On the first day of this year’s United Nations climate summit, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva promised attendees that this conference would be different. The 30th annual Conference of the Parties, or COP30, would be the “COP of truth,” he said.

The Brazilian president’s forceful remarks at the outset of negotiations in the Amazonian city of Belém were meant to set the stage for a new chapter in international climate diplomacy. On the 10th anniversary of the Paris Agreement, the time had come, according to Lula, to stop arguing about what the historic agreement requires and instead focus on implementation — actually taking the steps required to both reduce greenhouse gas emissions and protect countries against the coming economic and public health consequences wrought by climate change.

In the same speech, Lula called for a “road map” for the world’s phaseout of fossil fuels. This was intended to make good on an international agreement made two years ago at COP28, when U.N. member countries reached consensus on the need to “transition away” from coal, oil, and gas. The so-called UAE consensus, named for the host country of that year’s conference, marked the first time a blanket transition away from fossil fuels was ever officially mentioned in the Paris Agreement framework.

But the Brazilian delegation, which was responsible for overseeing COP30 negotiations and ultimately brokering a new deal, was confronted by a different truth than the president envisioned. The viability of the planet may come down to a few degrees Celsius of warming, but in Belém’s fluorescently-lit negotiating rooms, everything ultimately came down to dollars and cents.

In the end, it may well have been a more honest COP than those that preceded it — just not in the way President Lula intended.

The most substantial new agreement negotiated at the conference reflected this realism. The delegations agreed that, by 2035, the world would triple international funding provided to help developing nations adapt to the consequences of a warmer world.

To many, however, the list of missed opportunities spoke louder than the victory on climate adaptation. Brazil’s proposed “road map” did not make the official ledger. Indeed, there were no new agreements to wind down fossil fuel use or curb deforestation. The latter omission appeared to be either an intentional accident or a diplomatic blunder: The COP presidency had put the new, controversial language on fossil fuels in the same sentence as the comparatively benign clause on halting deforestation, dooming it by association.

The Paris Agreement’s temperature targets, which aim to keep global warming “well below” 2 degrees Celsius and ideally below 1.5 degrees C over preindustrial levels, remain as abstract as ever after COP30. A detailed plan to help nations meet emissions reductions goals that would comply with the Paris Agreement was axed from the final decision.

Just before the conference began, the U.N. put out its annual “emissions gap” report, which found that the world is on track for warming of between 2.3 and 2.8 degrees C this century. The agreement made in Belém seems unlikely to change that math. Ten years after the Paris Agreement, its champions still have not found a way to get the world to live up to the landmark deal’s most famous goals.

This year’s summit took place at the edge of the Amazon, a symbolic decision meant to uplift the rainforest and the Indigenous peoples who live in it. Though the conference was rocked by protests and demands for greater Indigenous participation and protections, a collegial air took root among the official negotiators for the first half of the two-week conference. With U.S. President Donald Trump thumbing his nose at the proceedings by refusing to send an official delegation, other world leaders were keen to prove that international progress on climate change could continue in the absence of American cooperation.

Prior to Lula’s statements at the beginning of the negotiations, the expectation was that the discussions would largely focus on finding a path toward reducing deforestation, mobilizing $1.3 trillion in climate financing that nations had agreed to during last year’s COP29, ensuring that worldwide decarbonization occurs in an equitable manner, and strengthening countries’ “nationally determined contributions,” or NDCs — national plans produced every five years that detail exactly how countries aim to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

As the conference stretched into its second and final week, momentum for Brazil’s fossil fuel transition road map seemed to grow, especially among Latin American countries, the United Kingdom, and the European Union. André Corrêa do Lago, vice minister for climate, energy and environment at the Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the official leader of COP30, rapidly got more than 90 nations to support putting a shift away from fossil fuels at the heart of the deal coming together in Belém. (The final agreements at each COP are adopted by consensus among negotiating parties, which include career diplomats, former ambassadors, environment ministers, and large teams of supporting staff for each country; the U.K., for example, had about 70 people officially involved in their negotiations.)

On Tuesday of last week, when the first draft of the deal was released, the language was a more forceful commitment to a global energy transition than most attendees were expecting. The agreement — several pages of proposed commitments that do Lago termed the “Global Mutirão,” using a word belonging to the Tupian languages of South America that signifies collective work — included a line indicating that the agreement “decides to establish” a “Belém Roadmap to 1.5,” a reference to the most ambitious temperature target adopted at Paris in 2015. The word “decides” turned heads, as it suggested legally binding authority.

