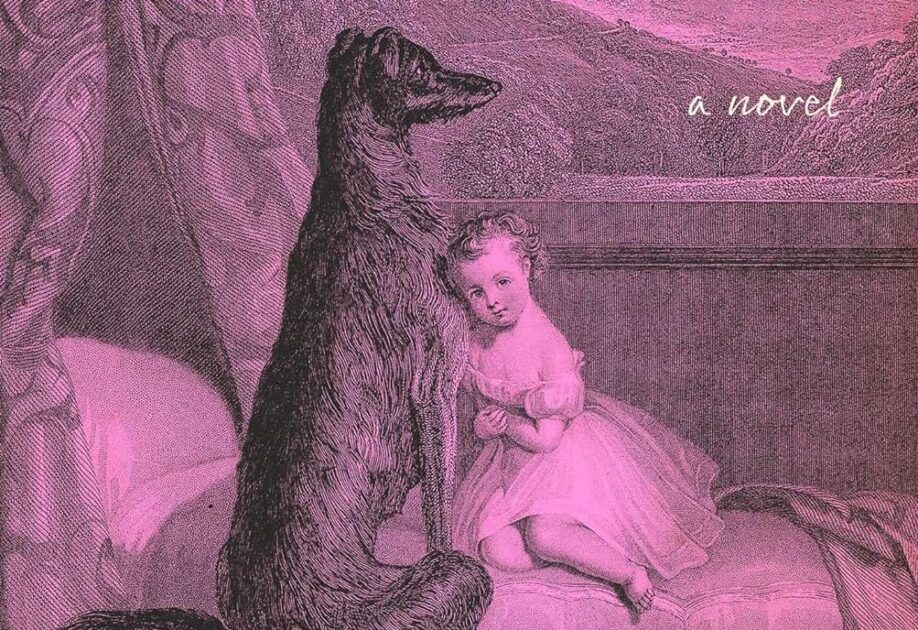

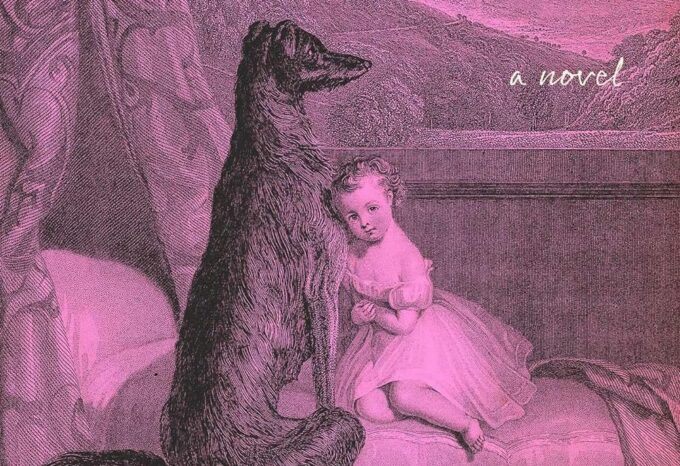

Cover art for the book Vivienne by Emmalea Russo

Emmalea Russo is a writer and astrologer. Her books of poetry are G, Wave Archive, Confetti, and Magenta. Recent work has appeared in Artforum, BOMB, Spike Art Magazine, and Los Angeles Review of Books.

We spoke a while back by Zoom about art, cancel culture, and her new novel, Vivienne. Below is the edited transcript.

John Hawkins: Emmalea, your novel Vivienne opens with a torrent of tweets and online vitriol—a cacophony that feels both surreal and painfully familiar. What was your intention with this visceral introduction?

Emmalea Russo: I wanted to drop readers directly into the storm—that overwhelming, disorienting space where online discourse lives. The opening mimics how information hits us now: fragmented, reactive, often cruel. Before you even meet Vivienne, you experience how the world sees her—through this distorted lens of hot takes and half-truths. It’s important that the reader feels that assault first, because that’s the environment Vivienne has to navigate when her past resurfaces.

Hawkins: The contrast between that digital chaos and Vivienne’s quiet, secluded life is striking. She’s an 82-year-old artist living in rural Pennsylvania, suddenly dragged back into the spotlight.

Russo: Yes, Vivienne represents a kind of artistic purity—someone who walked away from the art world decades ago to live on her own terms. But the internet doesn’t allow for that kind of retreat anymore. Her story explores what happens when a private life becomes public property, when art is judged not as itself but through the murky lens of rumor and moral panic.

Hawkins: This feels deeply connected to your own experience with Magenta, your poetry collection that was dropped by a publisher over your associations. Can you talk about that?

Russo: [Laughs darkly] It was surreal. The publisher had already listed the book on their site when they emailed demanding I explain my “affiliation” with Compact Magazine, where I’d published a few pieces. They called it a “crisis” and said my associations “put them in a very bad position.” There was no discussion about the actual content of my work—just this panic about contamination by proximity.

What shocked me wasn’t just the cancellation, but the language they used: “harm,” “safety,” “accountability.” These terms were weaponized to avoid engaging with ideas. I realized how much this puritanical mindset had infiltrated publishing—this fear that readers are so fragile, they might be “harmed” by a poem written by someone who once talked to the wrong person.

