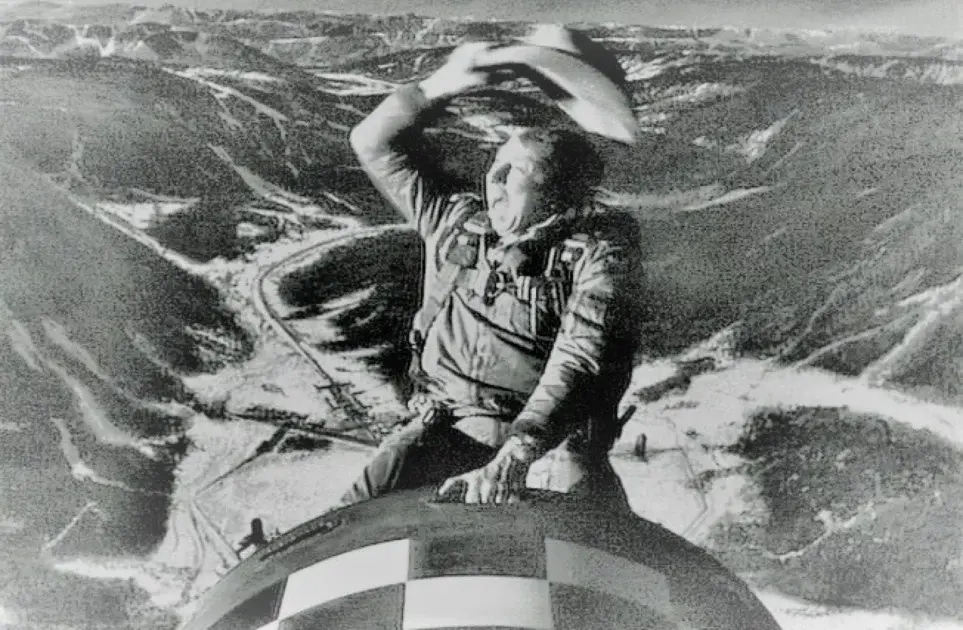

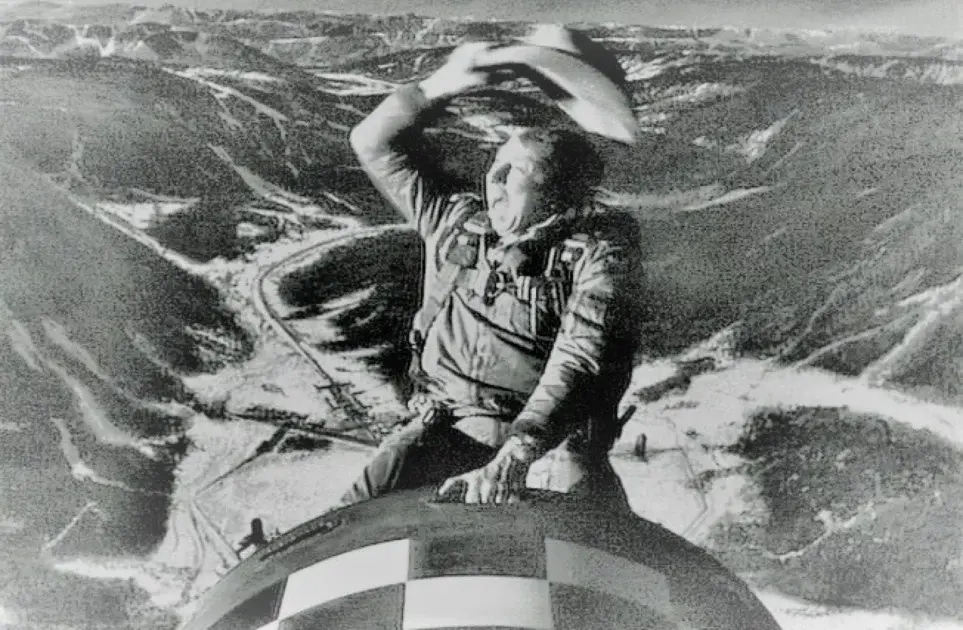

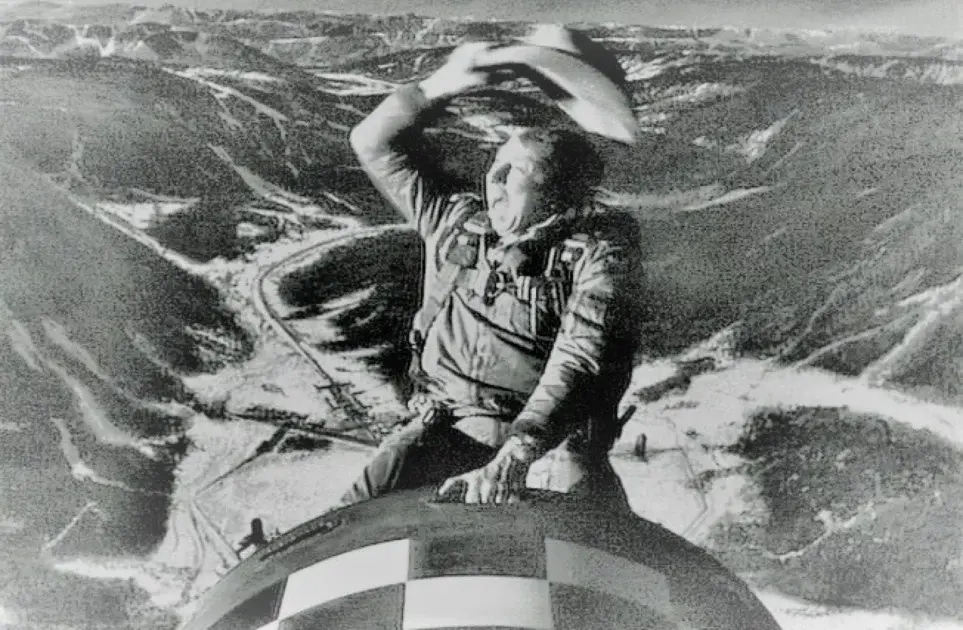

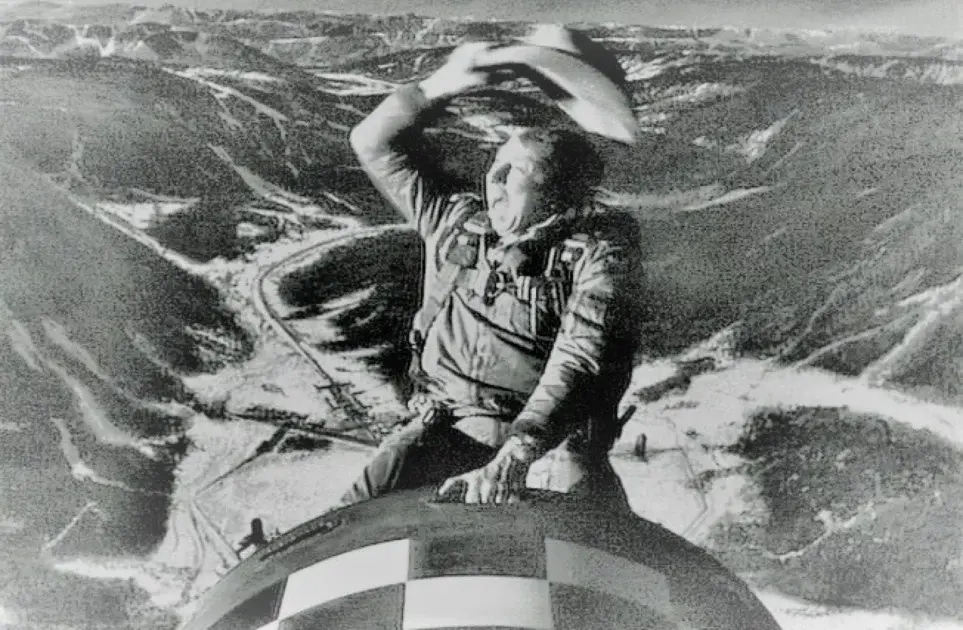

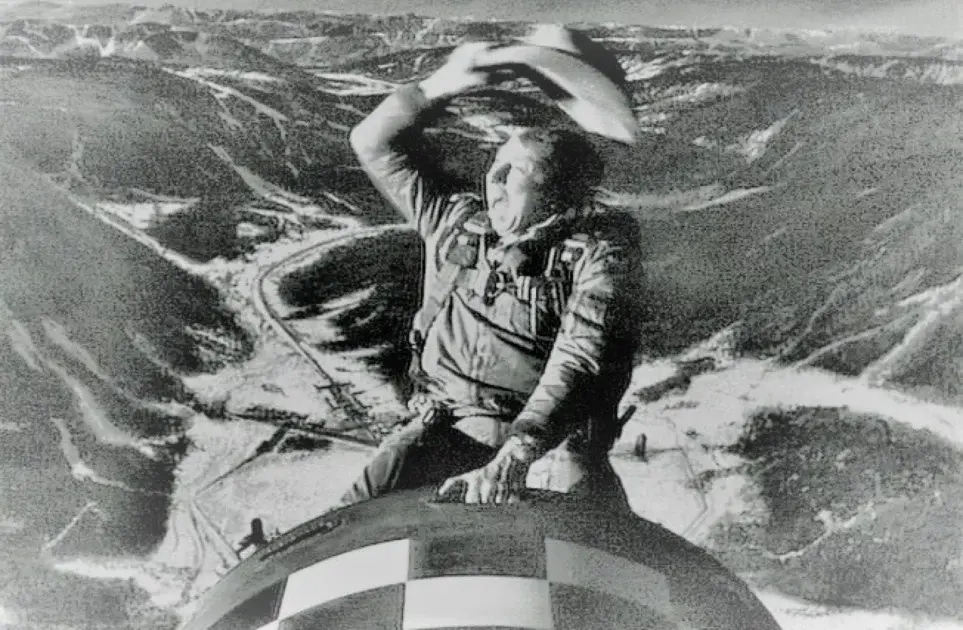

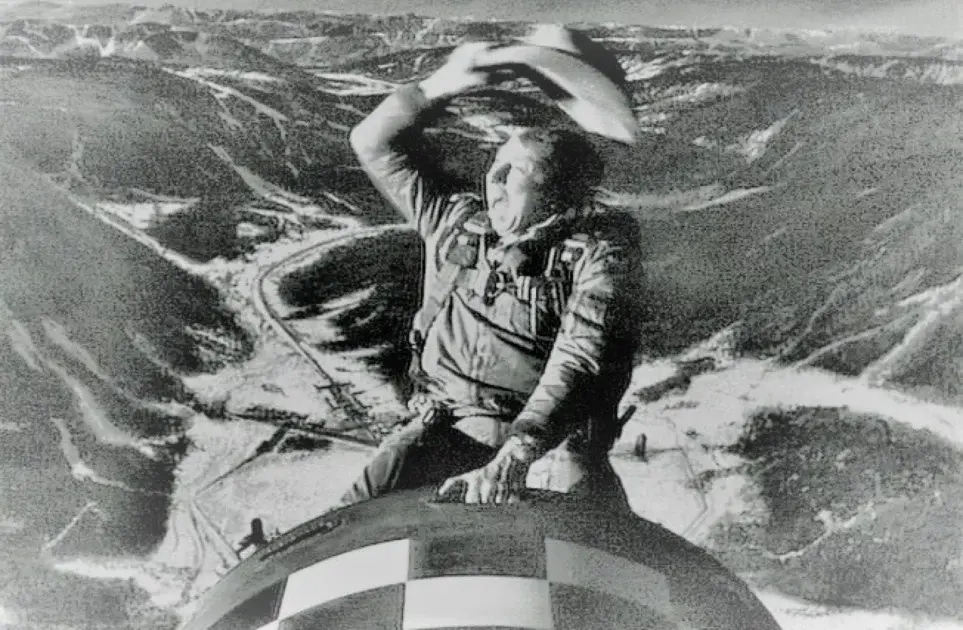

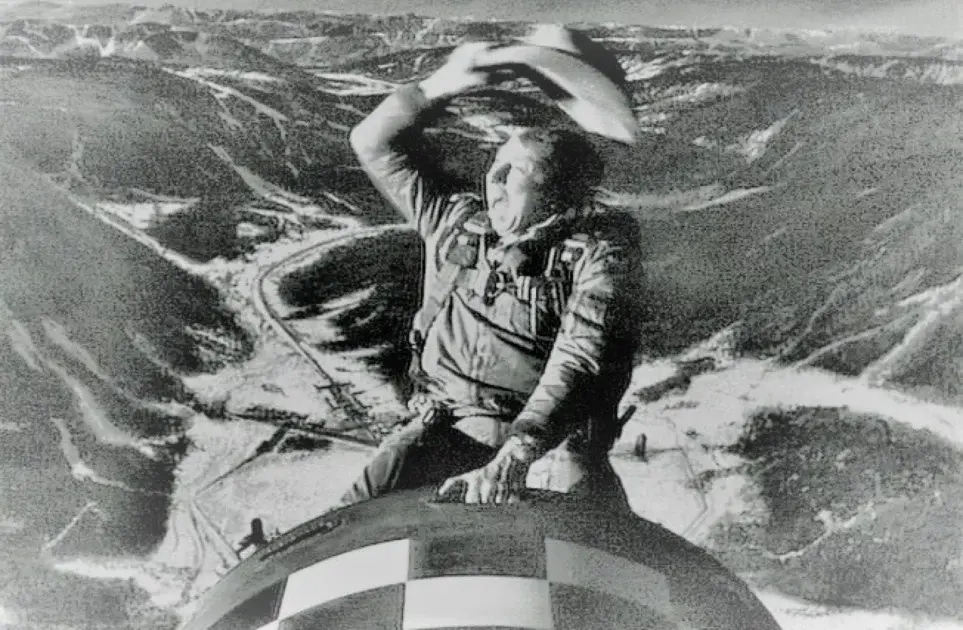

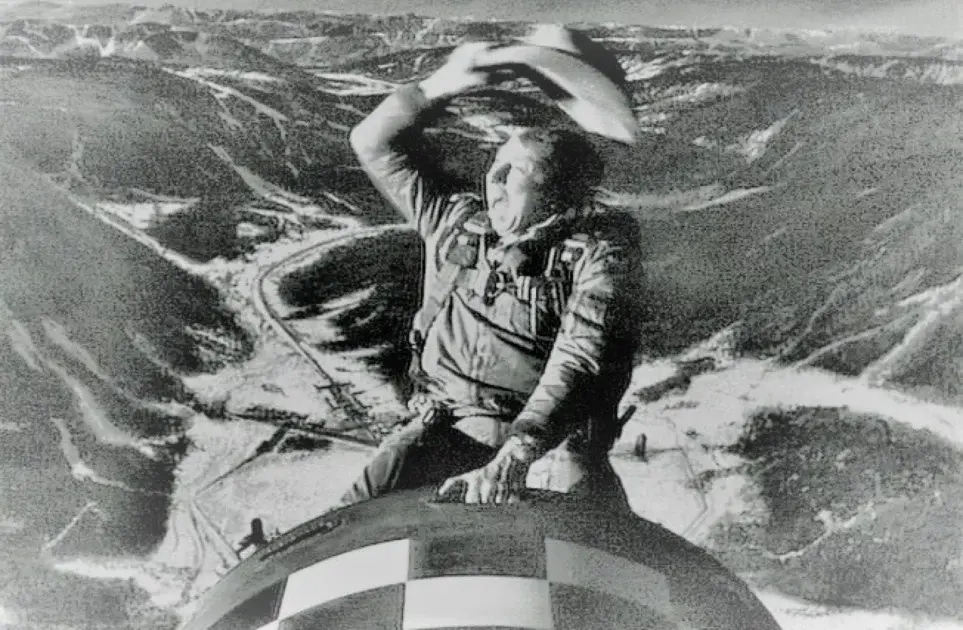

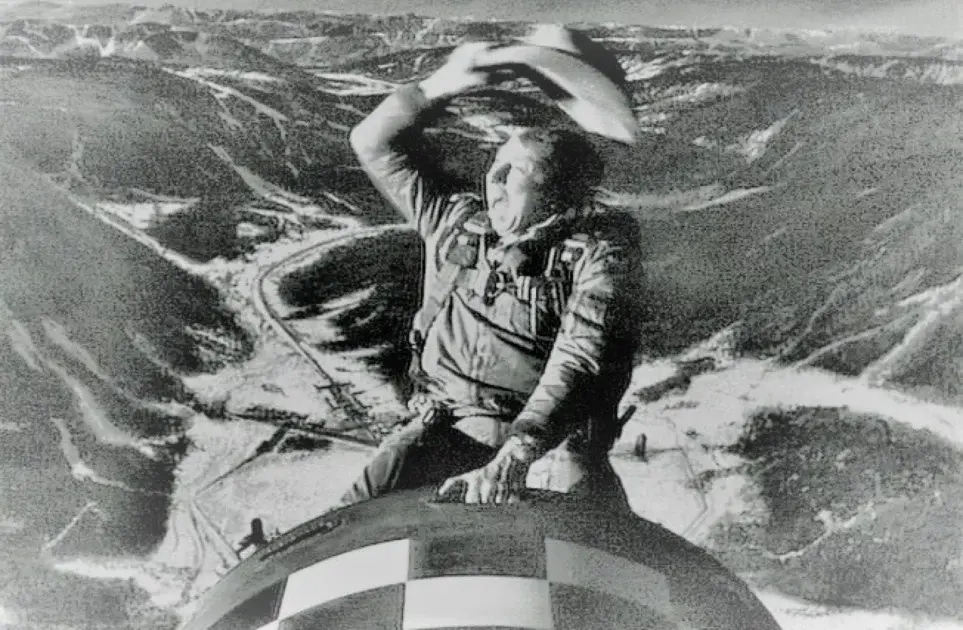

Slim Pickens (Louis Burton Lindley Jr.) in “Doctor Strangelove.” Pickens was a San Joaquin Valley native, born in Kingsburg, 1919, died of a brain tumor in Modesto, 1983.

I had just come back from a demonstration against a uranium mine near the rim of the Grand Canyon and talking to Native people from several tribes whose water, air and land would probably be polluted by the mine, the trucking, and the mill. Their struggle to protect their homes reminded me of my hometown, Modesto, only 50 miles from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and 35 miles from LLNL’s Site 300 High Explosives Testing Range.

