Kate Scott, Director of the Madrean Archipelago wildlife center. Michel Marizco/KJZZ

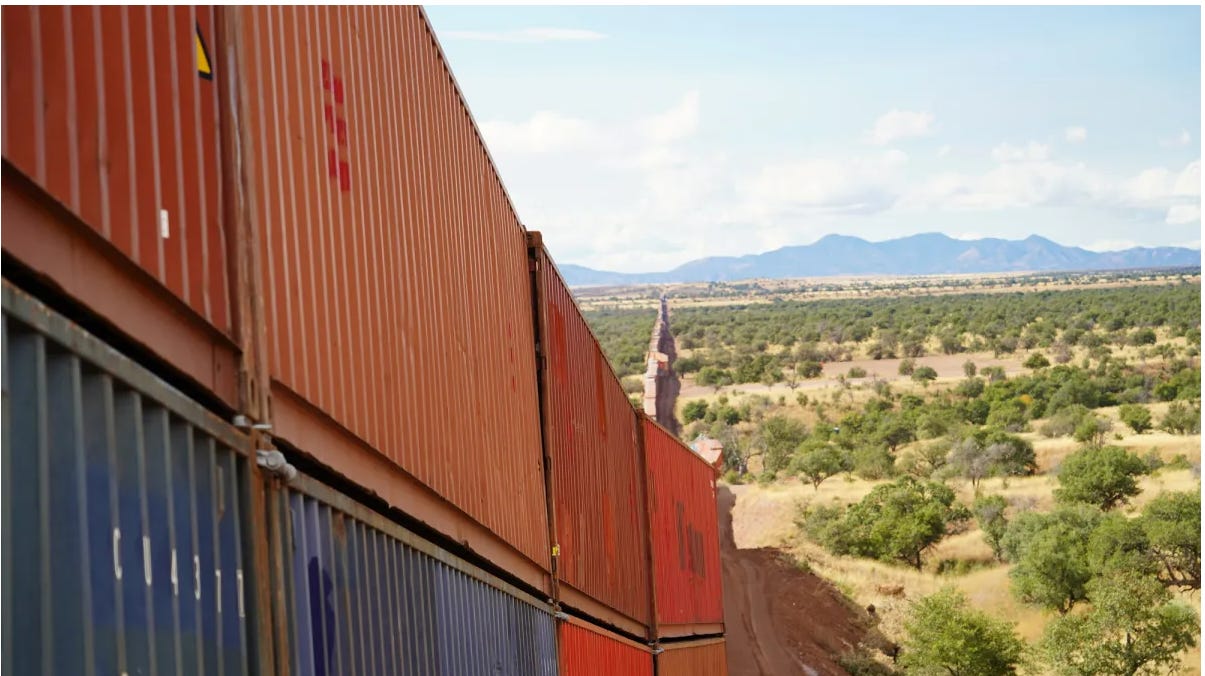

Pieces of old vehicle barrier were pushed into canyons. Other heavy, broken pieces were left on ledges and used to form a welded together gate blocking access to the remainder of the border road. Broken and flattened culvert pipe scattered across the grasslands.

“And everywhere that this was done, there has been created what I simply call mine tailings,” Scott said.

Under former President Donald Trump, contractors built more than 20 miles of border wall in this area. The wall is just a part of the project; roads were widened, hills flattened and vegetation destroyed to reach the international border. Gaps in the fence remain. The border wall was being painted up until this year. Now, shiny black coating abuts lengths of rusting border wall.

“So you have this infrastructure leading up to the wall and all along the wall. And it’s at the same level of devastation. This is a tiny little snapshot of one,” Scott said.

Forget about waiting until Nov. 12, on my Lincoln County, Oregon Coast radio show, Finding Fringe, because DV readers get the interview here now! And I’ve written about my upbringing in the desert around Tucson, my work as a newspaper cub reporter in Southern Arizona and Northern Mexico, my crazy days diving the waters of the Sea of Cortez, and my other work along the border, in El Paso, in Chihuahua.

“Wrestling the Blind, Chasing Apache Horses, and Unpacking the Vietnam War,” Cirque Journal, by Paul Haeder

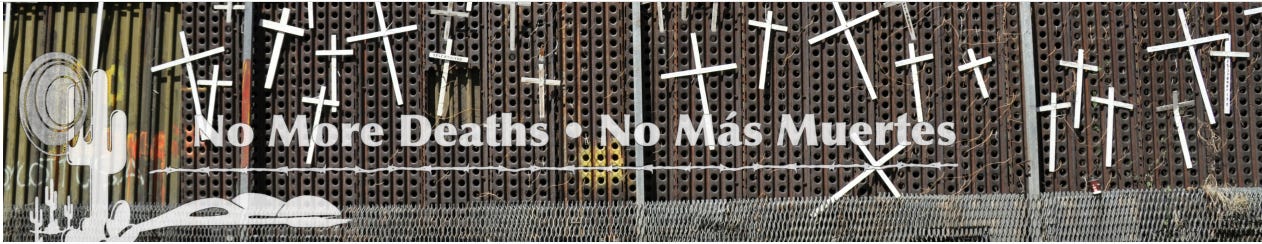

People have been dying in the desert for decades because U.S. policy deliberately funnels them there.

Unaccompanied children in the custody of the U.S. Border Patrol on March 17, 2021. Jaime Rodriguez Sr./U.S. Customs and Border Patrol

The Madrean Archipelago Wildlife Center is helping wildlife by restoring and preserving Birdland Ranch, a remote wildlife area and biodiversity hotspot, home locally to 154 bird species, endangered top predators, neotropical birds and more in a rich ecosystem.

