The EU is losing out to other regions on the biotechnology front, thanks to an outdated novel food framework. A regulatory sandbox could reinstate its leadership.

Europe is home to some of the world’s most avant-garde food tech startups. So why do they end up leaving?

The problem, according to a new report by think tank the Ministry of Future Affairs, lies with the EU’s outdated system to assess the safety of new products before they can launch into the market.

The bloc’s novel food regulatory framework is competitive with others in terms of the timeline and robustness. However, the length of assessments is twice as long as promised, raising costs for startups and driving away investors from the region.

These regulatory inefficiencies have put Europe’s position as a biotech leader “under threat”, harming its strategic autonomy and food security. For instance, companies like Onego Bio (which makes fermentation-derived egg proteins) and cultivated meat player Meatable have chosen to apply for approval in the US or Singapore first, respectively, where the framework is clearer and timelines shorter.

The startups that opted to file novel food dossiers in Europe first, like Finland’s Solar Foods, say the move has “come at a significant cost”.

“Our regulatory journey has taken more than twice as long as the EU’s own market approval timeline anticipates. In the meantime, we’ve had to enter other global markets just to remain viable while waiting for approval at home,” says Juha-Pekka Pitkänen, co-founder and CSO of the Solein protein maker.

“We’re not asking for lower food safety standards, but for a regulatory process in our home market that is efficient, predictable, and enables innovation to thrive,” he adds.

In response, the Ministry of Future Affairs has convened food safety, regulatory, and legal experts, who analysed regulatory pain points experienced by applicants and have formed a Framework for a Pan-European Regulatory Sandbox for Novel Foods.

“We fund innovative European food scientists and entrepreneurs, only to see them leave for other markets due to the EU’s unpredictable regulatory approval process. This further strengthens the geopolitical power and competitiveness of other countries, such as China, which benefit from the lack of an efficient regulatory pathway to market in Europe,” says Anna Handschuh, the organisation’s managing director.

“Member states that wish to support and benefit from the growing food biomanufacturing market should collaborate on setting up regulatory sandboxes.”

What’s wrong with the EU’s novel food framework?

The report, titled Closing the Food Innovation Gap, suggests that though the EU’s novel food regulation is often seen as a barrier, it does offer some unique benefits.

For instance, it covers a wide range of technologies, including cell cultivation and precision fermentation, and follows a centralised procedure – once approved, companies can sell in all 27 member states. Applicants can also require five years of protection for the data they’ve generated during the period they are putting their dossiers together, as well as confidential treatment of certain information.

Plus, once approved, the decision is valid indefinitely, meaning that companies don’t have to go through any renewal process (unlike feed additives and smoke flavourings).