Hawkins: You wrote a brilliant essay about this called “Purity Policing is Poisoning Poetry.”

Russo: Yes, because this isn’t just about me—it’s about what happens to art when we prioritize ideological hygiene over creative risk. The essay quotes Nietzsche: “One must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star.” But right now, institutions want artists who are pre-sanitized, who won’t disrupt the narrative.

Hawkins: Vivienne’s art in the novel gets labeled “violent” and “problematic.” There’s a chilling scene where a gallery slaps a content warning on images of her work.

Russo: That comes directly from observing how we now engage with art from the past. There’s this impulse to judge historical works by contemporary moral standards, as if art should be as frictionless as a corporate mission statement. But real art should unsettle, should resist easy categorization. Vivienne’s work is challenging, ambiguous—exactly the qualities that make it dangerous in this climate.

Hawkins: Your prose mirrors this tension—lyrical and poetic but fractured by those bursts of internet-speak. Even the fonts shift between narrative and online comments.

Russo: The design was crucial. The tweets and comments appear in a stark, modern font—the visual equivalent of a screen’s glare—while Vivienne’s world is rendered in warmer, traditional type. I wanted the reader to physically feel the jarring shifts between these realities. Because that’s how we live now: one foot in the quiet of our inner lives, one foot in the screaming void of the feed.

Hawkins: Beyond the satire, there’s real grief in how Vivienne’s legacy gets rewritten by people who never knew her.

Russo: Absolutely. The book asks: Who gets to control an artist’s story? Vivienne’s actual life—her loves, her regrets, the nuanced reasons she left the art world—becomes irrelevant. She’s reduced to a hashtag, a debate topic. There’s a tragedy in that flattening, but also a perverse comedy. Some of my favorite moments in the book are when the online mob accidentally stumbles into profound truths while trying to “cancel” her.

Hawkins: You mentioned mysticism earlier—Vivienne’s story has almost a saint’s martyrdom arc. And you weave in astrology, tarot…

Russo: I’m fascinated by systems of meaning that embrace contradiction. Astrology, for me, isn’t about prediction but about metaphor—a way to talk about time and fate that linear logic can’t capture. Vivienne’s granddaughter in the novel uses tarot not to tell the future but to ask better questions. These traditions acknowledge mystery, whereas our current discourse demands absolute certainty.

Hawkins: Even your poetry—like in Magenta—feels alchemical, like you’re conjuring meaning through juxtaposition.

Russo: That’s exactly it! A poem can hold two opposing truths at once without resolving them. My work often lives in that uncomfortable space between sense and nonsense. The internet hates ambiguity—it wants everything to be either “problematic” or “valid.” But art thrives in the gray zones.

Hawkins: Speaking of the internet, the comment sections in Vivienne are horrifying yet weirdly poetic.

Russo: [Laughs] Thank you! I studied the rhythms of online discourse—how outrage follows predictable patterns, how sincerity curdles into performance. Those sections are like found poetry. The scariest part was realizing how easy it was to channel that voice. We’ve all internalized the syntax of viral condemnation.

Hawkins: The novel’s climax takes this to an almost mythic level—without spoilers, Vivienne’s fate seems to literalize what cancel culture does metaphorically.

Russo: Yes, the ending asks: What happens when society’s need to purge its “monsters” collides with an artist’s refusal to apologize? There’s a dark humor there—the absurdity of demanding accountability from an 82-year-old recluse. But also real pathos, because Vivienne does grapple with guilt, just not in the way the mob wants.

Hawkins: After your experiences, do you see hope for art outside this purity paradigm?

Russo: Absolutely. The backlash is already happening—readers are hungry for work that risks complexity. My hope is that we’re nearing the end of this moral panic, that we’ll remember art isn’t activism or therapy but something wilder. As Vivienne says at one point: “A painting isn’t a policy proposal.”

Hawkins: Let’s end with a reading—maybe one of the internet sections to show that bizarre poetry?

Russo: [Reads excerpt]

@CancelGurl69: Vivienne dahl is LITERALLY a murderer prove me wrong

@MarxBro420: her “art” is just rich lady blood magic

@AstroCyborg: actually her mercury was in retrograde when she—

@CancelGurl69: STFU astro freaks this isn’t about ~vibes~ it’s about JUSTICE

See how it veers from faux-academic to unhinged? That’s the chorus Vivienne’s up against.

Hawkins: Perfect. Last question: If Vivienne could tweet one thing to her detractors, what would it be?

Russo: [Pauses] Probably just: “No.” [Laughs] The ultimate refusal to play the game.

Hawkins: Emmalea Russo, everyone. Vivienne is out now.

#####

Russo reads an excerpt from Vivienne: https://sonix.ai/clips/qzoFkVEw7aWHiQFMU77T4dpD

Russo’s essay, “Purity-Policing Is Poison to Poetry” is here.

The post The Chaos of Creation: An Interview with Emmalea Russo appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.