“It would have been crazy,” said Felix Finkbeiner, founder of a conservation organization called Plant for the Planet who has been attending COPs since 2010. “Transitioning away from fossil fuels was set as a vague goal at COP28, but this would have been an actual process that initiated a massive step forward.”

Just days later, however, do Lago’s dream of making the first Amazonian COP a historic success was on the verge of falling apart. A new draft, published on the last official day of the conference, included no mention of a fossil fuel road map at all, triggering a flurry of new negotiations that stretched late into the night on Friday. Two cruise ships housing some four thousand COP attendees, including many delegates, needed to depart on Saturday morning no matter what. A deal had to be struck.

As the conference stretched past its official ending time, the parties negotiating behind closed doors became increasingly frustrated with the lack of movement on the fossil fuel road map. The obstacles to success, said Peter Wittoeck, one of the negotiators for Belgium, were the same oil-rich countries that had been blocking more ambitious action on climate change at COPs for decades.

“The major pushback is coming from the Like-Minded Developing Countries and the Arab Group,” Wittoeck said, referring, in the former case, to a coalition of large emerging economies that includes China, India, and South Africa, as well as a group of 20 Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Those nations, he said, “represent fossil fuel interests, obviously, and the fear of being limited in their economic development.”

The countries that had coalesced around the road map in the preceding days were enraged. “We are being silenced here,” said Irene Vélez Torres, director of the Colombian National Environmental Agency and one of the negotiators working on behalf of Colombia.

“I am saying it with a heavy heart, but what is now on the table is clearly no deal,” said European Union Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra. But some developing nations, including those on the front lines of destructive climate impacts, said that agreeing to a road map away from fossil fuels would unfairly limit their economic growth. “Countries that have used all sources of energy in the last 200 years and have achieved the pinnacle of industrial growth and yet not stopped using all those sources of energy are telling us ‘stop growing,’” Aisha Humaira, the head of the delegation for Pakistan, told The Guardian.

At the height of the drama on Friday night, members of the European Union suggested they might have to walk out of negotiations over the road map. “It’s not possible to have less ambition than we had 10 years ago,” said Petr Hladík, environment minister for Czechia, outside the negotiating rooms. United Kingdom Energy Minister Edward Miliband called the process “painful, difficult, and frustrating.”

The E.U. and the U.K. talked a big game, and Latin American countries like Colombia put up a fierce fight, but when the conference ended, new language on fossil fuels was nowhere to be found in the final document. The U.N. climate talks operate on consensus, and with the U.S. absent from negotiations, proponents of stronger language against fossil fuels faced a stronger, more organized bloc of countries, including two of the world’s largest economies in China and India, who also represent more than a third of the world’s population.

So what did survive the heated negotiations? To everyone’s surprise, the biggest agenda item to come out of COP30 was a plan for rich countries to help poorer nations strengthen themselves against the consequences of hurricanes, wildfires, droughts, and other climate impacts — an idea that has long lingered around the edges of COP negotiations. But even that win didn’t come easy.

For years, one of the foundational planks of international climate negotiations has been the notion that the rich countries most responsible for causing climate change have a responsibility to help poorer developing countries prepare for problems that they have done comparatively little to cause. This preparation might include infrastructure projects like seawalls, levees, flood control measures, water preservation systems, and home-hardening initiatives. The so-called Least Developed Countries, a negotiating bloc of nations including Bangladesh, Chad, Haiti, and Tuvalu, call this “survival funding.”

But this financing, known as adaptation funding, has always taken a back seat to financing for mitigation, which is typically the work of building out renewable sources of energy. That’s generally because those who fund mitigation have a clearer path to earning a return on their investments than those who fund adaptation. In other words, it’s less obvious how to make money off of sea walls and flood control systems than it is from green energy.

Still, adaptation aid for developing nations is one of the pillars of the original Paris Agreement — not just a charitable notion. The European Union, Japan, and other donor countries have a legal responsibility under the agreement to send money through this pipeline.

