On 29 September 2025 a multi-story musala (prayer space) collapsed at Pesantren Al-Khoziny in Sidoarjo, East Java, killing at least 61 people. A similar tragedy occurred again about a month later on 29 October, when the roof of a female student dormitory collapsed at Pesantren Syekh Abdul Qodir Jaelani in Situbondo, East Java, claiming the life of one student.

The level of anger and breadth of debate that followed—from demands for criminal investigations and critiques of pesantren governance structures to reflections on how pesantren constitute a distinct subculture within Indonesia’s educational and social systems—illustrate common perceptions about the importance of pesantren in Indonesian society. Observers have argued that pesantren occupy a key role in shaping grassroots political outcomes, whether through the political socialisation of santri (students), the broader authority of pesantren networks in local governance and policy debates, or the general political influence of kyai (religious leaders).

Without denying the significance of these findings, we nonetheless lack some basic empirical foundations for systematically measuring the social and political effects of pesantren. Claims about the importance or uniqueness of pesantren often rest on a handful of notable—and likely atypical—cases, such as Pesantren Tebuireng, which produced national leaders like Gus Dur and Ma’ruf Amin, or Pesantren Al-Mukmin in Ngruki, associated with allegations of terrorism. To more systematically understand the place, role, and effects of pesantren in Indonesian society as a whole, we first need answers to fundamental questions: how many pesantren are there? Where are they located? What are their organisational affiliations? Without such baseline information, it remains difficult to ascertain how prevalent pesantren truly are and how far-reaching their influence extends.

This piece takes a step forward by providing systematic, nationally representative background information on Indonesia’s pesantren landscape. Rather than engaging in an in-depth look at few pesantren, it embraces a bird’s-eye view of pesantren across the archipelago. The analysis addresses key descriptive questions about the number, location, organisational affiliation, and growth of pesantren over time, and offers preliminary evidence on how pesantren presence correlates with political outcomes.

Data for this exercise was scraped from the Ministry of Religious Affairs’ (MORA) Education Management Information System (EMIS). First introduced in the early 2000s, EMIS is a MORA’s effort to monitor and supervise religious educational institutions, which include pesantren and madrasah. School administrators enter data into the system following specific forms tapping into different information. Information recorded from each institution includes the number of educators, the number of students, available classrooms and other facilities, founding year, and affiliation, among others.

Interested users may access a subset of this dataset on my website. This dataset includes records on all pesantren, but omits several columns such as bank account information and staff contact details.

Number, location, and affiliation

The simplest analysis to do with the dataset would be to understand how many pesantren are there and where they are located. This question turns out to be more complicated than it looks.

