Sanah Baig, who has years of experience working for the US government, explains why she chose to join the Plant Based Foods Institute, and her thoughts on the MAHA and livestock lobby.

Few people know about agricultural policy in the US as well as Sanah Baig.

She spent years working for the government, beginning with a stint at President Barack Obama’s US Department of Agriculture (USDA) between 2011 and 2016, before returning to the agency under Joe Biden’s administration in 2022. During this time, Baig also served as a senior policy advisor for agriculture and nutrition to the White House.

She left the government this January at the end of the Democrats’ term, and five months later, joined the Plant Based Foods Institute (PBFI) as its new executive director.

Her tenure has dovetailed with the chaos that has come with Donald Trump’s second presidency. The administration has erased any mentions of climate change from the USDA website, reduced funding for the food stamps programme by around 20% (the largest reduction in its history), and scrapped the annual food security survey to stave off criticism of the budget cuts.

With a few months under her belt at PBFI, Baig speaks to Green Queen in an extensive interview about her role, the government’s view on plant-based eating, the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) movement, the influence of meat lobby groups, and the proposed changes to the national dietary guidelines.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Green Queen: What compelled you to join PBFI? What has your focus been for the first few months?

Sanah Baig: I was drawn to PBFI’s mission to architect a food system where plants take centre stage, meaning food is produced using dramatically fewer resources and less land, farmers and rural communities thrive through new market opportunities, and families have delicious options that nourish and delight them.

I saw an opportunity to link actors across the food value chain, from researchers to companies to consumers, as well as to partner with unconventional allies like economic development and public health groups.

Since my career has been focused on agricultural development, I bring a natural passion for working with producers, the research and extension communities, government officials and industry to scale innovative food systems. To that end, we’ve just secured philanthropic funding to advance our domestic sourcing and upstream value chain development work.

Since starting as executive director in June, I’ve been focused on ensuring PBFI can maximise its unique role as the sister organisation to the Plant Based Foods Association, and fill gaps in a robust NGO ecosystem that has made huge strides to increase R&D funding, public procurement policies, institutional foodservice adoption, and menu and behavioural change efforts that advance plant-based foods.

In the coming months, we’re launching a new effort that will build regional plant-based agricultural networks, starting in the Midwest. We’re also in the process of building out our team and developing strategic workgroups that will tackle key challenges around plant protein production, market development, and consumer education.

GQ: What are the biggest challenges facing you in your new role? What are your goals going forward?

SB: The exciting challenge is to come in as PBFI’s first executive director and translate the strong foundation of impressive knowledge, research, and relationships into action. That means new programmes that build upon our learnings, including from our signature domestic sourcing initiative, which connects plant-based food companies with American farmers to build resilient domestic supply chains.

The level of interest in the organisation these first few months has been extraordinary – we received 1,000+ applications for two new positions, which tells me there’s significant buy-in for this work and recognition that plant-based foods are a critical piece of the giant food systems transformation puzzle.

We also just secured two new grants to support our domestic value chain development efforts and to strengthen the Plant Based Foods Global Alliance, which will enhance collaboration across emerging markets like Turkey and Argentina, and more established markets like Canada and the EU.

As the global market for plant-based foods continues to grow, so do our shared challenges, especially in terms of labelling, infrastructure, and positioning. Especially against the backdrop of a polarised world, with food issues in the crosshairs, maintaining clarity and progress requires ecosystem-level coordination.

We face uphill challenges around shifting both agricultural incentives and narratives. On the incentive side, we need to create pathways for farmers to grow more diversified inputs like oats, peas, chickpeas, small grains and a range of emerging crops with functional and nutritional benefits that meet consumers’ needs.

We need to ensure they have the agronomic support, insurance coverage, infrastructure support, market connections, and long-term contracts to sustain economic viability. Farmers need to know the demand is there. This requires working with governments at all levels, research institutions, and the private sector. This is not a domestic issue, but a global one. The new Eat-Lancet report notes that we must increase the production of fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts by 9% annually, and up to 150% by 2050.

