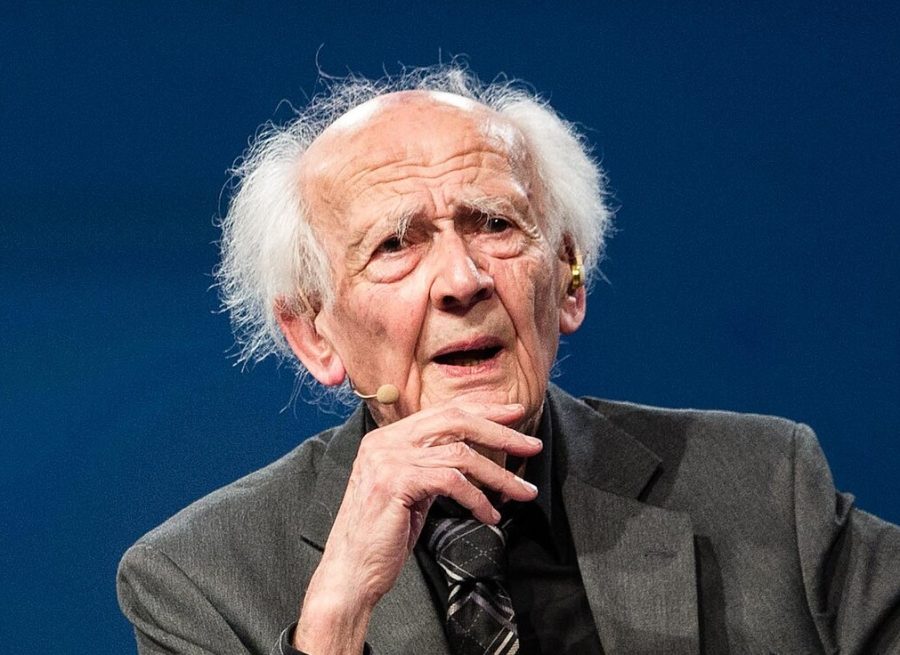

Polish-British sociologist Zygmunt Bauman was born 100 years ago today. He is best known as the theorist of “liquid modernity,” in which social bonds decline in favor of an atomized individualism.

Zygmunt Bauman is globally recognized as a theorist of “liquid modernity.” The term, which suggests that the main feature of the current stage of the modern era is increasing individual and collective uncertainty, gained widespread popularity due to his book of the same title published in 2000. Few remember that he began his academic career much more humbly as a researcher studying the British labor movement.

At the turn of the 1950s, in the early years of the Polish People’s Republic, universities became the target of a government campaign to establish Marxism-Leninism, the Eastern Bloc’s official ideology, as the hegemonic approach in higher education and research. Sociology was condemned as a “bourgeois” discipline. Following the principle of partisanship in philosophy, all higher learning was required to support the existing political order.

Navigating this highly restricted academic landscape became the defining experience for a generation of Polish intellectuals. Bauman was no exception. He was trained as an adversary of Western social scientists, exposing how their work did not conform to Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy. His formation took place on the front lines of the ideological Cold War.

It was not long until it became clear that this ideological method of scholarly inquiry revealed more about its own shortcomings than the errors of its presumed opponents. One of the things that disturbed Bauman in Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy was the complete absence of society from the worldview of a nominally socialist state.

The official scholarship maintained that the “masses” must follow the direction decided by the communist party leadership. There was no need to consult the public on political decisions; as long as its passivity was secured, a bright communist future would follow.

In contrast, Bauman believed that no progressive change could ever succeed without simultaneously fostering the autonomy and agency of the people. This political stance was inspired by his research; in his view, the primary reason behind the historical success of the labor movement in Britain was its ability to mobilize a broad coalition of diverse social forces. Accordingly, by sidelining their democratic promises, the communist leaderships of Eastern Europe doomed themselves to mounting political and intellectual stagnation.

Their later fall proved many of his predictions prophetic. Bauman’s early interest in social movements was, therefore, an act of defiance against a detached and self-referential ideology that refused to acknowledge its flaws.

Ultimately, this critical attitude would lead him to be branded as a “revisionist” and exiled from his native Poland. But even on the other side of Cold War borders, Bauman continued to be an outsider. Unlike many of his fellow émigrés, experiencing the violence, antisemitism, and hopelessness of the Polish communist regime reinforced his conviction that even atrocities deserved serious structural examination.

Bauman acknowledged that Vladimir Lenin’s version of socialism turned out to be a “death sentence on human freedom.” Yet admitting this was different from ignoring the historical motives behind the emergence of radical ideas and movements. Perhaps partially due to his formation, he understood that anti-communism was never only about opposition to the Eastern Bloc.

