From Kerry’s Smug Dairy lineup to a new Dutch-Danish range of ‘hybrid milks’, could blending cow’s milk with plant-based ingredients be a winning solution?

At Amsterdam’s World of Private Label International Trade Show this week, two companies joined forces to showcase a new range of milk that promises to be more sustainable, without compromising on the flavour of dairy.

Dutch firm Farm Dairy and Denmark’s PlanetDairy introduced a three-strong lineup of ‘hybrid milks’, combining cow’s milk with plant proteins to deliver a 20-30% reduction in emissions.

“Consumers are willing to prioritize sustainable food options, but they refuse to compromise on taste, nutrition, or price,” argued Jakob Skovgaard, co-founder and CEO of PlanetDairy, which entered the category last year through its Audu brand of blended cheese (which combines dairy with coconut oil, potato starch, and pea protein).

“We are targeting dairy lovers who are mindful about the environmental impact of traditional dairy,” Skovgaard added.

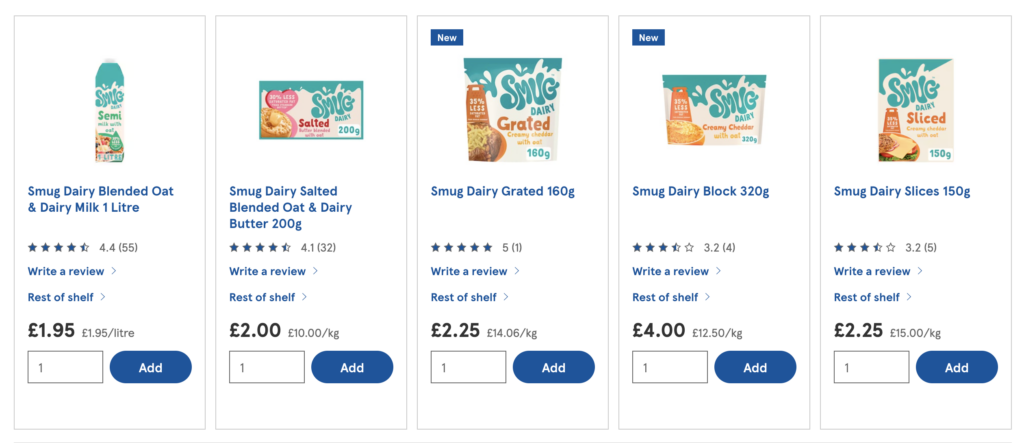

It is one of several efforts looking to blend dairy with plant-based ingredients to offer sustainability wins, with Kerry’s Smug Dairy range (combining milk with oats) perhaps the largest-scale example last year. This has dovetailed with the rise in blended meat, which omnivores have come to love and offer significant climate advantages over 100% meat.

Can hybrid dairy match the momentum, both in terms of consumer preference and planetary impact, of blended meat?

Why are brands revving up hybrid dairy?

Hybrid milks are by no means a new solution. Companies in Thailand, for example, have been selling soy milk with small amounts of dairy for years. Danish dairy giant Arla used to sell a dairy-oat milk hybrid at one point, while France’s Triballat Noyal retailed a Pâquerette & Compagnie line with 50% cow’s milk and 50% oats, almonds and hazelnuts. Live Real Milk also introduced 50-50 blends with oats or almonds. All of these have since been discontinued.

The rationale behind these products is threefold and interconnected. Consumers want an all-round nutritional profile with less saturated fat, and they’re concerned about the climate impact of dairy production; at the same time, they don’t universally love the taste of plant-based milk.

Blends seek to meet them halfway. “We expect that this range will become the standard for the ‘flexitarian’ group of consumers,” Arend Bouwer, managing director of Farm Dairy, said of the new hybrid milk offerings.

At the heart of the argument is that plant-based milk remains under-adopted. In the US, for example, only 40% of households purchased these alternatives last year, a four-point decrease from 2023. This trend is true elsewhere, too, with household penetration rates reaching 37% and 35% in Germany and the UK, respectively, Europe’s largest markets for vegan food.