None of us knew the dangers on the Colorado Plateau or in the north San Joaquin Valley or in the valleys around Livermore. In the 1950s, in the San Joaquin Valley we were using smudge pots to fight frost in the peaches and almonds. We had a bad polio epidemic in 1953 just before the Salk Vaccine came out and ended polio here. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring didn’t come out until 1962, and DDT was the best pesticide ever made: “It kills everything for 28 days,” the farmers said. Many of us got Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis) and still have to explain the lung scar to physicians far from agricultural areas. Occasionally the newspaper would announce a new case of Bubonic Plague in the Sierra Foothills. And, from the middle of WWII until the 1990s, we had our own (conventional) arms-manufacturing and storage facility 5 miles east of Modesto called Norris-Thermador, which employed up to 3,500 people when in operation but was best known for its long layoffs.

We had no idea that during those years over on the Colorado Plateau Navajo miners were working in unventilated uranium mines during the great uranium boom of the 1950s and the Navajo Nation still suffers from radioactive mine litter, waste and dust.

We knew nuclear bombs were being tested in Nevada near Las Vegas and on islands far away in the Pacific Ocean. We had no idea in high school in the middle of the Cold War that the bombs were being designed and developed 50 miles away from us. LLNL was shrouded in secrecy in those years. But after Sputnik at the start of my sophomore year, a lot of us were subjected to the awkward attempts of our excellent chemistry teacher to teach us physics. Nevertheless, we were nearly completely ignorant of the greatest environmental threat in our vicinity. But a few years later we learned an ominous new term describing several nearby locations: cancer clusters.