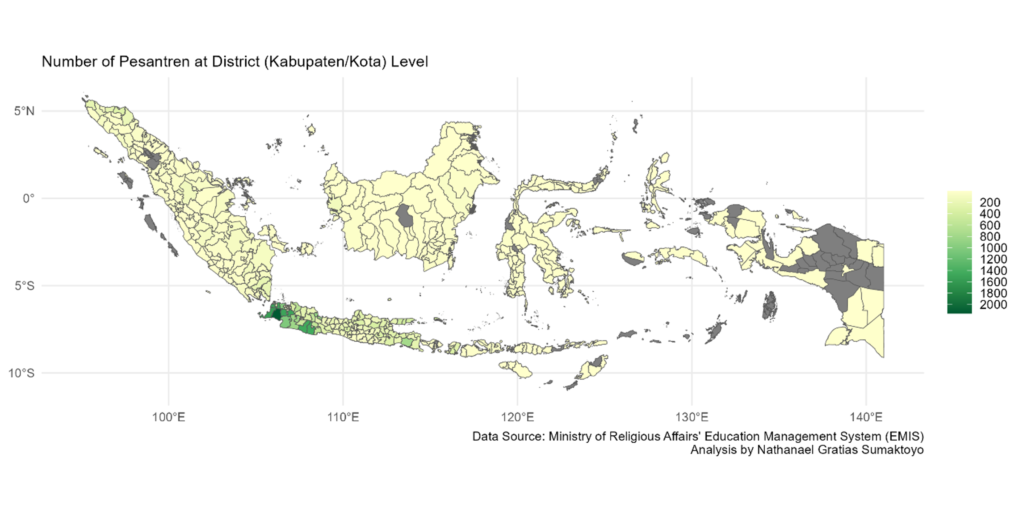

The EMIS website indicates that there are 42,391 pesantren. However, 20 of these records are duplicates and, out of the non-duplicates, 23 have broken links, which means their data could not be retrieved. We can thus reasonably assert that there are at least 42,348 pesantren in Indonesia. Figure 1 visualises the distribution of these pesantren at the district (kabupaten/kota) level. Some districts are shaded grey, which means that I was unable to link location information of the pesantren data with the GADM (Global Administrative Areas) map I used to create the choropleth.

One notable pattern in the figure concerns how districts in West Java and Banten tend to have the most pesantren. Is it simply because districts there are more populated than other districts in the country?

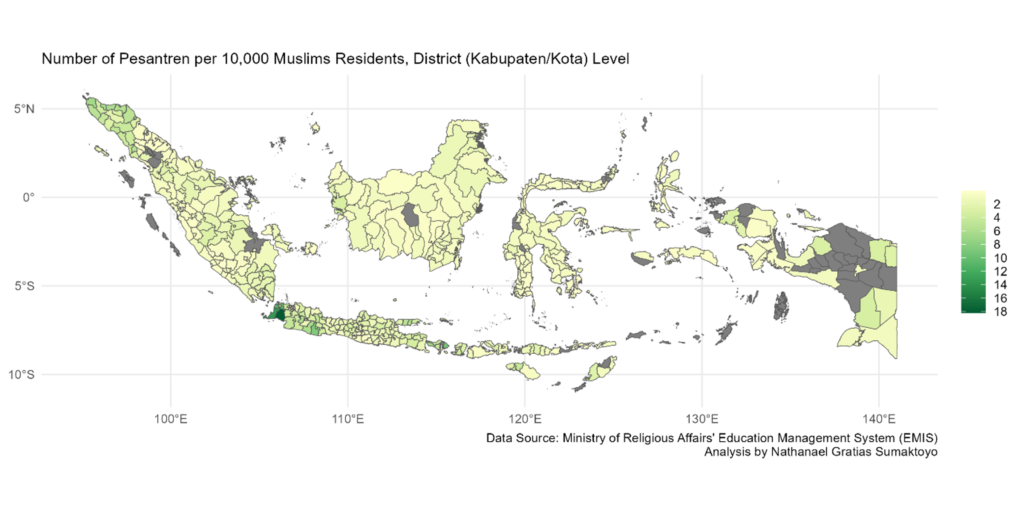

Figure 2 offers a more nuanced picture by showing the density of pesantren—that is, how many pesantren there are for every 10,000 Muslim residents in the district. The latter information was based on the 2010 census. The general pattern remains the same. Banten and West Java districts have the highest pesantren densities. However, districts in Aceh have darker shades than they are in Figure 1. In other words, even though there are fewer pesantren in Aceh than in Banten or West Java, once we account for population size, Aceh districts are generally comparable to West Java ones (though perhaps not Banten ones) in how prevalent pesantren are.

