The U.S. Marshals always get their kill shot — and a young man, young woman, and two five-year-old children swarmed by SOG, special operations group/gang, in Michigan, and the man bleeds out, the kids are in the house traumatized, and the mother is swarmed in the town getting groceries.

I expected to get deep into this Oregon organization’s amazing work, Freedom Farms, working with released inmates to heal, to get back into just plain normal breathing health, working the land, crops, harvests.

Lindsey McNab I met in Ashland, at a farmer’s market, May 2025, and it was just by chance I was there and headed over to the market. Sean was there as well as Lindsey.

This shit works, plying skin to earth, feeding seeds and seedlings, watching lettuce, asparagus, bok choy, potatoes, et al, grow. Yoga and listening circles, sun, rain, moles, dogs, chickens … Care Goddamn People.

Go see the images here at their website: Through the Lens of Giving: Freedom Farms in Pictures

Now, I prepped today’s hour interview by reading a story or two on Freedom Farms and Lindsey: KTVZ21

Participants like Lindsey McNab are proof of the program’s impact. Just six months ago, McNab was behind bars. Now, she spends her days tending to bok choy, turnips, and asparagus, work that she says is helping her find a new sense of purpose.

“I do struggle on a daily basis with[thinking] ‘oh my gosh, I lost 16 months, Like, what do I need to do to make up for that?’ And there isn’t really anything I can do.” McNab said. “Working in a setting like this and this type of work in general forces you and teaches you to be more present.”

McNab said her time in prison offered few moments of peace or even daylight.

“The jail where I was at, we didn’t really even get to see outside. There were no windows and things,” she said. “So that in and of itself creates a lot of emotional, mental anxiety and stress.”

She did get reintroduced to farming through a prison garden program, a rare but meaningful opportunity that helped her cope.

Upon release, she found Freedom Farms, a sanctuary for former inmates ready to rebuild their lives.

*****

But the reality of the Gestapo Criminal injustice system hit us early into the interview for my weekly radio show, Finding Fringe, to air July 2, KYAQ.org, 6 pm PST:

