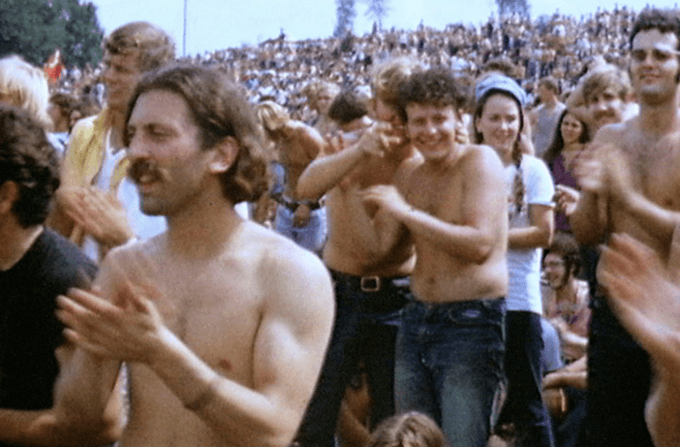

Woodstock, 1969. Wikipedia.

In most histories, the counterculture of the 1960s is usually considered a youth culture. In terms of sheer numbers, this is true, given that the majority of its adherents were people under the age of thirty. However, it was those that some like to call elders that inspired the culture and arguably led the way—if anyone led at all. In this regard, it wasn’t just the Beats whose distrust of authority and doubting eyes informed the movement the mainstream called hippies. No, it was also those who came before—poets like Kenneth Rexroth, Robert Duncan and various surrealists and artists such as the Sausalito Six and Philip Lamantia. As author Dennis McNally writes in his new history of the counterculture, titled The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies and Created the Sixties, the birthplace of this movement was San Francisco. However, to be fair-minded and honest about the movement itself, McNally bounces between San Francisco, London, Los Angeles and New York in a work that unfolds into a comprehensive, entertaining and impressive history of the sixties counterculture.

Weaving his story on a loom composed of rebellious artists, unruly poets, rock, blues and folk musicians, instigators, agitators and actors unwilling to stick to the drama on the stage, McNally takes the reader into an enchanted world where freedom and love were prized, redefined, and celebrated. And attacked by those who feared such a world. Then, of course, there were the drugs: marijuana, amphetamines and LSD. The former were old timers in the history of mind expansion and mood modification. Marijuana went back to millennia before Christ, while amphetamines has been discovered and used for most of the twentieth century. LSD use, on the other hand, had been limited to a relatively few medical researchers, society types and a few artists since Albert Hoffman’s discovery of its hallucinogenic properties in 1943. It would be the mass production and popularization of LSD in the US and Europe that would do more than perhaps anything else to create the mindset enabling the exponential expansion of the countercultural ethos.

McNally’s telling is both linear and otherwise. Certain events that seem crucial to the existence of what became the counterculture, such as the civil rights movement and the reaction to McCarthyism and the Red Scare, are placed appropriately in the book’s timeline. So, too, are the beginnings of City Lights Books and publishing. As one reads on, other events and personalities appear in mostly chronological order. At the same time, the author incorporates spiritual and intellectual trends—phenomena that tend to be more difficult to pin down to a particular moment—and discusses their influence and how they became part of the countercultural zeitgeist.

Familiar names appear throughout the text, familiar and maybe famous: Ken Kesey, Bob Dylan, the Grateful Dead, Joan Baez, and Bill Graham, the Living Theater, Julian Beck and Judith Molina, to name a very few. Likewise, influential persons in their field are discussed, including the composers Pauline Oliveras and Terry Riley; the Diggers Emmett Grogan and Peter Coyote; LSD chemist and soundman extraordinaire Bear Owsley Stanley and the filmmaker savant Harry Smith. The circumstances of these appearances, while often outside of how one might have previously conceived this group of individuals (or any of the others mentioned and discussed), only adds to the myth of the sixties. That myth is of course the spawn of any number of the truths revealed, realized and redeemed in the times of which McNally exposits. There are dozens more whom McNally kindly lists as an appendix of sorts towards the back of the text. Then there are the millions who carried the spirit onward and outward into the world and forward through time. The latter might include you.

Among many other possibilities, The Last Great Dream can (and should) be considered as a testament to the power of art, music, speech and the word. Simultaneously, it is also a history of the repression of all of the above. From the McCarthyite attacks on left political thought as represented by the House of Unamerican Activities Committee(HUAC) hearings in San Francisco’s City Hall to the persecution and prosecution of comedian and social commentator Lenny Bruce, the authorities of the state as represented by the police and the courts were often if not always unforgiving in their repression. Whether they were attempting to criminalize art or words or actually criminalizing mind expansion aids (LSD was legal until 1966), the men in the gray flannel suits and their accomplices in the churches and in uniforms seemed to be everywhere, banning works, attacking gatherings and arresting musicians and their audiences. Nonetheless, the times moved forward, over, under, sideways and up, as if the gods themselves were involved. McNally’s narrative enhances that very prospect, as only a history written by one who knows intuitively of what he writes. Who but someone with such an understanding would call John Coltrane’s 1964 album A Love Supreme “one of the great works of western religious music” and go on to suggest that perhaps Bob Dylan heard Coltrane’s incantation as he was recording the song “Masters of War” on his album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan?

I know the history McNally discusses in this text, but like all history, every time it is told one learns something new of that history. Dennis McNally’s new book about the birth of the 1960s counterculture verifies this truth once again. When a writer of McNally’s abilities and knowledge is the one providing the history, the reader is in for an unforeseen delight, an excursion beyond the norm and outside the predictable. Connections are made which one might not have made before; questions arise which did not consciously exist prior to the reading, all while the reader hopes the book never ends.

However, since it does end, perhaps the suggestion made at the end of every broadcast by the counterculture radio commentator (KSAN and KFOG) Scoop Nisker applies—”If you don’t like the news, go out and make some of your own.” If you don’t like the culture around you now, go out and create one of your own.

The post Setting the Controls for the Heart of the Sun appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.