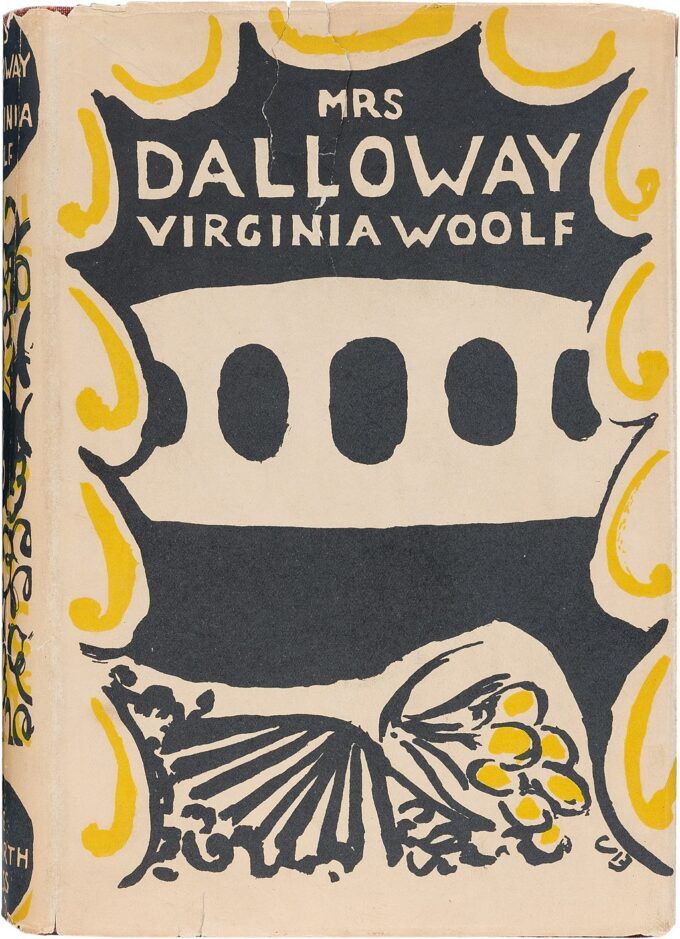

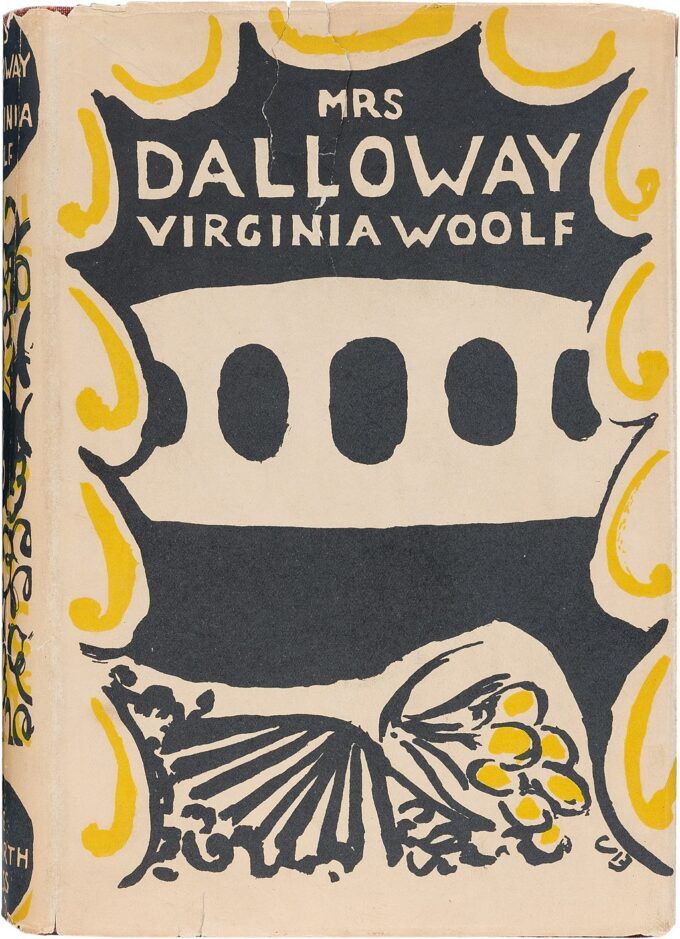

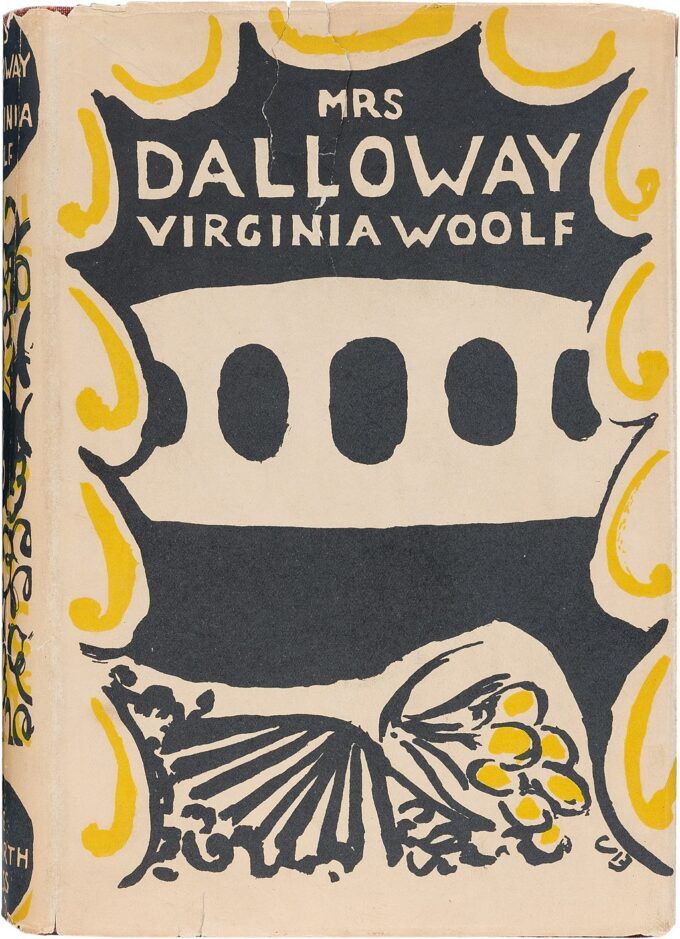

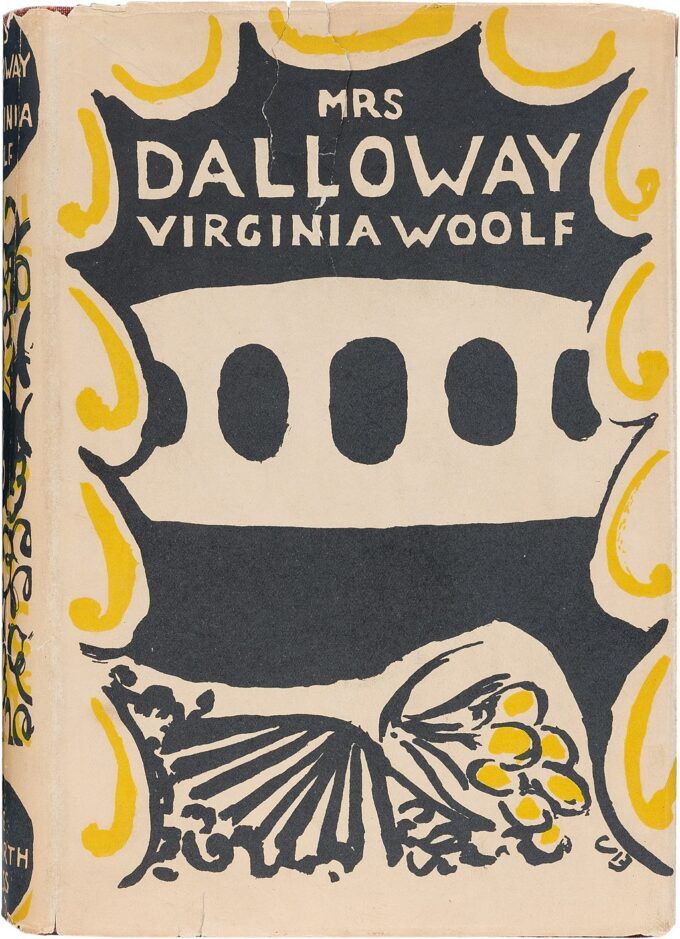

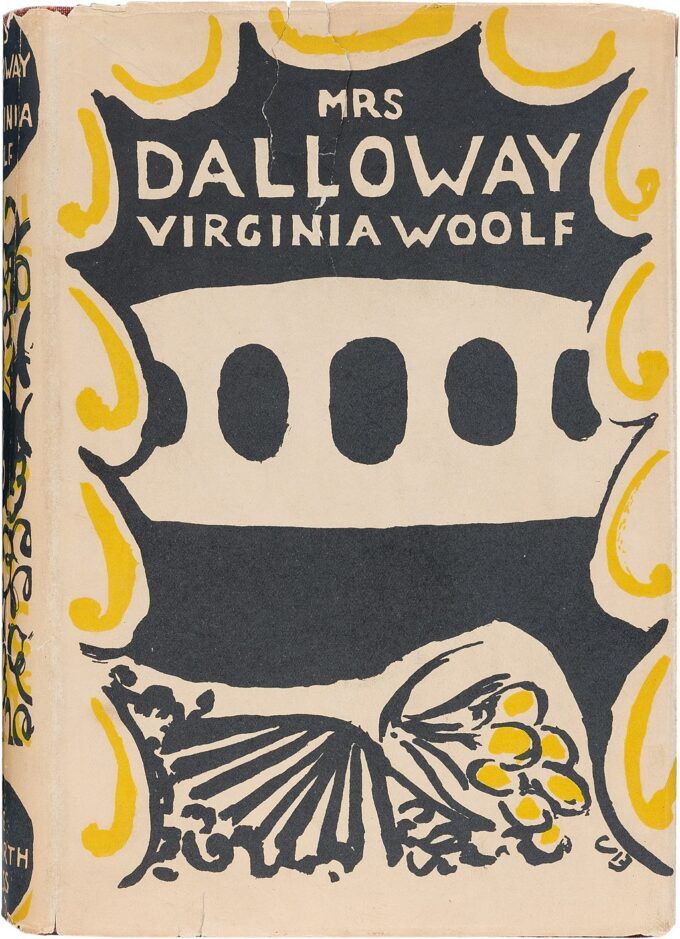

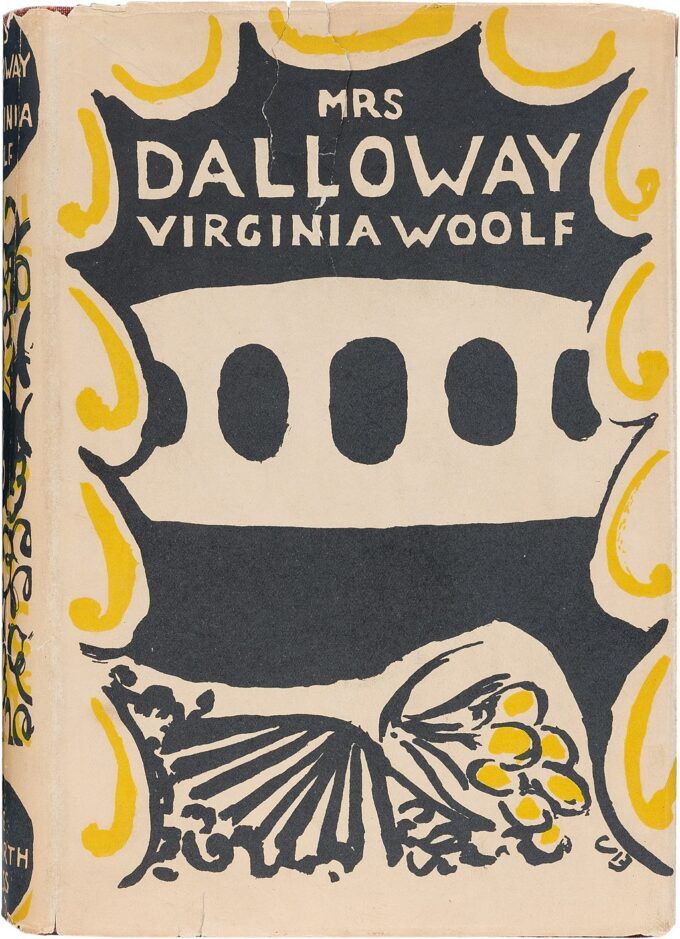

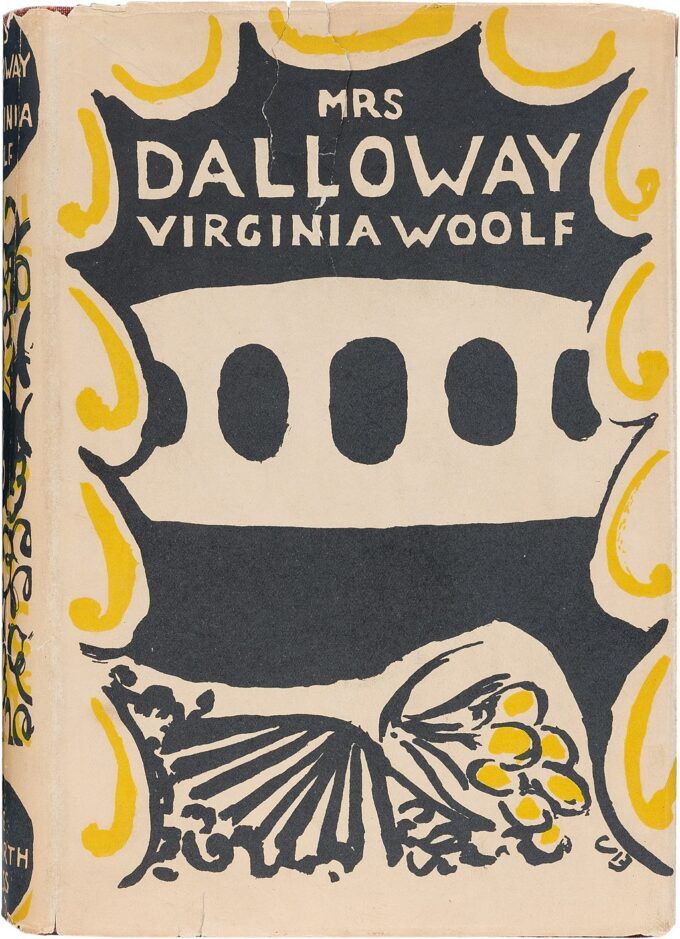

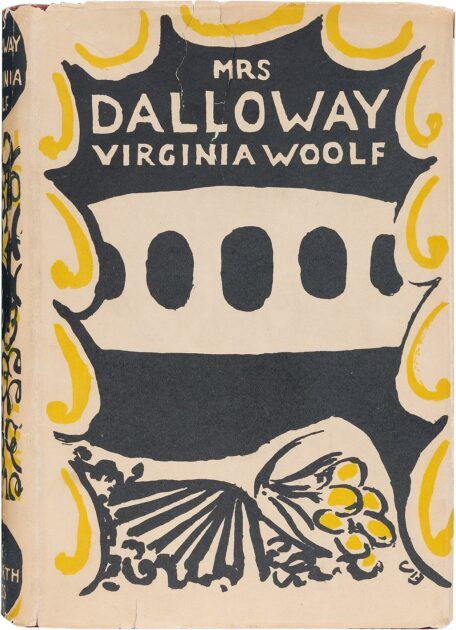

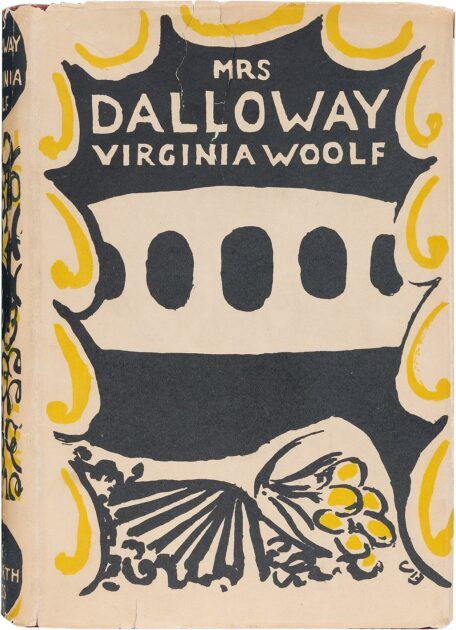

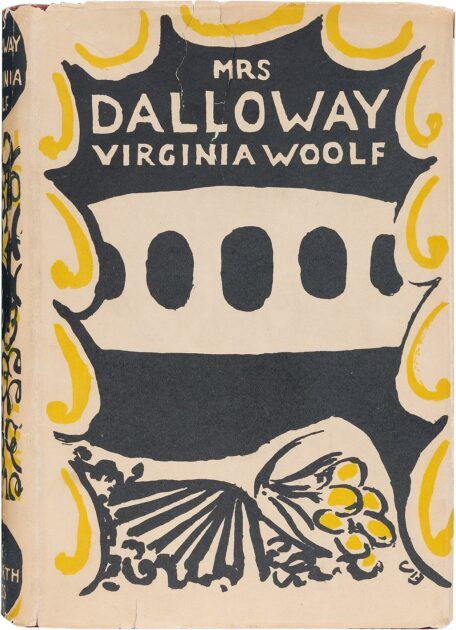

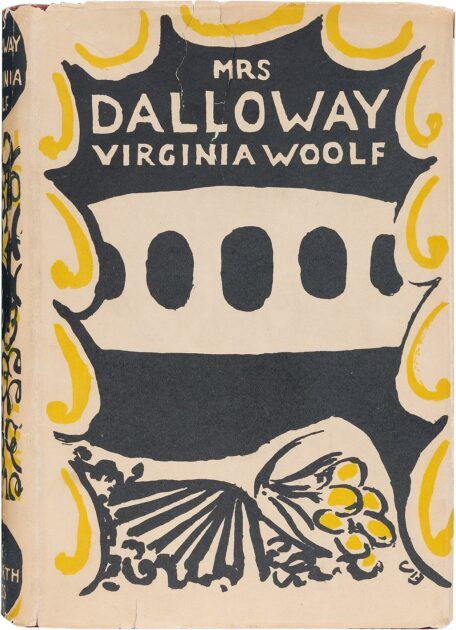

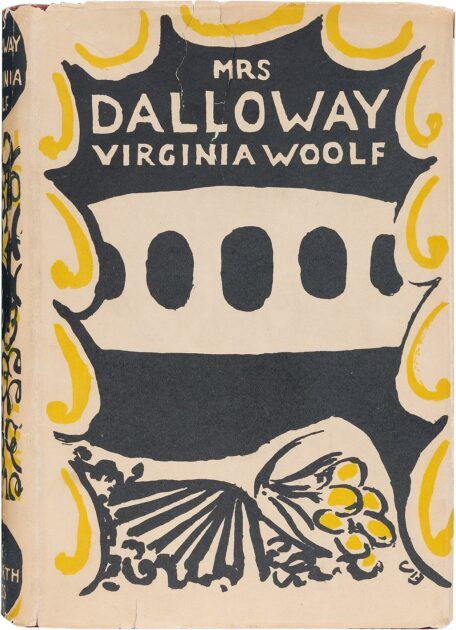

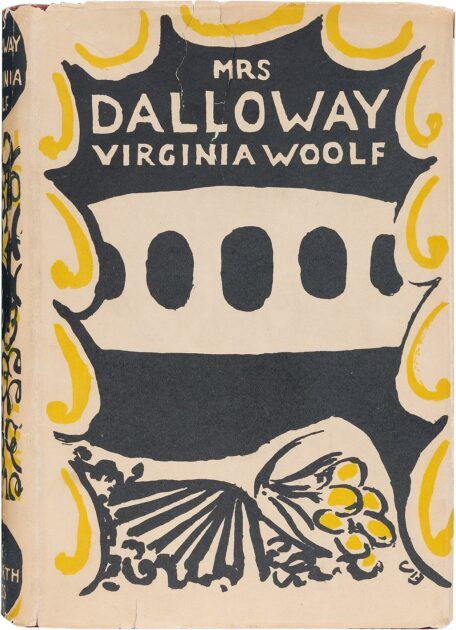

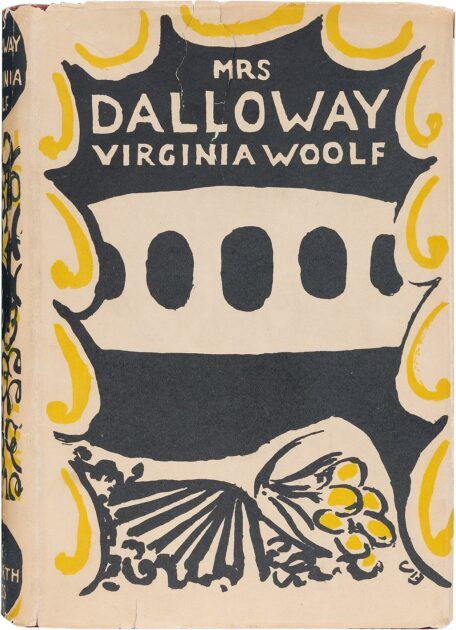