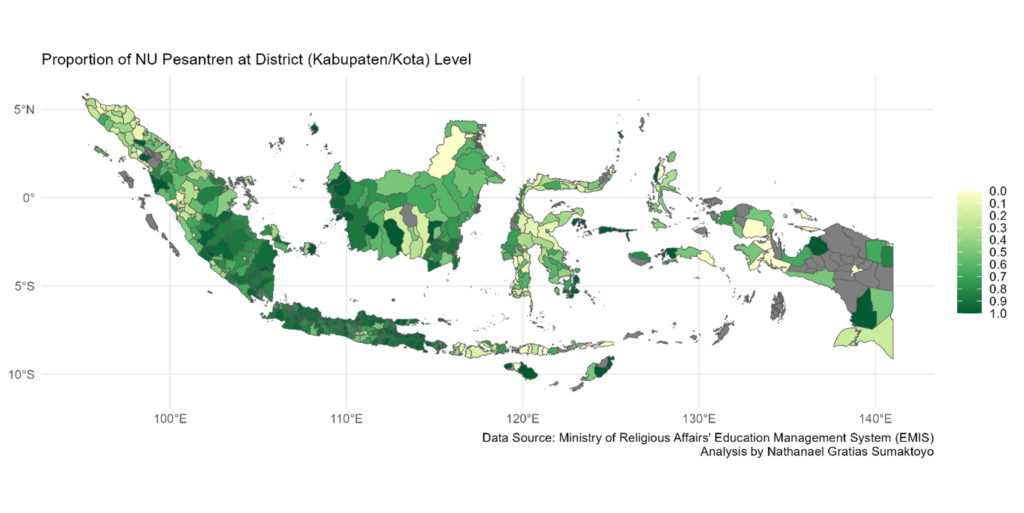

The next interesting exercise would be to unpick the affiliations of these pesantren. One notable feature of EMIS is that it asks pesantren to indicate their organisational affiliation. Overall, about 77.5% of pesantren indicate affiliation with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and about 15.6% indicate that they are independent or unaffiliated. The remaining 7% indicate various affiliations, such as with Muhammadiyah (1.54%), Nahdlatul Wathan (0.84%), and the Persatuan Tarbiyah Islamiyah (PERTI, 0.42%).

Figure 3 presents the proportion of NU pesantren in each district. In the vast majority of districts, the pesantren landscape is dominated by NU. However, some interesting exceptions are evident. In Aceh, NU pesantren tend to be less dominant. Of all pesantren in Aceh, only 23.3% indicate an affiliation with NU. The vast majority (64.9%) indicate being unaffiliated. PERTI also has a quite significance presence in the province, accounting for about 4.4% of the pesantren there.

Independent pesantren are also dominant in East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) and Central Sulawesi, where they account for 46.3% and 34.6% of the pesantren, respectively. The most popular affiliations differ in NTT and Central Sulawesi, however. In NTT, after NU at 29.3%, Muhammadiyah (12.20%) and Hidayatullah (4.9%) are the most popular affiliations. In Central Sulawesi, after NU at 27%, the most popular affiliations are Al Khairaat (18.05%) and DDI or Darud Dawah wal Irsyad (6%).

Growth

Having examined spatial variation, we can also look at temporal variation or how the number of pesantren grew over time. EMIS asked pesantren to indicate their founding year in both international and Islamic calendars. Unfortunately, many of the entries look implausible, and judgment calls have to be made to keep only pesantren with plausibly valid information about their founding year in the dataset.

