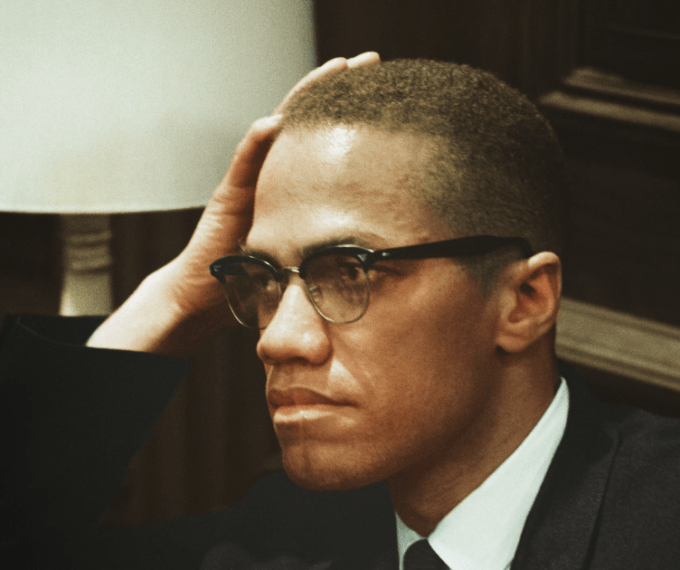

Image by Unseen Histories.

Malcolm X (born: Malcolm Little) would have been 100 years old on May 19 2025, a century on from his birth and 60 years after his martyrdom it’s interesting to reflect on what consistent principles he advocated and organised around, and how his life work helps us to understand the global situation today. Malcolm X towers amongst some of the greatest figures of anti-colonial resistance in the context of the USA and further afield, but like all historical revolutionary figures their legacy is defanged and turned into something safer and more acceptable to the colonial society which is adept at assimilation, a framework of assimilation that actually Malcolm X always countered and railed against.

In the late 19th century and into the 20th century often family networks became committed to anti-colonial activism and resistance, and this carries on through a few generations as is the case with the Littles. Many members of Malcolm X’s family always directly communicated to him and encouraged his commitment to revolutionary lives, his brother’s wrote to him while he was in prison encouraging him to join the Nation of Islam of which they were already committed members. Malcolm X expressed great admiration for his sister Ella Collins, who he considered one of the most inspirational people in his life.

Revolutionary Family, martyrdom and co-option of Malcolm X

Malcolm X (Malcolm Little) was born into a social context in which he, like many of his siblings and close family members were brought into the struggle against colonialism and racism. His mother was born in Grenada in the late 1890s and was the child of Nigerians who were enslaved by the European colonialists. Louise Little herself was introduced into Marcus Garvey’s Pan-Africanist United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) by an uncle after she moved to the USA circa 1917. Louise Little could ‘pass’ as white, and it was said that it was a rape of her ancestors by european colonalialists that was the cause of her light-skin, which then was the reason why Malcolm X himself was so light and red-haired, something which Malcolm X references in his self-named ‘Detriot Red’ at one point in his younger life.

Backgrounds of colonial oppression and how they literally shape us must have weighed-down on Malcolm X. Malcolm said that his father was most likely killed by racists, and it was this work of his father that he so greatly admired. Malcolm X’s father Earl Little was a committed activist of the UNIA, and often took along Malcolm X in his political work: “the image of him that made me proudest was his crusading and militant campaigning with the words of Marcus Garvey … it was only me that he sometimes took with him to the Garvey U.N.I.A. meetings which he held quietly in different people’s homes.”

It’s important to remember the generational contexts, the global and local contexts to this relative growing upsurge through the first 70 years of the 20th century. Veteran Black / Pan-Africanist revolutionary Bob Brown’s February 2022 interview on Black Power brilliantly outlines these dynamics employing an inter-generational understanding on the timeline. It is also a social pattern that families who have considerable members in anti-colonial struggle which then, as with the general global trend and changing balance of forces, start to break-up and fall into assimilation of all sorts. And that is also the case with Malcolm X, after his martyrdom there is a multifaceted concerted campaign to turn him into a relatively harmless figure. In actual fact, this starts during his own lifetime when Republican Party supporter Alex Haley framed Malcolm’s life in the ‘autobiography’.

Similarly. Spike Lee’s 1992 Malcolm X film which basically couldn’t get the budget unless major radical aspects of Malcolm’s life were erased such as his visits to Ghana, Egypt and Gaza, his close comradeship with Adburahman Babu and his advocacy for anti-British revolutionary movements such as the Land and Freedom Party in Kenya or ‘Mau Mau’. Indeed, the film fails to show that Malcolm X visited Egypt in 1959 as an NoI ambassador to the revolutionary Gamal Abdel Nasser (see Marika Sherwood’s 2011, Malcolm X’s Visits Abroad). Despite Malcolm stating that his sister was a leading influence and support in his life, Ella Collins is not mentioned at all in the film.

