The Eat-Lancet Commission has released the 2.0 update to its report on the future of the food system and the Planetary Health Diet. Here are the big takeaways.

Six years after releasing one of the most influential reports on the food system, the Eat-Lancet Commission has published an updated version highlighting the biggest challenges facing dietary transformation.

The 2.0 report outlines the benefits of the plant-rich Planetary Health Diet first devised in 2019, emphasising a reduction in meat consumption and an increase in fruits, vegetables and plant proteins for a just, healthy and sustainable food system.

It warns that food is the largest driver of the transgression of five planetary boundaries, noting that even if we phase out fossil fuels, the agrifood sector will alone breach the 1.5°C limit set by the Paris Agreement.

The Commission suggests that governments are largely absent when it comes to effecting change, while corporate powers are exercised in a way that undermines public interests.

“We are at a global crossroads, and governments, businesses, civil society, and individuals all have a role to play in realigning food systems for the benefit of all people and the planet,” says Walter C Willett, co-chair of the Eat-Lancet Commission, and an epidemiologist and nutrition professor at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health.

Here are the key takeaways from the 2025 Eat-Lancet report.

Planetary Health Diet is good for people and the planet

The report reinforces the Planetary Health Diet, which calls for a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes and plant-based proteins, with moderate amounts of meat, dairy, added sugar, saturated fat, and salt. In a nod to the war between tallow and seed oils, the Commission’s new evidence supports emphasising “unsaturated plant oils over saturated fats”.

The Commission notes that the guideline is entirely based on health effects, though there’s good evidence that it would lower the climate impact of most current diets.

Evidence shows that this diet helps lower the risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, several cancers, dementia, obesity and depression, helping prevent around 15 million premature deaths a year (or 27% of the global total).

A shift towards the Planetary Health Diet would lead to a 42% cut in antimicrobial use due to a decrease in animal protein production, helping combat antimicrobial resistance. Plus, it would curb biocide contamination and nitrogen pollution of drinking water, and lower emissions by 15% by 2050.

That said, combining healthy diets with more efficient agricultural productivity and a reduction in food waste is the most ideal way forward, collectively slashing emissions by 20% by mid-century.

Red meat is a villain

Beef, pork and lamb may be high in protein, heme and some minerals, but the cons far outweigh these pros. Red meat is high in saturated fat and cholesterol, and compared to plant-based protein sources, increases blood levels of LDL cholesterol and the risk of heart disease.

Additionally, these animal proteins have been linked with an elevated risk of type 2 diabetes, unhealthy weight gain and mortality in countries that have been overconsuming them for many decades.

It’s why the Planetary Health Diet suggests limiting red meat intake to just 15g a day, or one serving a week. In contrast, legumes, nuts and seeds are a healthy source of protein, and people should eat 125g of them every day.

The transformation to this diet would require a 33% decrease in red meat production and a 63% growth in fruits, vegetables, and nuts, according to the Commission.

Animal proteins are the major cause of agricultural emissions

The food system generates around 30% of global emissions, split into farming, land conversion, and supply chains (a third each).

Most agricultural emissions come from animal proteins, primarily meat and poultry, due to enteric fermentation and manure management. Further, cattle farming is the leading driver of land use change; in fact, 37% of the world’s land is used for agriculture, two-thirds of which is covered by animal grazing.

The Commission outlined three future pathways for 2050. Under a business-as-usual scenario, temperatures would rise by 2°C above preindustrial levels, with greenhouse gas emissions up by 33%, water consumption by 13%, and land use by 4%.

Under the Eat-Lancet transformation (which combines healthy diets, productivity gains, and halved food waste), emissions could be lowered by 20% and land use by 7%. Moreover, food would become more affordable, with the share of income spent on food falling from 7% to 4% globally.

The report looked at another scenario titled Eat-Lancet Mitigation, too, which pairs the above with ambitious climate policies. This would have the biggest benefit, reducing emissions by 34% and land use by 14%, thanks to decreases in ruminant (-37%), non-ruminant (-35%) and dairy (-15%) production.

The Commission proposed keeping annual food system emissions below five gigatonnes by 2050 to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. Eat-Lancet’s scenario alone would meet the threshold by cutting emissions by 60% compared to the business-as-usual pathway, while complementary climate policies would take this even further.