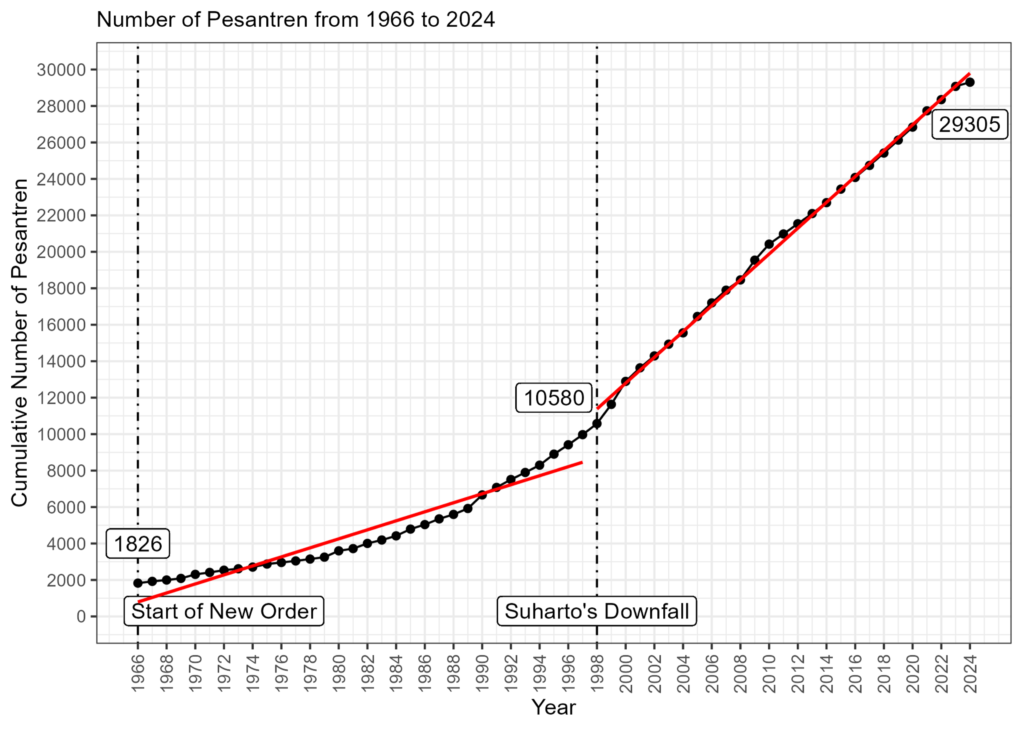

First, I removed 3,010 pesantren that indicated founding years earlier than 1475 AD. This is the founding year of Pesantren Alkahfi Somalanguk, which some regard as the oldest pesantren in Indonesia. Second, I removed 33 pesantren that indicate founding years after 2025—the current year. Lastly, I removed 7,628 pesantren whose founding year in the international calendar does not match its founding year in the Islamic calendar. Such a mismatch makes it impossible for an analyst to decide whether to use information from the international calendar or the Islamic calendar. It might also indicate sloppy data entry. Overall, 29,305 pesantren have information about founding year that I consider valid.