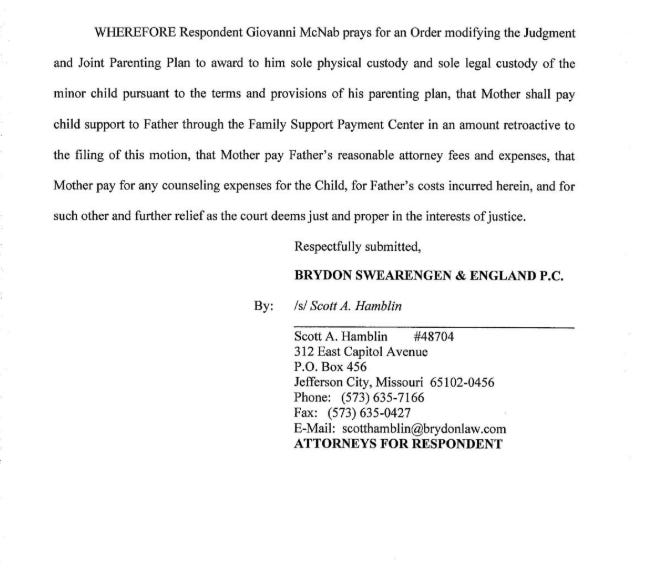

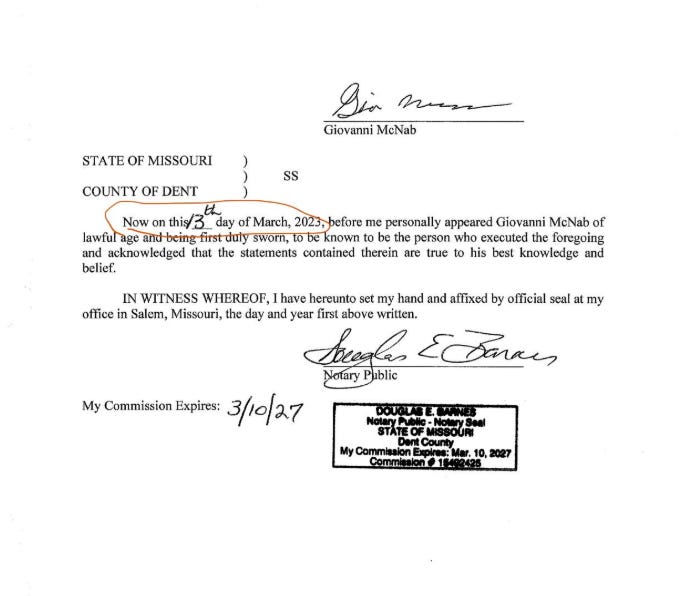

A story about Giovanni and his daughter.

Google the story, with Giovanni McNab and Lindsey and Michigan, and you get the warped story of the cops, the deputies, the overreach that ended up in the death of the young father Giovanni while his two children were inside the cabin as he bled out from a chest wound from a SWAT snipe weapon.

Lindsey was off the property getting groceries, and she was swarmed by U.S. Marshals and their cadre of police. She had no idea there were warrants out for their arrest, and alas, she had no idea what was happening to her two children and her husband.

Here, from Jacob, Giovanni’s brother: August 10, 2023. Jacob McNab:

Giovanni McNab was a hero. He died last night protecting his daughter Hanna Joy McNab. He stood up against insurmountable odds, probably knowing full well that he would not come out of it alive. I am glad no law enforcement lost their lives in the standoff, they were just doing their duty. But my brother was doing his duty, the most sacred duty — a father protecting his child.

This is what Hanna told my brother, Gio, and his new wife Lindsey McNab. Hanna’s mother, Natalie Jones, and her boyfriend, Cory Lutzen (a convicted felon for abuse of an 18-month baby) physically, emotionally, mentally, and sexually abused Hanna. This was recurring abuse. Hanna’s forensic interview is currently on file at Kid’s Harbor but its release has been blocked by law enforcement because it may “endanger the child”… My brother did everything right by going through our country’s legal system, but the system in Missouri must work differently than other places. The most damning evidence to protect my niece, and my family were blocked by the judge. He was treated with hostility by all those who were supposed to protect children.

When he refused to give her up to her abusers, a federal parental kidnapping charge was placed on him and his wife, Lindsey.

Lindsey was arrested when she was out, probably getting groceries. Gio was killed in a standoff with police where a marshal was also injured but is in stable condition.

Hanna is currently being given back to the very people she herself named as her abusers.

I beg someone if you can do anything, please help me get custody of her. If you ask anyone about me, they will vouch for my character and that I will give her the love and care she needs. My wife and I will be able to provide her security and a future. Please don’t let my brother die in vain.

Please follow and share our page Save Hanna McNab.

Here’s my interview June 4, 2025 of Lindsey. Hold onto your emotional seats. KYAQ.org will air it July 2, Finding Fringe: Voices from the Edge.

Yeah, what would you do, uh, if your baby was raped by your ex-wife’s boyfriend?

Look, listen to the show above. And, yes, this involves a minor, a child (three others), and the widow Lindsey has gone through several circles of hell — the husband’s ex-wife’s choice of boyfriends, the child’s rape by that boyfriend, the entire issue of parenting plans and children held as pawns sometimes. The criminal injustice system, social services, case workers, CASA, and the Kafka-esque levels of paperwork and bureaucratic rape this capitalism unleashes upon us.

Look, listen to the show above. And, yes, this involves a minor, a child (three others), and the widow Lindsey has gone through several circles of hell — the husband’s ex-wife’s choice of boyfriends, the child’s rape by that boyfriend, the entire issue of parenting plans and children held as pawns sometimes. The criminal injustice system, social services, case workers, CASA, and the Kafka-esque levels of paperwork and bureaucratic rape this capitalism unleashes upon us.

