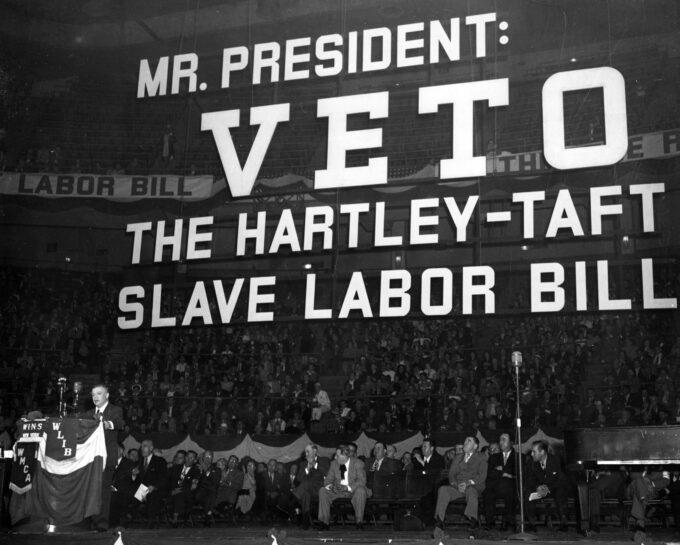

David Dubinsky of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union speaks against the Taft–Hartley Act, May 4, 1947

If you’ve ever watched a union campaign get crushed by employer intimidation, wondered why you see so few strikes, or been frustrated that unions don’t demand more on climate or racial justice, you’re seeing the effects of a US law passed 78 years ago today.

On June 23, 1947, the United States Congress overrode a presidential veto to enact the Labor Management Relations Act, better known as the Taft-Hartley Act. Pushed through by a coalition of conservative Southern Democrats and Republicans during a wave of postwar strikes and growing public support for unions, the law gave employers new legal weapons and undercut some of organized labor’s most powerful tactics. Nearly eight decades later, most of its provisions are still in place.

Taft-Hartley marked the beginning of a long-term strategy to isolate, weaken, and demobilize organized labor in the United States. It sought to narrow the scope of what unions do by restricting what they bargain over, limiting their political activity, and constraining the tactics they can legally use. This helped shape public perception of unions as narrow, service-oriented entities rather than vehicles for broader economic and social change — a legacy that haunts the US labor movement to this day. As workers across the country seek to rebuild their collective power, it’s worth taking a look at the legal behemoth making their mission harder to achieve.

So, without further ado, here are six ways that Taft-Hartley rigged the system against workers.

1. Gave Employers the Power to Interfere in Union Elections

Prior to Taft-Hartley, employers’ legal ability to interfere in union organizing drives and elections was relatively circumscribed by the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935. The idea was that workers, and only workers, should be allowed to decide whether they wanted to be part of a union; it’s not the employer’s decision to make, so there’s no reason they should have a say in the matter. Taft-Hartley, however, substantially loosened these restrictions, ostensibly to protect the employer’s right to “free speech.” So long as they avoided explicit threats or promises of benefits, employers were now free to fully exploit their inherent power advantage to sabotage union organizing drives. It was this provision that brought us the captive audience meeting, in which workers are required to sit through hours of their employer’s anti-union propaganda. Many of the surveillance and intimidation tactics that are so common today got their start in 1947 with this section of the Taft-Hartley Act. The provision did create jobs, though — jobs for anti-union lawyers and consultants.

2. Banned Solidarity Strikes and Boycotts

Before the Taft-Hartley Act, US workers could engage in secondary or “solidarity” strikes, where workers from one company would strike or picket to support workers at another company. Unions could refuse to handle goods from a struck employer. These actions gave workers at different workplaces significantly more power and leverage in negotiating with their employers, enabling workers across a supply chain to join forces and exert pressure. Solidarity actions particularly benefited workers in industries where a strike would be less disruptive for the economy as a whole. They also reinforced the idea of a labor movement that encompassed the entire working class, rather than one that was siloed by workplace or industry.

Taft-Hartley changed this by explicitly forbidding solidarity strikes. In doing so, it fractured cross-union support and isolated labor struggles within individual employers. It also weakened the workers’ negotiating power and helped chip away at the burgeoning class consciousness that had powered solidarity actions. While other countries with more powerful labor movements continue to utilize solidarity actions to great effect, the power of organized labor in the US has continued to decline.