“The nearby San Pedro River corridor supports two-thirds of the avian diversity of the entire United States, including more than 100 species of breeding birds and 300 migrant birds.” (R.J. Luce, pg 3, San Pedro Anthology) Wildlife infrastructure projects include maintaining and upgrading an extensive cavity nest-box trail to preserve threatened species, habitat restoration, as well as plans to restore a small historic outbuilding for community outreach events.

Questioner: So my question is how do we interrogate our savior complex, while also acknowledging these tremendous emotions of love and loss?

Tiokasin Ghosthorse It’s a great question, and thanks for that little challenge. I was kind of waiting for that. That’s great. Thank you for that Ayana. Well, you know, in the original intuition of Lakota language, intuition of all of us I would say – without any filters of what intuition is by giving a definition, from this perspective of the Western mind, which I’ve been educated in and as Robert Clemens or Mark Twain said, It took me years to get over it, right? So when I’m thinking about what happens when we lose contact, we lose relationship with the Earth, we are constantly looking for that search, for ourselves, in others, and it gives way, because of our loss of instruction, it gives way to the fact that somebody else can come and rescue us. And when I think about, the original instructions, the original intuition, is the fact that even today, people go out to the wild, go out to nature, go someplace hidden, to heal, basically to understand and usually it’s this sort of benevolence of I can go to the wild, to the Earth, to nature, to listen. And when I think about that, it’s well, I think it’s different. When we were taught as young people that we can, yes, we can go to the Earth and mother nature to listen, but in that, in the fullness of the thought, where most Indigenous peoples kind of, you know, look at that wonderment and what do you mean going to the Earth and listening for lessons actually. And then what we understand is, as one Native person, I would just say it this way, is that we usually have gone to the Earth, to find out how Mother Earth is listening to us. And that takes a lifetime, it just doesn’t come up with a cause and effect.

You know, we go we get rewarded, we come back, and then we have the answer – the solution. So I think the savior mentality is tied up in the cause and effect of, we have solutions to save, what we can have our, possessive, our environment, our climate, our Earth, our – everything is possessive. And so when it comes to the savior mentality, the salvation point mentality, it’s that there is always going to be salvation for us as long as we follow the rules and regulations of an authority figure, religion, science, or government. And all of those have authority figures, where you look at it the other way, in relational languages, and in Indigenous languages, there is no need for monotheism or authority. Because that domination does not fit authority, well, it does actually domination and authority go together, but domination does not fit relational languages, and in relational languages, everything is in scope, everything is relative, everything is related. And there’s no need to get connected, or even save that which giving you all the answers, meeting all your needs as Mother Earth does.

So Mother Earth does indeed listen to us and gives us all that we need all our cries, all our whimpers, all our prayers, she answers it, gives us food, gives us water, gives us warmth, and we learn in between those like warm and cold, we learn what the balance is, we learn what the rhythm is. And so once we are into the rhythm, you can really start questioning, what is savior mentality? What is salvation point mentality? We’re always looking for the solution. So I think rather than looking for this solution, we need to acknowledge where we are at in this consciousness, or in this continuum of being in the present and this comes through when you speak your Indigenous language and most Indigenous languages that I know of, don’t have nouns. So therefore there cannot be a savior mentality.

Now you see how the western mind tries to take all of what I just said and put it into the box of, I need to find the answer to why is this? We need a reference, we need something so that we can learn “how to”, as if how to was a manual to do something. And what we’ve forgotten is that Mother Earth is always listening to us, Mother Earth is always teaching us lessons. There’s not one time in human history, that humans can teach Mother Earth, any lesson, you see. And so that’s our arrogance to think that we can control the Earth, we can, you know, do what we want to the Earth, and even save the Earth. And so in that sense, you know, the Western mind, the Euro-Western wants to be at the top of the heap so that they can, I don’t know what it is, reward, cause and effect, take and reward, or give and reward type of mentality, a dualism. And you see that Mother Earth is not like that, very many qualities of communication she has. So I guess that’s a long way of understanding or trying to answer the question of what is savior mentality.

TUCSON, Ariz.—The Trump administration is muscling forward with plans to wall off a critical international wildlife corridor, setting up construction camps to erect a 30-foot barrier along one of the few remaining gaps on the U.S.-Mexico border.

“It’s super concerning that with the technology we have available today we are using a type of border security that is so detrimental to wildlife,” said Susan Malusa, a Catholic biogeographer who heads the University of Arizona’s nonprofit Wild Cat Research and Conservation Center that detected the jaguar earlier this month.

“We have deep social responsibilities not to use and lose our Earth,” said Malusa, who also holds a master’s degree in theology. “This is not only a Catholic idea. We do not get to judge what can be expendable as a species.”

[Demonstrators on both sides of the border in the San Rafael Valley protested plans for a new wall in May with cardboard cutouts to symbolize local biodiversity.Credit…Rebecca Noble/Reuters]

As it stands, fences are piecemeal and violent. And historically, Republicans have been less inclined to build them than Democrats. There are currently 700 miles of non-contiguous fences along the 1,951-mile border. A Republican built most of those, but we cannot ignore that Democrats have also built and supported their fair share, showing bipartisan commitment to this symbol of illusory control. Biden has not made an about-face, he is simply continuing an interminable trend of border-building policies and now, like many who came before him, he has fallen into the same, familiar, repetitive pattern.

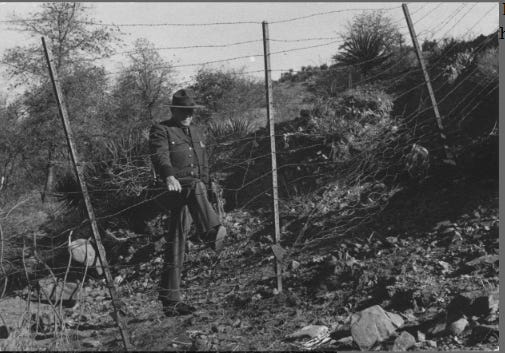

The first border fences built along the U.S.-Mexico border to curb immigration from Mexico began in earnest under Democrats Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman. After building fences for decades to stop animals, the federal government shifted its focus when people began migrating in significant numbers from south to north in the 1940s and 1950s.