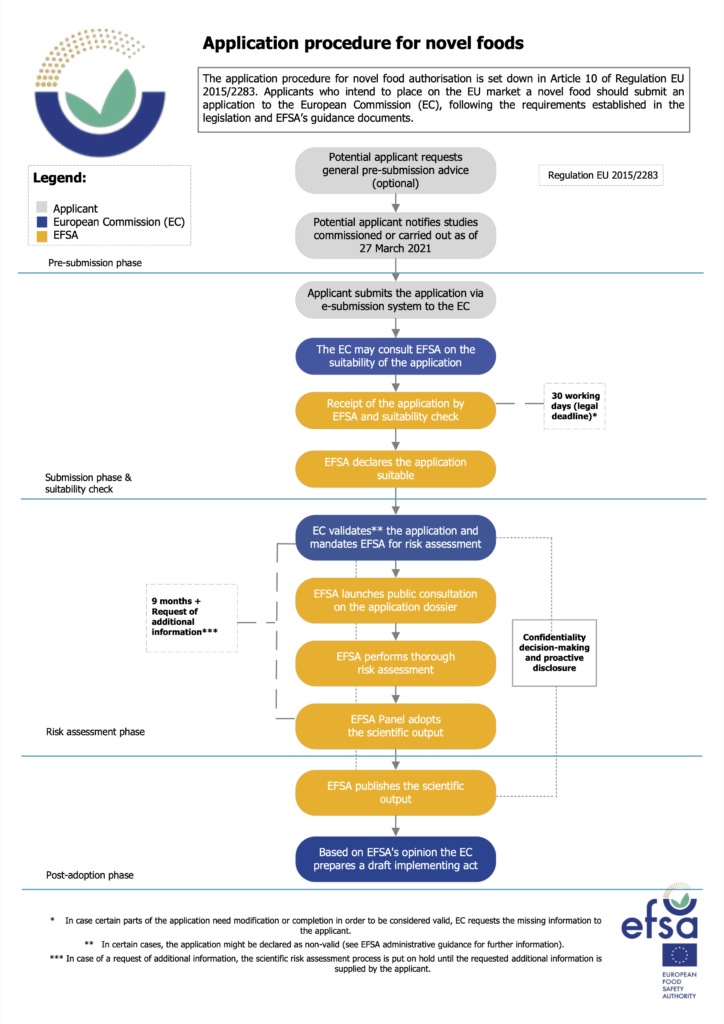

To get the green light, applicants generate data and gather studies to support their dossiers, which are then validated by the European Commission, before being passed on to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) to perform a suitability check (which takes 30 days).

The EFSA then performs a scientific risk assessment before publishing its opinion, a process that can take nine months (and can be extended if the agency wants more information). Based on this opinion, the EU Commission prepares a draft implementing regulation, which 55% of member states (representing 65% of the bloc’s population) must approve. The legal timeline for this process is seven months.

In actuality, the average time it takes for a novel food product to be approved in the EU currently is 30 months, far higher than the stipulated 18-month timeline – and this can stretch to as long as five years. In comparison, average timelines in Singapore, Australia and New Zealand are 12 to 24 months.

“The costs of generating data to support a novel food application in the EU are higher, and there is more uncertainty due to the cost of additional data requests that occur during the risk-assessment period,” the report suggests.

Indeed, a novel food dossier in the EU could set a company back €250,000, on par with Australia and New Zealand, though far higher than the €100,000 expected in Singapore and €75,000 needed for a self-affirmed GRAS determination in the US.

This is because the EFSA requires data from at least five independent batches of the novel food ingredient, whereas the other regions require a minimum of three. The EU regulator further asks for data on shelf life and stability in relevant food matrices, adding extra costs and complexity.

How a regulatory sandbox can break the EU’s innovation deadlock

The Ministry of Future Affairs suggests that food tech investors have been recommending European companies to launch in the US, and have deprioritised the EU as an investment destination. Its solution to this situation is inspired by a former EU member state.

In March, the UK opened a regulatory sandbox for cultivated meat, connecting eight startups (three of which are from the EU) with scientists, regulatory experts, and academic bodies to overhaul the regulatory framework and fast-track their path to market.

This enables British regulators to “generate the information needed to answer outstanding questions and increase the efficiency of the regulatory process”, without compromising on existing food standards, according to the sandbox’s head, Joshua Ravenhill. “Sandboxes like ours facilitate innovation whilst ensuring citizens’ safety,” he said.

Sandboxes are time-bound regulatory environments in which innovative products can be tested under supervision, and often with temporary exemptions from standard rules. The report outlines that they can streamline approvals, reduce costs, shorten timelines and remove administrative burdens.

Through its pan-European sandbox framework, the Ministry of Food Affairs aims to inspire a transparent pre-market approval process, create high-quality dossiers that demystify requirements, streamline and fast-track procedures, foster cross-border collaborations, and restore investor trust.

Aside from the regulatory testbed, its framework proposes a Living Lab to host public tastings of novel foods, an experimental regulatory learning space to reduce fragmentation across borders, and shared AI and digital tools to improve efficiency.

This sandbox would last for 2.5 years and comprise 10 food tech companies planning to file a dossier in the next 12 months, with the key result being the submission of at least two applications by the end.

“The framework aims to transform the regulatory process from what is currently viewed as a barrier into a strategic enabler. With the process laid out, we aim to demonstrate that novel foods approval can be completed within the regulated timeline while upholding safety,” notes Hannah Lester, CEO of Atova Regulatory Consulting.

Fortunately for the alternative protein industry, the EU has shown it is willing to modernise its novel food framework. Its new life sciences strategy will introduce the Biotech Act next year, which aims to speed up approvals for these innovations by mobilising investments and creating an AI-led supportive tool. In addition, the EU Parliament has recommended the use of sandboxes to assess applications, while helping companies transition from this testbed regime to full market access.

The post Experts Propose Plan to Create EU-Wide Regulatory Sandbox for Novel Foods appeared first on Green Queen.

This post was originally published on Green Queen.