Here, a post on the Facebook pages around this case:

Stop leaving your kids with them.

Stop leaving your children with your boyfriends you barely know.

Stop letting your family members you don’t entirely trust watch them because it’s free.

If you have a gut feeling about someone who doesn’t sit right with you when it comes to your child, cut all ties with this person.

If your little one comes to you and says I don’t want to stay with a particular person …. do me a favor and listen to them.

~ Cody Bret

And ALWAYS believe them!! I myself would rather believe them and be wrong, than call them a liar and be wrong.

*****

Here’s one of the family members, a dog, the pigs shot: “This is Rigor. He also died protecting Hanna. Please show him love. My brother did not go to heaven alone.”

Ahh, the Show Me State:

Langston Hughes, Tennessee Williams, T.S. Eliot, Kate Chopin and Maya Angelou also hailed from the “show me” state. Edward Michael Harrington Jr. was an American democratic socialist. As a writer, he was best known as the author of The Other America. He was from the show me state too.

Missouri is filled with great stories – and has been home to many amazing storytellers, past and present. Since most of them have written more than one book, you can spend hours escaping into the worlds they created.

Mark Twain (1835-1910) was born in Florida, Missouri, and grew up in Hannibal. William Faulkner called him “the father of American literature” and he’s been lauded as “the greatest humorist this country has ever produced.” His some 25 books include classics like The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and its sequel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which is often called the Great American Novel.

Laura Ingalls Wilder (1867-1957) was born in Wisconsin but spent her adult life in Mansfield. During the Great Depression, she began penning stories about her pioneering childhood, which became the classic Little House on the Prairie nine-book children’s series and 1970s television show.

T.S. Eliot (1888-1965) was born in St. Louis but moved to England at the age of 25. One of the 20th century’s major poets, he wrote at least 13 books and received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1948. His Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, published in 1939, was adapted by Andrew Lloyd Webber as the basis for the musical, Cats.

Langston Hughes (1901-1967) was raised by his grandmother in Joplin until he was 13. After extensive travel during his adult years, he moved to Washington, D.C. where he published his first book of poetry, The Weary Blues, in 1924. Once he graduated from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, he began writing in earnest, starting with his first novel, Not Without Laughter, which won the Harmon gold medal for literature. He is recognized as a major contributor of the Harlem Renaissance.

Robert Heinlein (1902-1988) was born in Butler. Known as the “dean of science fiction writers”, Heinlein wrote more than 30 books, some of which have been made into TV series and movies, including Stranger in a Strange Land and Starship Troopers. A never-before-published Heinlein novel was released in 2020 – 32 years after his death. The Pursuit of the Pankera was reconstructed from pages of an original manuscript and author’s notes with no additional filler, so the work is entirely his own.

Maya Angelou (1928-2014) was born Marguerite Johnson in St. Louis. A leading literary voice of the Black community, she wrote more than a dozen books of prose and poetry. Her best-selling account of her upbringing in segregated rural Arkansas, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, won critical acclaim in 1970.

George Hodgman (1959-2019) returned to his Missouri roots in Madison and Paris for his highly-praised, best-selling memoir Bettyville. The brutally honest, witty and poignant tale explores the experience of a gay cosmopolitan New Yorker returning to a small town filled with both affectionate and painful memories to care for a mother with dementia.

Alexandra Ivy calls Hannibal home and is perhaps the most prolific writer on our list. The New York Times and USA Today best-selling author, who also writes under the name Deborah Raleigh, has published more than 70 books in a wide variety of genres from paranormal and erotic romance to historical and romantic suspense.

Allen Eskens grew up in central Missouri before moving to Minnesota to earn degrees in journalism and law. He uses his education and 25 years of experience in criminal law to write thrilling crime mysteries. His eight books revolve around the events that occur in a small community as told by four main characters: Joe Talbert, Boady Sanden, Lila Nash and Max Rupert. Esken’s first novel, The Life We Bury, has been published in 26 languages.

