The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has published a new standard for plant-based food labelling, which experts say could bolster consumer confidence.

While Europe once again debates whether plant-based burgers can be called burgers, the global authority on product nomenclature has decided to clear things up.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO), whose logo appears on products across more than 25,000 categories, has published a global labelling standard for plant-based food.

The document defines the criteria for the labelling of animal-free manufactured foods and ingredients, but not unprocessed plants, pet food, animal feed, or packaging materials.

It is set to promote “clarity, consistency, and consumer trust”, according to food awareness organisation ProVeg International, which was part of the working group that developed the standard over a three-year period. Further, the ISO standard would help withstand pressure from animal industry stakeholders, it said.

“ISO standards are drafted by an international working group of experts from companies and NGOs around the world, with feedback from so-called ‘mirror committees’ from national standardisation organisations,” ProVeg’s Martine van Haperen, who represented the organisation in the ISO working group, told Green Queen.

“After multiple iterations of feedback, the draft is then sent out for voting to the mirror committees. If a majority of the committees votes in favour, it will be adopted as an ISO standard.”

“Previously, there was no internationally recognised guideline on how the claim ‘plant-based’ can be used. Most countries also don’t have national legislation about this,” she said. “As a result, foods containing animal ingredients have been occasionally labelled as ‘plant-based’, which risks confusing consumers and damaging their trust in this claim.

“The ISO standard provides guidance for manufacturers and retailers worldwide to preserve and promote ‘plant-based’ as a claim that is widely trusted and appreciated by consumers.”

ISO standard covers cultivated meat and fermentation too

The ISO says its document can be used in B2B and B2C communications, food labelling and claims, international trade, and by competent authorities and enforcement agencies.

“It is recognised that the category of plant-based foods as a whole is diverse and includes many foods for which there are no animal equivalents. Therefore, this document does not assume that plant-based foods are replacements for animal-based foods exclusively,” it writes.

It covers two types of products. Category One entails plant-based foods with no animal ingredients. These products must have a characterising plant-based ingredient, like legumes, nuts, vegetables or fruit and can be labelled ‘plant-based’.

Moreover, this category lets companies use the term for microbial-fermentation-derived egg and dairy products. The question is: could this be misleading to consumers? “For products like a mushroom burger or mycoprotein, I think that makes a lot of sense,” argued van Haperen. “Most consumers probably already think about these as ‘made from plants’, even though fungi are technically not part of the plant kingdom.”

However, she added: “For ingredients like precision-fermented whey and casein, it could be confusing. I therefore expect most brands will be reluctant to put a ‘plant-based’ label on their precision-fermented dairy. Just because ISO allows it doesn’t mean that manufacturers will actually do it.”

In Category Two, ISO defines products containing plants as well as “limited and conditional use of animal ingredients”. These can’t be labelled ‘plant-based’, instead requiring a qualifier like ‘plant-based vegetarian’ or alternatives like ‘plant-strong’.

The animal-derived elements would need to serve a technological purpose here, and are limited to 5% of the product’s combination. Additionally, only ingredients taken from living animals – like milk, eggs or cultivated meat produced with live cell lines – can be used.

“Some examples of products that would fit the second category would be a soup mix with lactose added as a carrier for the flavouring, a margarine with vitamin D from sheep’s wool, or fruit-filled puff pastry with egg wash,” explained van Haperen.

“Cultivated meat is allowed to be part of the 5% animal ingredients, so we could, for instance, see a ‘plant-strong’ soy nugget with a small amount of cultivated chicken fat added for flavour and texture.

Manufacturers can choose how to label products in this second group, though the use of animal-derived ingredients must be highlighted clearly and transparently on the packaging label to avoid misleading shoppers.

By defining ‘plant-based’ for products devoid of animal ingredients in the first category, the ISO standard enables brands to use the term “confidently and credibly”, which boosts consumer trust, marketing claims, and purchase intent, according to ProVeg.

A first step towards government legislation?

