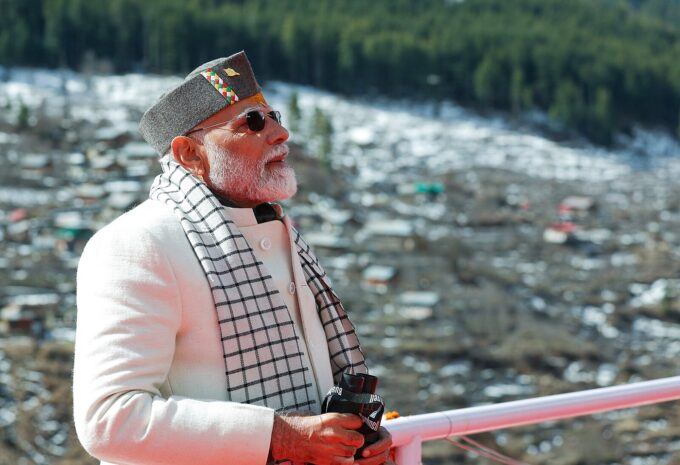

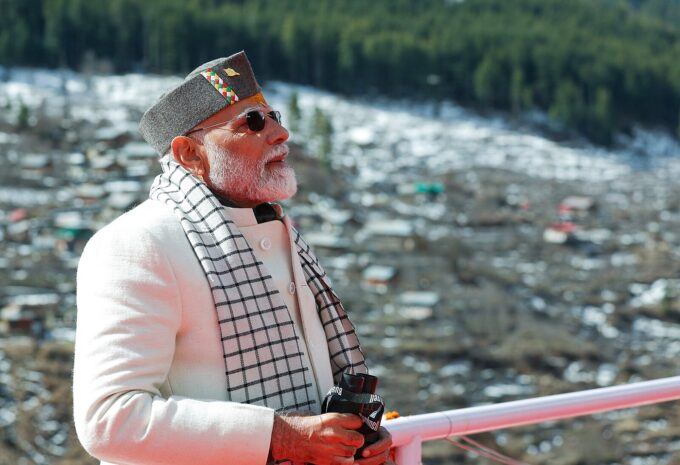

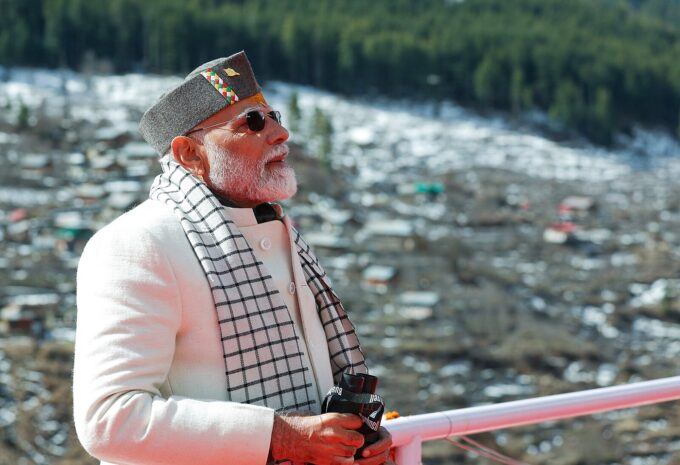

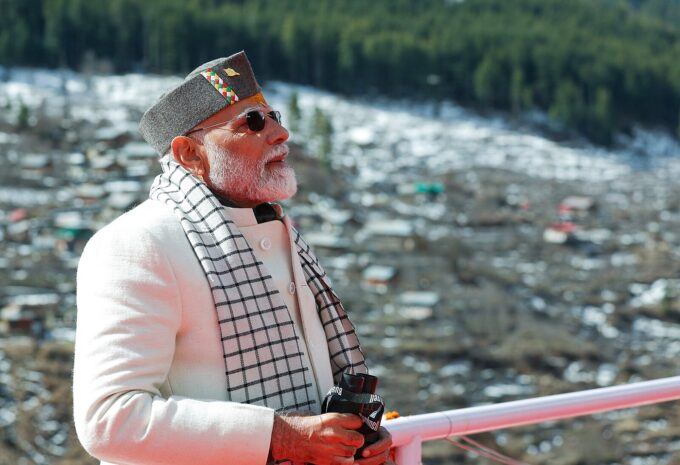

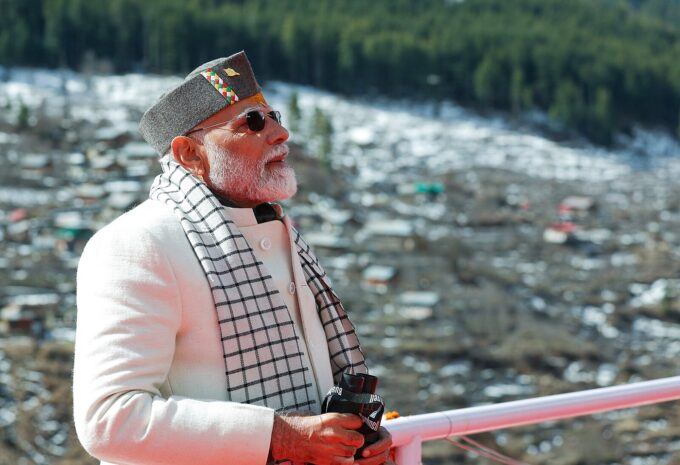

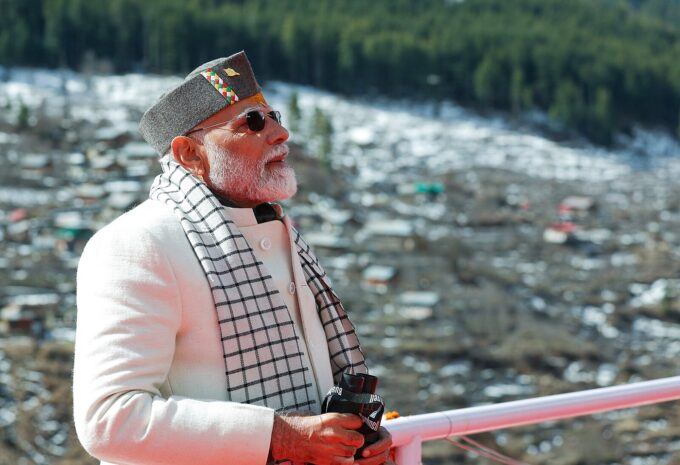

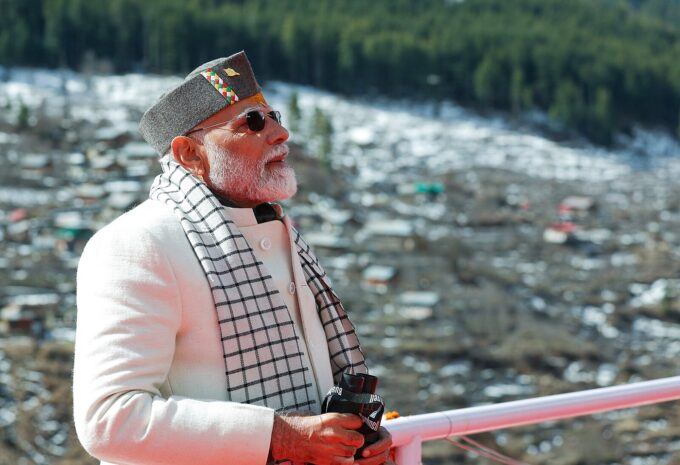

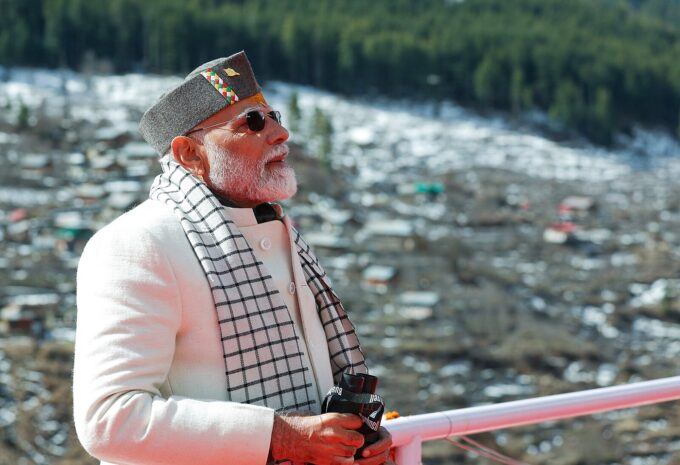

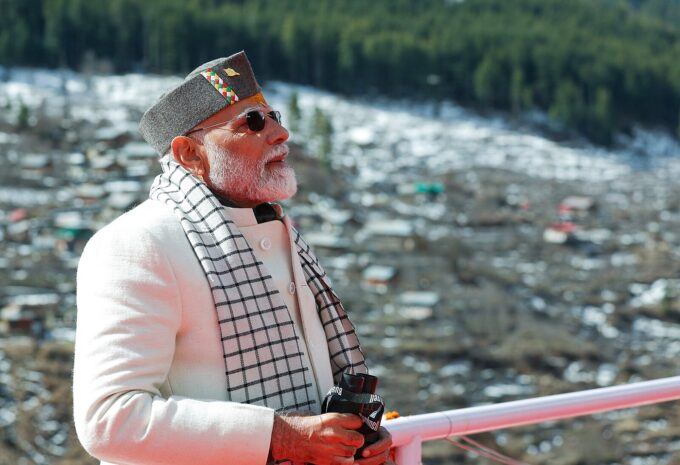

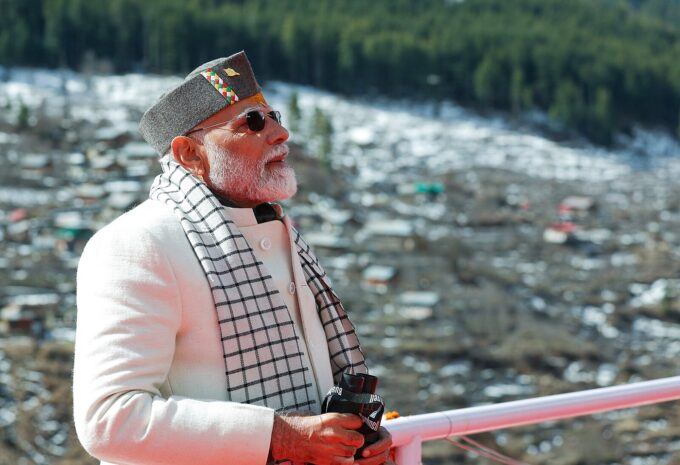

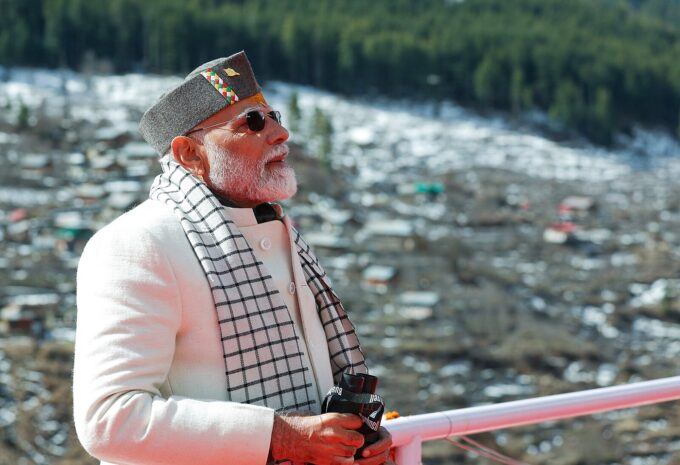

Photograph Source: Prime Minister’s Office – GODL-India

A strong economy is essential for becoming a superpower, a proven historical formula. India is projected to be the world’s second-largest economy by 2050, surpassing the U.S. However, obstacles remain. No region or country is actively supporting India’s efforts to overtake the U.S. as a global power. Even China would prefer a distant hegemon over a nearby one. Pakistan and even some Western nations oppose India becoming a superpower, a move that would give India a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council, which India would rightfully demand and deserve, perhaps replacing the United Kingdom or France.

This commentary argues that the U.S. and India’s neighbors may actively hinder India’s rise as a superpower. The competitors and rivals have numerous options, including imposing tariffs and trade barriers, reducing the exports of Indian goods and services, withholding essential exports to India, and curtailing remittances from Indian workers. Suppose India continues to advance despite obstacles. In that case, some rivals might even encourage separatist movements in Khalistan, Kashmir, and the Northeastern states (Assam, Nagaland, and others), which have tenuous geographical, ethnic, and cultural ties to the mainland.