On the narrative side, we’re working to reframe how people think about plant-based foods. Mindset shifts are not easy, and incredibly context-dependent. But we see an opportunity to tell a better story about plant-based foods that highlight choice, abundance, deliciousness, wellness, and local tradition.

In the policy space, we can strengthen our message about rural opportunity, public health improvement, and climate resilience as our evidence grows. My main goals are to build the partnerships, programmes, and policy frameworks that make this vision a reality – connecting farmers to markets, advancing the research agenda, and creating spaces for collaborative problem-solving across the entire value chain.

GQ: As a political insider, how do you think government agencies like the USDA view plant-based eating?

SB: Nearly two decades ago, I got an internship at the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service HQ. That experience lit a fire in my belly because it introduced me to a set of wickedly complex challenges around food production, not just in the faraway places I focused on as an international relations student, but right here at home.

It was astounding to see how much public R&D and global cooperation were required to produce safe, nourishing, affordable food with fewer resources, booming population growth, and new pests and diseases constantly emerging. I knew these problems were not just worth solving, but absolutely existential. At such a formative stage, it was deeply motivating to be surrounded by the world’s foremost agricultural scientists working to stay ahead of these crises.

It also opened my eyes to the realisation that government agencies are not monolithic entities with single viewpoints. The USDA alone is made up of nearly 30 distinct agencies and offices with differing missions (for example, resource conservation, rural development, forest management, food safety, innovation, and foreign trade).

And it depends greatly on the leadership at the top. We had a saying that “people are policy”, which I saw firsthand at both the USDA and the White House. It’s more apparent than ever in today’s political reality.

During this time, I had a growing interest in nutrition as a widening circle of family members began suffering from diet-related chronic diseases. In a different corner of the USDA, the latest Dietary Guidelines for Americans were developed and I read it closely. Even then, the 2005 report underscored the crucial role of vegetables, fruits, whole grains and legumes as foundational to our health.

When I looked at the USDA’s research, marketing, and farm production programs, I was shocked that these programs did not focus on incentivising the very foods that the department itself said were most beneficial for us. I set out on a mission to understand why, and to do my best to close the gap. Ultimately, it depends on the agency’s mission, what its leadership prioritises, and what resources are available.

Throughout my decade in government, I was pleasantly surprised to see interest in plant-based foods from different angles. The science community especially understood that meeting global demand for protein by 2050 was not possible within the current system and that we needed to embrace innovation to fill the growing supply gap.

The USDA allocated at least $30M for plant protein R&D in just the past few years, with much of the innovation driven through interest by land grant university partners who recognised the need for US competitiveness. This was complemented by historic investments in the USDA’s Specialty Crop Block Grant Program supporting state-level fruit, vegetable, and nut production.

The Food is Medicine movement championed by the HHS embraced plant-forward eating through produce prescriptions and medically-tailored meals. NIH Research Grants funded clinical trials on plant-based diets for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and inflammation.

The Department of Defense piloted plant-based MREs (Meals, Ready-to-Eat) in collaboration with private suppliers. Small Business Innovation Research Grants via the USDA, the National Science Foundation, and the Department of Education fund plant-based protein startups.

To me, these are clear signs of progress that policy officials acted on the overwhelming body of evidence that plant-based foods advance human and planetary health, and expand economic opportunity. That said, progress is not linear, and we have to work harder than ever to sustain these efforts, especially with hundreds of thousands of federal workers exiting government service this year alone.

GQ: How do you view the rise of meat and dairy consumption in the US, and animal protein’s winning role in the culture wars, especially in the context of your role and goals at PBFI?

SB: Looking at the data, meat and dairy consumption has seen a steady long-term rise, and this is happening against a backdrop where the median US farm-only income was negative $900 in 2023. This indicates the current agricultural system isn’t working for many producers, regardless of long-standing cultural narratives around it.

