Announcing their hiring of Ben Smith, New York Times editors (1/28/20) declared, “Ben not only understands the seismic changes remaking media, he has lived them — and in some cases, led them.”

In a time of downsizing and consolidation, Ben Smith has had a journalistic career many would envy. He became famous as the editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed News, and is co-founder and editor-in-chief of Semafor, a rising media giant that raised $19 million last year. (This “replac[ed] the money it had received from the disgraced cryptocurrency mogul Sam Bankman-Fried,” the New York Times reported—5/24/23).

These two adventures bookend his two-year stint as the “Media Equation” columnist at the New York Times, from March 2020 through January 2022. During his entire tenure there, Smith held an undisclosed amount of stock options in BuzzFeed, creating a conflict of interest for him and the Times, which both consistently waved away (Slate, 10/15/21). “Under New York Times policy, I can’t write about BuzzFeed extensively until I divest stock options in the company,” Smith explained on several occasions (here 9/26/21).

But from his influential perch, Smith did, of necessity, cover BuzzFeed’s competitors, frequently critically, putting his investment’s rivals and potential rivals in a bad light. Buzzfeed started out as pure internet culture, a website offering entertainment and quizzes. But it expanded into hard news, thus competing with others in that new media mold, like the nodes of the Gawker empire.

Smith’s stake in BuzzFeed exceeded $7 million, according to FAIR’s sources—a strikingly large material interest in a company whose competitors Smith regularly covered, underscoring the ethical concerns about both Smith’s coverage and the Times’ willingness to ignore its own ethical guidelines.

‘Well above my Times salary’

With a considerable financial stake in online media, Ben Smith could have different reasons from the rest of us for freaking out about Substack (New York Times, 4/11/21).

Smith (New York Times, 10/17/21) covered sexual harassment allegations at Axel Springer as the Berlin-based multimedia company was looking to grow its footprint in the US media market—making it a potential competitor to BuzzFeed.

In a critical piece (New York Times, 4/11/21) about the self-publishing platform Substack, which includes heavy investment from venture capitalist and Trump supporter Marc Andreessen, Smith wrote:

Substack has courted a number of Times writers. I turned down an offer of an advance well above my Times salary, in part because of the editing and the platform the Times gives me, and in part because I didn’t think I’d make it back—media types often overvalue media writers.

Smith appears to be putting his cards on the table here, but readers have no way of knowing that his financial interest in BuzzFeed far eclipsed the salary he was getting from the Times or was offered by Substack, a new media product that competed against the very company, BuzzFeed, he was invested in.

Smith (New York Times, 4/18/21) also pooh-poohed Bustle’s growth with Mic and Nylon, and its eye on restarting Gawker, in part because Bustle bet on advertising revenue, which Smith maintained was destined to flow overwhelmingly to Google and Facebook (later rebranded as Meta).

A month later, Bustle rebranded in preparation for its IPO (Axios, 5/11/21)—an initial public offering to investors. A month after that, Hollywood Reporter (6/30/21) noted that BuzzFeed was one of a number of media companies, including Bustle, that were looking to go public in order to shore up investments. Once again, readers should have had a clear understanding that Smith was writing about an entity that was competing for venture capital with the outlet he had major holdings in.

Downfall of a high-flying startup

A story by Smith in the New York Times (9/26/21) contributed to the downfall of the media startup Ozy—a company that Buzzfeed under Smith’s leadership considered buying.

The most interesting example of Smith’s conflict of interest is the case of Ozy Media. Carlos Watson, a former MSNBC and CNN anchor, attracted lots of attention when he launched Ozy, raising $5.3 million in its early days (Venture Capital Post, 12/28/13), reaching up to an enormous $20 million investment from Axel Springer (USA Today, 10/6/24). Watson and his media child were riding high—for a time.

Smith (New York Times, 9/26/21) was the first journalist to raise questions about the veracity of Ozy’s claims to investors. Less than two years later, Watson was arrested for fraud (Wall Street Journal, 2/23/23), and the operation was no more (Variety, 3/1/23). He and the company were ultimately found guilty in a New York City federal court earlier this year, “in a case accusing them of lying to investors about the now-defunct startup’s finances and sham deals with Google and Oprah Winfrey” (Reuters, 7/16/24). He was sentenced to 10 years in prison (AP, 12/16/24).

Smith’s reporting on Ozy was considered momentous, leading to the downfall of a high-flying media startup. But Smith was not a disinterested journalist when he went after Watson and Ozy. Late last year, Ozy sued Smith, BuzzFeed and Semafor for allegedly stealing Ozy’s trade secrets (Reuters, 12/21/23); in the initial complaint, Ozy’s legal team said that Smith was interested in BuzzFeed acquiring Ozy as early as 2019.

‘Sizable material stake’

It is also through this case that we have a better understanding of Smith’s financial interest in BuzzFeed during his time as a Times media columnist. According to FAIR’s sources, the prosecution obtained financial records from BuzzFeed in discovery that document how much stake Smith has had in the company over time. FAIR has not seen this sealed document; however, David Robinson, a business scholar at Duke University who served as an expert witness for the defense, did see it.