This analysis does not suggest a global conspiracy or active collusion against India. Instead, it highlights possible strategic moves within the contested space that India’s competitors and rivals recognize but do not openly voice, which is the most effective form of complicity. Though the comparison is somewhat unreal, just as the fall of the Soviet Union diminished Russia’s global influence and economic weight, strategies targeting India’s economy and territorial cohesion involve similarly high stakes. This article does not address whether India will succeed in overcoming resistance to become the second-largest global economy.

Western Perspectives

Geopolitical arguments that are valid in one era might not hold true in another. Consider three reasons why the Western perspectives on India’s rise as an economic superpower are no longer supported. Losing the active backing of Western allies would be a significant setback for India.

First, free trade faces growing pressure. In theory, nations buy and sell without tariffs or quotas. The World Trade Organization (WTO) rests on principles that promote open trade. Yet, India and other countries often seek to export more than they import to shield domestic industries. This protectionism, clashing with WTO ideals, is also expanding in the West and could cause substantial harm to India.

Second, Western policymakers once supported India’s trade privileges by pointing to its democratic credentials. That logic is losing relevance. In today’s competitive landscape, democracy does not entitle a country to concessions that undermine U.S. or European economies, just as autocracy no longer disqualifies trade partners when mutual interests align. The form of government is no longer decisive; what matters is the economic advantage.

Third, for decades, Western strategy rested on strengthening India as a counterweight to contain China. That policy is under review. India itself shows little willingness or capacity to shoulder that burden. Supporting India risks creating a rival that might outpace the U.S. If both China and India rise to occupy the top two spots in global economies, the U.S. would fall to third, with Western Europe even further behind. At that point, the world’s economic center of gravity would shift decisively eastward. Resisting India from overtaking the U.S. makes far more sense strategically than clinging to the illusion that India can restrain China, an unstoppable economic superpower. However, this clarity has not yet moved beyond doubt.

India By 2050

The idea that India will surpass the U. S. in its share of global gross domestic product (GDP) by 2050 has attracted a lot of attention in long-term economic forecasts. GDP is the total monetary value of all goods and services produced within a country for one year. Global GDP is the sum of all individual countries’ GDPs. In 2025, the U.S. accounts for about 25% of the world’s GDP, while India makes up roughly 4%. China is close to 18%. For now, India is far behind China and the U.S.

The likelihood of India surpassing the U.S. is drawn on projections from reputable institutions such as PwC and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Analysts emphasize the difference between nominal GDP, measured in current U.S. dollars, and purchasing power parity (PPP), which adjusts for cost-of-living differences and often provides a more accurate measure of economic strength in emerging markets. On a PPP basis, India has a realistic chance, estimated at 70–80%, of surpassing the U.S. by 2050 to become the world’s second-largest economy after China.

These projections assume annual growth rates of 5–6%, supported by India’s large working-age population, expanding digital infrastructure, and ongoing reforms. If growth rates remain steady, India’s economy could reach $15–25 trillion by mid-century. Meanwhile, slower U.S. growth of 1–2% annually might allow India to close the gap more quickly. Nevertheless, these scenarios heavily depend on India’s ability to sustain reforms and address structural challenges.

India’s Oil Trade

India’s top five exports include refined petroleum ($55-79 billion), generic pharmaceuticals ($21 billion), diamonds ($20 billion), telephones ($19 billion), and jewelry ($12 billion). India maintains a trade surplus with 151 countries worldwide, including the U.S., showing it has successfully developed foreign markets to sell more products than it imports, resulting in a surplus.

India runs trade deficits with Russia, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, all major oil producers. Because domestic crude production is insufficient, India imports heavily to meet its internal energy demand. Yet India has converted this weakness into its top export. It buys crude oil, refines it into petrol, diesel, and jet fuel, and then exports these, forming the largest share of its trade surplus. India now operates some of the world’s largest oil refineries.

The U.S. has increasingly criticized India’s trade in refined petroleum derived from Russian crude, framing it as indirect support for Russia’s economy amid the Ukraine conflict. This scrutiny has intensified with targeted measures, such as U.S. tariffs on Indian refined petroleum exports and threats of sanctions against major refiners like Reliance Industries, which reportedly earned $5 billion from Russian oil imports in 2024. The U.S. actions aim to curb India’s oil trade surplus, which constitutes the largest source of its export revenue, thereby posing a strategic challenge to India’s economic ascent. By undermining India’s largest export sector, the U.S. seeks to slow its trajectory toward becoming the world’s second-largest economy.

