Janine Jackson interviewed EarthRights International’s Kirk Herbertson about Big Oil’s lawsuit against Greenpeace for the February 28, 2025, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript.

EarthRights (2/20/25)

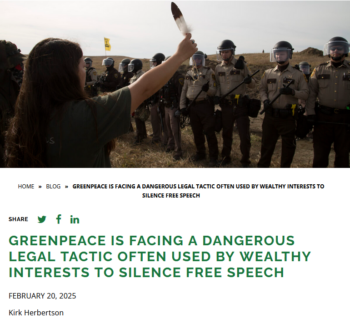

Janine Jackson: Energy Transfer is the fossil fuel corporation that built the Dakota Access Pipeline to carry fracked oil from the Bakken Fields more than a thousand miles into Illinois, cutting through unceded Indigenous land, and crossing and recrossing the Missouri River that is a life source for the Standing Rock tribe and others in the region.

CounterSpin listeners know that protests launched by the Indigenous community drew international attention and participation, as well as the deployment, by Energy Transfer’s private security forces, of unleashed attack dogs and pepper spray, among other things, against peaceful protestors.

Now Energy Transfer says it was harmed, and someone must pay, and that someone is Greenpeace, who the company is suing for $300 million, more than 10 times their annual budget. No one would have showed up to Standing Rock, is the company’s story and they’re sticking to it, without the misinformed incitement of the veteran environmental group.

Legalese aside, what’s actually happening here, and what would appropriate reporting look like? We’re joined by Kirk Herbertson, US director for advocacy and campaigns at EarthRights International. He joins us now by phone from the DC area. Welcome to CounterSpin, Kirk Herbertson.

Kirk Herbertson: Thanks so much, Janine.

JJ: Let me ask you, first, to take a minute to talk about what SLAPP lawsuits are, and then why this case fits the criteria.

KH: Sure. So this case is one of the most extraordinary examples of abuse of the US legal system that we have encountered in at least the last decade. And anyone who is concerned about protecting free speech rights, or is concerned about large corporations abusing their power to silence their critics, should be paying attention to this case, even though it’s happening in North Dakota state court.

As you mentioned, there’s a kind of wonky term for this type of tactic that the company Energy Transfer is using. It’s called a SLAPP lawsuit. It stands for “strategic lawsuit against public participation.” But what it really means is, it’s a tactic in which wealthy and powerful individuals or corporations try to silence their critics’ constitutional rights to free speech or freedom of assembly by dragging them through expensive, stressful and very lengthy litigation. In many SLAPP lawsuits, the intention is to try to silence your critic by intimidating them so much, by having them be sued by a multimillion, multibillion dollar corporation, that they give up their advocacy and stop criticizing the corporation.

JJ: Well, it’s a lot about using the legal system for purposes that most of us just don’t think is the purpose of the legal system; it’s kind of like the joke is on us, and in this case, there just isn’t evidence to make their case. I mean, let’s talk about their specific case: Greenpeace incited Standing Rock. If you’re going to look at it in terms of evidence in a legal case, there’s just no there there.

KH: That’s right. This case, it was first filed in federal court. Right now, it’s in state court, but if you read the original complaint that was put together by Energy Transfer, they referred to Greenpeace as “rogue eco-terrorists,” essentially. They were really struggling to try to find some reason for bringing this lawsuit. It seemed like the goal was more to silence the organization and send a message. And, in fact, the executive of the company said as much in media interviews.

Civil litigation plays a very important role in the US system. It’s a way where, if someone is harmed by someone else, they can go to court and seek compensation for the damages from that person or company or organization, for the portion of the damages that they contributed to. So it’s a very fair and mostly effective way of making sure that people are not harmed, and that their rights are respected by others. But because the litigation process is so expensive, and takes so many years, it’s really open to abuse, and that’s what we’re seeing here.

JJ: Folks won’t think of Greenpeace as being a less powerful organization, but if you’re going to bring millions and millions of dollars to bear, and all the time in the world and all of your legal team, you can break a group down, and that seems to be the point of this.

North Dakota Monitor (3/3/25)

KH: Absolutely. And one of the big signs here is, the protests against the Dakota Access pipeline were not led by Greenpeace, and Greenpeace did not play any sort of prominent role in the protests.