PBFI is working to offer an on-ramp for producers to get to true profitability and stability through the production of crops needed for a growing global plant-based market, especially in alignment with the Planetary Health Diet. Whether it’s growing beans, mushrooms, or almonds, there’s real economic potential here that spans both whole and value-added foods.

And it’s not an all-or-nothing approach; we’re seeing corn growers adding legumes into their rotations for nitrogen-fixing, soil health and yield benefits. I’m excited to work with commodity producers to see how they can integrate new crops into their systems and generate more economic and environmental value.

As for the culture war aspect, there’s a really compelling and untapped story about the power of plants. The plant-based movement is about abundance, choice, opportunity, and tradition. Plants have been at the centre of human diets and agricultural traditions for millennia.

The more we can celebrate the deliciousness, versatility, and nutritional benefits of plant-based foods, and connect that to the economic opportunities for growers and rural communities, the more we can move beyond divisive rhetoric and toward practical solutions that benefit everyone.

GQ: What are your thoughts on the proposed US dietary guidelines? Do you believe the recommendation to increase plant protein intake and reduce red meat will make it to the final document?

SB: I am hopeful that the final report will reflect the recommendations from the Advisory Committee’s scientific report issued late last year. The committee proposed emphasising beans, peas, and lentils and moving them to the top of the “protein foods” subgroup.

One of our main goals is to ensure the revised US dietary guidelines recognise the nutritional benefits of plant-based foods and diets. They provide the basis of many federal food procurement programmes, including nutritional assistance programs, and are a pathway to ensure increased access to plant-based options that many rely on to meet specific dietary needs and preferences.

GQ: Do you believe government bodies and public policy are under the influence of the livestock lobby to some extent, as several investigations have claimed?

SB: Policymakers respond to the groups that engage them most. As public servants, their job is to seek input and feedback when advancing new programs, policies or laws.

Groups that represent conventional agricultural producers have a long history of advocating for their interests at both the national and federal levels. For example, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association was founded in 1898, which means they have had a more than 125-year history of building relationships with public officials. They formed because of clear challenges they were facing, like a monopoly in the packer market. And they understood the power of collective action at the national level.

Fast-forward to 1985, and groups like the Organic Trade Association emerged with their own set of clearly defined goals around creating uniform standards, certification, and marketing programs. In five years, they and a coalition of like-minded groups pushed forward the passage of the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990 to directly address those needs. We should learn from those lessons.

There has never been a larger coalition of organisations calling for plant-forward food systems. But this ecosystem is still in its emergent stage. We must urgently align on our core goals in order to present unified asks to policymakers.

As the trade group representing US companies that make plant-based foods, PBFA has been advocating on behalf of the industry for a fair and transparent playing field for many years. PBFI is focused on welcoming US farmers into the supply chain to catalyse more domestic production, and unlocking policy incentives to make this feasible.

But we can’t do it alone, and I’m excited to have so many allies working together to set a clear policy agenda that we can unite around.

GQ: What opportunities and challenges do you see with the MAHA movement? Do you see a chance to align on certain issues?

SB: There is common ground in wanting to do everything we can to make healthy foods more affordable, more accessible, and more delicious than junk foods as a way to combat chronic diet-related diseases.

The delicious part is getting better: plant-based innovation has come so far in terms of taste and variety. Accessibility is advancing through foodservice, especially getting nutritious plant-based options into schools, hospitals, workplaces, and communities that want and need options that align with their dietary needs and preferences.

Part of the affordability challenge goes back to the farm level, and this is where the opportunity gets really interesting. The majority of what we grow in this country does not go to feeding people directly.

If we can begin to change the upstream supply chain by incentivising farmers to grow more diverse crops for direct human consumption, including the ingredients needed for plant-based foods, we can improve the downstream cost for consumers.

Of course, there’s a lot of creativity needed in the middle of the supply chain, too. Plant-based foods span an incredible spectrum, from whole grains and legumes to innovative products. Our focus should be on supporting farmers, advancing research, improving nutrition access, and giving consumers better choices that fit their budget.

