The regulation of ultra-processed foods has been the talk of US food policy ever since Robert F Kennedy Jr took office – the FDA will soon weigh in.

The conversation surrounding ultra-processed foods (UPFs) in the US is about to be taken up a notch, with the country’s food regulator reportedly looking to create a definition for such products.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is hoping that its description would encourage companies to label their offerings as ‘non-ultra-processed’ the same way products are marketed as sugar- or fat-free.

“We do not see ultra-processed foods as foods to be banned. We see them as foods to be defined so that markets can compete based on health,” FDA commissioner Marty Makary told the New York Times.

The move could have wide-ranging implications for food policy, manufacturing, and purchases, and aligns with health secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr’s Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) mandate, with a recent government report putting the spotlight on UPFs and their link to chronic illness in children.

Why the FDA is working on a UPF definition

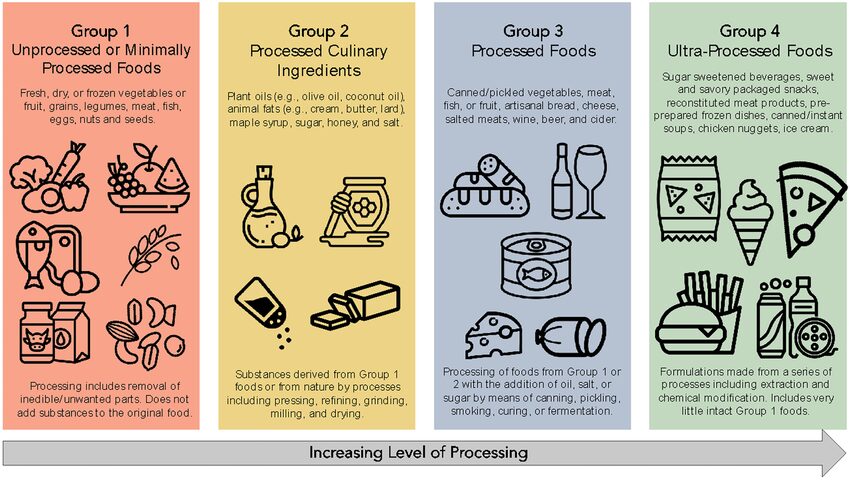

As a category, UPFs were born out of the Nova classification established by scientists at the University of São Paulo in 2009. They defined ultra-processed products as those made from industrial formulations and techniques like extrusion or pre-frying, and cosmetic substances such as high-fructose corn syrup and hydrogenated oils.

In simple terms, they’re foods you likely won’t be able to make at home. The definition itself is broad – too much so, some experts argue. So while a packet of Lay’s, a can of Pepsi, and a protein bar could be a UPF lunch, so could a plant-based beef burger with some blueberry yoghurt.