These were protests that were led by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, who was directly affected by the pipeline traveling through its primary water source, and also traveling a way where they alleged that it was violating their treaty rights as an Indigenous nation. So they started to protest and take action to ask for this pipeline not to be approved. And then it inspired many other Indigenous tribes around the country, many activists, and soon it grew into a movement of thousands of people, with hundreds of organizations supporting it both in the US and internationally. Greenpeace was one of hundreds.

So even in the case where Energy Transfer’s “damaged” and wants to seek compensation for it, it’s really a telltale sign of this abusive tactic that they’re going after Greenpeace. They have chosen to go after a high-profile, renowned environmental organization that played a very secondary role in this whole protest.

JJ: So it’s clear that it’s symbolic, and yet we don’t think of our legal system as being used in that way. But the fact that this is not really about the particulars of the case, an actual harm being done to Energy Transfer by Greenpeace, that’s also made clear when you look at the process. For example, and there’s a lot, the judge allowed Energy Transfer to seal evidence on their pipeline safety history. There are problems in the process of the way this case has unfolded that also should raise some questions.

NPR (2/22/17)

KH: That’s right. So when the case was first filed–I won’t go through the full timeline of the protests and everything that happened. It’s very in-depth, and it’s well-covered online. But the pipeline became operational in June 2017, and a little over one month later, that’s when the first lawsuit was filed against Greenpeace and others.

And that first lawsuit was filed in federal court. Energy Transfer brought it into federal court, and they tried to claim at that point that Greenpeace was essentially involved in Mafia-like racketeering; they used the RICO statute, which was created to fight against the Mafia. That’s when they first alleged harm, and tried to bring this lawsuit.

The federal court did not accept that argument, and, in fact, they wrote in their decision when they eventually dismissed it, that they gave Energy Transfer several opportunities to actually allege that Greenpeace had harmed them in some way, and they couldn’t.

So it was dismissed in federal court, and then one month later, they refiled in North Dakota state court, where there are not these protections in place. And they filed in a local area, very strategically; they picked an area close to where there was a lot of information flowing around the protest at the time. So it was already a situation where there’d already been a lot of negative media coverage bombarding the local population about what had happened.

So going forward, six years later, we’ve now started a jury trial, just in the last week of February. We’ll see what happens. It’s going to be very difficult for this trial to proceed in a purely objective way.

JJ: And we’re going to add links to deep, informative articles when we put this show up, because there is history here. But I want to ask you just to speak to the import of it. Folks may not have seen anything about this story.

First of all, Standing Rock sounds like it happened in the past. It’s not in the past, it’s in the present. But this is so important: Yesterday I got word that groups, including Jewish Voice for Peace, National Students for Justice in Palestine, they’re filing to dismiss a SLAPP suit against them for a peaceful demonstration at O’Hare Airport. This is meaningful and important. I want to ask you to say, what should we be thinking about right now?

Kirk Herbertson: “This is a free speech issue that in normal times would be a no-brainer.”

KH: There’s a lot of potential implications of this case, even though it’s happening out in North Dakota state court, where you wouldn’t think it would have nationwide implications.

One, as you mentioned, this has become an emblematic example of a SLAPP lawsuit, but this is not the first SLAPP lawsuit. For years, SLAPPs have been used by the wealthy and powerful to silence the critics. I could name some very high-profile political actors and others who have used these tactics quite a bit. SLAPPs are a First Amendment issue, and there has been bipartisan concern with the use of SLAPPS to begin with. So there are a number of other states, when there have been anti-SLAPP laws that have passed, they have passed on an overwhelmingly bipartisan basis.

So just to say, this is a free speech issue that in normal times would be a no-brainer. This should be something that there should be bipartisan support around, protecting free speech, because it’s not just about environmental organizations here.

I think one of the big implications of this trial going forward at this time, in this current environment, is that if Energy Transfer prevails, this could really embolden other corporations and powerful actors to bring copycat lawsuits, as well as use other related tactics to try to weaponize the law, in order to punish free speech that they do not agree with.

And we’ve seen this happen with other aspects of the fossil fuel industry. If something is successful in one place, it gets picked up, and used again and again all over the country.