Analysis contained in an Environmental Impact Statement in accordance with the National Environmental Protection Act states that the effects of an accident at LLNL would spread 50 miles, as far north as Marin County, through San Francisco, the Peninsula, as far south as San Jose, and as far east as Tracy, Stockton, and Modesto. As many as 7 million people would be affected by plumes of either radioactive or chemically toxic particles. From an environmental safety standpoint it doesn’t make any sense for 90,000 people to live in Livermore, but many work at the lab, which has grown to completely fill its one square mile campus, and the Silicon Valley “high-tech/bio-tech engine for growth” employs many more. Tens of thousands of other workers commute daily across the 10-lane Altamont Pass (I-580) from cities in the northern San Joaquin Valley to jobs in the lab and other high-tech industries. Median home price in Tracy, at the eastern foot of the Altamont was $680,000 last month; in Livermore, on the western side of the pass, median price is $1.1 million.

All the energy, ambition, and traffic generated by high tech and nuclear weapons remind me of lines from Mandeville’s “The Grumbling Hive,” 1705:

A Spacious Hive well stock’d with Bees,

That lived in Luxury and Ease;

And yet as fam’d for Laws and Arms,

As yielding large and early Swarms;

Was counted the great Nursery

Of Sciences and Industry.

The National Nuclear Security Administration, a division of the Department of Energy, has stated that LLNL, because of special circumstances, cannot be made safe. One glaring special circumstance is that LLNL is only one square mile in size and surrounded by suburban housing. By contrast, Los Alamos National Laboratory is 40 square miles, Hanford Site is 586 square miles, the Savannah River Site is 310 square miles, and LLNL’s Site 300 is 11 square miles.