It might be useful to reflect on the family and generational nature of those in the anti-colonial movement, as it is a legacy that by itself speaks to us that we should continue to follow in that path of struggle and it is arguably the antidote to the appropriation of Malcolm X and others into race-class interests of the colonialists today.

On African-Asian Unity

“The red, the brown and the yellow are indeed all part of the black nation.” – Malcolm X, 1963.

Malcolm X developed his framework of anti-colonial unity of all non-white people in his construction of the ‘Black Revolution’ in large part out of the Nation of Islam’s concept of black unity and internationalism, which itself was a reflection of the radical dynamic of its time. It’s especially in the context of the Caribbean, East Africa, South Africa and England that the colonialist is committed to and has been largely successful in ensuring two major groups of colonised peoples don’t unite against the common oppressor – African and Asian peoples. Despite general successes in this divide-and-rule, there have been moments of unity in these regards and advocates for that include Dedan Kimaathi (who worked directly with the writer’s paternal grandfather – Gopal Singh Chandan – in Nairobi against the British), Steve Biko and Walter Rodney who argued that Asians must be included in Black Power / Black Consciousness and united black resistance. Malcolm X explicitly argued the same and outlined this in one of his most important speeches Message to the Grassroots, December 10 to quote:

“In Bandung back in, I think, 1954, was the first unity meeting in centuries of black people … At Bandung all the nations came together. There were dark nations from Africa and Asia. … The same man that was colonizing our people in Kenya was colonizing our people in the Congo. The same one in the Congo was colonizing our people in South Africa, and in Southern Rhodesia, and in Burma, and in India, and in Afghanistan, and in Pakistan. They realized all over the world where the dark man was being oppressed, he was being oppressed by the white man; where the dark man was being exploited, he was being exploited by the white man. So they got together under this basis — that they had a common enemy.”

We live in an era where these advocates for anti-colonial African-Asian unity are in tatters, communities are increasingly internalising seemingly endless colonial divisions, and the white supremacist global surge has brought back the old racist tropes of all kinds and our children are playing it out from primary school age. One of the most graphic illustrations of Malcolm X’s work on uniting Asian and African people were his visits to England. On his visits Malcolm X was very comfortable and positive about being hosted by Pakistanis in the Student Islamic Societies, being hosted by Bengalis, and being hosted – just nine days before his martyrdom – jointly by Caribbean and Punjabi people in Smethwick where they were facing housing discrimination and racist attacks by the political class. The Smethwick trip led to Malcolm quipping: ‘let’s not wait for the gas chambers’. Malcolm X was very encouraging towards non-white/black unity of all African, Caribbean and Asian people in England: “West Indians in England, along with the African community, along with the Asians began to organise and and work in coordination with each other, in conjunction with each other. And this has posed a very serious problem.”

While Malcolm X was keen to engage the grassroots. – ie., people in actual colonised communities of the poor and oppressed, one has to also be vigilant to how other actors were pushing Malcolm X into more colonial spaces and places. One such moment that might need more critical research and reflection is how BBC-aligned Eric Abraham’s was the facilitator to Malcolm X’s speech to the Oxford Union. Abrahams would go on to support the USA invasion of Grenada against the revolutionary Maurice Bishop , amongst other questionable activities. Any leading radical anti-colonial figure will always see people encourage them into the colonial space away from the anti-colonial space. Ultimately, Malcolm X was martyred because he refused the co-option, and instead constantly re-affirmed his support to the most radical wings of the global struggle.

However encouraging Malcolm X was in this regards African-Asian Unity, it is a challenge that was never really developed and has fallen away to a point where the colonial state and its agents and minions are committed to putting a massive amount of hostility on anyone who is trying to build such unity. It seems many cannot just come to terms with nor accept that people like Biko, Walter Rodney and Malcolm X were so keen on unity between Africans, Caribbeans and Asians. This growing internalisation of colonial divisions is fused with growing far-aligned anti-migrant politics targeted on all non-white people, but with a strong current of Islamophobic and anti-Asian racism in that. Second, third, and fourth generation non-white people residing in the colonial centre have successfully been recruited into viciously scapegoating new non-white working class migrants, which speaks to just such divisive colonial successes.

The successes of this new colonial assimilation of non-white people against other non-white people has become so normalised that non-white people will frequently, confidently and casually raise old racist tropes and lies about new migrants ‘culturally despoiling this country’, and ‘taking away our housing’ etc. Perhaps the Malcolm X of the mid 1960s would return if he would pour ire on these new colonial sell-outs.