But how much money, how quickly it’s delivered, and what kinds of projects it should fund has always been a matter of debate. This year, it stormed into the spotlight, and it’s not hard to see why. The consequences of climate change have begun to spill into plain view, and countries are starting to feel serious economic pressure as a result. Gallagher Re, a global reinsurance broker, estimates that the direct cost of natural perils around the world in 2024 totaled a staggering $417 billion. Public and private insurance companies covered more than $150 billion of that, meaning the rest of the balance was covered by governments, policyholders, taxpayers, and everyday people.

The Least Developed Countries and the Africa Group, a bloc of African nations, don’t always have the same set of priorities, despite having some of the same member countries. But a member of Kenya’s negotiating team, who spoke on the condition of anonymity given the ongoing nature of negotiations, told Grist that the two groups combined forces to push for more adaptation financing. That strategy apparently paid off. As the conference entered its frenzied final week, this mega-coalition of countries pushed the European Union, the United Kingdom, and other developed countries to up their adaptation financing commitments.

European negotiators told Grist that the focus on adaptation put them in a tough spot. In the absence of a U.S. presence at COP, Europe has sought to position itself as the de facto global leader on climate action by trying to force the fossil fuel road map language into the final text. But its negotiators quickly found that the developing countries they were trying to align themselves with were laser-focused on adaptation financing.

“The situation now seems that we are not able to gather critical mass around the balance between high mitigation and being reasonable toward developing countries on adaptation,” said Wittoeck in the midst of negotiations.

But increased international aid is a tougher sell than it was even just a few years ago. Over the past several years, European leaders have been trying in vain to tamp down the slow creep of far-right parties in the union’s member states while simultaneously trying to salvage the European Green Deal, a plan to reach carbon neutrality by mid-century. Russia’s ongoing war with Ukraine has further complicated matters. The E.U. and the U.K. recently repurposed climate resilience aid for military spending.

“The world has changed,” said Joe Thwaites, a senior advocate for international climate finance at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “They are feeling the political strain back home and are very sensitive to headlines about how much money is being spent internationally.”

The final deal on adaptation, reached in the early hours of Saturday morning, stated that developed nations must at least triple their adaptation financing by 2035. The language is either historically ambitious or epically subpar, depending on who you ask. A previous deal reached at COP26 in Glasgow dictated that adaptation finance would double by 2025 to $40 billion per year, a number countries have not been able to reach. That deal expires this year, and members of the Africa Group and others hoped to include language in the text specifying that the tripling of adaptation funding should be based on that $40 billion number, meaning a new goal of $120 billion per year. Plus, they wanted the tripling to occur by 2030, not 2035.

The final version of the deal does not specify what the baseline number is, which means different countries might use different figures for their calculations. “I find it a bit vague,” the Kenya negotiator told Grist, adding that “the current needs are so huge that even the $120 billion is a drop in the ocean.” (The U.N. estimates that countries need as much as $400 billion per year to properly respond to climate change.)

Still, the boost in adaptation funding was a welcome development for many countries at the conference. “This was our priority and we made it a red line,” said Evans Njewa, chair of the Least Developed Countries group.