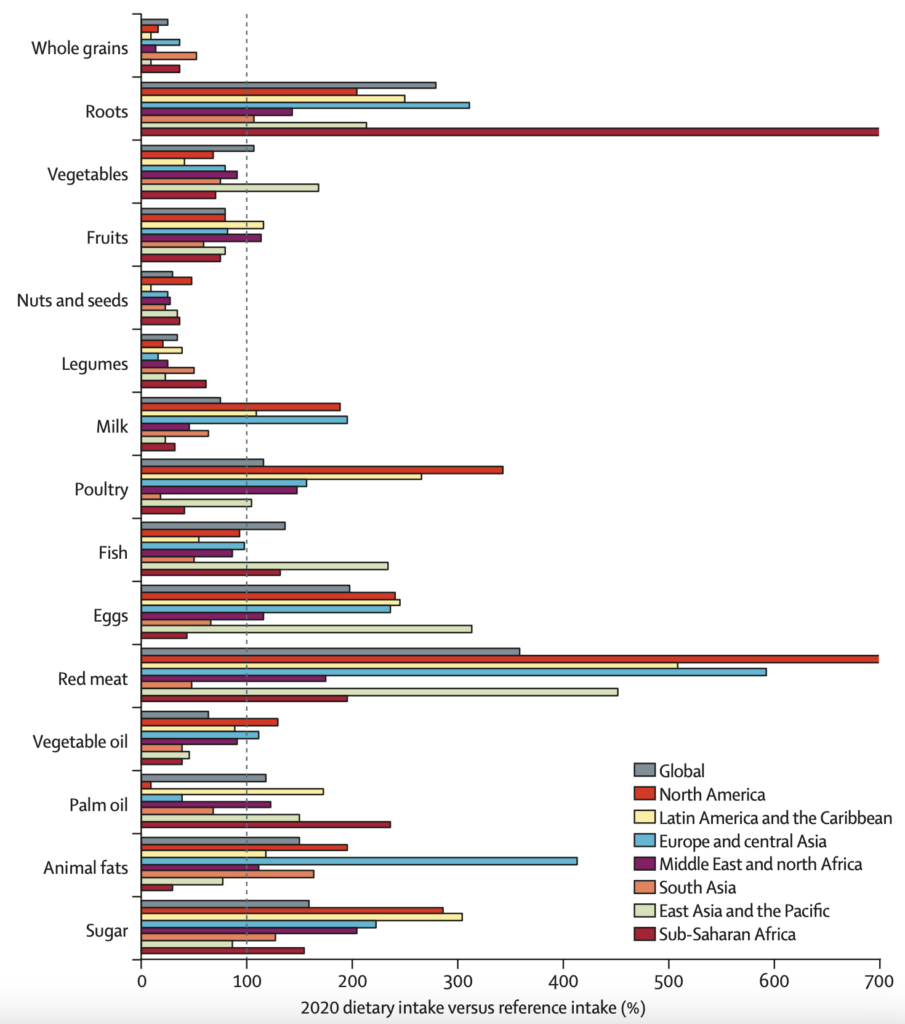

Where are unhealthy diets most prevalent?

Less than 1% of the world’s population is currently in a “safe and just space”, where their rights and food needs are met within planetary boundaries. And 3.7 billion people live below social foundations, while 6.9 billion have diets that would breach planetary limits if adopted globally.

However, the richest 30% of people drive over 70% of food-related environmental impacts, according to the report. And while food justice requires healthy diets to become more affordable – which will be the case as economies and family incomes grow – this will not necessarily result in healthier diets.

Ultra-processed foods, red meat, and sugary beverages will continue to be more accessible, while exposure to unhealthy food advertising will increase. So globally, diet quality is lowest in upper-middle-income and high-income countries (HICs), particularly among men, while rates of overweight and obesity are highest in these same regions, particularly among women.

But healthy diets remain unaffordable for many within wealthy countries, resulting in lower quality and higher obesity among low-income populations living in these nations.

The report suggests that middle-income countries are also where most of the world’s people live and most population growth will occur, so the availability and affordability of healthy diets are of “critical global importance”.