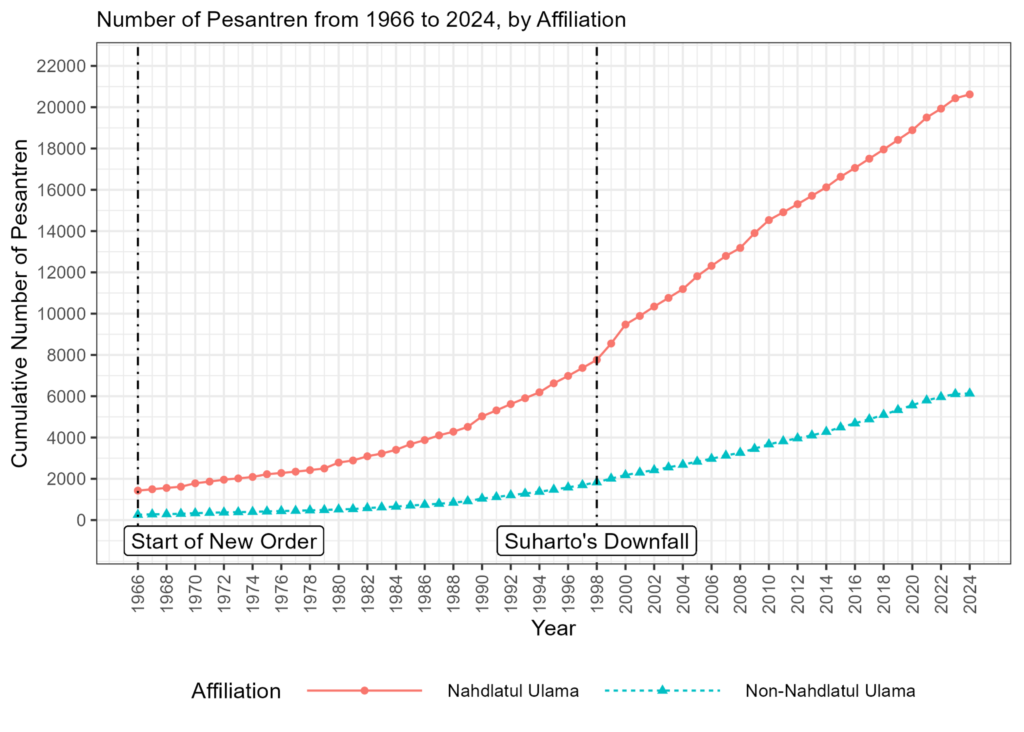

Figure 4 draws from this information and presents the cumulative number of pesantren between 1966 and 2024. I treat this growth chart as a disrupted time series and draw two regression lines, one for the New Order era and the other for the post-Suharto era. This allows us to compare the pattern of pesantren-building during the two eras.

Two patterns are evident from this figure. First, it is obvious that the growth rate of pesantren in the post-Suharto era is higher than the rate during the New Order, as evidenced by the steeper slope of the post-Suharto regression line. This conforms to what we know about how Indonesia’s democratisation was accompanied by a religious resurgence.

Second, we can actually observe a minor spike in the number of pesantren starting in early 1990s. There, the number of pesantren is higher than what the New Order regression line predicts. This nicely reflects Suharto’s growing affinity with Islam at the time, evidenced among others by the founding of the Indonesian Association of Muslim Intellectuals (ICMI) in 1990 and Suharto’s hajj pilgrimage in 1991.

Figure 5 breaks down this growth by organisational affiliation. It is evident that much of the growth was driven by the proliferation of NU pesantren. At the start of the New Order, NU pesantren numbered 1,428 and non-NU pesantren 258. By the time Suharto was removed from power in 1998, there were 7,764 NU and 1,833 non-NU pesantren. By 2024, these numbers grew to 20,620 NU and 6,134 non-NU pesantren. It seems that, at least when it comes to pesantren building, the religious resurgence that followed Indonesia’s democratisation has not affected all Muslim organisations equally.

Pesantren and politics

Lastly, it is interesting to measure whether the presence of pesantren may correlate with electoral outcomes. It goes without saying that correlation does not necessarily mean causation. But ascertaining how pesantren density may be associated with electoral outcomes is a foundational step in understanding how pesantren are significant not only socially but also politically.