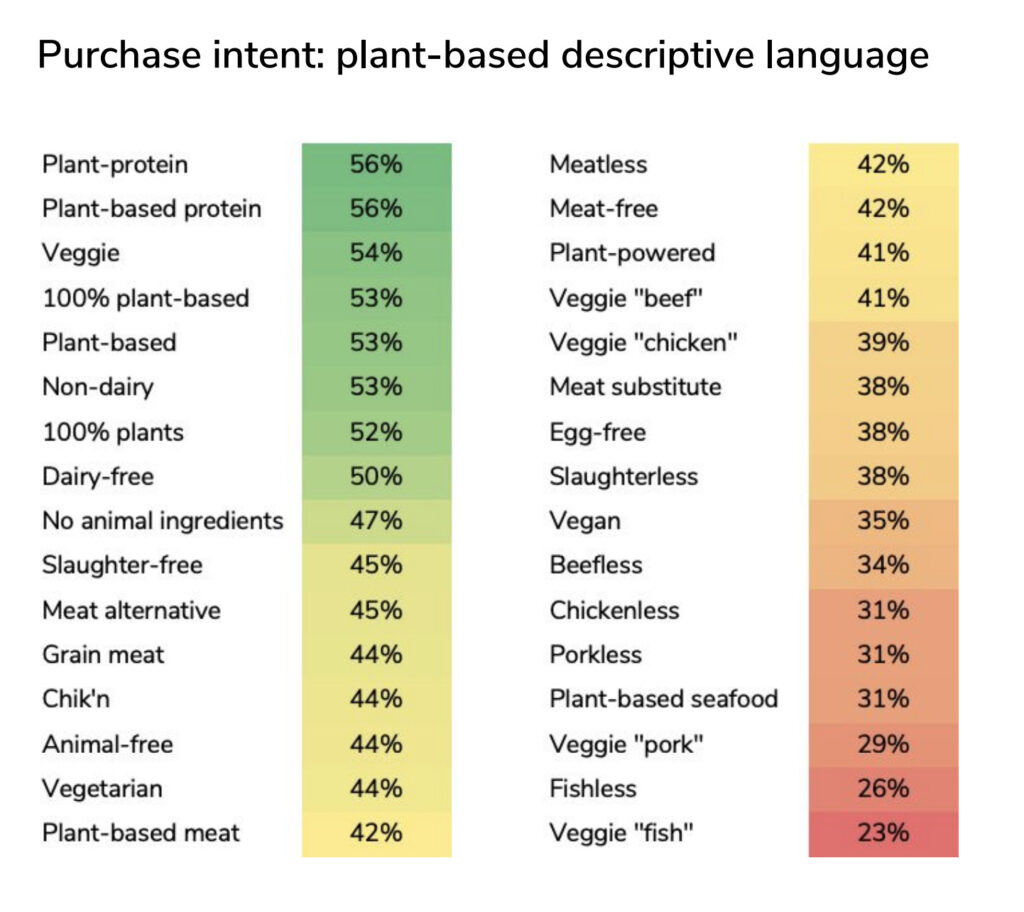

One of the major talking points of the ISO standard is the preference for the term ‘plant-based’ over ‘vegan’, which has been found to alienate some consumers.

A 2019 survey by the Good Food Institute found ‘plant-based’ appealed to 53% of consumers, but ‘vegan’ to just 35%. Those perceptions have persisted – last year, a YouGov poll revealed that Brits preferred the former term to the latter.

ProVeg advised brands to use ‘vegan’ on the back of packaging as a tactic to keep flexitarians interested – since it’s common among vegans to check the back-of-pack labels anyway, this would give them the information they need too.

Products that meet the ISO’s first category will have the clearest path to labelling as ‘plant-based’ and thus are likely to enjoy stronger consumer trust and broader market appeal, according to ProVeg. And to enhance clarity, brands could use terms like ‘100% plant-based’.

“Adherence to ISO standards is voluntary, so we need to wait and see how this standard is received and implemented across various cultural, economic, and political spaces,” said van Haperen. “However, ISO is a widely respected institute, and this standard was created with input from food industry partners and NGOs around the world, so I expect it to have a profound impact.”

She added: “There was some tension between stakeholders who wanted the option to use animal ingredients in plant-based products and those who wanted them to be completely free from animal ingredients. The final standard is a compromise to satisfy both sides.”

The ISO standard is likely to influence future national regulations, corporate labelling practices, and retailer policies globally. “It could be a first step towards governmental legislation regarding the labelling of plant-based foods, further solidifying consumer trust in this product claim,” said van Haperen.

“The standard also supports broader goals of global harmonisation in food labelling and reduces the risk of greenwashing, especially in markets with evolving regulatory landscapes. Its legitimacy as an ISO standard offers a powerful reference point for companies and advocates working to shape national policy.”

Shortly after the standard was published, the EU took a major step back in its regulation of plant-based labelling, with the Parliament’s agriculture committee voting to ban the use of meat-like terms on vegan alternatives, paving the way for the bloc to overturn a 2020 vote against such a restriction.

The post Can This New International Standard Transform Plant-Based Food Labelling? appeared first on Green Queen.

This post was originally published on Green Queen.