We live in an age of satire – unintended self-satire. Events of profound consequence have a ridiculous quality to them that competes with our emotions of worry and dread. Trump’s America is not alone in this. Look across the Atlantic: a cosmopolitan all-star Vaudeville troupe struggling, as always, to keep up with its trans-Atlantic model and seigneur. The comedic effect is accentuated by the straightlaced mien that accompanies their most ludicrous behavior.

Satire marks other aspects of contemporary society, as well. A few years ago, we were treated to a nonpareil episode of humor when Saudi’s Prince Mohammed bin-Salman (MBS) and his pal UAE President Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (MZN) bid against each other for the supposed Leonardo masterpiece Salvator Mundi at Christie’s. Salman wanted it as a trophy; Nahyan wanted it to send Salman as birthday gift. Neither knew of the other’s silent bid. It sold finally for $45O million. That’s about the same value as Qatari Emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani’s gift to Trump of a refurbished Boeing 747 Seraglio II.

At the time, these shenanigans of the art world prompted me to reflect on the peculiarities of determining aesthetic value in a celebrity setting where money and prestige rule. See below. When written, the role of the Gulf princes had not as yet been revealed. No updating seems necessary, though.

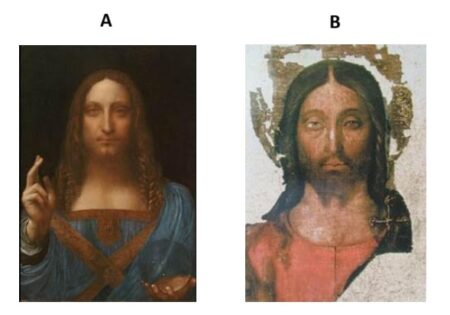

Which painting is superior?

Which painting is a better investment?

Which painting would you prefer hanging in your residence?

Most people wouldn’t hesitate to pronounce that it is the supposed Leonardo, named Salvator Mundi, that sold in 2017 for nearly half a billion dollars at Christie’s. After all, if it’s by the supreme Leonardo, it has to surpass anything done by a lesser artist. That automatically makes it a better investment since the cachet of a Leonardo, who is credited with only a dozen or so paintings, is unique. Only a Michelangelo or a Raphael could come close to reaching similar astronomical levels. So, Salvator Mundi is likely to hold its value more securely than anything else but blackmail. Even blackmail usually carries a generational expiration date.

Imagine its potential financial utility. It could serve as collateral for loans needed to mount a political campaign. Or be the centerpiece of a dowry package. Or could be sold for cash – that most fungible of assets. Great Master art has experienced a sharp rise in market value for decades now with only a few, very brief interruptions. A sale can be counted on to turn a profit. In a pinch, the owner could turn to whomever was bidding only $400 million and has been drowning his sorrows ever since.

All of this presumes, of course, that the painting’s authenticity remains beyond reasonable doubt. That is not a certainty, though. The provenance is murky, and experts debated for years as to whether this was a genuine Leonardo. The most subtle scientific tests cannot remove all margin of uncertainty when it comes to separating the real article from a skillful forgery – or, more likely, a mislabeling (intentional or not). The New York Times art critic, Jason Farago, has affirmed his judgment that Salvator Mundi is a quality work by a Lombard artist of the late Renaissance who was intimately familiar with Leonardo’s other paintings – and, perhaps, with the artist himself who resided many years in Milano at the court of the Duke of Sforza.1

We should remind ourselves that there is a long history of misattributions, and shifting judgments as to whether a particular work of art was by a Great Master. Rembrandt paintings, far more numerous, have engendered endless controversies. The most esteemed authorities have debated intensely whether a given picture was by Rembrandt himself, done in collaboration with assistants, from the workshop of Rembrandt, in the style of Rembrandt, or the product of a Dutch artist who once accidentally jostled him at the Amsterdam fish market. In the end, the only (least common denominator) consensus was that the picture was not painted in a Queens garage.

These dramatic episodes of artistic contention are puzzling to somebody outside the tight circle of cognoscenti. If a painting is so extraordinarily enchanting as to be placed on a par, or near par, with acknowledged masterpieces, what aesthetic difference does it make whether the Master himself did it. Its intrinsic artistic value resides in the work itself, to be neither enhanced nor diminished by its exact provenance. If the final verdict on a disputed painting is thumbs down, it is relegated to a dusty corner in the storeroom. Isn’t it more reasonable to celebrate the discovery of an anonymous artist whose work is on the same level as that of the great Master? But we do not live, think or feel in a pure world of aesthetic values. Prestige, status and the financial are intermingled with the aesthetic. There is the rub. Some approach the disputed work of art in a pecuniary mode, some are sensitive to associations, some are ravished by the thought that the object may actually have felt the brush or chisel in the hand of the fabled “Y.” This last approximates what the Indians call Darshan – being touched by the spiritual emanations from a great soul in whose presence you blessedly are. That is how a Jackson Pollock or a row of Campbell soup cans by Andy Warhol excites the acquisitively passionate as did a relic of the True Cross for a Medieval believer. A Leonardo portrait of Jesus is tantamount to the Cross itself – plus the crown, the cape and the dice. (Add a ‘selfie’ of a Roman Centurion and doubtless a well-paid consultant/expert will vouch for it).