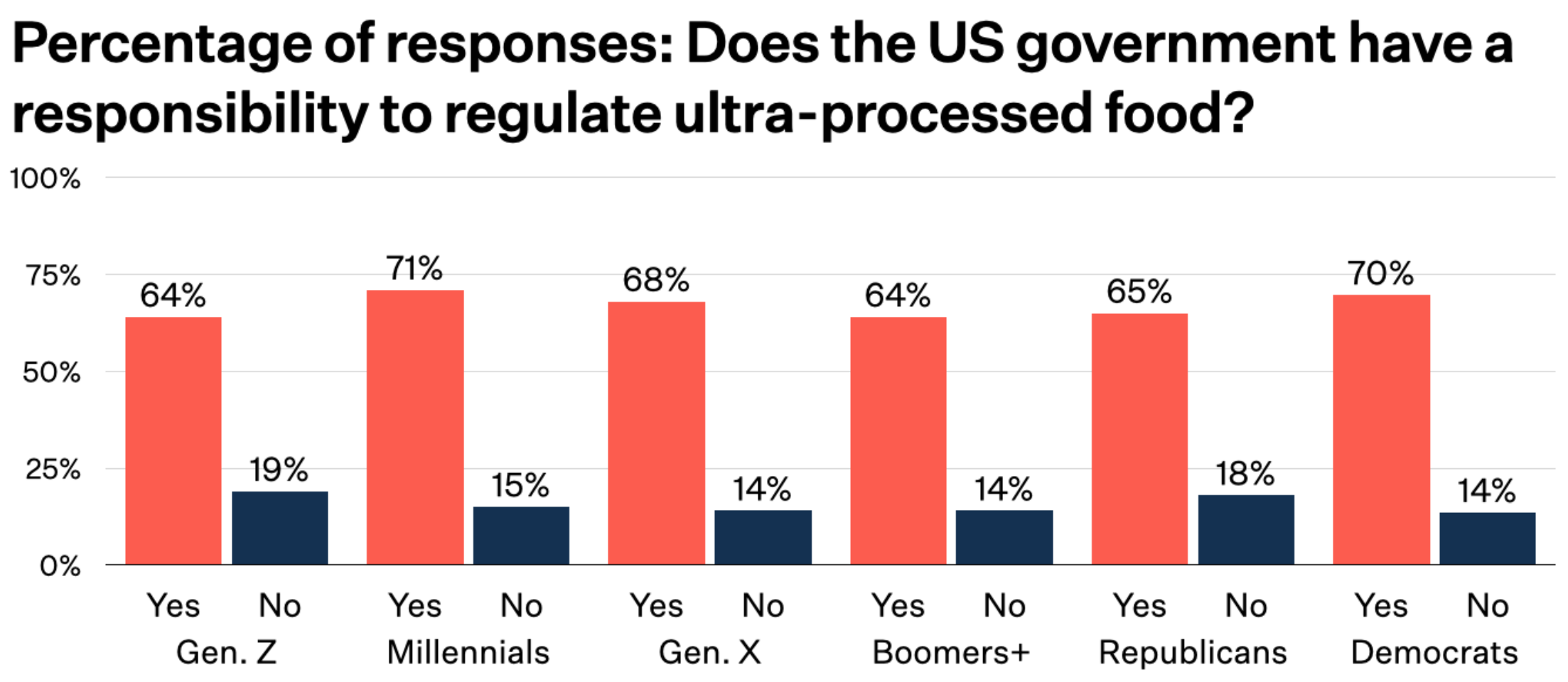

That has, understandably, led to a lot of confusion. A recent survey found that 35% of Americans hadn’t heard of UPFs in 2024, and a third were aware of the term but weren’t sure what it means. Meanwhile, around two-thirds of consumers, spanning all ages and both sides of the aisle, believe the US government has a responsibility to regulate them.

This is because a host of studies have linked UPFs to health conditions like obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and even early death. At the same time, many experts have warned against associating processing with nutrition, suggesting that not every ultra-processed product is bad for you.

For example, whole-grain cereals and supermarket breads contain important nutrients, especially fibre, while plant-based alternatives to meat and milk offer protein with much more fibre and less saturated fat than their animal-derived counterparts. Studies have concluded that these products don’t carry the same health risks as, say, a KitKat bar or a bottle of Mountain Dew, so bundling them all in the same category is misleading.

The FDA’s definition would hope to clear the confusion. It could entail an assessment of the chemicals and additives in foods, the number of ingredients in a product, and the nutritional values. This, the Times suggested, could shape school lunch policy, regulate what foods are available via federal assistance programmes, or be used to recommend a reduction in UPF consumption in the national dietary guidelines.

Scientists advising the government on the latter, due later this year, chose not to include a recommendation on UPFs, citing a lack of evidence. An FDA definition could also see warning labels be added to packaging (something about 70% of Americans support) or banning the advertising of UPFs to children (akin to the upcoming junk food ad ban in the UK).

Children’s health and additives in sharp focus

The FDA is addressing UPFs because they are virtually everywhere in the food system. They comprise 60% of an average American’s daily calories, and 70% of what the country’s children eat.

The focus on children’s health has been magnified over the last year. In Pennsylvania, an 18-year-old has sued 11 major food producers, alleging that they engineered UPFs to be as addictive as cigarettes and marketed them to kids, causing them to develop chronic illnesses.

Meanwhile, the government’s recent MAHA report dedicated an entire section to the impact of UPFs on kids, blaming “decades of policies that have undermined the food system and perpetuated the delivery of unhealthy food to our children”.

It chimes with RFK Jr’s rhetoric on UPFs. Before entering the administration, he had promised to ban the purchase of processed foods through food stamps and vowed to remove UPFs from school lunches.

While states like Arizona and Utah have enacted legislation to define UPFs, these focus mainly on the use of additives. Meanwhile, California Governor Gavin Newsom has directed state departments to explore potential actions that can limit the harms associated with these foods, which could include the use of warning labels on packaging.

Speaking of labels, the FDA itself updated its guidance on what products can be labelled as ‘healthy’ for the first time in nearly three decades. The revised rules plain, low-fat Greek yoghurt and a trail mix count as healthy, but fortified breakfast cereals and white bread no longer do.

The agency’s deputy commissioner of food, Kyle Diamantas, suggested that some of the “obvious areas” it will consider as part of its definition include synthetic dyes, emulsifiers and preservatives.

While the effort is being led by the FDA, it includes other agencies too, such as the Department of Agriculture. Once a definition has been drafted, the government will open it up to public comments before finalising it in the months ahead.

The post US FDA to Develop Definition of Ultra-Processed Foods appeared first on Green Queen.

This post was originally published on Green Queen.