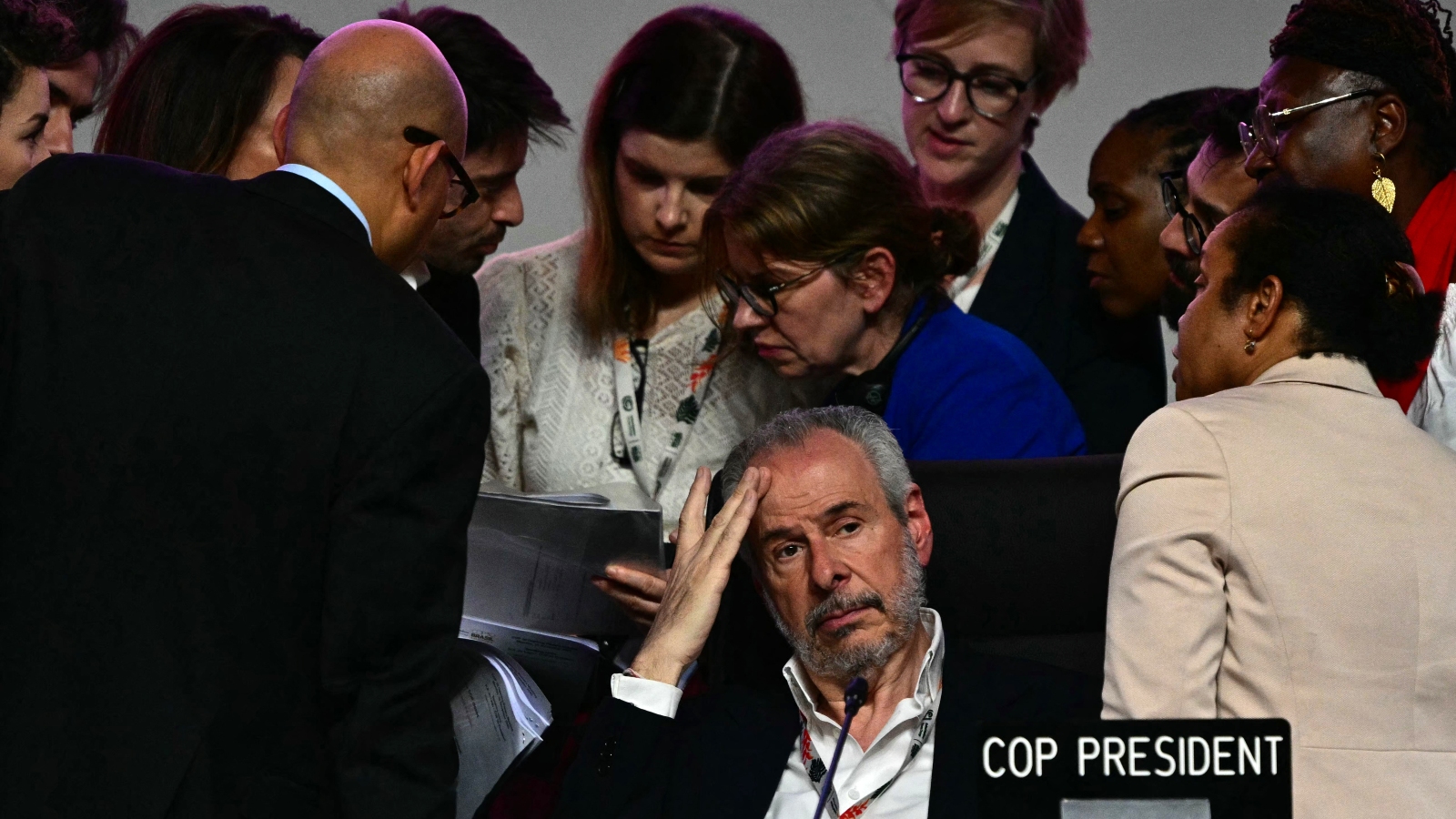

With the fossil fuel road map off the table and a deal on adaptation financing inked, the exhausted COP boss do Lago affirmed the COP30 consensus agreement on Saturday afternoon to loud applause. But the final conference plenary was engulfed in drama again just moments later, when Colombia’s Daniela Duran Gonzalez, head of international affairs for the Colombian Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, registered an objection. In his haste to end the conference, do Lago had inadvertently passed over a point of order raised by Colombia during the gaveling of the main agreement text. Gonzalez, and representatives of many other nations, wanted the final agreement to include language around fossil fuels.

“The COP of the truth cannot support an outcome that ignores science,” Gonzalez said.

Do Lago had to pause the plenary to confer with Colombia and other nations. After 30 minutes of haggling, the parties came back to the table to finish the conference with an agreement to continue conversations in the future. Do Lago also promised to launch two road maps of his own, one aimed at phasing out fossil fuels and the other in service of ending deforestation. Those efforts will take place outside the binding authority of the Paris Agreement, however, and are essentially opt-in endeavors.

Nevertheless, do Lago’s promise to continue fighting for a fossil fuel phaseout, paired with an announcement that Colombia and The Netherlands will host a first-ever international conference on a fossil fuel phaseout in 2026, proves that the mitigation conversation soldiers on.

“Today was a good day for multilateralism; it was a mixed day for the climate,” Jennifer Morgan, a former climate envoy for Germany, told Grist.

“Clearly the decisions here don’t put us on track for 1.5, but they accelerate implementation,” she added. “Gosh, we have so much more work to do.”

Editor’s note: The Natural Resources Defense Council is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline 10 years after the Paris Agreement, world leaders are letting go of its most famous goal on Nov 23, 2025.

This post was originally published on Grist.