Christie’s executives, along with their assembled team of experts, have not helped matters by their aloofness. One issue raised by the skeptics focused on the image as it appears in the clear orb held by “Jesus.” It is not inverted as one would expect Leonardo, whose studies of optics are well known, would have depicted it. There is no refraction at all. Christie’s response: Leonardo did that intentionally to call attention to Christ’s Divine powers which transcended earthly matters like perceptual physics. This question and answer may prudently be noted by anyone who is contemplating presenting a $750 million bid to the present owner. (By the way, Christie’s cut of the swag is $50 million).

Technical methods of analysis have largely supplanted more subjective bases for determining authenticity. In the old days, specialists who had spent a lifetime steeped in the Old Masters would fix their concentrated gaze on a questionable work and then declare that it either “looked like an “X” or did not look like an “X.” All other factors, like provenance, tended to be colored by that instinctive “feel.” A brilliant, clever forger (or mis-labeler) could exploit that practice by introducing elements that resonated with the expert appraiser. Any number of details pertaining to composition, perspective, color tones, brushstroke, etc. could be suggestive. As might theme. An especially ingenious ploy is to leave signs of previous restoration work, poorly done, so as to enhance the impact when the “original” is revealed. (Some politicians have been known to try something similar; their sterling image returned to its pristine state after cleansed of the slanders cast on it by their opponents, e.g. a declaration that “my sole visit to Epstein’s Isle in the Sun on Air Lolita was to find a serene location where I could work undisturbed on my candidacy announcement”).

The most one feature of Salvator Mundi that says “Leonardo” is the similarity between the visage of the Christ figure to other iconic faces that dominate Leonardo’s great classics. Mona Lisa, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, Leda and the Swan, and a number of drawings. They all bear a close family resemblance. They could be siblings or parents. Scholars often have commented that Leonardo appeared to be searching for, and attempting to represent the most perfect, transcendentally beautiful face. He clearly was fixated on variations of the image with which we are familiar. So, it would not be surprising that his alleged depiction of Jesus would fit the pattern. That fact in itself tells us nothing about Salvator Mundi’s authenticity. This is what one reasonably would expect Leonardo to have done. This is what an apt fellow painter might do as a bow to the master, to attract a client, to satisfy a patron – or to pass it off as a genuine Leonardo.

What of the ultimate question: which painting would we prefer to live with? The ‘B” painting is by the Renaissance artist Melozzo da Forli who did a stunning Christ portrait that hangs in the Palazza Ducale of Urbino. His Jesus has eyes that transfix you and burn like ice. Quite unlike the pasty face and puzzled look of the Salvator model. No question about its authenticity. All sorts of factors, of course, will be at play in determining an individual’s preference. Reactions are unpredictable; so long as we don’t know the name of the supposed artist of “A” and/or how much was paid for it. For it is a rare person whose perspective will not be influenced by that knowledge.

As to the mysterious winner of the auction, and present owner of Salvator Mundi, we can only speculate as to motivation and as to what will be done with the piece. We are living in one of the world’s great ages of conspicuous consumption. Understandably so. Enormous amounts of cash are sloshing around the world – unattached to any purpose other than self-aggrandizement – and largely in the pockets of louts unschooled in the arts. They are after trophies: trophy houses, trophy wives, trophy yachts (magnificent enough to lure aboard a trophy former President), and trophy arts. There are no Medicis among this set.

The impulse to “show off’ suggests that person “Z” will display it to others – whether those others be a general audience, a select group of fellow billionaires (e.g. inviting the Trump cabinet for tea), his fellow princes of the royal family, capos of Russian mafia families; his triad partners in a Chinese syndicate; or the one person he is enthralled with or wishes to enthrall. There also is the possibility that person “Z” is a billionaire isolate with a miser’s temperament. Possibly, he is satisfied with it being his exclusive possession. Perhaps, looked at only occasionally in solitude when extracted from the ultra-secure vault where it is secreted. An icon for one in the Age of Narcissism.

If the last, the ultimate irony would be the miser’s decision to hide it in a Jackson Height’s storage unit off the Long Island Expressway – awaiting an opportune moment to palm it off on Elon Musk who, in turn, is hoping that the offering would restore himself to the good graces of Donald Trump – the true Salvator Mundi.

Comment by reader:

“It does have a whiff of a racket, from one end all the way through to the other. One gathers enough ‘experts’ to intellectualise and pore over the technical artistic minutiae to be able to thread some coherent story. In this case, the orb’s inverted reflection forgone for a hollow glass bubble lacking any optical refraction owing to Christ’s miraculous quality. So, a long forgotten $10,000 16th century painting sitting in New York in 2005 is now suddenly a ‘rediscovered’ $450m Da Vinci, pull the other one. The entire attribution rests on this interpretation of the orb’s miraculous optical qualities, or lack thereof. Far too convenient. There is a total lack of alignment between the experts, restorers, dealers and auctions houses versus the buyers. The information set is either misinterpreted or skewed or not complete. It is more convenient for all to call this a Da Vinci than not, everyone wins and walks off in a glow of miraculous genius, and huge profit. Perhaps this is a lovely painting made by a young fellow in homage to the great Master, who did not have his scientific, technical or optical expertise to pick up on the orb’s refraction? As for KYC, AML and due diligence — give me a break, the bookies are akin to estate agents. They all just want to clip the $400m ticket.”

ENDNOTE:

The post Leonardo: The $450 Million Man first appeared on Dissident Voice.“I can say … what I felt I was looking at when I took my place among the crowds who’d queued an hour or more to behold and endlessly photograph Salvator Mundi: a proficient but not especially distinguished religious picture from turn-of-the-16th-century Lombardy, put through a wringer of restorations.” — Jason Farago, New York Times, Nov 17 2017.

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.