Daniel Woodrell lives in the Missouri Ozarks where he has drawn inspiration for six of his nine novels and The Outlaw Album, a collection of 12 short stories. His novel, Winter’s Bone, tells the story of Ree Dolly and her quest to find her absent father in order to protect her two young brothers. Along the way she learns dark family secrets and her own determination. The book was adapted to film in 2010 and won American Film Institute Movie of the Year in 2011.

Jim Butcher is an Independence native who wrote his first book in The Dresden Files series – about a professional wizard named Harry Dresden who works as a private investigator and battles supernatural bad guys in modern-day Chicago – when he was 25. The New York Times best-selling author has written 17 books in the series, as well as a six-book fantasy series, Codex Alera.

Gillian Flynn is a Kansas City native with three novels to her credit – Sharp Objects, Dark Places, Gone Girl, and The Grownup – all of which have been adapted for film or television, plus The Grownup, an Edgar Award-winning homage to the classic ghost story. She was nominated for the Golden Globe, Writers Guild of America Award and BAFTA Award for Best Adapted Screenplay for Gone Girl.

Shayne Silvers writes supernatural thrillers – prolifically – from his home in Ozark. He has three separate intertwined series of books featuring Nate Temple, a wizard trying to protect St. Louis from monsters, myths and legends … Callie Penrose, a female spell-slinger in Kansas City … and Quinn MacKenna, a black arms dealer in Boston. The book count in his “Templeverse” stands at 40, and he has also authored a separate three-book vampire series.

Nearly one in five people in U.S. prisons—over 260,000 people—had already served at least 10 years as of 2019. This is an increase from 133,000 people in 2000—which represented 10% of the prison population in that year.

Go here and see just how corrupt and rudimentary the vindictiveness is in our criminal injustice system is:

Okay, you get the picture.

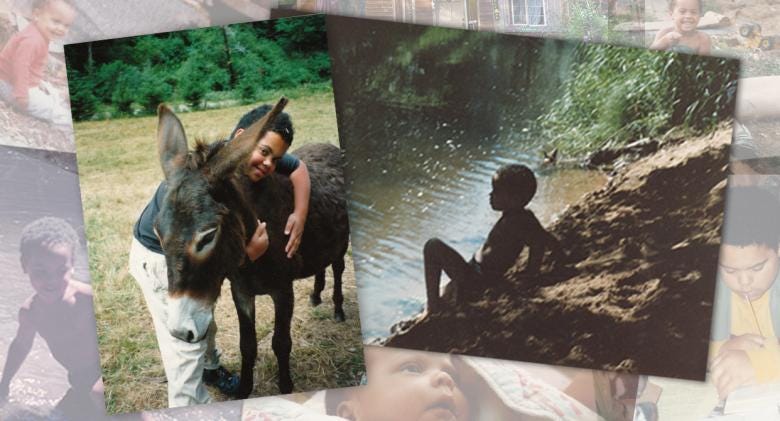

In the 1980s, Jordan Merrell often played in the wilderness near his home, located in the Siuslaw Forest in Lincoln County. Jordan was adopted by Carol Van Strum and husband Paul Merrell when he was days old in 1979. (Photos courtesy of Carol van Strum)

A letter a day for 15 years and 9 months

FINDING FRINGE | A mother’s love reaches into the bowels of the Oregon penal system to keep her son afloat

by Paul K. Haeder | 26 Aug 2020

I catch her in the early evening. Two black bears cross the road just before turning onto her driveway.

It’s light out, but I swear I saw two barn owls swooping into a stand of apple trees.

After I am finished with the interview, she will hold court under the stars with her two Sicilian donkeys, an old mare, a cockatiel, and Amazonian and Patagonia parrots as company. A black Lab mix, Mike, is the outdoor shadow, her sentinel.