Treacherous Terrain: Racial Exclusion and Environmental Control at the U.S.-Mexico Border — Mary E. Mendoza

On a brisk autumn day, agents patrolling the US-Mexico border near Mexicali caught Trinidad Hernández Iglesias, a coyote, or human trafficker, who had been sneaking people across the line. At the time, Iglesias had been a target for the patrol for about four years, and his capture was an enormous victory. Over the years, he had sold a number of fraudulent American documents to Mexican citizens who had paid him to help them navigate the difficult environment of the borderlands and help them cross the border in one piece. He assured them that with his documents they would be able enter the United States as American citizens and safely “get through the fence at the international border.”1

After his capture, newspapers in Mexico covered the story, noting that the sixty-five-year-old coyote had been a well-known smuggler with “notable ingenuity and charisma.”2 Originally from Jalpa, Zacatecas, a town far to the interior of Mexico, Iglesias had moved north, learned what it took to cross the border, and then made a business out of smuggling people across it. Although he only confessed to smuggling six people into the United States, reporters had reason to believe Iglesias had sold documents and helped “many others that had entered the [United States].”3

In spite of the many people successfully smuggled by Iglesias and other coyotes, it is well known that migrants have not always made it across the line. Many cannot afford the fraudulent documents or the help of a guide like Iglesias, so they have made the journey on their own—a journey that, too often, ends fatally. Just one year before officials caught Iglesias, border agents found the body of a young boy named Nino Héctor Martínez along with the body of an unidentified Mexican woman at the Texas-Mexico line. Martínez had been trying to get across the dangerous Rio Grande with his father when something went wrong and he drowned. It is not clear whether the woman crossing the border knew Martínez and his father or not, but these two casualties—the woman and the boy—are just two among many who have died traversing the dangerous terrain along the US-Mexico divide.

These two incidents, Iglesias’s arrest and the deaths of the Mexican woman and boy, took place in 1950 and 1951, and yet they could have appeared in the newspaper this morning. Surreptitious crossing and death are nothing new along the US-Mexico boundary. They are continuous realities despite dramatic changes over the course of the last century. Once an open range, the border landscape has morphed into a series of fences, checkpoints, watchtowers, stadium lighting, and other infrastructure for policing. This growing technological management of the border has been accompanied by US immigration policies that have become more exclusionary over time, from Chinese exclusion in the 1880s to the National Origins Act in 1924 that limited the number of immigrants who could enter the United States from the Eastern Hemisphere, to the Immigration Act of 1965 that set limits for nations across the globe, to an attempted ban on Muslims in 2017. Change at the border, in other words, has mirrored the growing exclusionary policies enacted at the federal level. In spite of the massive changes made to border infrastructure, migration across the line persists, making the borderlands a place of both change and continuity.

Continuing a long trend of building up the border, Donald J. Trump proposed in June 2017 to build a solar wall along the length of the Mexican border. His planned wall has been both praised and criticized by environmentalists. Those in favor of it argue that it could help alleviate the rising need for clean energy and thus ultimately help fight climate change.4 Those who oppose it note that the clean energy it might produce will not outweigh the damage it will do to the important natural ecosystems along the border.5 However, few, if any, of the articles about the environmental impacts of this fence discuss the ways in which it would continue to force human migrants to pay coyotes like Iglesias to help them or else try to cross dangerous landscapes that threaten their lives.

In the context of this larger history of construction at the border, past and present building projects provide an opportunity to look to history to understand potential outcomes of Trump’s proposed wall: put simply, history tells us that it will not work and that it will do more damage than good. This latest fence proposal, though, the one that promises to provide clean energy while also handling the so-called immigration problems in the United States, also exposes a central, long-standing, and hidden tension between border fence construction and environmental manipulation. In every phase of construction, arguments for environmental control have consistently worked to the detriment of human migrants, hardened racial divisions, and reinforced social hierarchies. In other words, the tension between racialized exclusion and efforts at environmental control are nothing new.

The first construction projects at the border had little to do with human migration but were, at their core, attempts to control the natural environment. In 1906 the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) oversaw a massive eradication campaign for a tick that had caused hundreds of cattle in the northern grazing lands of the United States to become sick and die. After pushing the tick south for several years, the USDA set up quarantine stations at the US-Mexico border to screen, disinfect, and quarantine cattle to avoid the tick’s reentry. The cumbersome policies created significant controversy among cattle ranchers in the United States whose cattle wandered into Mexico. Because the USDA forced these cowboys to comply with the same quarantine measures as Mexican ranchers who wanted to export their cattle to the United States, American ranchers began to describe and conceive of “Mexican cattle” as filthy and diseased in contradistinction to their “American cattle.” American cattle, they argued, should not have to go through the same quarantine measures as Mexican cattle, even if they wandered south of the border. Put succinctly, the ranchers’ frustration with the quarantine measure created a powerful discourse about race at the border, even if humans were not those being racialized.6 This controversy also resulted in the first federally funded border fence, constructed in 1911.

Environmental concern and control, then, provided a fertile context for hardening racial categories along the US-Mexico border. With new protocol for the movement of cattle, ranchers created a discourse about Mexican animals and bugs as diseased and dangerous. To control those menaces, the USDA built fences and checkpoints along the border to search for and eradicate those threats. Later, US citizens and government officials adopted and applied earlier discourses about bugs and animals to human beings. 7 By the middle of the twentieth century, it was the Mexican human body that became the invasive pest, and fences became one of many tools for changing the nature of human migration.

