Image by Getty and Unsplash+.

Underground films, transvestites, hippies and freaks, businessmen and secretaries checking out the other side of life, plastic people and people wearing plastic clothes. Smoking the pin joints of Colombian weed sold illegally by a brother hanging on the corner. Go ahead and blush middle America, just don’t call the cops on the party. The Lower East Side loves you and so does the Village. The streets belong to the people and the people belong in the streets; and the theaters and bars, the Factory and its knockoffs. Why be normal? Harry Smith, Bob Dylan, Andy Warhol, Velvet Underground, Jack Smith, Sun Ra, Amiri Baraka, Jonas Mekas, Lenny Bruce, Peter Schumann, Albert Ayler….you get the picture, I hope.

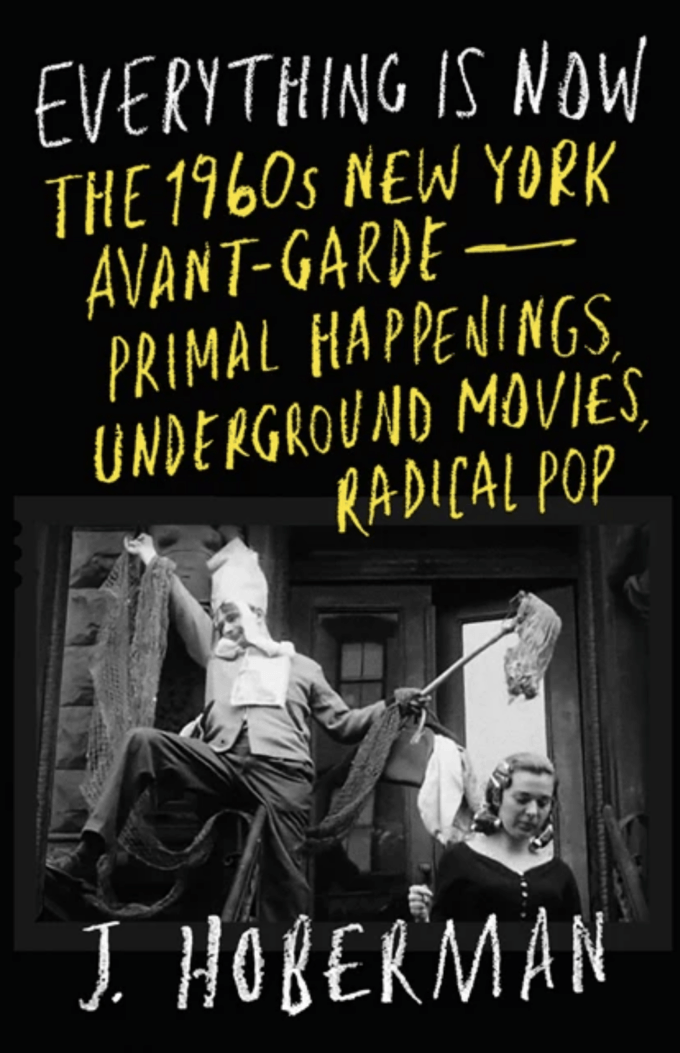

J. Hoberman wrote for the Village Voice for over three decades. His criticism described and detailed the underground and unknown subcultures of the city of Manhattan, revealing a wonderland of the weird, the wonderful and the wishful; he was a critic, observer and even a participant and his columns in the Voice were not to be missed. As a teenager living far from New York City I looked forward to the weekly appearance of the Voice in my local bookstore which, for me was part of the Post Exchange on a US military installation in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Hoberman’s column was but one reason, but it remains a memorable one. His recently published history of the period briefly described in the first paragraph, titled Everything Is Now:The 1960s New York Avant-Garde—Primal Happenings, Underground Movies, Radical Pop, provides the interested public with a lively, occasionally frenetic account of those times.

Hoberman doesn’t write about your ordinary pop culture. Instead, he writes about films made by and featuring sexual outlaws and literary bandits, rock and jazz wild men in tune to the sounds of the street, the soul, and the galaxy, playwrights, actors, and directors whose vision is as warped as the stories they reveal on stage and inside your mind. Sometimes the scenarios he describes are outrageously profound; other times they are just outrageous. The Living Theatre and its founders Julian Beck and Judith Molina are a big part of Hoberman’s history; so is the filmmaker Jack Smith, whose avant-garde films freaked out the mainstream and broke new ground in film. Peter and Elke Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre moved the avant-garde into overtly anti-authoritarian territory. It was a place where this cultural movement existed by definition, but the ever-increasing bloodshed of the US war on the Vietnamese meant someone or something needed to make it explicit. It wasn’t enough to merely live and perform outside the law; one had to create out there, too. The authorities knew this and responded like authorities and their enforcers do: they busted people—filmmakers, actors, audiences, musicians and many others. The litany of censorship arrests listed here and there in the text reminds the reader that the struggle between artistic and literary freedom and the church and the cops is not new and never over. There are always those who want everyone’s mind to be as small as theirs.

Hoberman juxtaposes artists and their creations in a manner that makes the reader reconsider the art and the artists. After introducing jazz artist Ornette Coleman and describing his first record, a recording of a Town Hall concert titled Town Hall (Town Hall 1962), he quotes critic A.B. Spellman, who asks why “other jazzmen concerned with enlarging their forms did not stop and reevaluate their music.”’(101) Hoberman’s next sentence tells the reader that the same question would be raised two years later by Bob Dylan—who went “electric” at that time. Perhaps a hundred pages later, Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde is introduced and discussed in terms of his tangential relationship to Andy Warhol’s Factory, Dylan’s fling (or whatever it was) with Warhol star Edie Sedgwick, the thin, mercury sound of the record and Dylan’s unique, beyond psychedelic take on New York City, where “the all night girls they whisper of escapades out on the “D” train….”

It was a fantastic time when fantasy defied reality, transcending it on the Lower East Side, the Village, and in the minds of thousands, if not millions. The weird became weirder and the weirdos became, if not the majority, a sizeable enough segment of the population to change the culture and the western world. This phenomenon was present in the politics, where the Yippies, Motherfuckers and god knows who else, politicized art by attacking its credentialed philanthropists whose money prevented art from addressing the real issue—war, racism, sexism and the lot. As for mainstream politics, well let me just say, Norman Mailer ran for mayor with Jimmy Breslin as his running mate. John Lindsay was a liberal Republican and the flags officially went to half-mast on Vietnam Moratorium Day in October 1969. The Village Voice seemed almost establishment when compared to the underground newpapers, the East Village Other and The Rat.

The time period covered in Everything is Now was a time of intensifying madness, a period when everything old was challenged and subject to being rendered and burned to ashes. It began as a man’s world, yet by 1971 women were publishing manifestos, taking over The Rat and antagonizing the Met. Gays no longer hid within their unofficially assigned corners and the counterculture dominated the conversation, the street and southern Manhattan. It was from there, San Francisco, London and Los Angeles that the world learned a new way of understanding itself. Art was more than painting, more than film, more than sculpting, and more than music. It became a life force and a way of life for millions. Hoberman’s text describes this time from the heart of the galaxy, the center of the whirlwind. Sometimes manic as the city itself, and never soporific, Everything Is Now cries out for a renaissance of an underground art and underground artists. It yearns for a culture born of art, not profit; an art and music that are obscene and beautiful, relevant and revolutionary, boisterous and contemplative, and never subservient to profiteers and fascists, whether techno or old school.

The post Putting the Avant in Avant-Garde, New York in the Long Sixties appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

This post was originally published on CounterPunch.org.