These are goals that can resonate across many different political perspectives and seek to unite us around what to advance, versus solely on what to ban.

GQ: Do you believe more Americans can, after all, become flexitarians or meat reducers?

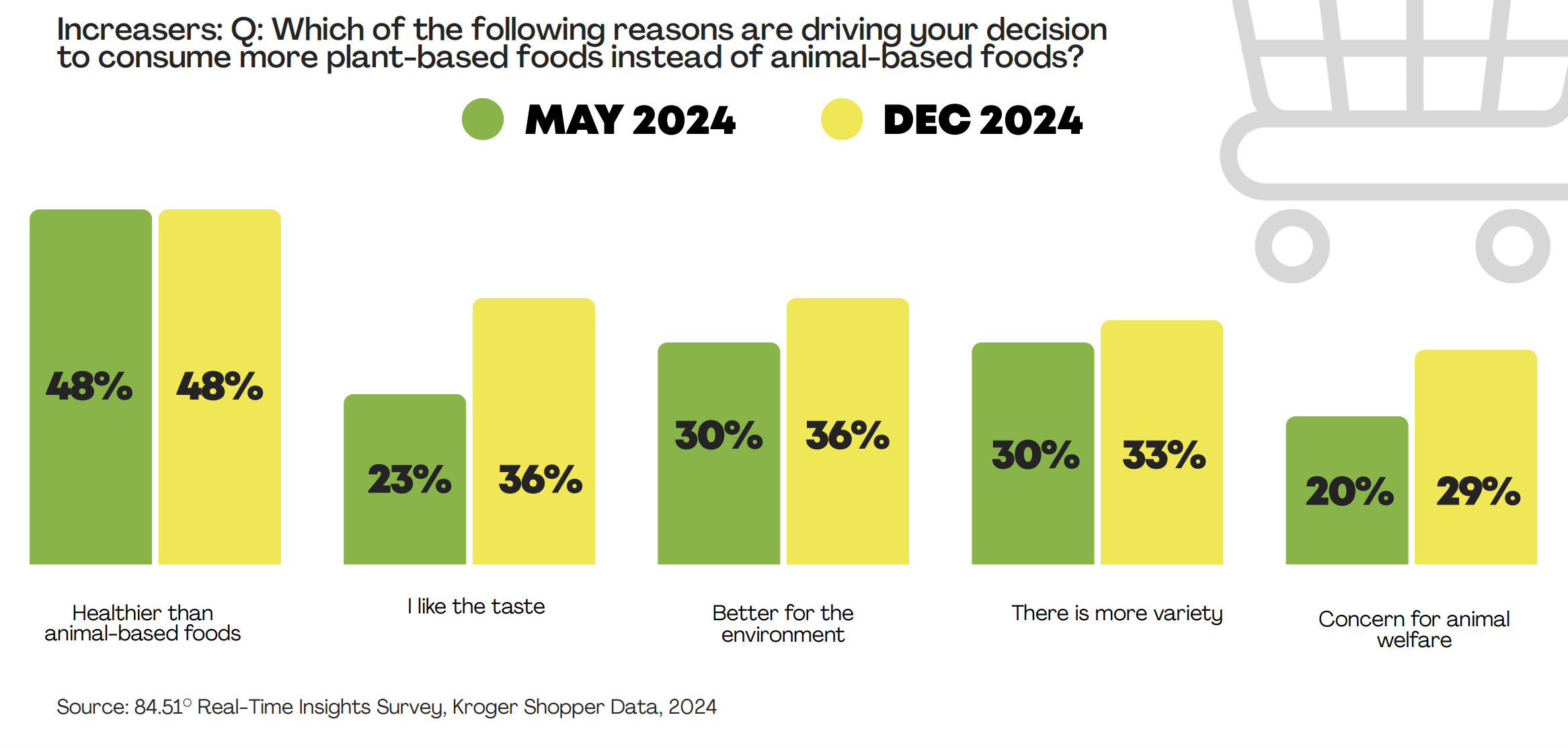

SB: Absolutely. We know from our research that 59% of US households purchase plant-based products, and 79% of those households are repeat buyers. At the same time, taste concerns (historically the biggest barrier) have dropped significantly, from 41% in 2023 to just 27% this year.