The Bracero Program, a guest-worker program that facilitated the migration of Mexican workers into the United States as short-term contract laborers from 1942 to 1964, transformed the border from a place that had been relatively open to Mexican migrants to one that was increasingly closed to them. Many scholars argue that the program ultimately created two streams of migrants: one sanctioned (young healthy men who became braceros) and one unsanctioned (any person who did not qualify for the program but tried to cross the border anyway).8 South of the border, Mexican officials and landowners worried that a mass exodus of laborers would deplete the labor force and damage the economy.9 North of the border, Americans feared a virtual Mexican takeover. In January 1954, William F. Kelly, the assistant commissioner for the US Border Patrol described the influx of Mexican workers as “the growth of a social fungus that infects any who come in contact with it.” Mexican immigration, he said, was “the greatest peacetime invasion ever complacently suffered by any country.”10 Concerns north and south of the border led both Mexican and American officials to increase patrols along the US-Mexico border and look to other ways to curb unsanctioned migration. By the late 1940s, the Immigration and Naturalization Service, overseen by the US Department of Justice, built the first fences along the boundary meant to control human migration. Fences previously used for cattle became tools used to control and herd humans. Since then, fences have evolved from barbed wire to chain link, then to wire mesh, large metal landing strips, and large steel bollards erupting out of the ground.11

At the same time that Congress worked to place this cap on migration, a burgeoning environmental movement began making seminal contributions to rhetoric about restricting immigration. In 1968 the Sierra Club published Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb that essentially argued too many people in the United States would place unsustainable demands on US resources.12 In the years following the publication, John Tanton, a staunch supporter of immigration restriction in the name of environmental sustainability, chaired the club.13 These views, coming from such an influential environmental organization, reframed the environmental debate from one that pitted humankind against nature to one that pitted immigrants and their migration as the antithesis to a sustainable environment.

Through the 1980s, 1990s, and into the twenty-first century, this immigrant versus nature narrative continued to permeate environmental debate in the US-Mexico borderlands. In southern Arizona, this became particularly evident in the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, a wilderness area that hosts “a thriving community of plants and animals.”14 The monument, designated as such in 1937, deemed an international Biosphere Preserve in 1976, and then given official wilderness status in 1978, was a place of increasing concern for environmentalists.15 As early as the 1940s, the National Parks Service (NPS) had worked with other US agencies to block access to the land in the name of conservation, specifically to keep cattle from wandering into the monument.16 But as fences and other structures sprouted all along the US-Mexico border, the NPS saw an increase in the number of human migrants funneled through parts of the monument’s 500 square miles of fragile desert ecosystems to make the trek.

By the early 2000s, concerns about the ecological health of the monument and debates about national security and immigration were inextricably linked. One so-called green activist organization, Desert Invasion, held tightly to the immigrant versus nature rhetoric seen in earlier Sierra Club publications. “Our Fragile National Monuments, National Wildlife Refuges, and National Forests along the U.S. Southern Border,” its website reads, “are being annihilated—not by natural forces or by unwitting tourists, but instead by an overwhelming number of illegal aliens.”17

The environment became central to some arguments for building up the border to stop people who walked through the desert landscape, stomping over vegetation and leaving garbage in their wake. A study from 2007 concluded that at that time, an average of fifteen hundred migrants passed through the Arizona-Sonora border daily, each leaving roughly 9 pounds of waste behind them. The study thus alleged that migrants left 13,500 pounds of garbage per day in the Arizona-Sonora region alone.18 Moreover, that study claimed that shifting migrant patterns had severely impacted vegetation growth. The limited growth increased erosion and changed runoff pathways for rainwater. Finally, it pointed out that increased human presence also disrupted animal life and likely put endangered species at risk of being killed for human consumption.19 In short, migration through the monument was destroying it, but fences could help funnel traffic elsewhere.

On the other side of the debate, organizations like The Nature Conservancy fought hard against fence construction and, by 2009, they had challenged the Department of Homeland Security in a legal case, arguing that fence construction would destroy habitats.20 In South Texas, for example, the endangered ocelot could be cut off from vital resources and become locally extinct. Curiously absent from articles covering this debate, though, was a concern for those human lives that would be funneled to more dangerous environments.

Built structures along the border have created a hybrid landscape of built and natural environments that have killed thousands of people crossing the border. Fences funnel migrants to deserts, mountains, and rivers where they are forced to fight the harsh elements of those areas. In the Arizona-Sonora desert, the area where Organ Pipe National Monument is located, the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner reported a stark rise in the number of deaths between 1990 and 2005.21 Those deaths continue.22

Whether for or against fence construction, mainstream environmental discourse about border fortification has ignored these human realities and dimensions of border policing and control. In doing so, it has reinforced racial and social hierarchies in the United States. In some instances, arguing for fence construction to save the environment fuels ongoing racialized forms of social exclusion by pushing migrants through deathscapes, where they die from exposure or drown, just as Nino Héctor Martínez did. Those who seek smugglers like Iglesias to help them also risk losing their lives. In July 2017, for instance, up to two hundred people were packed into a tractor-trailer after being smuggled across the border and driven to San Antonio, Texas. Ten of them died of heat exhaustion and thirty others were hospitalized, illustrating “the extremes that people will go to sneak into the United States.”23 In cases where environmentalists argue that fence construction is destroying critical habitats for animals, the lack of acknowledgment of human suffering and death in the borderlands reinforces the enduring notion in the United States that immigrant bodies are expendable, and it raises questions about the value of animal and plant life versus the value of an immigrant life. It also reifies the false dichotomy between nature and culture, ignoring the vast web of socioecological connections in the borderlands because projects of environmental control tend to separate nature from human realities. Rather than approaching the humanitarian crisis and the environmental crisis as one complex web of concerns, policymakers continue to view them as divorced from one another.

