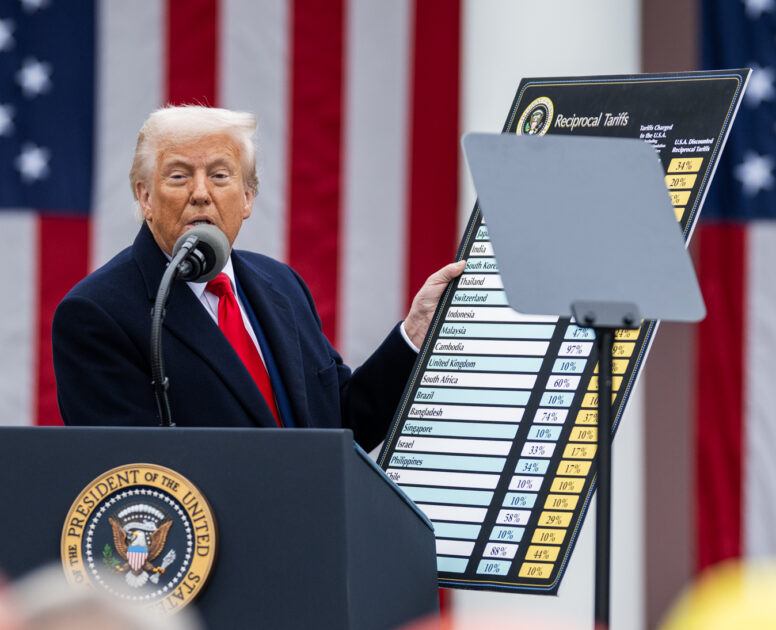

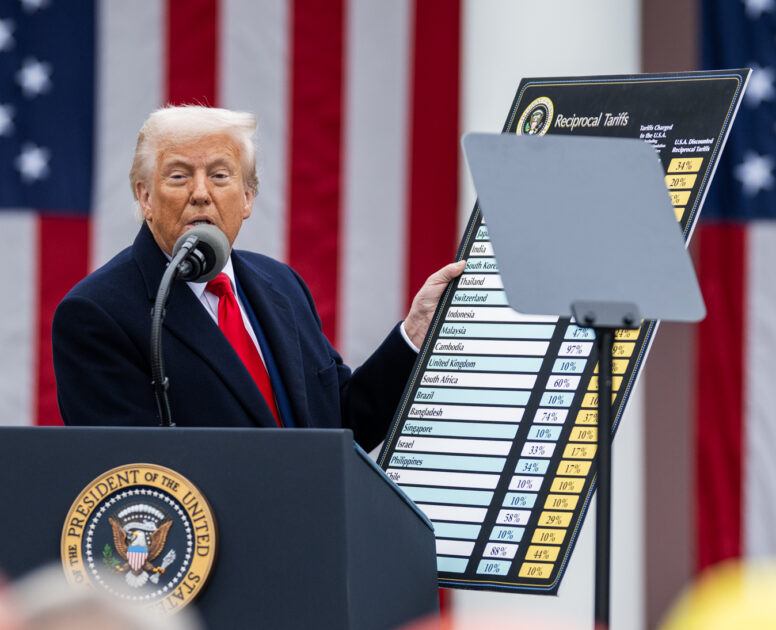

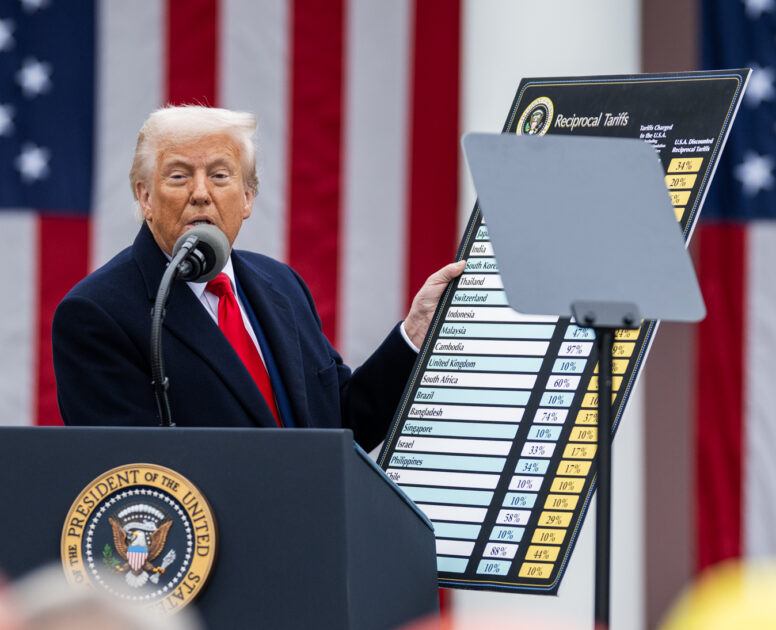

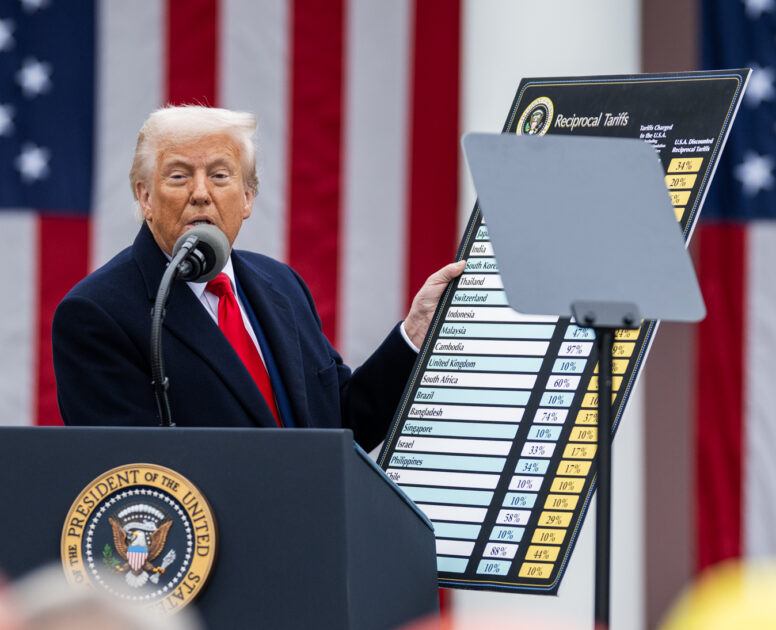

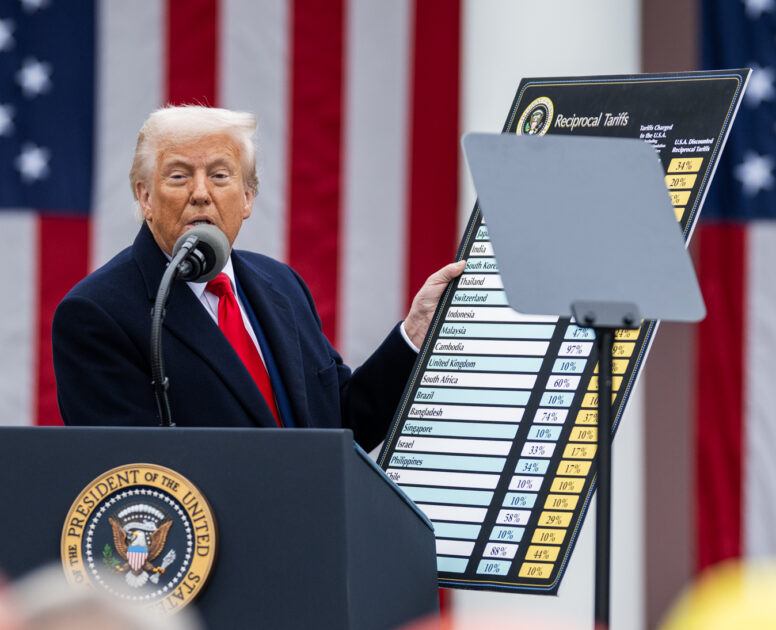

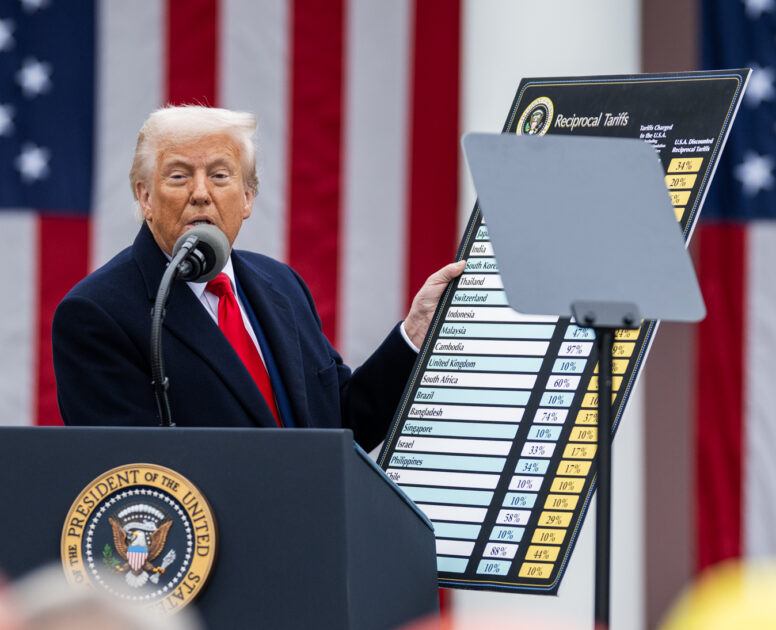

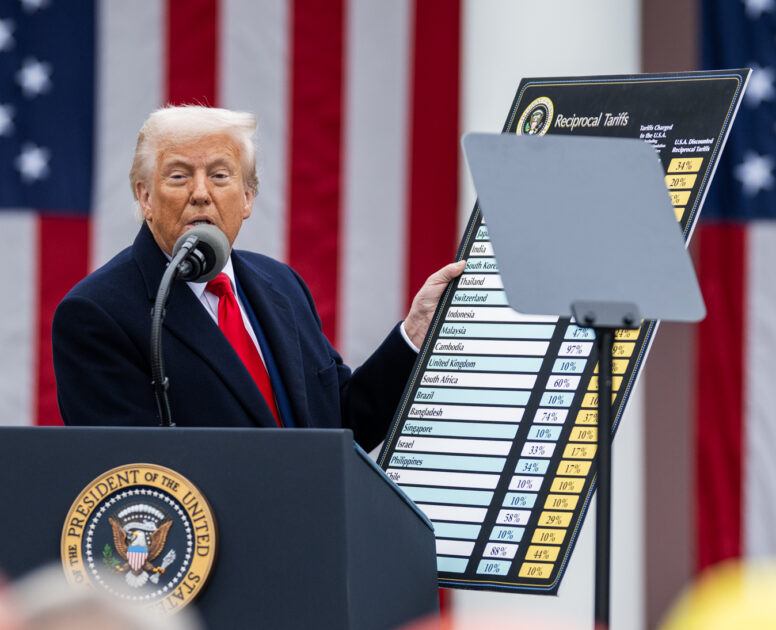

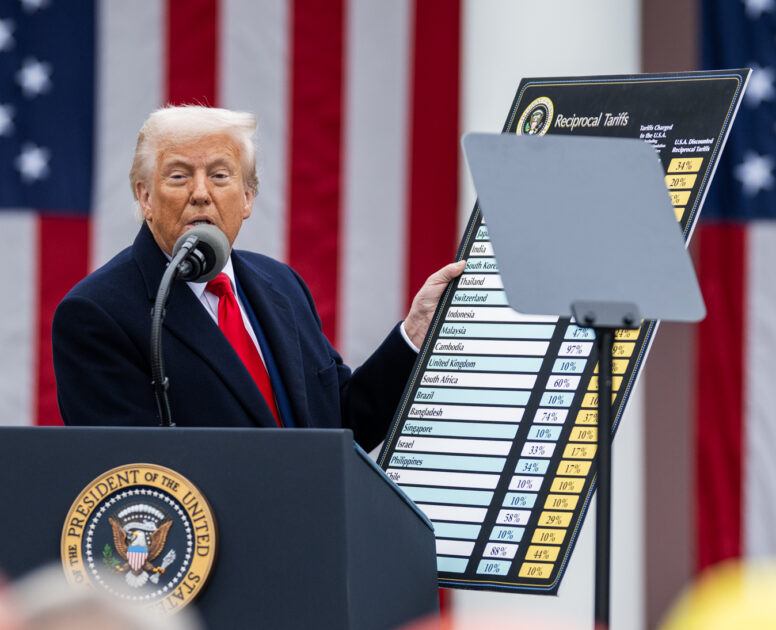

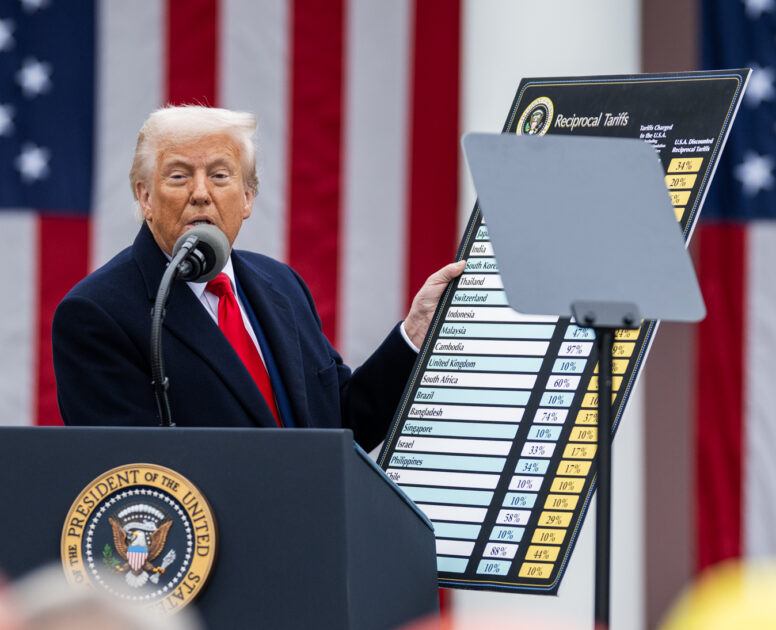

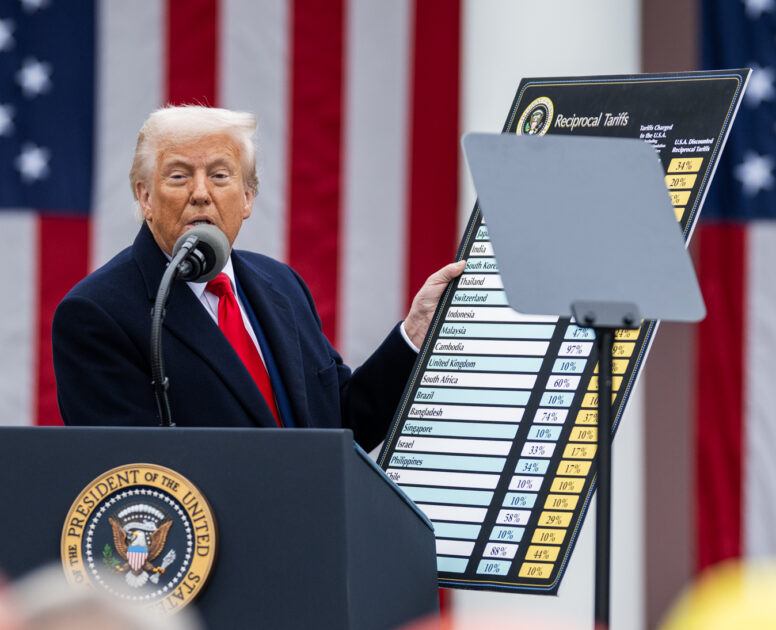

Photograph Source: The White House – Public Domain

Some years back, when Obama was trying to push through the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), I was giving a talk on the tentative deal and arguing it was not a good deal. My main objections were to the provisions on patents and other intellectual property issues, but I also felt that its rules on digital commerce appeared to be designed to protect Amazon and Facebook and other Internet behemoths.

While I mostly had a friendly audience, there was a woman from Vietnam who strongly disagreed. She said that her native country stood to have large gains from the TPP and felt it would be a real loss to it if the deal did not go through.