In an April filing in the case, Robinson noted that in Smith’s original report about Ozy, he disclosed that “Under New York Times policy, I can’t write about BuzzFeed extensively until I divest stock options in the company, which I left last year.” But, Robinson noted:

Columnist Benjamin Smith had, at the time of that article’s writing, an ownership stake in BuzzFeed in the form of stock options. Those options would become valuable if BuzzFeed went public later in 2021 in an initial public offering (IPO). In an IPO, options holders, such as Smith, are able to convert their options at the then-anticipated IPO price of $10 per share.

Analyzing BuzzFeed’s capital table, I calculated the number of Ben Smith’s outstanding split-adjusted shares. I then computed, for each option grant, the stock price minus the option exercise price multiplied by the number of options for each option grant, to arrive at the proceeds that Ben Smith would net upon selling his options. I estimate that Ben Smith’s options had an expected value of approximately $23,468,268.64.

On January 4, 2022, the New York Times announced that Smith had left the paper to start a new media company, one [that] “would aim to break news and offer nuance to complex stories, without falling into familiar partisan tropes.”

In a phone interview with FAIR, Robinson clarified that, since he issued this testimony, he revised his calculations based on BuzzFeed’s capitalization table. This reduced his estimate of Smith’s stake to $7.4 million, still a princely sum—and a valuation that he said, to his knowledge, hasn’t been challenged.

“I think he had a clear sizable material stake in BuzzFeed in the time when other corporations’ decisions were immediately impacting the value of BuzzFeed,” Robinson told FAIR. “I’m simply trying to bring to light the bias that seems to be apparent.”

A flexible deadline

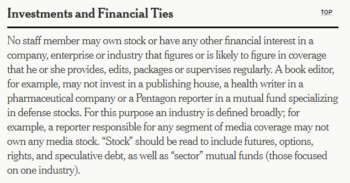

The New York Times‘ rules about financial conflicts cite as an example, “a reporter responsible for any segment of media coverage may not own any media stock”—and make clear that that includes options.

That Smith had a conflict of interest does not mean that all or indeed any of the reporting he published about BuzzFeed‘s rivals was untrue or unjustified. (Some of the outlets he criticized, like Substack and German media giant Axel Springer, are ones I’ve also critiqued at FAIR—3/4/21, 11/5/21). The problem with Smith’s conflict of interest is that it gave him a financial incentive to encourage the decline of these particular outlets. Times readers can’t know whether, or how much, this incentive factored into his journalistic decisions—especially as the scale of the conflict was not made clear to those readers.

Moreover, the Times has clear rules about stock ownership. Its ethics guidelines say:

No staff member may own stock or have any other financial interest in a company, enterprise or industry that figures or is likely to figure in coverage that he or she provides, edits, packages or supervises regularly.

In several early columns, Smith included disclaimers about the conflict. In a column (5/3/20) on union organizing in newsrooms that mentioned his experience at BuzzFeed, for instance, Smith included this disclosure:

I agreed with the Times when I was hired that I wouldn’t cover BuzzFeed extensively in this column, beyond leaning on what I learned during my time there, because I retain stock options in the company, which could bring me into conflict with the Times’ ethics standards. I also agreed to divest those options as quickly as I could, and certainly by the end of the year.

But this deadline was quietly extended—and BuzzFeed went public right before he left the Times (Vox, 12/6/21). It appears that he never wrote directly about BuzzFeed, but Slate‘s Justin Peters (10/15/21) noted that as the end-of-year deadline came and went, Smith’s columns stopped mentioning any sort of deadline by which he would divest. When Peters inquired with the Times, spokesperson Danielle Rhoades Ha said Smith’s deadline was extended until February 2022—two years after he was hired.

BuzzFeed went public in December 2021. Smith left the Times to start Semafor in January 2022.

Rhoades Ha told FAIR that Smith’s deadline was extended “due to the pandemic,” and that he “disclosed the options when relevant in that period.”

Smith and the media desk at Semafor did not respond to requests for comment.

A really big deal

Pointing out that it’s “bad for readers to have a media columnist whose motives they cannot absolutely trust to be disinterested,” Slate‘s Justin Peters (10/15/21) wrote that Smith “probably shouldn’t be writing about such a broad swath of digital media.”

Peters (Slate, 10/15/21) reported that neither Smith nor the Times explained why Smith stopped putting a divestment deadline on the investment disclosures in his columns. Further, he said:

Neither Smith nor Rhoades Ha responded to separate questions about why, exactly, the Times extended Smith’s divestment deadline, or whether the shifting deadline had anything to do with BuzzFeed’s plans to go public. But an SEC filing from July pertaining to BuzzFeed’s proposed SPAC merger—and an amended filing dated October 1—describes a 180-day post-merger lockup period during which certain stockholders and options holders are prohibited from transferring their shares.

The Times is not offering a sufficient answer. For one thing, it ignores the scope of Smith’s reported stake. Had he stood to gain a few thousand dollars from his former media employer while working on the media beat, big deal (sarcasm). But millions? Big deal (not sarcasm).

And there seems to be a betrayal of the spirit of the Times’ own codes about conflicts of interest when the deadline was extended for him; if the paper can bend the rules on the media beat, where else could it bend the rules? When FAIR told Robinson that the Times confirmed that the Smith’s deadline to divest had been extended, he countered, “What good is a stop sign if you tell people they’re free to run through it?”

“Given that he was a senior executive, it stands to reason he’d have a significant stake in the company,” Robinson said of Smith and BuzzFeed. “I just think it’s not appropriate for him to be writing about the company’s competitors.”

This post was originally published on FAIR.