Acoustics of Emotion” focuses on tuning in to non-traditional sounds and voices. “Methodologically,” Rusca said, “the exhibition is indeed an Atlas where the audience can move freely and enter all these different worlds I created, and each world is a different frequence.” Included in the different frequencies are sections on voice and memory, sound at the Museum, emotions and voice, and voice and engagement.

The interdisciplinary exhibition is a welcome relief for those tired of or overwhelmed by current events and too much noise who wish to hear other voices, other sounds. It uses the ICRC’s and IFRC’s audio archives as well as contemporary artists to deal with emotions and sound in an innovative manner; “[M]y wish was to avoid the noise, and to celebrate the richness of diversity,” Rusca wrote. The curator prepared the exhibit with the Swiss Center for Affective Sciences (CISA) at the University of Geneva.

By linking sound and voices with humanitarian action, the exhibit highlights the role of emotions, something that is far from obvious in a traditionally visual museum dedicated to humanitarian action. “These are voices, official speeches, but also delegates’ reports, briefings after missions,” Rusca explained. “These are direct shots during situations, crises, but also emergency messages or health radio broadcasts created by national societies.”

Sounds and voices appeal to our emotions. But is there a role for emotions in our intellectual reasoning? How important are emotions in our decision-making process? The eminent philosopher Martha Nussbaum thinks they are very important. She wrote in her 2001 book Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions: “Instead of viewing morality as a system of principles to be grasped by the detached intellect, and emotions as motivations that either support or subvert our choice to act according to principle, we will have to consider emotions as part and parcel of the system of ethical reasoning.”

What questions about our “ethical reasoning” are raised in the “Tuning-In” exhibit? For example, one part of the exhibit shows songs being recorded in response to the 1983-1985 Ethiopian famine. Musicians and celebrities recorded “humanitarian songs” such as Do They Know It’s Christmas? (Band Aid, United Kingdom), We Are the World (USA for Africa, United States of America), Éthiopie (Chanteurs sans frontières, France), Nackt im Wind (Band für Afrika, Germany) and Les yeux de la faim (Fondation Québec Afrique, Canada). What is striking is how quickly the recordings were organized because of the sudden famine as well as the dichotomy between the professional recording studios and the actual situation of the famine victims in Ethiopia.

Several contemporary artists are also featured, such as Dana Whabira and Suzana Sousa. Their conversation on the connection between Ubuntu, African philosophy and love started when Whabira discovered that the word love was not found in the ICRC data base. There is even a soundless exhibit about sign language. Christine Sun Kim’s series of videos produced in collaboration with Thomas Mader, explores the expressiveness of American Sign Language, combining facial expressions and hand gestures.

The Director of the ICRC Museum, Pascal Hufschmid, observed that “Sound is something that penetrates us, it’s something that completely takes us. All of a sudden, if we take this step aside, and look at sound critically and question what the sound conveys and carries with it, it really allows us to better understand the issues and the complexity of humanitarian action.”

More than just allowing us “to better understand the issues and complexity of humanity action,” an exhibit about sound and voice allows us to step back from the enormous noise that now clutters our thinking. Trump and Company are omnipresent to such an extent that we must constantly struggle to find the right descriptive words to accompany our emotional revulsion.

The political has become the psychological. We are living through a national if not international mental health crisis. Nussbaum was spot on; “we will have to consider emotions as part and parcel of the system of ethical reasoning.” Trump is more than a threat to democracy and the Constitution; he is psychologically disruptive, destabilizing and distracting. Historical allies become enemies, yesterday’s executive order is put on pause, what was said before is no longer valid today. Even historical records in the National Archives can be altered. The traditionally dependable Uncle Sam can no longer be trusted. Our “system of ethical reasoning” needs serious updating.

The ICRC Museum exhibit “Tuning In – Acoustics of Emotion” is a welcome reminder of the importance of sound, voice and emotions. Murkowski’s and Roth’s comments are chilling indications of where we are heading and the necessity of finding new voices and new sounds to replace the deafening noise and sounds that engulf us. The exhibit suggests it’s imperative to tune in to different sounds and voices to find our way out of this emotional tsunami; and that you don’t have to turn on to tune in, nor drop out after tuning in.

The post Sounds and Voices in a World of Deafening Noise and Fearful Silence appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.