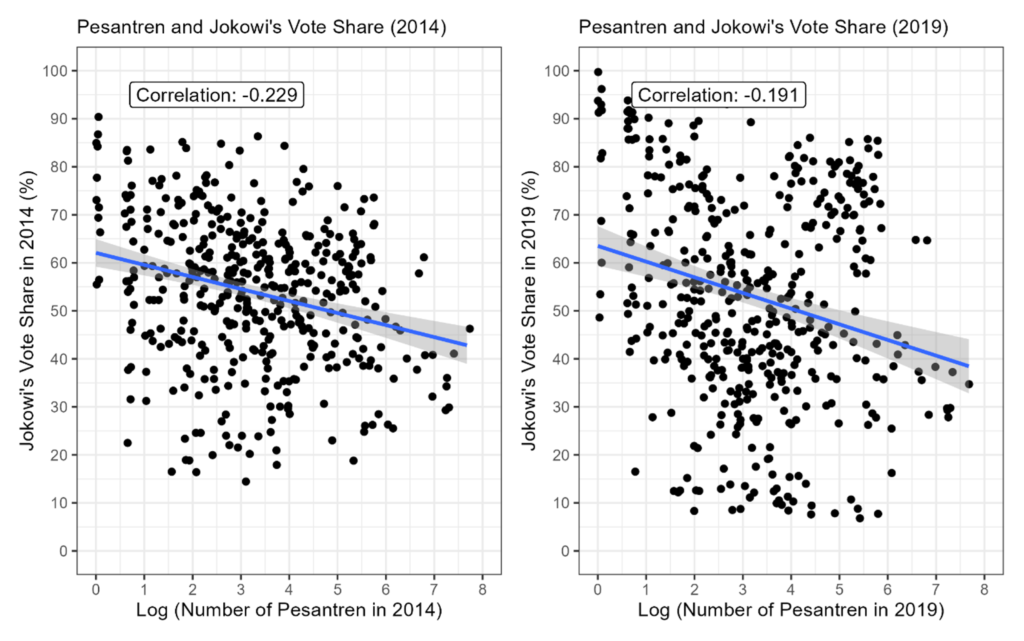

I start by examining how the number of pesantren in a district correlates with the vote share of Joko Widodo (Jokowi) in the 2014 and 2019 presidential elections. The presidential elections were often portrayed as a competition between Jokowi’s nationalist camp and Prabowo’s Islamist supporters. To the extent that pesantren correlates with religious sentiment and identity, we should observe a negative correlation between the number of pesantren and Jokowi’s vote share.

Figure 6 shows exactly this pattern. Each dot reflects a district. The X axis represents the logged number of pesantren in the election year and the Y axis represents Jokowi’s vote share. The negative correlations indicate that the more pesantren a district had, the lower the vote share of Jokowi in that district.

Interestingly, the correlation was weaker in 2019 than 2014. This might be a result of the Ma’ruf Amin effect. By having Ma’ruf, a popular NU cleric and former chairman of the Indonesian Council of Ulama (MUI) as running mate, Jokowi was able to weaken Islamist voters’ opposition against him.

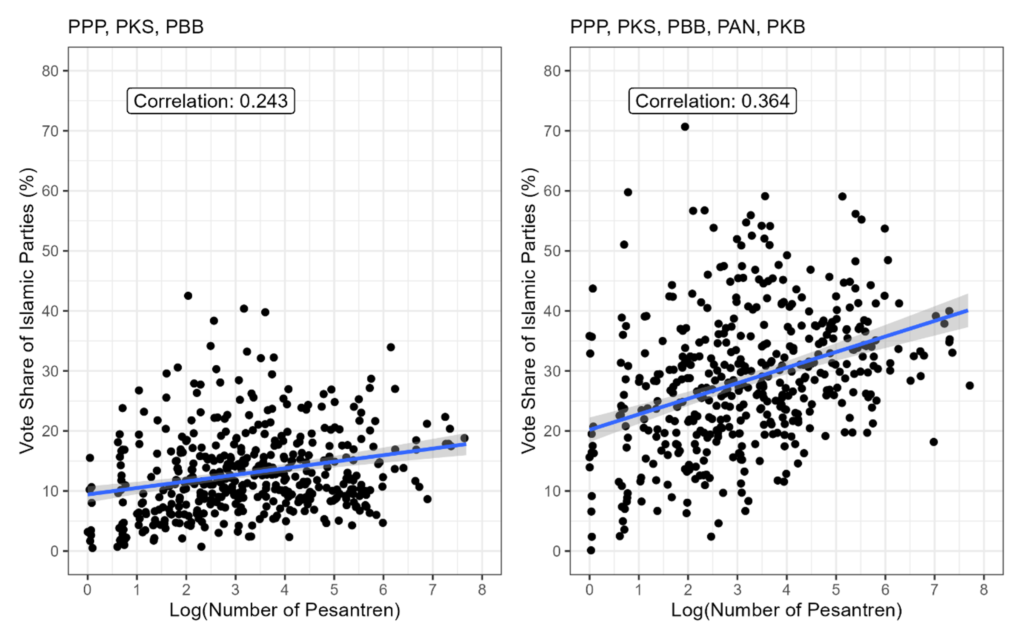

Figures 7 and 8 approach the question from the perspective of party competition. Figure 7 plots the correlations between the number of pesantren and the vote share of Islamic parties in the 2019 parliamentary election. Counting only the United Development Party (PPP), the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), and the Crescent Star Party (PBB) as Islamic parties, the correlation is a modest (r=.243). The higher the number of pesantren in a district, the higher the vote share of Islamic parties. Adding the National Mandate Party (PAN) and the National Awakening Party (PKB) strengthens this correlation. But even then, the correlation is not particularly strong, as the number of pesantren only explains about 13% of Islamic parties’ vote share.