Examining the history of environmental control and border fortification exposes the dangers of single-minded approaches to issues related to the environment. Thinking about preserving the flora and fauna of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument or other borderlands habitats, albeit a noble and important effort, is as seductive as it is destructive when it comes to the preservation of human life and dignity. A historical analysis of these issues reveals that the tension between race and environment at the border is nothing new. Change and continuity at the border has always been deeply entangled with environmental issues, and the current political climate suggests that both the environment and the plight of the immigrant will continue to be important issues to consider, but together, not apart. Environmental work must consider who is bearing the burden of efforts at conservation, which is often much more complicated than it seems on the surface.

Notes

Mary E. Mendoza is an assistant professor of history and critical race and ethnic studies at the University of Vermont. She received her PhD from the University of California, Davis, in 2015. Her research focuses on the intersections between environmental and borderlands history and has been funded by the National Science Foundation, the Smithsonian, the Ford Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Huntington Library.

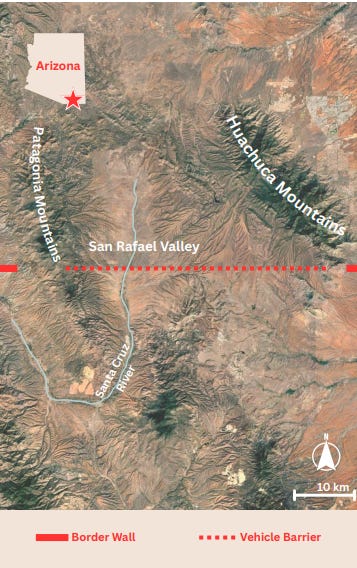

THE SAN RAFAEL VALLEY: WILDLIFE, WATER, AND A WAY OF LIFE AT RISK

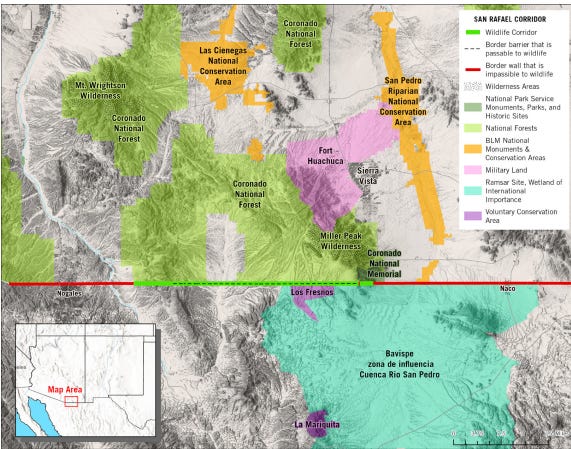

Hundreds of miles of border walls have already severed much of the Arizona–Sonora borderlands, blocking wildlife corridors, fragmenting ecosystems, and pushing endangered species closer to extinction. In the Sky Islands region — one of the most biologically rich and ecologically interconnected wildlands in North America — only a few unwalled cross-border corridors remain. One of the most important of these, the San Rafael Valley, is now in the crosshairs of the Trump administration for immediate new border wall construction.

The San Rafael Valley, a sweeping grassland basin cradled between the Huachuca and Patagonia mountains, is one of the last vital pathways for wildlife movement between Arizona and Sonora. Jaguars, ocelots, black bears, pronghorn and many other species rely on this corridor to move freely between the U.S. and Mexico. The San Rafael wildlife corridor is an ecological lifeline connecting the transboundary Sky Island Mountains.

At least 17 large wildlife species have been documented crossing through existing vehicle barriers or cattle fencing in the San Rafael Valley.This region has seen the highest number of modern jaguar detections anywhere in the U.S. and is home to 17 threatened and endangered species including Sonoran tiger salamanders and Mexican spotted owls, and 9 species with designated critical habitat.

Armed with waivers that override bedrock environmental laws, Trump’s Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is moving at breakneck speed to wall off the San Rafael. In June 2025, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) awarded a more than quarter of a billion dollar contract for border wall construction across the San Rafael Valley to Fisher Sand & Gravel Co — a company with a long record of environmental and regulatory violations, including air quality infractions, criminal charges and millions in fines and settlements — raising serious concerns about the impacts to wildlife and ecosystems in this vital bioregion. The proposed wall would cut across the transboundary watersheds of the San Pedro and Santa Cruz Rivers, fragmenting the hydrology of the corridor.

A barrier here would block species movement, destroy protected habitats, and inflict irreversible damage on critical ecological linkages. It could also bring a wall of artificial light to this Dark Sky landscape — stadium bright illumination that would disrupt nocturnal pollinators like bats and insects, disorient migratory birds, and degrade the valley’s natural light-dark cycle, which governs critical behavioral and physiological processes in wildlife.

This report documents the San Rafael Valley’s biodiversity, the species it sustains, and its indispensable role in the survival of endangered wildlife. It details nine key protected areas linked by the San Rafael Valley wildlife corridor. Finally, it also outlines the severe harms posed by new border wall construction and makes the urgent case for protecting this irreplaceable corridor before it is destroyed. — Destruction of a JAGUAR CORRIDOR … Impending Border Wall Will Sever Vital Pathway for Wildlife in Arizona’s San Rafael Valley

[A black bear obstructed by the new 30-foot-high border wall at the nearby San Pedro River. Credit: Sky Island Alliance]

“People from a bunch of different groups, with different viewpoints, realize they have the power to stop the wall,” says Parker Deighan, a Tucsonan who volunteers with No More Deaths, explaining why she decided to head down to the border to protest the wall early last December.