I had to admit that I was not familiar with how the deal would affect Vietnam. I did know the projections, even from supporters of the deal, showed modest gains for the United States, Japan, and most of the other countries in the pact, but I did not know what they showed for Vietnam. I told her I would check on this and get back to her.

When I checked on the projections of gains for Vietnam, I found out that she was correct. They showed very substantial gains for the country. These gains were an order of magnitude larger than the gains projected for the other countries in the pact.

But the reason for Vietnam’s large projected gains had relatively little to do with commitments from the other countries in the TPP. The reason that Vietnam was projected to have large gains is that, unlike the other countries in the TPP, it still had very high tariffs on imports.

The TPP required Vietnam to lower its tariffs against the other countries to near zero. This was why it was projected to have large gains from the TPP.

Of course, Vietnam could lower its own tariffs any day of the week. It did not need the TPP to make this call, although there could be political factors that would make it easier for its government to lower tariffs in the context of a trade deal than would otherwise be the case.

But the point here is that tariffs are a tax that a country imposes on itself. It imposes costs in the same way that a tax on gas or beef imposes costs. Tariffs can also harm trading partners, but that doesn’t change the fact that the main victim is generally the country imposing tariffs.

This is an important point to keep in mind when we evaluate whatever concept of a trade deal with China that Treasury Secretary Bessent puts forward. If we end up with a lower tariff on most items than the 154 percent tax that Trump has currently imposed, this will be good news. If we still end up with a high tariff, which seems likely, that will not be something to celebrate even if our tariff on Chinese products ends up being higher than China’s tariffs on our products.

It is also important to always remember to keep your eyes on the ball. The Trump administration constantly spews total nonsense on just about everything. Last week Attorney General Pam Bondi said that Trump saved between one-third and two-thirds of the country from dying from fentanyl overdoses in his first hundred days in office. She still has not acknowledged this was a mistake.

Anyhow, Trump has invented a national emergency out of thin air on our trade deficit. There is literally no obvious problem in the deficit. There are issues that we can and should be negotiating with China, but insofar as there is some sort of crisis stemming from our trade with China and other countries, it is entirely Trump’s own creation.

This first appeared on Dean Baker’s Beat the Press blog.

The post Tariffs Are Taxes on Us, Not Them appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.