Planetary Health Diet is a threat to the livestock sector

Investigations have shown that the meat industry is already planning its backlash on the 2.0 report, in a similar vein to its reaction to the first edition. The Eat-Lancet Commission knows this.

It cites the sponsorship of scientific studies that align with the sector’s interests as an avenue of corporate influence, alongside “the dissemination of misinformation aimed at discrediting independent scientific evidence – such as in cases involving scientists sponsored by the meat industry”,

Here’s why: to match nutritionally healthy meat consumption, the number of cattle farmed globally would decline by 26%, dairy cows by 4%, and poultry and pigs by 19% by 2050. This would correspond to a 43% decline in production across the terrestrial livestock sector, equivalent to $650B and resulting in a halving of employment numbers.

“The meat and dairy sectors are the most affected by shifts to healthy diets,” the report says. “Although we recognise the contentious and complex nature of animal-sourced food production and consumption, a smaller livestock sector creates opportunities to improve animal health and wellbeing, environmental outcomes, and labour quality.”

The Commission outlines several opportunities and considerations for the industry to navigate this transition, from gains in efficiency and technology and animal welfare to nature-positive rangeland management and integrating plant and animal production systems.

Are meat alternatives a viable solution?

The Eat-Lancet report notes how plant-based, fermentation-derived and cultivated meat provide alternatives to both meat and traditional plant proteins, which consumers may find difficult to adopt due to convenience, culture and taste barriers.

It confirms that plant-based alternatives have “substantially lower environmental impacts compared with meat”, whereas cultivated meat and microbial proteins could be more polluting, but still less so than meat (or at similar levels). This mainly depends on the use of renewable energy sources, which studies have shown can drastically reduce the climate impact of novel proteins.

Plant-based meat products that have high amounts of legumes, vegetables and nuts have favourable nutritional profiles, thanks to an increased intake of fibre and folate, and reduced saturated fat consumption, the Commission says.

However, some of these products have high amounts of salt or saturated fat, and further research is needed on the bioavailability of vitamins and minerals.

From a food justice perspective, there’s a question mark about the price of meat analogues – although rising meat prices are already making many plant-based options cheaper than animal proteins. This industry may also generate and shift employment from rural to urban areas, while market consolidation remains a concern as large multinationals enter this market.

