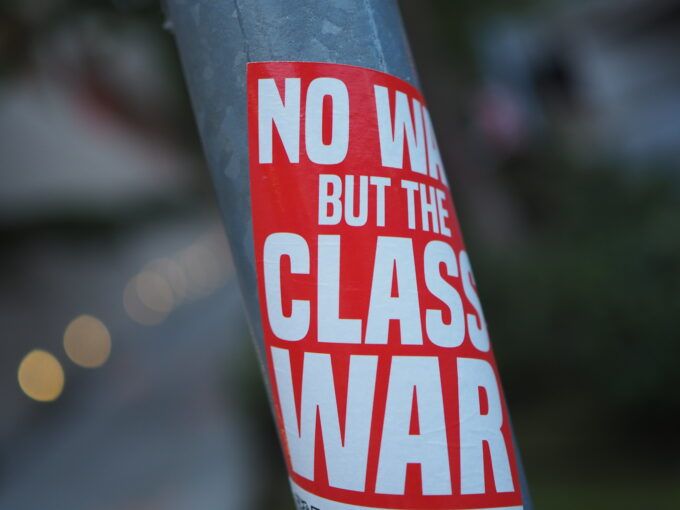

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

Cost-of-living conditions are a measure of class relations. According to a Statista Consumer Insights survey conducted in June and July 2025, “49 percent of U.S. adults said that the high cost of living was one of the biggest challenges they currently face – making it by far the most common answer.”

The billionaire corporations and the wealthy, attached to the political system, are benefiting. “The total wealth of the top 10% — or those with a net worth of more than $2 million — reached a record $113 trillion in the second quarter, up from $108 trillion in the first quarter,” CNBC’s Robert Frank writes, citing Federal Reserve Bank data. “The increase follows three years of continued growth for those at the top, with the top 10% adding over $40 trillion to their wealth since 2020.”

A driver of the wealth boom at the top is the stock market. The prices of so-called Magnificent Seven stocks of Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Nvidia, Meta, Microsoft and Tesla, are booming.

Meanwhile, a cost-of-living crisis festers on Main Street. Significantly, this working majority does not set prices or wages, the drivers of cost-of-living conditions.

It’s not an either or situation. “The roots of today’s affordability crisis actually lie not in recent price spikes,” according to Heidi Shierholz, President at the Economic Policy Institute and former chief economist at the U.S. Department of Labor, “but in the long-term suppression of workers’ pay.”

On that same note of wage-suppression, the working class labors largely union-free in the U.S. Private-sector workers, the majority of the American labor force, do not collectively bargain their wages, salaries and working conditions with employers.

Why? Anti-labor union policies are one of the main workplace conditions that have marked the postwar economy since the 1970s. Other anti-worker policies causing wage-suppression are corporate-driven globalization and excessive unemployment.

So-called free trade pacts like the NAFTA happened under Democratic President Clinton.

Corporations relocated to Mexico, where workers earn a fraction of the pay that their American counterparts receive.

The federal minimum wage has been stuck at $7.25 an hour since 2009, when President Obama was in the White House. He promised to sign the Employee Free Choice Act, an amendment to the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. With the EFCA, a simple majority of employees (50%) could check a card showing support to join a union at a workplace, replacing the National Labor Relations Board secret-ballot elections stacked in favor of employers.

First, however, the EFCA required enough votes to pass the Senate and House for President Obama to sign it into law, as he promised to. Democrats held a majority in the House and Senate in 2009-2011, Obama’s first term, but the bill never made it through the upper house.

Democrats had a majority in both chambers at the start of his presidency in the 111th Congress (2009-2011). The bill made it through the House but died in the Senate. “Several lobbying and consulting groups aligned with the Democratic Party were actively working with anti-union employers to defeat the EFCA,” according to the Arizona State University School Center for Work and Democracy.

The Democratic Party controlled the House and Senate when President Biden took office in January 2021. Recall that Biden said: “Nothing fundamental will change,” to his wealthy donors before winning the White House over Trump. Nothing fundamental changed in terms of reversing the fall of labor unions and rise of anti-union companies such as Walmart and Amazon.

Weakening unions has been a leading policy of neoliberalism, moving income and wealth from the bottom and middle to the top. Out with New Deal and Great Society policies for those who live on wages and salaries. In with policies for those who live on profits from investment capital.

Cut to today. The affordability crisis, the struggle to make ends meet, is a class struggle. That struggle is gaining traction electorally, beginning with the two presidential campaigns of Vermont independent senator Bernie Sanders.

A more recent case in point is the victory of mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, a democratic socialist, in NYC. How? He in part focused on rising prices of child care, food and rent compared with salaries and wages.

That is why the voters in NYC chose him as mayor recently. NYC’s response to systemic unaffordable child care, food and rent is, therefore, a conscious decision of the working class on behalf of its own self-interest, electorally speaking.

Therein lies a dilemma. I mean the fact that Democratic candidates, once elected, sell out their voters. By contrast, donors with deep pockets get what they demand, election after election.

This relationship profits donors. The politics of capitalist economics is a powerful force to contend with. There is no alternative to confronting this force, to paraphrase the late British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, proclaiming the power of liberal capitalism to rule via crushing opposition its opponents.

The popularity of Mr. Mamdani in NYC and Katie Wilson, mayor elect in Seattle, who like him focuses laser-like on policies to address the cost-of-living crisis for working families, suggests that the electoral engagement of those who live on wages and salaries is rising. That’s a step forward but by no means a victory over a resilient economic system with a track record of crushing and co-opting political reforms that improve people’s lives.

The post Class Rules: The Struggles of U.S. Workers appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.