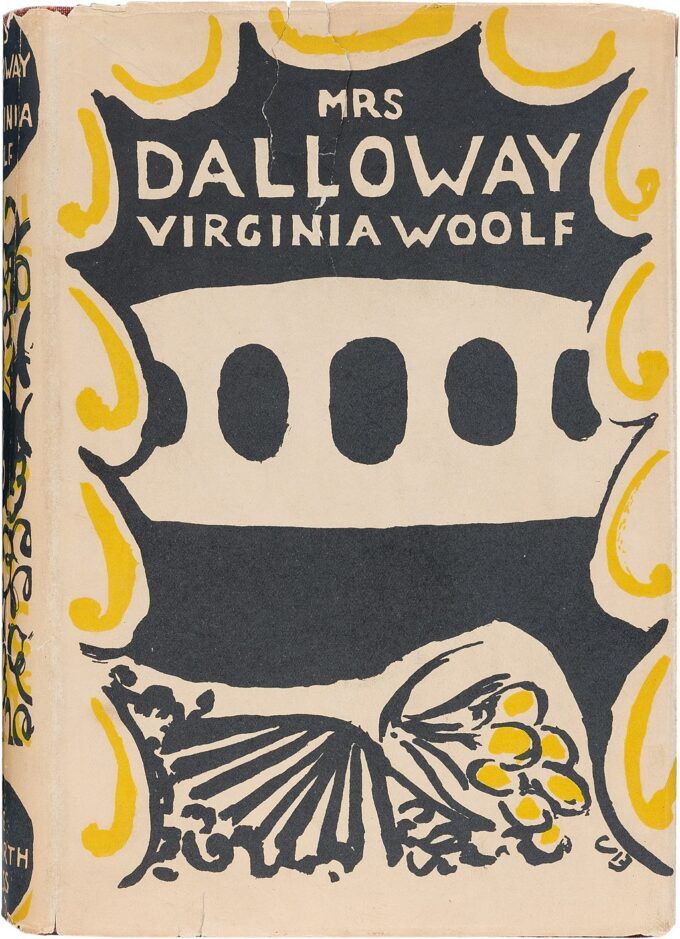

Original cover art for Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway.

Virginia Woolf didn’t realize when she began to publish her own work more than 100-years ago that she would birth a cottage industry that would put all her writing – letters and diaries as well as essays, novels and short stories—into print, and that would be read and studied around the world. No one was more scribacious than Woolf and no one was more devoted to the cause of women writers than she. The novelist Michael Cunningham, author of The