Last year, a poll found that health ill effects were driving Americans to eat fewer animal products like meat and dairy, and many cut back on their purchases of plant-based alternatives because of taste (32%) and price (28%) concerns.

A recent global survey, meanwhile, suggested that among the 38% of people who don’t buy non-dairy products, 58% showcase the potential to switch if certain needs are met. The biggest problem was unsatisfactory taste or texture, which left 57% of consumers resistant to these products, followed by limited availability (55%) and high prices (37%).

At the same time, dairy is resurgent in markets like the UK and the US, with concerns around ultra-processing and nutrition playing a role too. How do consumers feel about hybrid dairy, though?

According to surveys by Mintel in 2022 and 2023, 42% of French consumers found the concept appealing, 56% of Irish respondents said they’d try hybrid cheese, and 26% of Thai citizens expressed interest in hybrid yoghurt.

Replicating blended meat ratios is crucial to hybrid dairy’s success

Would hybrid dairy as a concept work the same way as blended meat? The latter products have leveraged either plant proteins, vegetables and/or mushrooms to lower the content of beef and chicken in burgers and nuggets, respectively, with some brands outperforming 100% meat in the eyes of omnivores and flexitarians.

It’s an important lever of the protein transition. Almost all (96%) households that bought plant-based meat and seafood in 2024 also purchased conventional versions, putting flexitarians at the heart of the consumer base. Meanwhile, research shows that even replacing half of your meat consumption can reduce emissions by 31% and water use by 12%, while doubling climate benefits.

The key to these products’ winning mantra – both among consumers and for companies – is the meat-to-plant ratio and the pricing. Can hybrid dairy replicate those features while retaining the flavour?

Danone has found success here. Its Dairy & Plants Blend was described as an industry-first baby formula and, crucially, contains 60% plant protein. This indicates the importance of having a higher share of plants, which can offer better health outcomes.

All of this may turn out better for the future of the planet. Kerry’s Smug Dairy range largely focuses on dairy – its blended milk only contains 25% of plant-based ingredients, rising to 30% for its Cheddar and 25% for the block butter. The only offering with an equivalent amount of plants is its spreadable butter, which happens to be the range’s most climate-friendly product, offering 54% lower emissions than its conventional counterpart.

Dairy accounts for around 4% of global emissions, twice as high as the aviation industry. So minor cuts – like the 18% reduction achieved by the Smug Dairy milk – won’t do much to really move the needle.

Hybrid dairy isn’t more economical yet

There’s another major barrier for hybrid dairy products: the price tag. The Smug Dairy butter retails for £9.38 per kg, higher than the £7 its Kerrymaid dairy spread costs in the UK. What’s even more striking is the cost difference with plant-based counterparts (which are often knocked for their high prices). The hybrid butter is more than twice as expensive as the dairy-free spreadable butter sold by Kerry’s Pure brand (for £4.30 per kg).

There isn’t much difference between Smug Dairy’s other products and their 100% vegan counterparts. Its hybrid Cheddar block is only 36p cheaper per kg than Cathedral City’s dairy-free version, and its oat-dairy milk costs only 5p less than Alpro’s oat milk (and 15p less than its barista milk).

For price-conscious consumers, this is hardly a win. So for hybrid dairy to succeed, undercutting the price significantly from fully plant-based products is the only way to justify the currently high ratios of dairy-to-plants.

Farm Dairy and PlanetDairy know this and are targeting price parity for their new range. “By offering a retail price and taste comparable to traditional dairy, we believe we can reach a wider consumer base,” said Skovgaard.

Product formats are important too. A recent poll found that consumers are most receptive to hybrid yoghurts and ice creams, and least interested in beverages and milk alternatives. Moreover, they prefer coconuts and cashews more than other plant-based ingredients for these applications, which are yet to make their way into brand portfolios.

Will consumers take to hybrid dairy the way they have blended meat? Only if it delivers more substantial benefits than it currently does – on their wallet, on the planet, and on their own health.

The post The Rise of Hybrid Dairy: Can It Follow in Blended Meat’s Footsteps? appeared first on Green Queen.

This post was originally published on Green Queen.