In the early 2000s, LLNL in collaboration with Russian nuclear scientists, created Livermorium, a highly radioactive element, Lv, 116 on the Periodic Table. The City of Livermore changed its seal so that the graphic of an atom erases large parts of a cowboy on a bronc and a vineyard. And it created Livermorium Plaza with a large round statue of Lv at its center.

I found the best way to begin to get an idea of what TriValleyCAREs is and does is to compare its mission statements with the statements of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory:

For over 70 years, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) has applied science and technology to make the world a safer place.

The Lab’s mission is to enable U.S. security and global stability and resilience by empowering multidisciplinary teams to pursue bold and innovative science and technology.

Mission Areas

Enhancing and expanding our mission in the broad national security space.

By splitting our broad and evolving mission into four areas relevant to the current and future stability of our world, we’re better able to address issues of nuclear deterrence, threat preparedness and response, climate and energy security and multi-domain deterrence. We count on our talented workforce to think bigger in all four areas of our central mission. With exceptional work in preeminent areas of science and operations, the Lab’s influence doesn’t stop at our country’s borders — our innovations make the world a better place to live…

This statement brought to my mind former Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall’s comment:

Although many disclosures did not surprise me, I concluded that the Cold War had been an incubator of deceitful practices and harmful illusions, and that if one was to gain a clear picture of this period of our history, it was essential to distinguish myths from truths.”

– Stewart Udall, The Myths of August, p. 21, 1994. (Udall spent much of his post-government years trying to get justice for miners and down-wind residents from the harm to health and livelihood from uranium poisoning and nuclear tests on the Nevada desert.)

TVC’s mission statement struck me as a vision of peace more important for us to hear today than it was 40 years ago, when the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Doomsday Clock registered four minutes instead of this year’s prediction of 98 seconds:

Tri-Valley CAREs’ overarching mission is to promote peace, justice and a healthy environment by pursuing the following five interrelated goals:

1. Convert Livermore Lab from nuclear weapons development and testing to socially beneficial, environmentally sound research.

2. End all nuclear weapons development and testing in the United States.

3. Abolish nuclear weapons worldwide, and achieve an equitable, successful non-proliferation regime.

4. Promote forthright communication and democratic decision-making in public policy on nuclear weapons and related environmental issues, locally, nationally and globally.

5. Clean up the radioactive and toxic pollution emanating from the Livermore Lab and reduce the Lab’s environmental and health hazards…

Tri-Valley CAREs was founded in 1983 in Livermore, California by concerned neighbors living around the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, one of two locations where all US nuclear weapons are designed. Tri-Valley CAREs monitors nuclear weapons and environmental clean-up activities throughout the US nuclear weapons complex, with a special focus on Livermore Lab and the surrounding communities.

This statement has the clarity of Annie Jacobsen’s comment in her 2024 best-seller, Nuclear War: A Scenario: “It was the nuclear weapons that were the enemy of all of us. All along.”

And it is as simple as what Albert Camus wrote two days after the US dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima:

…mechanistic civilization has come to its final phase of savagery. A choice must be made, in the fairly near future, between collective suicide or the intelligent use of scientific conquests… (Combat, Aug. 8, 1945. )

Sitting at the edge of Silicon Valley, the latest manifestation of “mechanistic civilization,” LLNL represents the apex of Western technology: the design and development of nuclear weapons. Palo Alto based Hewlett-Packard’s “El Capitan,” the world’s most powerful computer, is lodged at LLNL, to advance nuclear weapon science. A private/public partnership of University of California, Bechtel, BWX Technologies, Amentum, and Battelle Memorial Institute affiliated with Texas A&M University, called Livermore National Security, LLC, manages LLNL.

Camus’s suicide comment is not an existential anachronism: according to the Union of Concerned Scientists we are closer than we have ever been to nuclear apocalypse.

Driving into Livermore Valley to meet TVCs staff, I couldn’t help remembering one stormy day when I was 10 or 11 years old and across the freeway from LLNL was entirely green pasture and I saw several black and bay horses, manes and tails flying as they played in the wind. But we aren’t horses and neither science nor technology offer us guidance about what to do about nuclear weapons.