A single-barrel 12-gauge shotgun is “just in case.”

I’m on her 20 acres about 30 miles by road from Waldport. The stories Carol Van Strum unfolds are a dervish through many labyrinths. She has been in the Siuslaw Forest for 46 years, but her origins start in 1940, at the dawn of World War II. Her roots were first set down in Port Chester in Westchester County, N.Y., with a father who went to Cornell and a mother who supported the whims and avocations of their five daughters.

At age 79, she’s spry enough to live in an old garage converted into a great room with a bedroom loft. Her cherub cheeks belie an Irish heritage.

I got to know Carol Van Strum a year ago when I was researching her life and her own research on deadly chemicals for another piece — about her fight against the chemical purveyors who sell their brew of toxins to cities, counties, and industries like the timber barons.

Carol’s raison d’etre is the nonfiction gem “A Bitter Fog: Herbicides and Human Rights,” written in 1983, which follows the case of Carol; her husband, Steve; four children (all of whom perished in a suspicious fire in their cabin); neighbors; residents of Lincoln County; and their battle with the state of Oregon, chemical companies, the EPA and the U.S. Forest Service.

The mother

In the verdant wonder of the old homestead, we are about to crack open a pitiful story that turns into triumph.

The miscarriage of justice has to do with race, those without money getting the proverbial short shrift, and a punishment and retributive system of criminal injustice that wants a piece of flesh of every targeted human being.

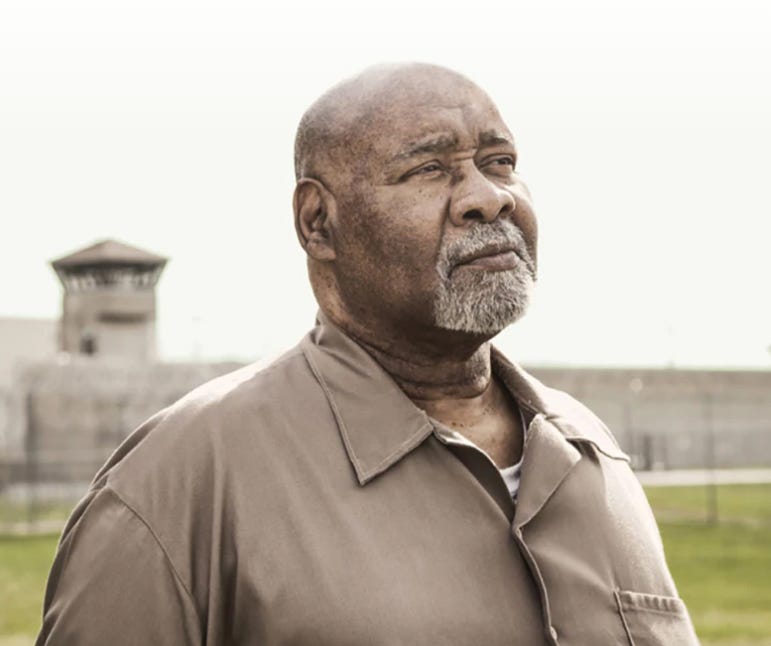

Photo of Jordan courtesy of Carol van Strum. Photo of Carol by Paul K. Haeder.

I am here to drill down into Jordan Merrell’s figurative hell after being wrongly prosecuted and convicted of first-degree murder with a 25-to-life sentence under Oregon’s infamous Measure 11 mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines. That was 1995.

Carol and a second husband, Paul Merrell, adopted Jordan when he was days old in 1979.

“It was a doctor’s friend who had a friend who was a midwife who said she had an African American baby boy who would find it hard to be adopted. His biological mother did not want the baby.”

The young Jordan lived an amazing life with animals, under the big sky of the Central Oregon Coast Range, while communing with fruit trees and adventures splashing in streams while studying newts and chasing crazy barn owls. He played baseball and basketball at Waldport High School, one of two Black students at the school.