3. Undermined Unions Financially and Paved the Way for ‘Right-to-Work’ Laws

Prior to Taft-Hartley, closed union shops were fairly common. Workers in a union shop benefited from the efforts of those who negotiated and enforced their contract, and all were expected to share in covering the costs of that collective work. This kept unions well-funded and unified, eliminating potential free-rider problems where workers benefit from union representation without contributing to its costs. The Taft-Hartley Act changed this by banning union security agreements — agreements between unions and employers that require workers who are covered by a union contract to join the union. Union contracts, however, were still legally required to cover everyone eligible to join the union, regardless of whether those workers chose to join the union officially as members. The Taft-Hartley provision created a potential unfunded mandate for unions by requiring them to represent all workers covered by the contract, including those who refused to join or pay dues. It also paved the way for so-called right-to-work laws, which ban unions from recouping the cost of representing non-members in the form of non-member agency fees. Nearly half of US states now have such laws, which send a clear anti-labor message despite their “right to work” moniker.

4. Allowed Employers to Push for Union Decertification During Strikes

The Taft-Hartley Act took aim at what is arguably workers’ most significant weapon: the ability to withhold their labor. Before 1947, the law viewed decertification votes — effectively votes to disband the union — during ongoing labor disputes with great skepticism, generally interpreting them as a form of employer coercion or retaliation. Section 9(c)(1)(B) of the Taft-Hartley Act, however, allowed employers to petition for a decertification vote during a strike by arguing that the union had lost majority support. Employers could hire scabs to replace striking workers and then call for a decertification vote, which would drain union resources even if the union ultimately prevailed in the election. Allowing employers to file such petitions in the first place also reinforced the employer’s unwarranted role in union decision-making. In practical terms, the new law meant employers could exploit a strike to destroy a union. The specter of union decertification also served to dissuade union workers from striking in the first place, significantly eroding their leverage at the bargaining table and beyond.

5. Required Union Members to Sign Anti-Communist Affidavits

In the mid-20th century, many of the most successful union organizers were proud leftists. Wary of growing class-consciousness, however, the authors of the Taft-Hartley Act inserted a political litmus test for union officers, requiring them to swear that they weren’t communists. Those who refused could not access the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), rendering them unable to file unfair labor practice charges, hold union elections, or petition for recognition. Although this particular provision was later repealed, it still caused significant damage. The Congress of Industrial Organizations — the CIO in the AFL-CIO — expelled a dozen unions that refused to comply with the new edict, purging many of the labor movement’s most effective and militant leaders. The expulsions created long-lasting rifts in the working class, especially among Black, immigrant, and left-wing workers who had been central to earlier organizing drives. The affidavit requirement was also part of a broader anti-communist crackdown that encouraged exactly the kind of anti-worker surveillance that has become common today.

6. Limited the Scope of Union Work

When the Taft-Hartley Act was passed, courts were still determining the boundaries of the topics covered by the NLRA’s requirement that employers bargain in good faith. Many unions pursued broad workplace demands, touching on everything from hiring practices to community environmental issues. Class-conscious unions were also empowered to spend members’ dues on political advocacy and campaigns. Taft-Hartley sought to significantly narrow the scope of union work, however, by restricting mandatory subjects of bargaining and banning the use of membership dues for direct political contributions. Employers were required only to negotiate over “wages, hours, and other terms and conditions of employment,” and unions needed to solicit additional member contributions for anything besides direct representational work. Together, these provisions shrunk the role of unions in shaping the workplace and their power in society as a whole. This means that unions aren’t directly involved in fighting for environmental justice, even as their employers’ pollution poisons the homes of their families. It also helped usher in “business unionism,” which avoided class struggle in favor of a narrow focus on wages and contracts. Business unionism treated union membership more like a dues-for-service insurance policy than a means to structural change.

Today is the anniversary of a strategic legal assault on worker solidarity and class struggle. Most of its provisions are still in effect today, and the one on this list that isn’t nevertheless did lasting damage. It is worth remembering, however, that workers weren’t benevolently handed the 1935 version of the NLRA. The pro-worker protections of the NLRA were a response to militant labor uprisings and mass pressure, a victory for those who advocated for a fairer system in the face of often violent repression. While Taft-Hartley rolled back many of those gains, the fact that the US had them in the first place (and that workers in other countries still enjoy such protections) shows that a more pro-worker system is both possible and winnable. This isn’t to say it won’t be an uphill battle on an uneven playing field; the law has long reflected the interests of capital more than those of working people, and those in power didn’t get that way by making the system easy to change. But if labor rights were won through struggle once, they can be won again — if workers are willing to fight for them.

This first appeared on CERP.

The post Six Ways a 78-Year-Old Law is Still Screwing Workers appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.