Tucson people working with the Center for Biological Diversity, the Sky Island Alliance, the Sierra Club, No More Deaths, the Green Valley Samaritans, the anarchist BCC, found common ground to block the construction dividing the border. Community groups and concerned locals from Bisbee, Ajo, and rural parts of Pima and Cochise County joined, too.

“It wasn’t a unified political stance, but a shared goal,” Parker says.

Lest we forget the human toll:

Read Scott’s story:

+—+

A Poet, the Pacific Flyway, and a Sonora Flash Flood*

Memory –

He holds up the sands of mountain heads and tectonic fissures splayed, from peaks like a purple haze over the Old Pueblo he learned are called Madrean sky islands. His hands soothe flecks of iron ore, pulverized by plates crushing and churned into tsunamis of flash floods booming into Sonora from pine and fir quarries forty miles away.

The Oregonian smiles. There is movement all around: the cumulus clouds push shadows onto the raging seasonal river, almost class five whitewater. He smiles again, as gambler’s quail lift and squeak like bad springs on an International, as a tortoise chomps on acacia.

He lets the air take the rivulets of sand before the surge of flashflood crushes part of a cut bank across the wide arroyo where he gladly stands with students. He smiles, pointing.

There is a fragility in the 19 year old recalled, a thin membrane of memory now, 37 years later, holding onto that moment when I was with this poet the first time. Toughed like basalt after the solar blast of a million years. What is forgotten has been chipped away by sun, wind and lichen. I am going back to Stafford.

I think of him, now, this 100th anniversary of his birth, listening to his son Kim, a poet too, a sort of passenger pigeon of his father’s legacy here in Oregon. That singular idea Kim brings forth about his father’s attention to self, to the inner eye, well, it is now the shape of things to come, here in the writing room, and like a miner clanking about a shaft, remembering years ago where that vein was, I remember Stafford from a time when the world was big and ideas endless.

William Stafford, like a thousand poets (or maybe a few hundred), is refracted memory churned into the daily living of writing . . . his practice:

I put my foot in cold water

and hold it there: early mornings

they had to wade through broken ice

to find the traps in the deep channel

with their hands, drag up the chains and

the drowned beaver. The slow current

of the life below tugs at me all day.

When I dream at night, they save a place for me,

no matter how small, somewhere by the fire.

Thirty-seven years later I announce to the library audience in Tigard, Oregon, when Kim Stafford asks for questions, that I know Stafford like a million others know him, or ten thousand maybe personally, or those of us in the tens of hundreds who had a chance to hitch to that thing called the “poetry reading-slash-poetry workshop.” Three times the sound of his voice, in a room and in situ, the virtuoso of the poet teacher – Stafford – crossed paths with my own sheltering sky. That pathway then and later was impressive, an ambassador of poems, leading him to my place of latticed shadows or leveling titanium sky, Tucson, and then the endless journey away from Arizona to New Mexico, onto El Paso, other parts of Texas, on past Bhutan to Istanbul to the Great Wall to Iran.

How many intersections with youth, how many taunts to our young pugnacity, did he shepherd for only a moment in that time as traveling poet? His name is braided to the valley of Willamette, poured into the delta waters of Columbia threading loam and cedar.

The remembering goes backward to Tucson, in the 1970s. Time and dates are flotsam in my life. Was it 1979?

We all turn to the molting tattooed skin of solar blasts . . . some of us semi-wise decades later . . . the shape of his words alive upon his death. I’ve pushed past continental divides when his words locked into conversations with Neruda or Levertov . . . . Crossed equatorial sunrises caught in my own hardening cornea where W.S Merwin chatted with Lorca and Czeslaw Mislov . . . . And this vast ocean reef web I’ve touched with scabbed skin as narcosis sank into me, when the cul-de-sacs of Sappho, Sylvia Plath, Lucille Clifton let their poems grow like dahlias.

The oddest places Stafford’s poetry eddies up from – a cay off Belize with lemon sharks; or the tipping leaves of jungle liter carried by harvester ants in the millions inside the shadow of Copan pyramid.

Yet, even reckless dusks near Hanoi on an intrepid Russian motorcycle or running through Guatemalan hills with the contraband of thieves, all of this is nothing compared to the monumental histories of what a child writes in that early gossamer light, a floating time, when we observe the world at that intersection of nascent knowledge and the wide brow of endless earth. Now, old and entranced by the child, or the stories, or the things the father and sister and mother and children brought to me then, well, he is right to say childhood is the world of the poet.

That’s what William Stafford whispered to us, in three workshops: Most good poetry — maybe even most writing — comes from those first years: the uplifting loneliness in a child’s drama, inside the child’s atmosphere of patina carrying the light. A place where the girl’s take on the tornados that are the world is honored. Or the boy’s yearning to belong to some pattern or some baseball field is captured in song. That weight of poetry is tied to our own clumsy solitary otherness as juveniles, that feeling, as if a snake skin, is all itchy on us, or the wagging coiled tail of an alligator lizard inside about to cut through our belly. Cut through to youth remembered and lived.

That’s what you end up writing for the rest of your life. Those are the sparks setting the adult fire into perpetual stoking and waning.

Kim, his son, 37 years after his father guided me in Arizona, guides the Oregon audience through the shape of his father’s words and life as reconciling and reshaping youth:

For it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give–yes or no, or maybe–

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

Tucson –

William Stafford listens to us, his student hosts, Wildcats from Arizona who are let off the literary hook or leash through an act of professorial pronouncement – Go a little wild with him, but be aware Stafford, himself, can rattle sage poets and novelists who are your teachers, with his simplicity.

We newbies want our moment with the laureate, this National Book winner, this entrance into all things small and quiet but read by kings and laureates. That head strong inventiveness and our naiveté, he seems galvanized to, or at least that’s how youth remembers intersection with extraordinary literary fame and the passionate tribulations of angsty poet youngins.