JJ: Well, yes, this is a thing. And you, I know, have a particular focus on protecting activists who are threatened based on their human rights advocacy, and also trying to shore up access to justice for people, and I want to underscore this, who are victims of human rights abuses perpetrated by economic actors, such as corporations and financial institutions. So I’m thinking about Berta Caceres, I’m thinking of Tortuguita.

I don’t love corporate media’s crime template. It’s kind of simplistic and one side, two sides, and it’s kind of about revenge. And yet I still note that the media can’t tell certain stories when they’re about corporate crimes as crimes. Somehow the framework doesn’t apply when it comes to a big, nameless, faceless corporation that might be killing hundreds of people. And I feel like that framing harms public understanding and societal response. And I just wonder what you think about media’s role in all of this.

Guardian (9/28/22)

KH: Yes, I think that’s right, and I could give you a whole dissertation answer on this, but for my work, I work both internationally and in the US to support people who are speaking up about environmental issues. So this is a trend globally. If you’re a community member or an environmental activist who speaks up about environmental issues, that’s actually one of the most dangerous activities you can do in the world right now. Every year, hundreds of people are killed and assassinated for speaking up about environmental issues, and many of them are Indigenous people. It happened here.

In the United States, we fortunately don’t see as many direct assassinations of people who are speaking up. But what we do see is a phenomenon that we call criminalization, which includes SLAPP lawsuits, and that really exploits gray areas in the legal system, that allows the wealthy and powerful to weaponize the legal system and turn it into a vehicle for silencing their critics.

Often it’s not, as you say, written in the law that this is illegal. In a lot of cases, there are more and more anti-SLAPP laws in place, but not in North Dakota. And so that really makes it challenging to explain what’s happening. And I think, as you say, that’s also the challenge for journalists and media organizations that are reporting on these types of attacks.

JJ: Let me bring you back to the legal picture, because I know, as a lot of us know, that what we’re seeing right now is not new. It’s brazen, but it’s not new. It’s working from a template, or like a vision board, that folks have had for a while. And I know that a couple years back, you were working with Jamie Raskin, among others, on a legislative response to this tactic. Is that still a place to look? What do you think?

KH: Yes. So there’s several efforts underway, because there’s different types of tactics that are being used at different levels. But there is an effort in Congress, and it’s being led by congressman Jamie Raskin, most recently, congressman Kevin Kiley, who’s a Republican from California, and Sen. Ron Wyden. So they have most recently introduced bipartisan bills in the House, just Senator Wyden for now in the Senate. But that’s to add protections at the federal level to try to stop the use of SLAPP lawsuits. And that effort is continuing, and will hopefully continue on bipartisan support.

Guardian (2/20/25)

JJ: Let’s maybe close with Deepa Padmanabha, who is Greenpeace’s legal advisor. She said that this lawsuit, Energy Transfer v. Greenpeace, is trying to divide people. It’s not about the law, it’s about public information and public understanding. And she said:

Energy Transfer and the fossil fuel industry do not understand the difference between entities and movements. You can’t bankrupt the movement. You can’t silence the movement.

I find that powerful. We’re in a very scary time. Folks are looking to the law to save us in a place where the law can’t necessarily do that. But what are your thoughts, finally, about the importance of this case, and what you would hope journalism would do about it?

KH: I think this case is important for Greenpeace, obviously, but as Deepa said, this is important for environmental justice movements, and social justice movements more broadly. And I agree with what she said very strongly. Both Greenpeace and EarthRights, where I work, are part of a nationwide coalition called Protect the Protest that was created to help respond to these types of threats that are emerging all over the country. And our mantra is, if you come after one of us, you come after all of us.

I think, no matter the outcome of this trial, one of the results will be that there will be a movement that is responding to what happens, continuing to work to hold the fossil fuel industry accountable, and also to put a spotlight on Energy Transfer and its record, and how it’s relating and engaging with the communities where it tries to operate.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with Kirk Herbertson. He’s US director for advocacy and campaigns at EarthRights International. They’re online at EarthRights.org. Thank you so much, Kirk Herbertson, for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

KH: Thank you so much.

This post was originally published on FAIR.