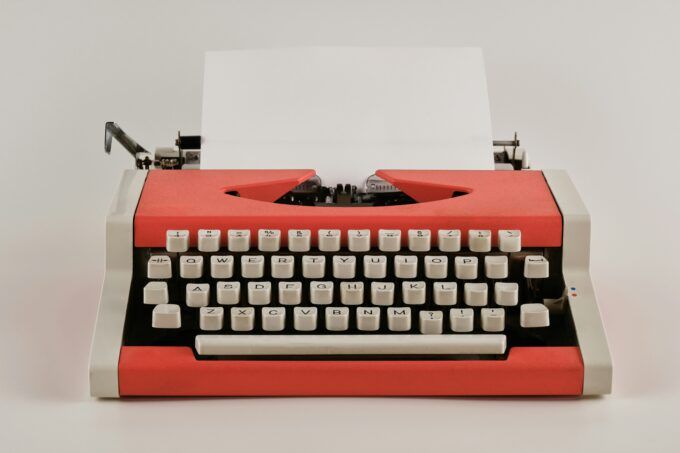

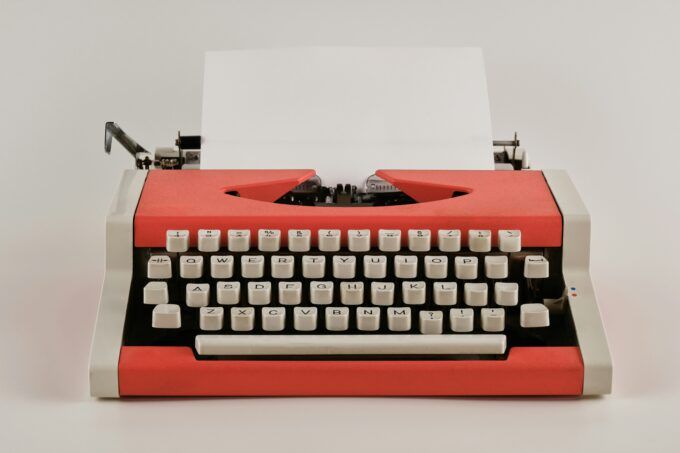

Image by Andrej Lišakov.

Thorne Dreyer, Notes from the Underground: 77 Articles that Bring the Past to Life. Austin: New Journalism Project, 2025. 476pp, $27.00

In the days of Campus Movement yore, i.e., the 1960s-70s, Austin, Texas, yielded nothing to San Francisco, Santa Cruz, Madison, Wisconsin or Burlington, Vermont. Its claims upon bohemianism and political resistance had a unique flavor, to be sure. Major university town and state capital, it departed from the other protest-heavy places in one key respect: it was surrounded by Texas.

The flavor stood out by itself. If left-wing prairie radicalism once prompted an Oklahoma socialist movement larger by proportional vote than anywhere else in the country, a lot of time had passed. And yet, at any national meeting of radicals, Austin men and women, mostly youngsters, prided themselves on their distinctive sensibilities. And their responsibilities: by the middle 1960s, Austin stood not far from major Army camps training young men to go to Vietnam. Thus the GI Coffee House movement, the key connection of the working class and the antiwar movement.

Legendary underground newspaper The Rag—in many ways the most important of all the unofficial press that reached millions of young readers with alternative views of war, politics and culture— found a ready niche here. Or rather, as a founding editor and the long-run project savant Thorne Dreyer says, the niche was created and sustained through herculean efforts. Things never happen by themselves, especially when funds are rare and dependent upon political movements of resistance.

This astounding book offers a record of the times far beyond the underground press that tanked by the end of the 1970s. The Rag found new forms of communication after its print format death. It operated for decades online and continues now as a radio feature from Austin, with some of the old hands still at the wheels of information and insight. The last regular journalistic piece here ends in 2014, but the “Rememberances” of the vanished comrades and the last salutes to Dreyer and his work offer some important addenda: people pass but the work continues.

The bulk of this very bulky volume is about radical journalism almost as much as about the world seen by the radical journalist. I had not known that Dreyer, a Texas boy and son of a prominent Houston newspaperman, aspired to be an actor before turning to his life’s work in 1966. The very first pieces in the book establish the tone of his keen and also lean prose thereafter: confrontations of military and pro-war political authorities by young radicals on campus and off, seen from the newspaper office as organizing center. In other words, his journalism was a political project as it could hardly be for anyone in the commercial press. He wastes no adjectives and indulges in no flowery prose. Every sentence counts, and a great many are also fun to read or read again now, looking back on a lively time. Especially to be noted: a tale of Marines attacking SNCC workers and anti-war activists at Hermann Park in Houston; Dreyer’s unique coverage of the massive March on the Pentagon; “A Comprehensive View: The Movement and the New Media,” and finally, “Under Siege: Space City! And the Nightriders.”

Dreyer describes the rise of the underground press from a few papers, very notably the Rag itself, into a national network of hundreds of local efforts, some crudely written or printed, some highly sophisticated in every professional respect except….financed by nobody in particular, hawked by volunteers in public venues (starting with the campus), and staffed by amazing amateurs who nevertheless taught themselves to create the most lively and compelling journalism of the age. And not only journalism. Not since the Yiddish-language press of the 1890s had radical papers carried poetry on the first page! Never had a leftwing paper boasted such new and rebellious, wildly creative comic art. And so on.

Dreyer made himself an insider in the small crowd that created the Liberation News Service, a shoestring operation that circulated important journalism and entertaining features free of charge each week. The Rag boasted comic artist Gilbert Shelton and his Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, by the 1970s-80s a hit across large parts of Europe. A graduate school dropout who found his way to San Francisco (where he published and largely drew my own initial entry into comic art, Radical America Komiks, in 1969), Shelton popularized the Austin Ambience, if such a thing existed.

Dreyer moved on himself, for a few years, to Space City!, the underground newspaper counterpart in Houston, his own home town. He also toured widely, capturing news of the left, mobilization and repression, across the country. He met and interviewed the day’s radical celebrities, including Jane Fonda, later Yippie leader Jerry Rubin, TomHayden, Judy Collins, NFL star Dave Zirin and inevitably Texas’s own Kinky Friedman, among others.

Building a community of protest around itself, Space City! managed to survive military-style assaults upon its headquarters by the KKK and others, and ended only in the political exhaustion of the staff. Perhaps, looking back, the great virtue of all the Texas Left was to move on, change forms, find newer generations more usually organized around culture than politics as such. Even Houston, more than college-town Austin, a real Southwestern megalopolis, had a bohemian neighborhood by the 1970s-80s, where artists of various kinds flourished, most especially but not only musicians and singers. Meanwhile, Austin, like Madison and so many other places, has faced extreme gentrification from incoming capital, creating an urban world in which low rents and lazy bohemian afternoons seem to be part of urban memory. And yet Thorne Dreyer persists! And will be heard, we hope, for a long time yet.

The post The Sage of Austin, Texas appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.