Scott Yundt, TVCs director, met me in the lobby of a plain, two-story office in downtown Livermore and took me up to a lovely office – lovely because it had no pretense or décor, just the slightly untidy air of a place where a lot of good work had been done for a long time—some posters from past actions on the walls, computers on several desks, enough chairs and long tables for meeting purposes, racks for documents and cabinets along the walls. And that was about as far as I ever got on my idea of doing a profile on TVC because Yundt immediately directed my attention to the Lab and kept me focused for the entire interview. He left to doubt that for him legal action was what to do about nuclear weapons.

“We are entering a new nuclear arms race,” he told me. “It’s visible in LLNL’s new 15-year plan, which calls for tearing down old buildings and replacing them with 70 new ones, mainly devoted to nuclear work,” he said. “And in the last two years, employees have increased from 7,000 to 9,500.” LLNL announced in 2015-16 a 10-fold increase in the number of test explosions. It was rushed through NEPA.

Yundt was working for an Oakland environmental law firm on TVC cases and decided to go full time with TVC in 2009 as its staff attorney drafting federal Freedom of Information and state Public Records Act requests, writing environmental statement comment letters, representing workers exposed to radiation considered “an externality of nuclear weapons program,” he said. The federal government has a program, the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program (EEOICP), just for people employed at 115 Department of Energy sites: Hanford, Los Alamos, LLNL, Rocky Flats, plus little contractors. The programs are both for uranium radiation and toxic chemical exposure. More than LLNL 3,000 employees have made claims plus 81,000 nationwide, minus military personnel who have handled radioactive material. “The government has spent billions,” Yundt said.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency has found that LLNL is a toxic Superfund site, but Yundt said that EPA figures “it would take between 70 years and infinity,” for cleaning it up. Some of the pollution, he added, was generated by a WWII U.S. Naval Air Station located on the LLNL site, which contaminated the area with jet fuel and solvents.

Since the 1960s, TVC has found through data searches that Livermore Lab has released 1 million curies of radiation into the environment, approximately equal to the amount of radiation deposited by the US bombing of Hiroshima. Approximately three-quarters of a million curies have been tritium, Yundt explained.

LLNL opened Site 300 in 1955 as a “high explosives testing area” on seasonal pastureland. It is located on Corral Hollow Road just beyond the western limits of the City of Tracy, in the San Joaquin Valley. LLNL tests its proprietary nuclear warhead triggers on the site. Instead of plutonium in the experimental warheads, LLNL uses depleted uranium in its tests of different mixtures of explosive triggers. This is an air-quality issue for the people and livestock in the northern San Joaquin Valley. This program adds PM 2.5 particulates to the San Joaquin Valley’s air pollution, but this particulate “is a real special dust,” Yundt said. TVC went to state/fed air-quality-board hearings with 80 people. The local air pollution control district issued a letter instead of rubber stamping the LLNL program. But LLNL management never replied — one more example in this region of how “national security” equals local insecurity.

The Tracy city limits did not expand west of I-580 until persuaded by the developers of Tracy Hills, AKT Development, founded by Angelo Tsakopoulos and managed at the time by his daughter, now California Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis. Yundt said Tracy Hills, now operated by partial owners, Lennar Homes, was planning a senior facility on the fence line between its property and LLNL’s Site 300. I thought that plan showed a remarkable capacity for denial, even for California developers.

LLNL is building up – new buildings, more employees, more explosive tests – because the Department of Energy/National Nuclear Security Administration, and the Department of Defense are funding design and development of two new warheads using plutonium pits, the terrestrial warhead called the W87-1 and a submarine warhead to be called the W93.

There is a Level 3 Biowarfare Laboratory at the LLNL main site in Livermore. A level 3 lab typically contains “microbes that are either indigenous or exotic and can cause serious or potentially lethal disease through inhalation” like Anthrax, COVID-19, Hantavirus, Malaria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Rift Valley fever, Rockey Mountain spotted fever, West Nile virus, and Yellow fever.

TVC sued the LLNL because the environmental impact statement included no analysis for terrorism. Yundt said that the LLNL reply was inadequate because it didn’t deal with intentional acts, replying only that the probability of a successful attack was low because LLNL was a “high security site.”

But the issues of management and “high security” at LLNL are closely connected and have had quite a history in recent years, which will be treated at the top of the second installment on the history of the relationship of TVC and LLNL.

The post National Security is often Local Insecurity: TriValley CAREs and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.