For Bauman, sociology was a political choice. Rather than conforming to the intellectual orthodoxies of his time, he sought to expose how these orthodoxies failed to capture modern reality. Such was the result of his dramatic biography but also his conscious decision to remain a critical scholar. The combination of his refusal to accept the existing consensus and curiosity about contemporary human experience became a permanent feature of his thinking, contributing to much of the originality of his later work.

Searching for an Alternative

Although Bauman welcomed the end of the Cold War, he did not share widespread optimism at the turn of the new millennium. The communist project, in his view, was integral to what he called the “solid” phase of modernity, in which achieving collective improvement was synonymous with preserving social stability. Its fall represented not merely the failure of a political idea but also the end of a world that sought safety, certainty, and rationality for all. The crisis of socialism was also a crisis of modernity, and its consequences reached far beyond the newly post-communist Eastern Europe.

According to Bauman, modernity’s new, “liquid” phase displaced these earlier promises. In the place of prior rigidness, individuals have now become able to freely pursue their identities and aspirations. Bauman acknowledged that this was not a one-sided phenomenon: seeing as the promises of “solid” modernity had often assumed oppressive forms, its new phase offered previously unknown freedom from traditional social norms and constraints. At the same time, it also generated unprecedented instability, which ultimately aggravated the injustices known from the previous centuries.

Rather than focusing exclusively on the hopes or anxieties of the new historical episode, Bauman found a way to reconcile the two — admitting the uniqueness of the post–Cold War period while exposing its most striking contradictions.

It is often said that much of Bauman’s late writing revolved around the recurring themes of modernity, globalization, consumerism, and uncertainty. One can debate to what extent this kind of sociology has withstood the test of time. Although his ambition to capture social reality in its entirety captivated readers, it equally antagonized most fellow academics and social scientists. Neither a philosopher nor a historian, he continued to dialogue with theorists across the ages, refusing to conform to the language of his own discipline.

At the same time, like few other academic authors, Bauman knew how to relate to the everyday experiences of living in “postmodern” society. The issues he raised, such as growing insecurity and loneliness, resonated with thousands of readers around the world. His social theorizing was characterized by an unwavering belief that conscious collective participation in culture and politics is indispensable to creating a better society.

This democratic commitment was a crucial factor behind the international success of his books. As Bauman’s biographer Izabela Wagner argues, abandoning the rigid academic style was a conscious decision to reach a broad, global audience. Drafting policy proposals was never Bauman’s intention. But narratives on historical change also have their consequences.

What made the “liquid modernity” thesis so compelling was the acuteness with which it captured the contradictions of nascent neoliberalism. Bauman’s books consistently avoided the term “neoliberalism”; and yet, his significance as a thinker is inseparable from it.

At a time of heightened faith in liberal globalization and free-market capitalism, Bauman offered a powerful rebuttal to what he viewed as the central promise of “liquid modern” times: that individual solutions can resolve socially generated problems. He reminded us that the loss of social bonds cannot be compensated for by market mechanisms — and that any political worldview which ignores the agency of society is doomed to failure.

Faced with a hegemonic ideology claiming that “there is no alternative,” Bauman once again took the role of a dissident, critically examining the prevailing intellectual fashions of his time. The sudden success of his books in the 1990s and 2000s proves that there was a need for such a left-leaning, socialist-inspired perspective. One of Bauman’s enduring legacies, therefore, is to offer us an alternative to thinking about the current historical episode beyond liberal narratives about the “end of history.”

No Democracy Without the People

Life provided Bauman with ample reasons to fear abuse from others. In 1939, at age thirteen, he witnessed the Nazi-German invasion of Poland. His world collapsed again in 1968, when he became a victim of an antisemitic purge and was exiled by the Polish communist regime. No one understood better than Bauman the tangible possibility of political catastrophe. And yet, he did not allow it to shatter his belief in democracy and in the people that create it.

In one of his final articles, Bauman offered what could be called a warning against “populism,” or at least the shortcuts proposed by aspiring “strongmen and strongwomen” of contemporary politics. At the same time, he admitted that support for their fraudulent proposals is a result not of erroneous ideas or deception, but a genuine loss of safety and control felt by a growing number of people across the world. Ignoring this reality was a sign of political and intellectual stagnation, of a kind that Bauman had witnessed before.

Condemning “populism” without recognizing the growing powerlessness of democratic politics was no solution. If anything, Bauman saw all narratives about “mistakes and deformations” of otherwise flawless political orders as a source of false comfort, distracting us from tackling the roots of real problems.

A defining feature of Bauman’s thought was the conviction that it was not history, elites, or markets but the people themselves who ultimately decide the course of change. For this reason, despite witnessing some of the darkest chapters of the twentieth century, he never lost faith in the democratic idea. He was a thinker of his time: ever curious about the evolving human experience, hoping to make it better for others than it had been for him.

One hundred years after his birth, Zygmunt Bauman reminds us that the only way to prevent the past from repeating itself is by improving the present — and that the future is only ours to make.

This post was originally published on Jacobin.