When war broke out in Europe in early August of 1914, that month’s edition of The Etude, America’s “Journal of the Musician, the Music Student and all Music Lovers,” had already appeared. The editor, James Francis Cooke, who had been at the magazine’s helm since 1908 and would remain there until 1949, first addressed the conflict in the September issue in an editorial rich with his characteristically WASPy sanctimoniousness: “War, always hideous, is never worse than when the people of so-called Christian and civilized nations fight,” he began. It would seem that infidels are allowed, indeed encouraged, to kill each other or should let themselves be killed by the forces of righteousness.

Cooke goes on to lament the increasingly efficient barbarity of mechanized modern warfare: “Not since men first chose to settle their disputes by swinging broad axes at each other has the machinery of battle been so horrible as now.”

Advances in technology were relentlessly retailed in The Etude. The journal was full of advertisements and articles about engineering innovations in the music industry. In 1914 these included hearing aids for piano tuners; portable practice keyboards; new-fangled electric lamps to illuminate all that sheet music printed in the magazine’s pages; various metronome models; and that industrious cousin to the musical keys, the typewriter. By 1914 this ever more reliable, refined, and rapid tool of commerce and communication had, readers were told, lightning-fast actions to match those of all those uprights and grands touted in the journal. The legions of typists, their fingers trained in childhood at the piano, were mostly women, who also comprised the main readership of The Etude. The magazine was abundantly graced by advertisements for skin creams and corsets.

Cooke claimed musical technology and tuition as forces for peace and prosperity. Yet his editorial is both ardently isolationist and vigorously opportunistic: “It is a fact that the triumphs of battle do not go to those who fight, but to those who are at peace. The neutral, non-fighting nation is always the real victor … Unwanted, unsought, great gains are bound to come to us.” His lofty anti-war pronouncements quickly give way to visions of a rising Musical Superpower: “With out vast territory, bursting granaries, enormous wealth, earnest workers and spirit of confident optimism, America should furnish opportunities so great that even the wildest imaginations might have difficulty in grasping them.”

In his editorial for the magazine’s next issue in October of 1914, Cooke conjured this destiny even more vividly: “Staggered by the misfortunes of Europe we must take the lot that fate has cast upon us. Tomorrow in America may be the dream of the ages. In music, as in all other arts, we are on the threshold of greatness which should thrill all those who love the name of the land of the free.”

Still at his post when, thirty-five years later, a second World War broke out in Europe, Cooke cited his predictions from 1914 in his editorial of October of 1939: “Through events entirely beyond our control, our musical interests in America, educational, professional and industrial, were compelled to advance in the years succeeding the great war and were benefited more than during the entire preceding century.” Just as Cooke had forecast back in 1914, the United States had indeed become “the most eminent musical center of all history.”

But Cooke had to tread carefully. The Etude had undeniably Germanic roots. It had been founded by Theodore Presser, the child of German immigrants. Needing compositions to complement the articles, the magazine began printing sheet music; the Presser firm remains the oldest continuously operating music publishing house in the United States.

When each of the century’s world wars broke out, Cooke used his editorials to recall that Presser’s father had spoken not just German, but French as well. Cooke also reminded readers that while Presser, who died in 1925, loved the music of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, he also harbored an intense hatred of German militarism. A long-time piano teacher and choral conductor, Cooke himself had studied in Wurzburg, before taking his Ph.D. back in the United States.

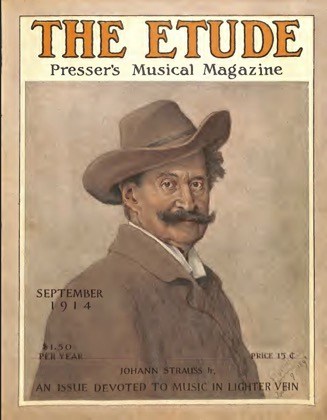

Balanced precariously between pathos and patriotism, the wartime pages of The Etude bristle with the tension between isolationism and empathy, pacificist bromides and calls for profit-making. Aside from Cooke’s condemnation of war, the September 1914 edition was an etude in escapism: “A Special Issue Devoted to Music in Lighter Vein,” that description running below the cover’s portrait of Johann Strauss, Jr. (In this image, Strauss could almost be an American sheriff in his cowboy and duster, and styled with Wild West moustache.) Yet the Waltz King of Blue Danube fame was also the composer of the Radetzky March, the ubiquitous theme song of the Austro-Hungarian army. An article in The Etude of Octboer of 1914, “The Music of the Warring Nations” extolled the heroic qualities of the combatant countries’ military hymns: France and Belgium, England, and ”Slav” (i.e., Russia) all have their nobel calls-to-arms. But at the top of the list came Germany and Austria, and the Radetzky March gets it due for inspiring the polyglot peoples of the Hapsburg Empire to fight: “The Hungarians are excellent soldiers and especially susceptible to the appeal of their inspiring national hymn.”

When America entered the conflict 1917, Cooke duly added his rhetorical firepower to the cause while also enlisting the propagandistic talents of his art department

As Cooke had hoped, The Etude emerged ascendant from the Great War. “Presser’s Musical Magazine” reached the apogee of its circulation at 250,000 in 1919. A decade later, when the Great Depression put an end to the editor’s fantasies of perpetual expansion, the magazine was making a loss and did so continuously until it was shuttered in 1954, five years after Cooke’s long editorial tenure had ended and six years before his death. By then, the journal’s print run had fallen to nearly 50,000.

Across these decades of growth and decline, The Etude shows that Americans, from Pentagon first desk to piano stool, have been adept at finding ways—commercially, industrially, musically and morally—of profiting from foreign wars while singing and playing of liberty and freedom, peace and power.

The post Over There: Isolating War Music appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.