Malcolm X himself railed against western arrogance and nationalisms, and instead promoted an anti-colonial liberation-oriented ‘nationalism’ of united colonised peoples resistance and total liberation. While we have the manifestation of the new colonial racism and anti-migrant politics in the examples such as ‘Foundational Black Americans’ (FBA) and ‘American Descendents Of Slaves’ (ADOS) in the USA context, Malcolm X instead argued that ‘we are not Americans but victims of Americanism’, something that can also equally be applied to Britishness. In their toxic and racist anti-migrant stances, would FBA/ADOS and similar crowds even accept Malcolm X with his Caribbean-born mother, as these circles are largely vested in targeting Caribbean migrants with their racism.

It was these colonial frameworks of ‘British Muslim, ‘British Asian, and ‘Black British’, that the colonial state has been developing since the 1960s, and today one has to admit that this is a largely successful project, in which hardly anyone in diasporic colonised communities are pushing back on this assimilation into British colonial identities. People have allowed themselves to be herded into a position where they think, to use Malcolm’s ‘house slave / field slave’ dichotomy, being handed down the slave-masters clothes and his leftovers is arriving in the land of milk and honey, and they all prey the master’s house – Britain and Britishness – isn’t burnt to the ground. Where are the militants of the ‘field’ that pray for a great wind to encourage the fire against the oppressors today? Pronouns? “Whenever the master said “we,” he said “we.” That’s how you can tell a house Negro.” – Malcolm X, 1963.

Supporting and raising global resistance

“We need a Mau Mau revolution in Mississippi, we need a Mau Mau revolution in Alabama, we need a Mau Mau revolution in Georgia, and we need a Mau Mau revolution in Harlem,” – Malcolm X

We live in a world where there is no actual socialist or radical anti-colonial politics, culture and leadership. That era is over. Today’s world is where toxicities of coloniality (far-right racist politics) are being normalised, much of this is done by the infrastructure of social media for decades now, which has been the leading tool to direct massive global communities into right-wing hegemony. The ‘BRICS’ formation also align with this new global fascist revolution with South Africa having the most anti-African immigration laws on the continent, India playing out the British colonial partition and thinking it is the Israel towards its own ‘Palestine’ that is Pakistan (the analogy is a nonsense for the most), and China but moreso Russia openly pushing the the most vicious far-right politics across the world, whose direct and indirect consequences across Africa and other regions of the world is more colonial extraction and looting and the massacres and rorutre and rape that has to be done to facilitate the exploitation of non-white peoples land and labour. Malcolm X was in militant counter-opposition to all of this.

Everywhere on the planet where it looked like the poorest and darkest were engaged in a total liberation war, Malcolm saw himself as in union with them. There are contradictions to his position: he placed a lot of hopes in ‘post colonial’ states and to assist other oppressed people including in the colonial centre. This led Malcolm X to ask these states, especially in Africa, to support the struggles of Black people in the USA. No state in the world has consistently done this, with perhaps the Libyan socialist Jamahirya coming closest to such a role despite its own limitations and contradictions. On the one hand in the struggle against colonialism there is a class that is willing to compromise and turn comprador of one kind or another, and then there is the struggle of the most oppressed who do not want to give up until the colonial enemy and its links to the land are totally severed. This more militant global alliance. This alliance has been whittled away by the imperialist and its agents, its most recent examples are the defeats and disbandment of the peasant guerillas in Colombia, the colonial defeat of the Fenian struggle, and the destruction of Lebanese Hizbullah. In his time, Malcolm X leaned into this radical global alliance against the ‘uncle tom’ dynamic. Malcolm X kept returning to the same theme throughout his political life, that it is the militant struggle of the most oppressed that can ‘win back the land’ in a ‘bloody revolution’ and against the sell-out and the ‘uncle tom’.

The Mau Mau of the Kikuyu peoples in Kenya were perhaps one of the most demonised liberation movements by the West, and especially Britain the coloniser of Kenya. An interviewer asked Malcolm about them saying they are ‘terrorists’, he retorted that it was the conditions of colonial oppression that brought about the righteous Mau Mau resistance. Malcolm X’s position on the Mau Mau was elaborated in his February 15 1965 speech, again just days before his martyrdom: “Don’t you ever be ashamed of the Mau Mau. They’re not to be ashamed of. They are to be proud of. Those brothers were freedom fighters. Not only brothers, there were sisters over there. I met a lot of them. They’re brave … In fact, if they were over here, they’d get this problem straightened up just like that.”