The largeness of “the thing” at 19 – poets and revolution, the new coda of continental consciousness, and maybe an end to the old white man’s lament: immolation of the tweed, the pipe and patriarchal beard. We could cut it with machete, that potential paradigm shift, and the new horizons or hope for something different happening was exhilarating under a mescal moon. We were ready to rebuff it all, stoking bonfires as both homage to youth quaking the old and setting the world afire. Or at least that’s what we thought. Stafford speaks:

If you don’t know the kind of person I am

and I don’t know the kind of person you are

a pattern that others made may prevail in the worldand following the wrong god home we may miss our star.

For there is many a small betrayal in the mind,

a shrug that lets the fragile sequence break

sending with shouts the horrible errors of childhood

storming out to play through the broken dyke.

This time in my youth we are launching a new undergraduate literary magazine, Persona. We expect (want) validation, or vindication of a life young, but feeling heavy from the travails of a country left for old men and money seekers.

William Stafford takes an interest, understands the impatience of the unaccepted. He hears the clucking youth against the literary weight of teachers and national book award winners. It makes sense to him, that unchecked youth would want some small thing for us, fledglings, but big in our youth. Some time with him without the blustery literary devices of PhDs.

We watched him earlier in the day pushing the flow of that river he visited, pushing his hands into the riot of the hydro-ecology of a dry riverbed the afternoon before when he had arrived to Tucson, now a shadow of itself, furious with the glacial weight of melting snow and four days of rain.

Kim Stafford tells the Oregon audience his father always came to his hosts, wherever he was asked to be poet, with his hands cured by their river. He then flattened palms pointed to them as a form of supplication to the flow of life, river, what might also be benediction and genuflection. His dad would tell his new friends — poets one in all – the name of a river in a new country he was visiting. “You can never stand in the same river twice . . . .” Heraclitus seems to be stepping into the rivers of bold ink, into those currents where Stafford captures the light of a horizon flecked with stars and abiding rising sun. New horizons, old memories of youth.

Stafford names one of our Sonora rivers so his hosts recognize his awe of place and humbleness in the scheme of what this desert really means. He looks at my map and talks about the Santa Cruz River west of campus, reminding us that while a mostly dry wash year round, the shifting sands of Santa Cruz still echo the water coursing underground: the desiccant white-and-brown river sand hide life-affirming waters that pop up to surface some fifty miles down the line.

Stafford of Oregon is taken by the force of Sonora flash flood miles away uplifting the earth he stands on moments before his big reading on campus. El Rillito, this gaping riverbed north of town, he sees it’s flooding waters from hills and mountains and arroyos deeply etched in shadows miles away cresting fragile banks and eating away at a paved bicycle path.

He smiles.

We see it as the politics of bulldozers and cement hemming in wildness.

He studies each eddy, each roiling muddy pipeline, and sees a poem unfurling at pre-dawn. The hour of his poem building.

We try to talk about land speculators and ecology eaters stripping the desert valley.

He breathes in the swampy creosote bush aroma of wet desert and points to a swoop of buzzards lifting above the swells.

A smile. A dozen turkey buzzards, and that small crack of a smile.

There is a country to cross you will

find in the corner of your eye, in

the quick slip of your foot–air far

down, a snap that might have caught.

And maybe for you, for me, a high, passing

voice that finds its way by being

afraid. That country is there, for us,

carried as it is crossed. What you fear

will not go away: it will take you into

yourself and bless you and keep you.

That’s the world, and we all live there.

We drink impatience and tequila at noon, hold broiling debates over the melting facades of a country pushed into the harsh napalm glow of Vietnam, Cambodia, United Fruit, Dow, Nixon, all the reckless killing fields of corporations and manifest destiny. Whose land is this anyway, my Jew co-editor friend asks us. Was it Tohono or Mestiza . . . the battleground of interlopers with dollar signs etched in their souls? We want to prod the Kansas poet.

Stafford listens. Thinks. Speaks.

Once you cross a land like that

you own your face more: what the light

struck told a self; every rock

denied all the rest of the world.

We announce the underground railroad intersects right smack in our Old Pueblo, Tucson. The refugees filing into piping hot desert of organ pipe cactus, that matte black tongue of the Gila monster pointing toward El Norte, el paso del norte, or paseo del muerte – trail of death. We tell him they are searching for shelter in a new land, this new undeliverable homeland, which is the promise of the enemy’s financer accepting refugees.

He nods, gets it, knows what we know, and more.

The USA versus the world, versus the Salvadorans, anchored to the killing squads. Pushed out of highlands and crawling toward El Norte. We tell Stafford there’s some big news coming from the “big time” New York market, our sanctuary movement edited and packaged for TV: The blessings and underground work of men and women lifting the tortilla curtain, bearing witness and then sheltering the travelers at the risk of bolstering the very nature of what to the government is crime and to the human is care.

He knows, he says.

We roil at the incessant bombing of Nicaragua by Carter, the peanut farmer, Navy guy. We list the crimes of Chile, the crimes of C-Ch-CIA.

He listens.

We splatter paint on the commons when our apartheid village is ransacked by brutes in the ROTC squads, football walk-ons and the security patrols on our University of Arizona campus.

He watches.

William is there, listening, watching, at the edge of the crowd, talking to the uninitiated gawkers as we help protestors put back the South African shanty resurrected on our campus 9,000 miles from Mandela and Biko. Some of us are humbled by Stafford’s attentiveness, his inquiry into the Chicanos grappling with La Raza and a new canon for American Lit in a workshop he facilitates.

He listens and then reads dead poets.