There is a big opportunity gap in access. People may be willing and interested in plant-based foods, but it’s not always easy to find the options that align with their needs/preferences in retail or foodservice settings.

Our research indicates plant-based options are still hard to find, and variety doesn’t always align with growing interest areas – for example, culturally diverse flavors or cleaner labels. Our role is to be the convener and catalyst, bringing together stakeholders across the entire value chain to identify barriers and co-create solutions.

We’ll work with farmers to diversify into plant-based ingredient crops, support manufacturers in scaling innovation (and we’ve already seen rapid progress), partner with retailers and foodservice operators on accessibility, and connect into the research community advancing ingredient science and consumer insights.

When these value chain partners are aligned and supported, flexitarian eating becomes an easier choice. It’s not about convincing people to change; it’s about building a system that makes it easy for them to put more plants on the table.

GQ: What’s your take on the ultra-processed foods (UPF) discourse and its impact on both the animal protein and plant-based industries?

SB: Overall, the UPF discourse is driven by the good/correct desire to improve diet quality and public health outcomes in America and beyond. The public and decision-makers alike have coalesced around the term ‘ultra-processed’ as shorthand for foods that shouldn’t be consumed.

But the idea that a food is unhealthy or unsustainable just because it is processed lacks scientific backing and confuses consumers. To lead to the positive public health outcomes we all desire, UPF policies should target foods that do not provide positive contributions to the diet – that is, true junk foods – and not lump in nutrient-dense foods like plant-based meat, dairy, and eggs. That is to say, the focus should be on championing nutrition, not punishing processing.

Thankfully, health organisations, including the American Heart Association, are also calling for nuance in the UPF space and recognising that plant-based products contribute positively to healthy dietary patterns.

We are hard at work to prevent nutritious plant-based foods from being lumped into state and federal definitions of UPFs and to ensure that consumers who rely on these products to get the nutrition that they need will continue to have access to them.

GQ: What has the plant-based sector done wrong over the last five years? What’s it gotten right?

SB: As an ecosystem, we can tell a better story and challenge oversimplified narratives, especially about overall VC funding or one company’s sales being the only measures of success. We can embrace both whole foods and value-added products as part of a diversity of options available to consumers.

Beyond the bright spots in foodservice, things are steady and improving in some dimensions of retail, despite narrative challenges. Plant-based sales have stayed steady or grown in many pockets (milk, protein powders, and tofu) and in terms of household penetration and repeat purchases.

Visibility and proper merchandising matter: plant-based doubles its share in e-commerce (6% of sales) versus in-store (3% of sales). Based on 2024 migration analyses from Kroger’s 84.51 data arm, we are seeing that consumers are growing happier with the taste and texture of plant-based products.

Manufacturers are innovating on the R&D side. Consumers are noticing and responding positively, but they want more. Specifically, more variety, better prices, and convenient formats.

I think it’s most productive to focus on lessons learned throughout the evolution of this relatively new sector. Innovation has been our greatest strength. Plant-based manufacturers have pushed R&D at a pace rarely seen in the food sector, responding to consumer insights in real time.

The results are promising: taste and texture are no longer the barriers they once were, and more consumers are choosing plant-based options. This is underpinned by agility: when consumers ask for cleaner labels, higher protein, or ingredients sourced through regenerative practices, plant-based companies have been able to pivot more quickly.

In a world where consumer preferences are shifting rapidly, this responsiveness is a powerful differentiator.

The post How A Former USDA Stalwart & White House Advisor is Leading the Plant-Based Fight appeared first on Green Queen.

This post was originally published on Green Queen.