U.S. Shift

In his second term (2025-29), President Trump’s sharp turn toward a confrontational stance with India has startled many observers, since earlier administrations cultivated closer ties. Yet this shift becomes more understandable in the context of economic rivalry. India openly aspires to surpass the United States in global GDP rankings, and Washington sees no advantage in facilitating that outcome. If India continues running a growing trade surplus with the U.S., the American economy gains little while risking its own relative decline.

India’s goods trade surplus with the U.S. reached above $45 billion in 2024, a 5.9 percent increase ($2.6 billion) compared to 2023. The U.S. has a small trade surplus of $100 million in services. India is thus a net gainer by a vast margin. The U.S. wants India to open its markets for American agricultural products, but India is reluctant because it doesn’t want to harm its domestic agriculture, which supports millions of people.

The U.S. is unlikely to compromise its exports in the name of free trade or democratic solidarity and allow India to benefit from its unequal views on trade reciprocity. High tariffs on Indian goods make sense not only for trade balance reasons but also strategically to slow India’s progress to the second spot. U.S. manufacturing companies are being asked to relocate from China to India, a move that does not align with the U.S. strategy to prevent India from surpassing the U.S. in global rankings.

Additionally, the U.S. has little interest in allowing Indian immigrants to send substantial amounts of money back to India, which fuels the Indian economy. “Indians . . . received nearly two-thirds of H-1B temporary visas for highly skilled workers issued in 2023.” The U.S. may reverse this policy to reduce Indian remittances. Sending illegal Indian immigrants back to India on U.S. Air Force aircraft reflects President Trump’s views on illegal immigration. It takes on a different meaning when considered in the context of slowing cooperation with India.

Evidence now shows that the U.S. has decided not to treat India as a counterbalance to China. If India succeeds in surpassing the U.S., it may shift policy and team up with China to weaken U.S. influence regionally and globally. President Trump will not attend the Quad meeting in India, an alliance of the U.S., India, Australia, and Japan. The Quad is meant to contain China. But if the goal is to stop India, the Quad does not make sense. A massive demonstration against Indian immigrants in Australia is also an early signal of the Quad’s diminishing value. India-sponsored assassinations in Canada and the U.S. have also been identified and condemned.

A pattern of facts and policies is emerging, indicating that the U.S. is trying to build multiple barriers to prevent India from becoming the world’s second-largest economy before the U.S.

The shifting tone of U.S. foreign policy is evident. Trump invited Pakistan’s Army Chief to lunch at the White House after a brief India-Pakistan short war (May 7-10, involving Operation Sindoor by India and retaliatory strikes by Pakistan). Trump even insinuated that India lost several planes during the military clash with Pakistan. Sensing a deterioration in U.S.-India relations, Pakistan nominated Trump for the Nobel Peace Prize for halting the war. Courting Pakistan, the prime rival of India, is more than cosmetics or a tactic to wring trade benefits from India. This move seems like a strategic hedge against India’s ascent.

Regional Rivalry

India, once seen as South Asia’s natural leader, is gradually losing influence to China, whose economic investments and strategic alliances are reshaping regional dynamics. China’s rapid rise as a global economic and military power has given regional countries more options between India and China. China now appears to surpass India in establishing relationships that were supposed to be under New Delhi’s control. Countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal—neighbors India long thought fell within its sphere of influence—are increasingly leaning toward Beijing. China’s investment policy often leads to debt traps. Still, nations accept it for short-term gains. Meanwhile, India’s method of using economic sanctions to change other countries’ behaviors is seen as disrespectful.

The territorial disputes with both Pakistan and China have only intensified the geostrategic shift. The ongoing conflict over Kashmir strengthens the China–Pakistan alliance, creating a two-front challenge for India. Even more distant countries, such as Iran and Afghanistan, are being drawn into China’s growing sphere. In any future war with Pakistan, India would most likely face both Pakistan and China.

Meanwhile, the collapse of the pro-India Hasina Wajid government in Bangladesh has created fresh openings for China and Pakistan to exert pressure along India’s vulnerable eastern flank. Analysts warn that such developments, if unchecked, could even stir separatist currents among India’s nine northeastern states, where loyalty to the center has historically been fragile.