Hours, calls her “a goddess” and himself “one of her acolytes.” Other authors and critics have been no less effusive.

In Three Guineas—while all Europe hurtled toward WWII— Woolf wrote defiantly, “As a woman, I have no country. As a woman I want no country. As a woman my country is the whole world.” The rise of militarism and fascism (as well as her own depression) seems to have driven her to suicide at the age of 59. She harbored and expressed some of the prejudices of the British upper class into which she was born and bred, called herself a “snob” and didn’t always transcend her snobbery.

Unlike Emily Brontë and her literary sisters, Charlotte and Anne, whose books first appeared in print under the male pseudonym, Currer Bell, and unlike Mary Ann Evans who published under the pen name George Eliot, Virginia Woolf published her work under her real name. The world of books, authors and editors, and the status of women in British society had come a long way from the days of the Brontës in the early 19th-century, when a young woman might aspire to earn a modest living as a governess, but to aspire to authorship was often deemed “unladylike.”

To write and publish under one’s own name, like “Mrs. Gaskell,” the author of North and South and Wives and Daughters as well as a biography of Charlotte Brontë, was to go against the grain. Mrs. Gaskell’s first novel, Mary Barton, (1848), was published anonymously. Virginia Woolf reaped the benefits provided by the pioneers of English fiction, from the Brontës, to George Eliot and Mrs. Gaskell. She acknowledged their influence.

Born in 1882, near the tail end of the reign of Queen Victoria— and for a brief time one of the last of the Victorian novelists—Woolf changed her early writing style and her outlook on the world at about the same time that the British Empire was fast failing. An ardent pacifist and passionate feminist, Woolf died in 1941, before she was recognized as one of the mothers of modernist fiction.

The seventh child of Julia Prinsep and Leslie Stephen, she was initially educated at home, attended King’s College London, advocated for women’s rights, and in 1912 married Leonard Woolf, a secular Jew who served the British Empire in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). He kept her alive and on track for decades.