He lifts a scoop of the Rillito River bed, remembers an earlier time years before when his Tucson hosts told the Kansas “Almost an Indian” (his childhood moniker) Stafford to come back in spring. “And here I am now, watching the waves of a desert awaken the water soul man inside a dust bowl rat who like me who flourishes in wet Oregon.” Listing, surfing saguaros, entire dumped cars barreling downstream, the desert jettisoning its skin some fifty miles away.

He observes . . . a poem inside.

The violence of flash flood and the hard ice melting high into the Santa Catalinas is the joy of Bill Stafford . . . . We know some turn of light or sound of red tail hawk will be lines for a future poem wired to his vast Kansas-Oregon synapses.

I will listen to what you say.

You and I can turn and look

at the silent river and wait. We know

the current is there, hidden; and there

are comings and goings from miles away

that hold the stillness exactly before us.

What the river says, that is what I say.

The audience is quiet, like Bill at first, his face reddened by traveling outside, like those of the foreigners’ when they see his hands open to them, this smallish poet crossing new open territory around the world. He talks of Afghanistan, Iran, and then a story of blinding snow where fence lines vanish and cows and cowpokes freeze like monuments of sacrifice with just the edge of bitterness in place to inscribe solitude into a story. Bill Stafford reads some lines from Wallace Stegner’s “Genesis: A Story from Wolf Willow,” calls it one of our country’s best, and then bows to read his own work:

The light along the hills in the morning

comes down slowly, naming the trees

white, then coasting the ground for stones to nominate.Notice what this poem is not doing.

He beckons us to hold steady the light in each morning alive, to listen to the air rustling with “small furry voles or moles . . . owls crunched up before gliding like gods for a talon swoop . . . crickets and their drumming… explosions of blossoms held in the darkness by croaking wet mating toads . . . .”

Or maybe that is a trick of youth, words recalled now at a distance. Re-appropriating, re-fabricating, retrofitting . . . . Something like what Stafford might have said: “This inching of truth away from a clear stratosphere. . . invention and imagination overcoming a poem . . . for a poem like memory is not a report on life but a painting, quiet but cinched to a fury and imagination.”

Maybe he said that, or maybe lichen-covered memory leads me away from the original source, one of Bill’s counterparts maybe, one that intersected with my youth – Galway Kinnell in El Paso, who knows. Or Bob Bly in Spokane? Garcia Marquez in Austin?

No matter how far he travels, the stints in Washington DC, or the road traversed and flights embarked upon, Stafford wants that West, the Willamette, the true angle of repose of sunlight falling onto the Pacific Northwest . . . . Where all hope is delivered to him in deciduous and pine forest gleaned by waterfalls, cataracts of tears. From an interview, Crazy Horse 7 (1971) by Dave Smith:

Smith: What do you see in your future?

Stafford: We’ll go back West and I’ll keep on writing poems. I keep following this sort of hidden river of my life, you know, whatever the topic or impulse which comes, I follow it along trustingly. And I don’t have any sense of its coming to a kind of crescendo, or of its petering out either. It is just going steadily along. So I inhale and exhale. I experience, write poems, get now and then, great feelings of being on the edge of writing something that reverberates through my own self and that’s very interesting.

White Sky –

They come to herald in their connection to Stafford, Oregonians looking to the past in order to re-jigger the waning future. Or, to imagine an Oregon of mythical proportions. Stafford serves as a light, a beam of tungsten into the cold gray of Willamette and Lake Oswego. There is a tender trailing of the voice in that aging, remembering hardscrabble histories.

Fewer birds lift. The mountain men of Stafford have given way decades ago to entrepreneurs, speculators, builders. These people in Tigard, maybe anywhere this year where Kim and others take the Stafford Road Show, are long in tooth, gray and easy to provoke with laughter, rhyme, words.

They are old but still children trapped, looking for a new way to capture their lives moving away from a horizon gushing with fecund life, the verdant buds withered, the trick of thinking like all the earth is inside your at those tender ages of 10 or 12 now snores in a chair.

Somewhere in that slipstream, even back to Tucson, or when we met in El Paso, or was that place in San Antonio or Austin, Stafford rose up, listened and then spoke words of youth, the measure of things. He never wanted a muse, really, tapping away on his shoulder delivering what and how to say it.

I glanced at her and took my glasses

off–they were still singing. They buzzed

like a locust on the coffee table and then

ceased. Her voice belled forth, and the

sunlight bent. I felt the ceiling arch, and

knew that nails up there took a new grip

on whatever they touched. “I am your own

way of looking at things,” she said. “When

you allow me to live with you, every

glance at the world around you will be

a sort of salvation.” And I took her hand.

The poet’s poet son makes sure to jostle with that muse-concept, makes sure that people he meets and will meet on this Oregon Trail of 100 Years after His Birth do not look for a magical essence for being alive as artists, writers. He knows the routine of a father who penned 20,000 poems, daily exercises like a Zen master waiting for the grasshopper to light on water, or the master pushing hands until mountains move.

Get on with the exercise of writing, maybe that’s the coda I learned at age 19 from Bill. Just go out into the world and write it. The déjà vu of meeting him twice, or three times. That universal, the harmony of youth always jostling with one’s old fellow. Those stories and memories are the best, for sure, and Bill Stafford ramified that 37 or 40 years ago, or the last time when he was on the Palouse, when I met him, listening. Or was that Galway?

His son recalls things that never happened that are, and things that happened that will never be the inseam of a persona, nothing that will shed into a character revealed, but still, the things that matter, they haven’t happened yet. That is the poem of green earth and white sky:

The post Sky Islands: Jaguars, Apaches, Spirits, and the “Last” Emblem of a Dying Interloper Colonializing Genocidal Race first appeared on Dissident Voice.Many things in the world have

already happened. You can

go back and tell about them.

They are part of what we

own as we speed along

through the white sky.But many things in the world

haven’t yet happened

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.