The son

It turns out one of the girls had already attempted murdering her grandfather for money, but her juvenile record was sealed and denied as evidence in Jordan’s trial. His court-appointed defense attorney never called three witnesses who would have placed Jordan 3.8 miles away from the murder.

Jordan’s juvenile years were striated in Oregon’s MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility, and when he turned 18, his life transitioned into a veritable crisscrossing of cycling in and out of all of Oregon’s prisons.

Through the hellish trial, then the early days of anger tied to wrongful incarceration, transitioning into years surviving by grit and wits, and finally graduating to learn how to mete out an existence in a dangerous world, Jordan still lands back on the power of his mother keeping him centered.

He explains that Carol is his guardian angel. “Literally, she wrote me a letter every single day. If that’s not dedication, I don’t know what is,” he said.

Jordan’s stick-to-it-ness comes from his school of hard knocks and Carol’s perseverance, as well as this undying dedication to construct a lifeline of letters, books and visits.

“You know, when he went to his first adult prison, there were three Black men who took Jordan under their protection. These men showed him the ropes and protected him. Jordan was a pretty naïve and unworldly kid when he was arrested,” Carol tells me.

The rotten aspect of Jordan’s ordeal is tied to a broken legal system of bad cops, duplicitous district attorneys, incompetent defense lawyers and mean-as-cuss judges. Add to those many strikes against the teenage Draconian constraints of legislation like Measure 11.

“I didn’t have a defense really. He was a low-level lawyer,” Jordan said. “The way the legal system works is that it gets you into a corner and forces you to make a plea bargain.” At the first trial in Lane County, Jordan did not enter a plea agreement. “I didn’t know much then. The attorney tried to step down during my defense.”

The crisscrossing of incarceration blues started with Oregon Corrections’ intake center, then McLaren Youth Correctional Facility, then Oregon State Penitentiary.

In 2008, he won an appeal based on evidence of reasonable doubt — and because the attorney in the initial trial did not call witnesses.

“In this case we found that the defendant did not have effective counsel,” said Stephanie Soden, a spokesperson for the Department of Justice, at the time. “It’s a fairly common reason to petition for post-conviction relief, but it’s one that’s rarely granted.”

He got a new plea deal outside of Measure 11 minimums, and the sentence was reduced, with credit for time served. He tells me he did not think he could convince a new jury of his innocence.

“I assure you I didn’t do what I confessed,” he wrote in a letter to his mother. “But it’s time to move on.”

After his resentencing, he ended up in Lane County jail. More moves to Umatilla County Correctional Facility, Deer Ridge Correctional Institution in Madras, and then Pendleton to Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution, and his last stop was Columbia River Correctional Institution.

He wrote essays during his time inside the wire, and this is from one he wrote when he was “fresh out:”

I walked quickly down the access road that led to the prison — as though the guards might change their minds and chase me down. The immediate area was semi-rural, the access road leading to a small highway that meandered ten blocks or so onto a main boulevard running north and south through much of the city. … I walked for miles through the outskirts of the city, stopping at numerous small stores, none of which accepted my debit card.

Finally, I came to a gas station where the clerk informed me that not only could I not get change from the card, there were no pay phones for miles! This was my first experience of the kindness I had forgotten humans naturally have an instinct for. The clerk let me use his cell phone to call a friend, and when I couldn’t operate it (it appeared to have no buttons — I thought about trying to give it a voice command) he dialed it for me.

“Early on I was angry, but when I got out, I was euphoric,” Jordan tells me. He ended up at a community house in Multnomah County — run by Phoenix Rising Transitions.

He emphasizes being around other guys just like him who understood his way of thinking was powerful. Learning new responsibilities at the house helped Jordan during the four months of halfway house living.

“It was a good way of transitioning, as opposed to ending up in a studio apartment by myself. Outside, people were rude and disrespectful, so having guys from prison on the same page made it easier since we understood where we had come from and understood our way of thinking,” he said.