Today we see global racist forces of the ‘new emerging’ powers in the continuing Great Game penetrate more deeply into the global south communities including Africa. We have a series of right-wing, anti-migrant racist (anti-Fulani, anti-Tuareg amongst others) of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger replacing the French colonisers for the Russian, but the decades-long dirty war against African communities is a choice that these regimes are enacting, this time the senior colonial partner is Russia helping to do the massacring and looting. Malcolm X saw Moscow in his time as just another global white power using and abusing the oppressed, indeed Moscow was deeply embedded in British colonialism in India in asking the Indians to unite with their genocidal coloniser during the Second World War, and Stalin formally told Brits to keep their empire (Stalin – Harry Pollitt secret correspondence / British Road to Socialism document).

Malcolm X was inspired by Mao and China. Malcolm X must have witnessed how his comrade Robert F Williams (for whom he raised money and guns in William’s confrontation with the colonialists in North Carolina) was welcomed by Mao in 1963, leading Mao to make a statement in support of their struggle in the USA, being the first head of state to make such a statement. Malcolm X then saw China as part of the global Black Revolution, and he centrally saw promise in that they were severe with the collaborator-class: “The Chinese Revolution—they wanted land. They threw the British out, along with the Uncle Tom Chinese. Yes, they did. They set a good example … When they had the revolution over there, they took a whole generation of Uncle Toms and just wiped them out. And within ten years that little girl became a full-grown woman. No more Toms in China. And today it’s one of the toughest, roughest, most feared countries on this earth—by the white man. Because there are no Uncle Toms over there.” (Message to the Grassroots)

What would have Malcolm made of Mao refusing to meet Black Panther Party leader Huey Newton in Beijing in 1971 because he was prioritising a new alliance with Nixon and Henry Kissinger, the latter to which Beijing was closely aligned until Kissinger’s recent death? Would Malcolm have just annulled all his core positions he espoused to then endorse capitalist behaviour that sought to strategically ally with the colonialist? The truth is Malcolm X was very clear on all these issues, and no matter how our era and people in it are committed to ignoring or twisting Malcolm X on these issues, the man’s entire life cuts through all that and the revolutionary fire burns-on: “You can’t operate a capitalistic system unless you are vulturistic; you have to have someone else’s blood to suck to be a capitalist. You show me a capitalist, I’ll show you a bloodsucker. He cannot be anything but a bloodsucker if he’s going to be a capitalist. He’s got to get it from somewhere other than himself, and that’s where he gets it–from somewhere or someone other than himself. So, when we look at the African continent, when we look at the trouble that’s going on between East and West, we find that the nations in Africa are developing socialistic systems to solve their problems.” (December, 1964)

From socialistic systems of yesteryear to the seeming hype today over right-wing racist military dictatorships who are engaged in the massacres of entire African communities so they and Moscow can benefit, just as Malcolm X said, like bloodscukers. Does the oppressed peoples struggle that unites and empower exist today? The struggle of the oppressed youth against a leading colonial state in Africa – Kenya, is a beautiful one that speaks to Malcolm’s legacy. The struggle of the Punjabi farmers is another. Centrally the Palestinian resistance, which Malcolm X explicitly supported, is another struggle in-line with his politics. However, we are now further and further away from the kind of unity in militant struggle that Malcolm X dedicated his life to.

Malcolm X’s Black Revolution Shines-on, despite the global sellout to racism

Returning to the speeches and interviews of Malcolm X one hundred years since his birth is an opportunity to remind ourselves of our basic shared frameworks, principles and modus operandi if we are opponents of racism and colonialism. If we are in the service of somehow attempting to re-fashion new racism and the new fascist revolution of both ‘west’ and ‘east’ as something ‘good’, then people will and do ignore Malcolm X who stood against such a sell-out. Or at the very least they distort and manipulate and cherry-pick so that their abused version of Malcolm becomes toothless and useless to the oppressed. On all the leading questions of today, Malcolm X was in his lifetime generally, militantly and clearly on the correct side when it comes to the global oppressed and their relationship to white supremacy and colonialism.

If one wants to understand how to unite the oppressed and push against the racism and divisions today, returning to Malcolm is a useful and inspiring tool in those challenges that we face. If we seek resistance and liberation of global south communities, then Malcolm X’s framing of the global struggle in his day is a good way to push-away the growing toxic confusions of today and go back, Sankofa-style, to something that assists in liberation rather re-enslavement back into the colonial word order. Those who stood like Malcolm X did, and those who picked up whatever they could to get at the colonial occupier and free the land and people paid the ultimate price (and most of them their names aren’t recorded anywhere), those who aren’t committed to sell-out are instead committed to these revolutionary martyrs and ancestors who, like Malcolm X, are still speaking to us, still encouraging us: never backwards, but forward.

Sources

Marika Sherwood’s 2011 book, Malcolm X’s Visits Abroad

Bob Brown’s February 2022 interview on Black Power: https://youtu.be/DQgMUW0P8uA?

Malcolm X: Message to the Grassroots, Nov 10 1963: https://www.blackpast.org/

The post Malcolm X at 100 Years appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.