OIC Concerns

Among India’s adversaries, Pakistan remains the most persistent and troubling, with influence that extends well beyond South Asia due to its key role in the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), a group of fifty-seven Muslim-majority countries. During armed conflicts with India, Pakistan consistently gains moral, diplomatic, and sometimes even military support from some OIC members, though most Arab states remain neutral. Arab states, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have increasingly prioritized economic pragmatism, blocking stronger anti-India language in OIC forums.

Yet, India lacks a comparable group of states to rely on. Instead, its close relationship with Israel, which is strategic, alienates many Muslim nations that strongly support the Palestinian cause. This allows Pakistan to position itself not only as India’s regional rival but also as a religiously connected partner within a broader Muslim world.

However, the OIC is not only a political challenge for India; it is also a vital economic arena, though it does not function as a unified bloc like the European Union. Millions of Indian workers in Gulf states remit billions of dollars yearly, and trade with Muslim countries generates substantial revenue. India enjoys surpluses with several OIC economies, making these markets critical for growth. Gulf states regard India as both a promising investment destination and a trading partner.

India’s economic ties with OIC nations remain fragile due to two critical factors. First, the rise of Hindutva politics and policies perceived as targeting India’s Muslim minority, such as the 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act, which excludes certain Muslim groups, and the revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s autonomy, have sparked condemnation in Muslim-majority capitals like Ankara and Kuala Lumpur. In 2020, the OIC issued a resolution criticizing India’s Kashmir policies, straining diplomatic relations.

The economic dimension exacerbates these tensions. Nearly eight million Indian workers in the Gulf remit about $50 billion annually, and India maintains a $60 billion trade surplus with OIC economies. If discontent over Kashmir or Hindutva politics deepens, Gulf governments could reconsider trade preferences or investment flows, undermining one of India’s most vital external revenue streams. Thus, religious and political disputes risk spilling directly into the economic sphere, exposing a vulnerability that could slow India’s global ascent.

Second, the ongoing rivalry with Pakistan means that the OIC states, despite their strong financial ties with India, cannot abandon Islamabad during armed conflicts. For them, Pakistan, despite its weak economy, remains a brotherly nation, connected by history, religion, and shared security concerns. Iran’s support for Pakistan in the May 2025 military conflict with India, disguised as mediation, surprised Indian foreign policy analysts. Turkey and Azerbaijan were even more open in siding with Pakistan, even though these countries have significant economic interests in India.

India finds itself caught in a complex paradox. Muslim nations value India as an economic partner and investment hub. Yet, India is mistrusted in a region where religious solidarity and historical grievances remain powerful forces. India’s rise as a global power will depend not only on countering China’s growing regional influence but also on managing the delicate currents of identity, religion, and rivalry that continue to shape South Asia. A foreign policy that relies heavily on coercion against smaller neighbors risks undermining the stability and goodwill that India needs for long-term economic and geopolitical success.

Conclusion

India is rapidly advancing to become the world’s second-largest economy by 2050. Once this milestone is reached, India will seek a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, a position it deserves. The U.S. and other Western countries might see limited strategic advantage in this change. If China and India become the top two economies, the U.S. risks losing its long-standing economic dominance. This could accelerate the shift of geopolitical power toward Asia, challenging Western influence; however, India’s rivalry with China may complicate such a realignment.

Driven by strategic interests, the U.S. seems to be creating barriers to slow India’s emergence as a leading economy. Tariffs, criticism of India’s oil exports, H-1B visa restrictions, and closer US-Pakistan ties indicate reluctance to support India’s superpower ambitions. Caught between China and India, the U.S. policy of viewing India as an economic rival remains unclear.

The growth of Hindutva politics risks alienating OIC countries by increasing tensions over India’s Muslim minority and Kashmir policies, potentially harming economic relationships with Gulf nations. Although unlikely, prolonged unrest in Punjab, Kashmir, or the Northeast could weaken India’s unity. In the worst-case scenario, as rivals might imagine, India could face foreign-engineered secessions, which would significantly diminish its economic and political influence. Viewing these obstacles, India needs to review its regional and global policies.

The post The Obstacles to India’s Superpower Ambition appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.