Jordan was halfway through the ninth grade when he was incarcerated. He knows how tough it is in prison finding role models.

“While inside, I focused on change. I had to create an imaginary role model. It all comes down to being logical about things — is doing A going to get me to B and so on.”

When he was released, on a few occasions Jordan ran into fellow inmates who still stayed “involved in all the illegal stuff. They hung onto what they did that got them to prison in the first place.”

His best friend (one of only a few friends) is back in prison because of this arrested development.

Stepping stones inside and outside the wire

I ask Jordan what he aspired to be in his formative years.

“I guess I wanted to be a cop,” he said chuckling. He ended up out of prison working on a degree in accounting, married and with a 10-year-old stepdaughter.

His life moved quickly in some regards once outside the wire — he met Julie three weeks after leaving prison. Then three weeks later they were married. They have been a couple since 2013.

Both Carol and Jordan tell me Julie is a smart woman who’s organized and into logistics. Jordan said they both had aspirations of doing a catering service — a mobile pub or bar. The pandemic has put all those ideas on hold. He’s at Mt. Hood Community College taking classes for an associate degree. He’s also out on parole for life. While he doesn’t report in person anymore, he’s still charged a $35 per month supervision fee.

He continually reminds me of evolution, transformation and transmogrification now that he has family and purpose.

“I have left that part of my life behind. I am now doing something specifically focused on getting my life together and being devoted to my family. I lost almost 16 years of my life. I had no job experience, no life experience (outside of prison), no education.”

He mentions this after I prod him about why he’s not writing more, maybe even penning a memoir.

Jordan admits it’s possible a book might come later. “Before, when I was writing, I was in a cell for 23 or more hours a day. I had nothing else to do, so I could focus on the writing. Maybe later when I am more established.”

Overt racism Jordan endured in high school, Carol relays, was both ugly and absurd. “The only Black kid at Waldport High School. He was pulled out of class by the principal and was accused of being a gang member. How absurd — a gang of one.”

Much of Carol’s novel, “Oreo File,” is patterned after a young boy like Jordan.

While looking at her heritage corn stalks, I am gifted several books by Carol, including “Cross Country ABC: 1957,” which is an account of the trip she and two sisters took across the U.S. in a 1956 Chevy station wagon.

Then another book, penned in 2009, “The Story of a Barn – Alder Hill.” The barn was on her property, built in 1930 by Elihu Buck, an engineer who had worked on the Gold State Bridge. This gem of a short book is a history of the property, the surrounding homesteads, the trees, the creamery in Waldport as well as the Red Octopus Theatre performances premiering in the barn.

This is part and parcel of Jordan’s history, too, as he knows the land and knows the place. It’s tied up in his spiritual and cultural DNA. The book written by Carol as a tribute to Jordan is another gem – “Northern Spy: A Good Apple Tree.” The book is like a narrative poem about Jordan’s life here, from adopted baby to child to teenager.

On the hillside by the house is a grand old apple tree called Northern Spy. It was planted at the birth of a beautiful child.

Then, later:

Far away behind steel and concrete, the boy grew into a man. His faithful dog Sherlock died without seeing him again.

Then, at the end of the book, Jordan is a 33-year-old man, with his wife, Julie:

There would be difficult times ahead, looking for work, finding a place to live, enrolling in college. But good times awaited, too. By summer there would be someone to share both happy times and tough ones. Someone to take home at last and show where he came from.

The post Listening to a Mother’s Horror with US Marshals: Perpetual Vicarious Trauma first appeared on Dissident Voice.“That’s my redwood,” he would say. “I planted it. And see beyond it, that’s my apple tree.”

He would show her the river, the donkey, the gardens, the flowers, an iguana’s grave.

And come fall there would be buckets of apples from his beloved Northern Spy.

This post was originally published on Dissident Voice.