Virginia and Leonard founded the Hogarth Press, which published her work, and the first edition of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. They also helped to give birth to the Bloomsbury Group, a literary and political circle whose members included the economist John Maynard Keynes, the novelist E. M. Forster, artist Vanessa Bell and biographer Lytton Strachey.

Woolf’s early, largely traditional work includes The Voyage Out (1915) and Night and Day(1919). Jacob’s Room (1922), which was influenced by post-impressionist painters such as Matisse and Cézanne, took her in a radically new and different direction. Still, it was not until the publication in 1925 of Mrs. Dalloway now celebrating its one hundredth anniversary, that Woolf perfected the stream of consciousness style for which she has been globally recognized. By calling her character “Clarissa,” Woolf no doubt wanted readers to think of Clarissa Harlowe, the protagonist of Samuel Richardson’s 1748 epistolary novel, Clarissa or, the History of a Young Lady, subtitled Comprehending the Most Important Concerns of Private Life.

Clarissa Dalloway isn’t young, but she’s a lady with a fascinating personal history and a complex private life that Woolf traces, and portrays bourgeois British society that surrounds her.

Often ignored during her own lifetime, it was not until the 1960s that Woolf’s work began to be heralded, widely read and made required reading in college literature courses. Feminist critics and advocates of the women’s liberation movements “discovered” her novels and her non-fiction, including the magisterial and influential book-length essay, A Room of Her Own in which she noted famously that to be a writer a woman needed “money and a room of her own.” An aunt left her an endowment of 500 pounds a year.

The Mississippi-born American fiction writer, Eudora Welty, expressed some of the enthusiasm for Woolf’s work in a 1981 Foreword to a paperback edition of To The Lighthouse (1927). Welty wrote that Woolf’s novel “is a triumph of wonder, of imaginative speculation and defiance.”

She might have said much the same about Mrs. Dalloway, which has slowly but surely become an enduring classic of 20th-century British literature that belongs on the same shelf along with James Joyce’s Ulysses and Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. Not surprisingly, Mrs. Dalloway has echoes of both Joyce and Proust. An avid reader and an astute book reviewer and critic, Woolf devoured and absorbed sections and some of the perspectives of In Search of Lost Time.

She also read and reread Ulysses (1922) which she described as “an illiterate, underbred book it seems to me: the book of a self-taught working man, & we all know how distressing they are, how egotistic, insistent, raw, striking, & ultimately nauseating.” That comment says more about Woolf’s elitism and snobbery— about workers and the Irish, as well as British subjects who weren’t educated at Oxford or Cambridge— than it does about Joyce’s novel. Perhaps she was jealous of Joyce’s fame.

Despite the rebuke, she borrowed from Ulysses, which takes place in Dublin, Ireland during one day, June 16, 1904, and that offers parallels with Homer’s The Odyssey. Woolf chose not to offer echoes of Homer or any other ancient epic, but like Joyce she opted for the Aristotelian unities of time and place.

Mrs. Dalloway is set in London, England, the city she knew as well as Joyce knew Dublin, on one day in the middle of June 1923, not long after the end of WWI, a traumatic event which casts a long dark shadow on the characters and the plot. For over two-hundred pages, the authors wanders in and out of the consciousness of her characters, especially Mrs. Dalloway’s. She also describes her impressions of people, streets, and automobiles as she wanders about London, and so the novel offers a complex multi-faceted portrait of the city and its citizens from all walks of life.

Ulysses takes place a decade before the start of WWI, though it was written after the start of the war and with the war in a rear view mirror as a catastrophe in the offing. Woolf took a different approach to the 20th –century. By setting her novel in the immediate aftermath of WWI, she was able to depict its deep and profound impact on British society and especially on one of the novel’s central figures, Septimus Warren Smith, a suicidal shell-shocked soldier. In today’s logo, he’s afflicted by PTSD.

Woolf also depicts Smith’s vain, pompous physician, Sir William Bradshaw, a doctor knighted by the crown and totally unable to rescue Smith or to ease his mental suffering. He’s a so-called “expert” without any redeeming and socially useful expertise.

Most of Woolf’s characters come across remarkably well as unique individuals and also as social types who are representative of the classes and castes to which they belong. Woolf gathers them together to satirize them without bitterness. Clarissa Dalloway is the shallow society hostess with the “most-ess” who attracts friends and acquaintances to her home. Smith is the foot soldier abandoned and forgotten by the powers-that-be whose power he has fought to preserve on the battlefield and in the trenches.