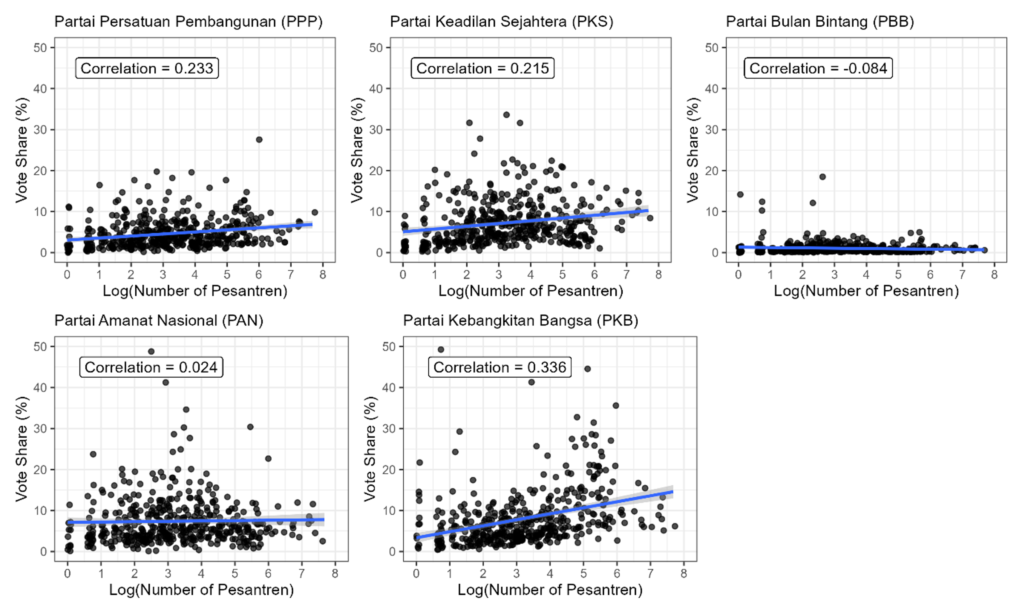

Figure 8 breaks down the vote share of Islamic parties into individual party’s vote share. Given how pesantren are predominantly NU-affiliated, it is unsurprising that the correlation between pesantren and vote share is strongest for PKB, widely regarded as an NU-linked party. The correlation with PPP is also relatively unsurprising, considering it was the product of a fusion of Islamic parties in 1973 (including the former NU party) and has ties with traditional Muslims.

Perhaps the most surprising pattern from Figure 8 is the respectable correlation between pesantren and PKS’s vote share. As a party that grew out of student movements and urban Muslims, PKS is not generally associated with pesantren and their traditionalist Islamic networks. However, the modest correlation suggests that the party has successfully made inroads into pesantren-based and traditionalist Muslim voters.

Conclusion

My analysis provides background information about pesantren in Indonesia, offering new foundational empirical insights for systematically studying the social

Social media offers an ersatz form of accountability

Indonesia’s democracy is becoming reactive. Is that good?

Other findings are less intuitive, for example about how the predominance of NU pesantren varies across provinces and about how PKS’s vote share is quite strongly related to the number of pesantren in a district. These analyses are preliminary and relatively basic. As mentioned, without making any claims about the accuracy of this data, I have made the data available for public use at my website.

Combining this dataset with other available data on Indonesia, researchers may explore deeper questions about Indonesia’s political and religious landscape. For example, researchers may combine pesantren data with survey data to examine how pesantren density correlates with public opinion about the role of Islam in public affairs. Alternatively, researchers may also combine pesantren data with that which measures religious tolerance and examine how the two may be related. All of these exercises will help us understand the roles and significance of pesantren in shaping Indonesia’s social and political life.

The post The pesantren archipelago appeared first on New Mandala.

This post was originally published on New Mandala.