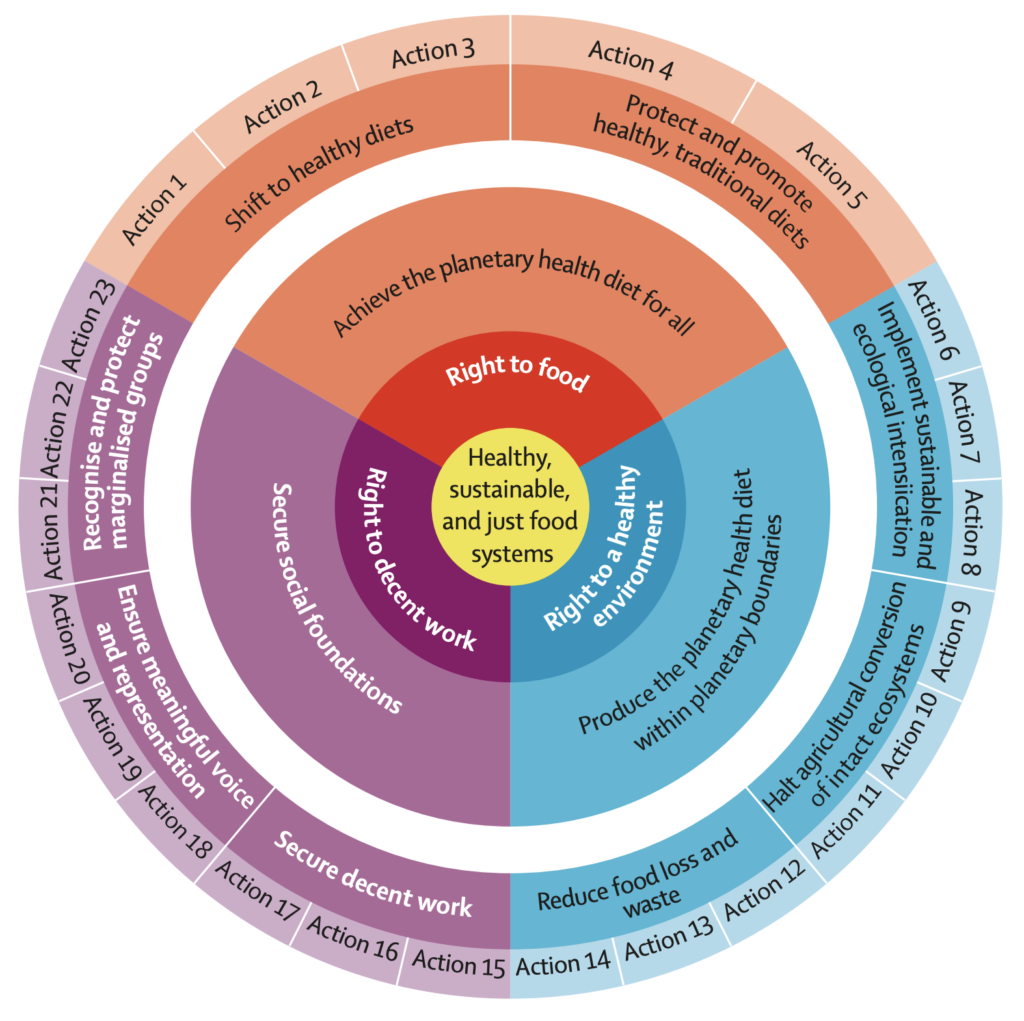

The three key goals set out by Eat-Lancet report

The Commission identifies three primary goals, divided into eight solutions, to benefit public, planetary and societal health simultaneously.

The first involves achieving the Planetary Health Diet for all. This can be done by combining taxes on unhealthy foods with subsidies for nutritious ones, boosting living wages and employment, integrating the recommendations into dietary guidelines and linking them to schools, and supporting local, underconsumed produce, nuts and legumes.

The Planetary Health Diet must also be produced within planetary boundaries. This can be done by improving yield efficiencies and curbing pollution, reorienting subsidies towards plant-rich food systems, halting land conversion of intact ecosystems, and reducing food loss and waste across the supply chain.

Finally, we need to secure social foundations. Child and forced labour need to be banned, and workers must be protected from pollution. Marginalised groups must be secured with broad protections like school meals, disability support, and maternity benefits. And there should be more transparency around research funding and lobbying.

Political leadership over healthy and sustainable diets is lacking

According to the Eat-Lancet Commission, politicians have been “notably absent” in driving transformative food policy agendas and committing resources to long-term change.

Short electrical cycles discourage support for policies whose benefits are realised over a single term, which is compounded by the need for substantial upfront investments and the risks they pose to employment and inflation.

Government subsidies often favour large corporate actors over public welfare, and current arrangements “fail to systematically address and integrate agriculture and the environment, health and nutrition, infrastructure, energy, growth, and equity” into policies.

Governance issues are further complicated by the high degree of corporate concentration in the food industry, which has considerable power and resources to block initiatives that don’t meet business interests.

“Corporate actors use tactics such as directly lobbying governmental officials to undermine political priorities, including dietary guidelines and regulatory intervention,” says the Commission.

These issues are the two primary barriers to food systems change, addressing which is part of a wider set of transformation roadmaps outlined by the report. These include establishing context-specific policies for different regions, setting and tracking targets for shared accountability, building a coalition of diverse actors, and unlocking finance at scale.

The Eat-Lancet report says the sector’s transformation would need up to $500B annually until 2050 – but the benefits that would bring amount to over $5T a year.

“We now have robust global guardrails for food systems, and a reference point that policymakers, businesses, and citizens can act on together,” says Johan Rockström, co-chair of the Commission and director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

“The evidence is undeniable: transforming food systems is not only possible, it’s essential to securing a safe, just, and sustainable future for all.”

The post Richest 30% Drive 70% of Food Climate Costs: Eat-Lancet 2.0 appeared first on Green Queen.

This post was originally published on Green Queen.