His ordinary British family name, “Smith,” marks him as common, while his given name, “Septimus,” singles him out from the crowd that attends Clarissa’s party, with the cream of London society, including the Prime Minister who makes a brief appearance. Clarissa’s party might remind readers of Gatsby’s parties in The Great Gatsby, published the same year as Mrs. Dalloway.

Woolf is adept at smooth introductions of her characters, moving them around effortlessly, and showing them interacting with one another. Septimus Smith’s suicide takes places at the same time, though not at the same place as Mrs. Dalloway’s party. He leaps to his death from a window, leaving his Italian-born wife Rezia, a 24-year-old hat maker, a widow. When Sir William tells Mrs. Dalloway at the party that a “young man had killed himself,” self-centered Clarissa thinks “In the middle of my party, here’s death.” Not what she wanted.

In the original version of the novel, Woolf planned to have Mrs. Dalloway commit suicide. The author clearly had suicide on her mind. She took her own life in 1941 at the age of 59 when she waded into the River Ouse in the UK with a large stone in the pocket of her coat that weighed her down in the waters. In a suicide note to Leonard which sounds self-deprecating, she wrote, “You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read, I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good.” She added, “Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer. I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been.” She signed the note with the capitalized letter “V.”

Among the most memorable characters in a large cast of characters in Mrs. Dalloway there’s first and foremost Peter Walsh, an ex-lover of Clarissa’s who wooed her before she married her rather drab husband, Richard Dalloway, a member of the Conservative Party in Parliament. Walsh is meant to be emblematic of the men who served the British Empire in India.

A scion of “a respectable Anglo-Indian family” that “for at least three generations had administered the affairs of a continent,” Walsh realizes that he has the sentiment of “disliking India, and empire and army.” Woolf seems to say that the British Empire was hollow at its heart.

Walsh and some of the other characters in Mrs. Dalloway are reminiscent of the figures in T. S. Eliot’s poem, “The Hollow Men,” which ends famously, “This is the way the world ends/ Not with a bang but a whimper.”

And yet, unlike “The Hollow Men,” and unlike The Waste Land, Mrs. Dalloway isn’t apocalyptic. Mrs. Dalloway’s world doesn’t end, and neither does she, though the novel depicts a world that’s dying, an empire in decline and a decadent aristocracy that’s fading into the pages of history. Mrs. Dalloway’s party is a sign of imperial failure not of rejuvenation.

Christopher Caudwell, the Marxist literary scholar who died in 1937 in the Spanish Civil War, might have made the novel a centerpiece in his trenchant collection of essays, Studies in a Dying Culture published posthumously in 1938.

If you have difficulty getting into Mrs. Dalloway and trouble reading it, as many readers do, try not to be discouraged. Like Ulysses and like The Waste Land it’s a difficult modernist work that repays attention and scrutiny.

When I was a student at Columbia College in New York in the early 1960s, Woolf’s work did not appear on any syllabus, her name sadly missing from discussions and lectures about British literature. That was the patriarchy talking. A younger generation of men (and women, too) have been attuned to Woolf’s genius.

Michael Cunningham, the author of the novel, The Hours, his homage to Mrs. Dalloway, writes that as a young man he tried and failed to read Woolf’s novel. “I couldn’t follow it,” he says. “It didn’t make sense to me.” But he persevered and came to the conclusion that “great novels [like Mrs. Dalloway} aren’t necessarily trying to tell their readers anything specific, and that if these novels mean to improve readers, they do so by imparting an expanded sense of the world.”

Mrs. Dalloway might do much the same for you as it did for Cunningham. You might like it as much as he has or as much as Jorge Luis Borges, W. H. Auden and the prodigious English novelist, Margaret Drabble, who wrote, “Virginia Woolf is one of the few writers who changed life for all of us.” Drabble added, “Her combination of intellectual courage and painful emotional sensitivity created a new way of perceiving and living in the world.” Mrs. Dalloway inhabits the same literary territory as George Eliot’s Dorothea Brooke in Middlemarch, and Joyce’s Molly Bloom in Ulysses. She’s an original immortal.

The post Mrs. Dalloway at 100: Virginia Woolf’s Modernist Masterpiece of Imperial Decline appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.